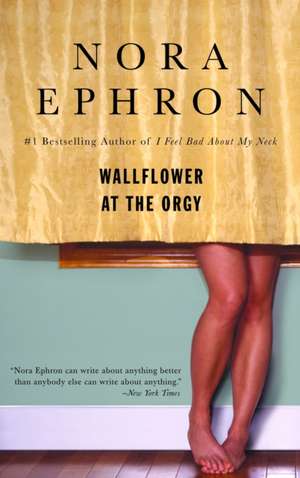

Wallflower at the Orgy

Autor Nora Ephronen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2007

Preț: 113.89 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 171

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.79€ • 22.81$ • 18.03£

21.79€ • 22.81$ • 18.03£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553385052

ISBN-10: 0553385054

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 134 x 207 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553385054

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 134 x 207 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Nora Ephron is also the author of I Feel Bad About My Neck, Crazy Salad, Scribble Scribble, and Heartburn. She received Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay for When Harry Met Sally…, Silkwood, and Sleepless in Seattle, which she also directed. Her other credits include the films Michael, You've Got Mail, and the play Imaginary Friends. She lives in New York City with her husband, writer Nicholas Pileggi.

Extras

The Food

Establishment:

Life in the Land of the Rising Souffle

(Or Is It the Rising Meringue?)

One day, I awoke having had my first in a long series of food anxiety dreams (the way it goes is this: there are eight people coming to dinner in twenty minutes, and I am in an utter panic because I have forgotten to buy the food, plan the menu, set the table, clean the house, and the supermarket is closed). I knew that I had become a victim of the dreaded food obsession syndrome and would have to do something about it. This article is what I did.

Incidentally, I anticipated that my interviews on this would be sublime gourmet experiences, with each of my subjects forcing little goodies down my throat. But no. All I got from over twenty interviews were two raw potatoes that were guaranteed by their owner (who kept them in a special burlap bag on her terrace) to be the only potatoes worth eating in all the world. Perhaps they were. I don't know, though; they tasted exactly like the other potatoes I've had in my life.

September 1968

You might have thought they'd have been polite enough not to mention it at all. Or that they'd wait at least until they got through the reception line before starting to discuss it. Or that they'd hold off at least until after they had tasted the food--four tables of it, spread about the four corners of the Four Seasons--and gotten drinks in hand. But people in the Food Establishment are not noted for their manners or their patience, particularly when there is fresh gossip. And none of them had come to the party because of the food.

They had come, most of them, because they were associated with the Time-Life Cookbooks, a massive, high-budget venture that has managed to involve nearly everyone who is anyone in the food world. Julia Child was a consultant on the first book. And James Beard had signed on to another. And Paula Peck, who bakes. And Nika Hazelton, who reviews cookbooks for the New York Times Book Review. And M.F.K. Fisher, usually of The New Yorker. And Waverley Root of Paris, France. And Pierre Franey, the former chef of Le Pavillon who is now head chef at Howard Johnson's. And in charge of it all, Michael Field, the birdlike, bespectacled, frenzied gourmet cook and cookbook writer, who stood in the reception line where everyone was beginning to discuss it. Michael was a wreck. A wreck, a wreck, a wreck, as he himself might have put it. Just that morning, the very morning of the party, Craig Claiborne of the New York Times, who had told the Time-Life people he would not be a consultant for their cookbooks even if they paid him a hundred thousand dollars, had ripped the first Time-Life cookbook to shreds and tatters. Merde alors, as Craig himself might have put it, how that man did rip that book to shreds and tatters. He said that the recipes, which were supposed to represent the best of French provincial cooking, were not even provincial. He said that everyone connected with the venture ought to be ashamed of himself. He was rumored to be going about town telling everyone that the picture of the souffle on the front of the cookbook was not even a souffle--it was a meringue! Merde alors! He attacked Julia Child, the hitherto unknockable. He referred to Field, who runs a cooking school and is author of two cookbooks, merely as a "former piano player." Not that Field wasn't a former piano player. But actually identifying him as one--well! "As far as Craig and I are concerned," Field was saying as the reception line went on, "the gauntlet is down." And worst of all--or at least it seemed worst of all that day--Craig had chosen the day of the party for his review. Poor Michael. How simply frightful! How humiliating! How delightful! "Why did he have to do it today?" moaned Field to Claiborne's close friend, chef Pierre Franey. "Why? Why? Why?"

Why indeed?

The theories ranged from Gothic to Byzantine. Those given to the historical perspective said that Craig had never had much respect for Michael, and they traced the beginnings of the rift back to 1965, when Claiborne had gone to a restaurant Field was running in East Hampton and given it one measly star. Perhaps, said some. But why include Julia in the blast? Craig had done that, came the reply, because he had never liked Michael and wanted to tell Julia to get out of Field's den of thieves. Perhaps, said still others. But mightn't he also have done it because his friend Franey had signed on as a consultant to the Time-Life Cookbook of Haute Cuisine just a few weeks before, and Craig wanted to tell him to get out of that den of thieves? Perhaps, said others. But it might be even more complicated. Perhaps Craig had done it because he was furious at Michael Field's terrible review in the New York Review of Books of Gloria Bley Miller's The Thousand Recipe Chinese Cookbook, which Craig had praised in the Times.

Now, while all this was becoming more and more arcane, there were a few who secretly believed that Craig had done the deed because the Time-Life cookbook was as awful as he thought it was. But most of those people were not in the Food Establishment. Things in the Food Establishment are rarely explained that simply. They are never what they seem. People who seem to be friends are not. People who admire each other call each other Old Lemonface and Cranky Craig behind backs. People who tell you they love Julia Child will add in the next breath that of course her husband is a Republican and her orange Bavarian cream recipe just doesn't work. People who tell you Craig Claiborne is a genius will insist he had little or nothing to do with the New York Times Cookbook, which bears his name. People will tell you that Michael Field is delightful but that some people do not take success quite as well as they might. People who claim that Dione Lucas is the most brilliant food technician of all time further claim that when she puts everything together it comes out tasting bland. People who love Paula Peck will go on to tell you--but let one of them tell you. "I love Paula," one of them is saying, "but no one, absolutely no one understands what it is between Paula and monosodium glutamate."

Bitchy? Gossipy? Devious?

"It's a world of self-generating hysteria," says Nika Hazelton. And those who say the food world is no more ingrown than the theater world and the music world are wrong. The food world is smaller. Much more self-involved. And people in the theater and in music are part of a culture that has been popularly accepted for centuries; people in the food world are riding the crest of a trend that began less than twenty years ago.

In the beginning, just about the time the Food Establishment began to earn money and fight with each other and review each other's books and say nasty things about each other's recipes and feel rotten about each other's good fortune, just about that time, there came curry. Some think it was beef Stroganoff, but in fact, beef Stroganoff had nothing to do with it. It began with curry. Curry with fifteen little condiments and Major Grey's mango chutney. The year of the curry is an elusive one to pinpoint, but this much is clear: it was before the year of quiche Lorraine, the year of paella, the year of vitello tonnato, the year of boeuf Bourguignon, the year of blanquette de veau, and the year of beef Wellington. It was before Michael stopped playing the piano, before Julia opened L'Ecole des Trois Gourmandes, and before Craig had left his job as a bartender in Nyack, New York. It was the beginning, and in the beginning there was James Beard and there was curry and that was about all.

Historical explanations of the rise of the Food Establishment do not usually begin with curry. They begin with the standard background on the gourmet explosion--background that includes the traveling fighting men of World War Two, the postwar travel boom, and the shortage of domestic help, all of which are said to have combined to drive the housewives of America into the kitchen.

This background is well and good, but it leaves out the curry development. In the 1950s, suddenly, no one knew quite why or how, everyone began to serve curry. Dinner parties in fashionable homes featured curried lobster. Dinner parties in middle-income homes featured curried chicken. Dinner parties in frozen-food compartments featured curried rice. And with the arrival of curry, the first fashionable international food, food acquired a chic, a gloss of snobbery it had hitherto possessed only in certain upper-income groups. Hostesses were expected to know that iceberg lettuce was declasse and tunafish casseroles de trop. Lancers sparkling rose and Manischewitz were replaced on the table by Bordeaux. Overnight rumaki had a fling and became a cliche.

The American hostess, content serving frozen spinach for her family, learned to make a spinach souffle for her guests. Publication of cookbooks tripled, quadrupled, quintupled; the first cookbook-of-the-month club, the Cookbook Guild, flourished. At the same time, American industry realized that certain members of the food world--like James Beard, whose name began to have a certain celebrity--could help make foods popular. The French's mustard people turned to Beard. The can-opener people turned to Poppy Cannon. Pan American Airways turned to Myra Waldo. The Potato Council turned to Helen McCully. The Northwest Pear Association and the Poultry and Egg Board and the Bourbon Institute besieged food editors for more recipes containing their products. Cookbook authors were retained, at sizable fees, to think of new ways to cook with bananas. Or scallions. Or peanut butter. "You know," one of them would say, looking up from a dinner made during the peanut-butter period, "it would never have occurred to me to put peanut butter on lamb, but actually, it's rather nice."

Before long, American men and women were cooking along with Julia Child, subscribing to the Shallot-of-the-Month Club, and learning to mince garlic instead of pushing it through a press. Cheeses, herbs, and spices that had formerly been available only in Bloomingdale's delicacy department cropped up around New York, and then around the country. Food became, for dinner-party conversations in the sixties, what abstract expressionism had been in the fifties. And liberated men and women who used to brag that sex was their greatest pleasure began to suspect that food might be pulling ahead in the ultimate taste test.

Generally speaking, the Food Establishment--which is not to be confused with the Restaurant Establishment, the Chef Establishment, the Food-Industry Establishment, the Gourmet Establishment, or the Wine Establishment--consists of those people who write about food or restaurants on a regular basis, either in books, magazines, or certain newspapers, and thus have the power to start trends and, in some cases, begin and end careers. Most of them earn additional money through lecture tours, cooking schools, and consultancies for restaurants and industry. A few appear on radio and television.

The typical member of the Food Establishment lives in Greenwich Village, buys his vegetables at Balducci's, his bread at the Zito bakery, and his cheese at Bloomingdale's. He dines at the Coach House. He is given to telling you, apropos of nothing, how many souffles he has been known to make in a short period of time. He is driven mad by a refrain he hears several times a week: "I'd love to have you for dinner," it goes, "but I'd be afraid to cook for you." He insists that there is no such thing as an original recipe; the important thing, he says, is point of view. He lists as one of his favorite cookbooks the original Joy of Cooking by Irma Rombauer, and adds that he wouldn't be caught dead using the revised edition currently on the market. His cookbook library runs to several hundred volumes. He gossips a good deal about his colleagues, about what they are cooking, writing, and eating, and whom they are talking to; about everything, in fact, except the one thing everyone else in the universe gossips about--who is sleeping with whom. In any case, he claims that he really does not spend much time with other members of the Food Establishment, though he does bump into them occasionally at Sunday lunch at Jim Beard's or at one of the publishing parties he is obligated to attend. His publisher, if he is lucky, is Alfred A. Knopf.

He takes himself and food very very seriously. He has been known to debate for hours such subjects as whether nectarines are peaches or plums, and whether the vegetables that Michael Field, Julia Child, and James Beard had one night at La Caravelle and said were canned were in fact canned. He roundly condemns anyone who writes more than one cookbook a year. He squarely condemns anyone who writes a cookbook containing untested recipes. Colleagues who break the rules and succeed are hailed almost as if they had happened on a new galaxy. "Paula Peck," he will say, in hushed tones of awe, "broke the rules in puff paste." If the Food Establishmentarian makes a breakthrough in cooking methods--no matter how minor and superfluous it may seem--he will celebrate. "I have just made a completely and utterly revolutionary discovery," said Poppy Cannon triumphantly one day. "I have just developed a new way of cooking asparagus."

There are two wings to the Food Establishment, each in mortal combat with the other. On the one side are the revolutionaries--as they like to think of themselves--the home economists and writers and magazine editors who are industry-minded and primarily concerned with the needs of the average housewife. Their virtues are performance, availability of product, and less work for mother; their concern is with improving American food. "There is an awe about Frenchiness in food which is terribly precious and has kept American food from being as good as it could be," says Poppy Cannon, the leader of the revolutionaries. "People think French cooking is gooking it up. All this kowtowing to so-called French food has really been a hindrance rather than a help." The revolutionaries pride themselves on discovering short cuts and developing convenience foods; they justify the compromises they make and the loss of taste that results by insisting that their recipes, while unquestionably not as good as the originals, are probably a good deal better than what the American housewife would prepare if left to her own devices. When revolutionaries get together, they talk about the technical aspects of food: how to ripen a tomato, for example; and whether the extra volume provided by beating eggs with a wire whisk justifies not using the more convenient electric beater.

Establishment:

Life in the Land of the Rising Souffle

(Or Is It the Rising Meringue?)

One day, I awoke having had my first in a long series of food anxiety dreams (the way it goes is this: there are eight people coming to dinner in twenty minutes, and I am in an utter panic because I have forgotten to buy the food, plan the menu, set the table, clean the house, and the supermarket is closed). I knew that I had become a victim of the dreaded food obsession syndrome and would have to do something about it. This article is what I did.

Incidentally, I anticipated that my interviews on this would be sublime gourmet experiences, with each of my subjects forcing little goodies down my throat. But no. All I got from over twenty interviews were two raw potatoes that were guaranteed by their owner (who kept them in a special burlap bag on her terrace) to be the only potatoes worth eating in all the world. Perhaps they were. I don't know, though; they tasted exactly like the other potatoes I've had in my life.

September 1968

You might have thought they'd have been polite enough not to mention it at all. Or that they'd wait at least until they got through the reception line before starting to discuss it. Or that they'd hold off at least until after they had tasted the food--four tables of it, spread about the four corners of the Four Seasons--and gotten drinks in hand. But people in the Food Establishment are not noted for their manners or their patience, particularly when there is fresh gossip. And none of them had come to the party because of the food.

They had come, most of them, because they were associated with the Time-Life Cookbooks, a massive, high-budget venture that has managed to involve nearly everyone who is anyone in the food world. Julia Child was a consultant on the first book. And James Beard had signed on to another. And Paula Peck, who bakes. And Nika Hazelton, who reviews cookbooks for the New York Times Book Review. And M.F.K. Fisher, usually of The New Yorker. And Waverley Root of Paris, France. And Pierre Franey, the former chef of Le Pavillon who is now head chef at Howard Johnson's. And in charge of it all, Michael Field, the birdlike, bespectacled, frenzied gourmet cook and cookbook writer, who stood in the reception line where everyone was beginning to discuss it. Michael was a wreck. A wreck, a wreck, a wreck, as he himself might have put it. Just that morning, the very morning of the party, Craig Claiborne of the New York Times, who had told the Time-Life people he would not be a consultant for their cookbooks even if they paid him a hundred thousand dollars, had ripped the first Time-Life cookbook to shreds and tatters. Merde alors, as Craig himself might have put it, how that man did rip that book to shreds and tatters. He said that the recipes, which were supposed to represent the best of French provincial cooking, were not even provincial. He said that everyone connected with the venture ought to be ashamed of himself. He was rumored to be going about town telling everyone that the picture of the souffle on the front of the cookbook was not even a souffle--it was a meringue! Merde alors! He attacked Julia Child, the hitherto unknockable. He referred to Field, who runs a cooking school and is author of two cookbooks, merely as a "former piano player." Not that Field wasn't a former piano player. But actually identifying him as one--well! "As far as Craig and I are concerned," Field was saying as the reception line went on, "the gauntlet is down." And worst of all--or at least it seemed worst of all that day--Craig had chosen the day of the party for his review. Poor Michael. How simply frightful! How humiliating! How delightful! "Why did he have to do it today?" moaned Field to Claiborne's close friend, chef Pierre Franey. "Why? Why? Why?"

Why indeed?

The theories ranged from Gothic to Byzantine. Those given to the historical perspective said that Craig had never had much respect for Michael, and they traced the beginnings of the rift back to 1965, when Claiborne had gone to a restaurant Field was running in East Hampton and given it one measly star. Perhaps, said some. But why include Julia in the blast? Craig had done that, came the reply, because he had never liked Michael and wanted to tell Julia to get out of Field's den of thieves. Perhaps, said still others. But mightn't he also have done it because his friend Franey had signed on as a consultant to the Time-Life Cookbook of Haute Cuisine just a few weeks before, and Craig wanted to tell him to get out of that den of thieves? Perhaps, said others. But it might be even more complicated. Perhaps Craig had done it because he was furious at Michael Field's terrible review in the New York Review of Books of Gloria Bley Miller's The Thousand Recipe Chinese Cookbook, which Craig had praised in the Times.

Now, while all this was becoming more and more arcane, there were a few who secretly believed that Craig had done the deed because the Time-Life cookbook was as awful as he thought it was. But most of those people were not in the Food Establishment. Things in the Food Establishment are rarely explained that simply. They are never what they seem. People who seem to be friends are not. People who admire each other call each other Old Lemonface and Cranky Craig behind backs. People who tell you they love Julia Child will add in the next breath that of course her husband is a Republican and her orange Bavarian cream recipe just doesn't work. People who tell you Craig Claiborne is a genius will insist he had little or nothing to do with the New York Times Cookbook, which bears his name. People will tell you that Michael Field is delightful but that some people do not take success quite as well as they might. People who claim that Dione Lucas is the most brilliant food technician of all time further claim that when she puts everything together it comes out tasting bland. People who love Paula Peck will go on to tell you--but let one of them tell you. "I love Paula," one of them is saying, "but no one, absolutely no one understands what it is between Paula and monosodium glutamate."

Bitchy? Gossipy? Devious?

"It's a world of self-generating hysteria," says Nika Hazelton. And those who say the food world is no more ingrown than the theater world and the music world are wrong. The food world is smaller. Much more self-involved. And people in the theater and in music are part of a culture that has been popularly accepted for centuries; people in the food world are riding the crest of a trend that began less than twenty years ago.

In the beginning, just about the time the Food Establishment began to earn money and fight with each other and review each other's books and say nasty things about each other's recipes and feel rotten about each other's good fortune, just about that time, there came curry. Some think it was beef Stroganoff, but in fact, beef Stroganoff had nothing to do with it. It began with curry. Curry with fifteen little condiments and Major Grey's mango chutney. The year of the curry is an elusive one to pinpoint, but this much is clear: it was before the year of quiche Lorraine, the year of paella, the year of vitello tonnato, the year of boeuf Bourguignon, the year of blanquette de veau, and the year of beef Wellington. It was before Michael stopped playing the piano, before Julia opened L'Ecole des Trois Gourmandes, and before Craig had left his job as a bartender in Nyack, New York. It was the beginning, and in the beginning there was James Beard and there was curry and that was about all.

Historical explanations of the rise of the Food Establishment do not usually begin with curry. They begin with the standard background on the gourmet explosion--background that includes the traveling fighting men of World War Two, the postwar travel boom, and the shortage of domestic help, all of which are said to have combined to drive the housewives of America into the kitchen.

This background is well and good, but it leaves out the curry development. In the 1950s, suddenly, no one knew quite why or how, everyone began to serve curry. Dinner parties in fashionable homes featured curried lobster. Dinner parties in middle-income homes featured curried chicken. Dinner parties in frozen-food compartments featured curried rice. And with the arrival of curry, the first fashionable international food, food acquired a chic, a gloss of snobbery it had hitherto possessed only in certain upper-income groups. Hostesses were expected to know that iceberg lettuce was declasse and tunafish casseroles de trop. Lancers sparkling rose and Manischewitz were replaced on the table by Bordeaux. Overnight rumaki had a fling and became a cliche.

The American hostess, content serving frozen spinach for her family, learned to make a spinach souffle for her guests. Publication of cookbooks tripled, quadrupled, quintupled; the first cookbook-of-the-month club, the Cookbook Guild, flourished. At the same time, American industry realized that certain members of the food world--like James Beard, whose name began to have a certain celebrity--could help make foods popular. The French's mustard people turned to Beard. The can-opener people turned to Poppy Cannon. Pan American Airways turned to Myra Waldo. The Potato Council turned to Helen McCully. The Northwest Pear Association and the Poultry and Egg Board and the Bourbon Institute besieged food editors for more recipes containing their products. Cookbook authors were retained, at sizable fees, to think of new ways to cook with bananas. Or scallions. Or peanut butter. "You know," one of them would say, looking up from a dinner made during the peanut-butter period, "it would never have occurred to me to put peanut butter on lamb, but actually, it's rather nice."

Before long, American men and women were cooking along with Julia Child, subscribing to the Shallot-of-the-Month Club, and learning to mince garlic instead of pushing it through a press. Cheeses, herbs, and spices that had formerly been available only in Bloomingdale's delicacy department cropped up around New York, and then around the country. Food became, for dinner-party conversations in the sixties, what abstract expressionism had been in the fifties. And liberated men and women who used to brag that sex was their greatest pleasure began to suspect that food might be pulling ahead in the ultimate taste test.

Generally speaking, the Food Establishment--which is not to be confused with the Restaurant Establishment, the Chef Establishment, the Food-Industry Establishment, the Gourmet Establishment, or the Wine Establishment--consists of those people who write about food or restaurants on a regular basis, either in books, magazines, or certain newspapers, and thus have the power to start trends and, in some cases, begin and end careers. Most of them earn additional money through lecture tours, cooking schools, and consultancies for restaurants and industry. A few appear on radio and television.

The typical member of the Food Establishment lives in Greenwich Village, buys his vegetables at Balducci's, his bread at the Zito bakery, and his cheese at Bloomingdale's. He dines at the Coach House. He is given to telling you, apropos of nothing, how many souffles he has been known to make in a short period of time. He is driven mad by a refrain he hears several times a week: "I'd love to have you for dinner," it goes, "but I'd be afraid to cook for you." He insists that there is no such thing as an original recipe; the important thing, he says, is point of view. He lists as one of his favorite cookbooks the original Joy of Cooking by Irma Rombauer, and adds that he wouldn't be caught dead using the revised edition currently on the market. His cookbook library runs to several hundred volumes. He gossips a good deal about his colleagues, about what they are cooking, writing, and eating, and whom they are talking to; about everything, in fact, except the one thing everyone else in the universe gossips about--who is sleeping with whom. In any case, he claims that he really does not spend much time with other members of the Food Establishment, though he does bump into them occasionally at Sunday lunch at Jim Beard's or at one of the publishing parties he is obligated to attend. His publisher, if he is lucky, is Alfred A. Knopf.

He takes himself and food very very seriously. He has been known to debate for hours such subjects as whether nectarines are peaches or plums, and whether the vegetables that Michael Field, Julia Child, and James Beard had one night at La Caravelle and said were canned were in fact canned. He roundly condemns anyone who writes more than one cookbook a year. He squarely condemns anyone who writes a cookbook containing untested recipes. Colleagues who break the rules and succeed are hailed almost as if they had happened on a new galaxy. "Paula Peck," he will say, in hushed tones of awe, "broke the rules in puff paste." If the Food Establishmentarian makes a breakthrough in cooking methods--no matter how minor and superfluous it may seem--he will celebrate. "I have just made a completely and utterly revolutionary discovery," said Poppy Cannon triumphantly one day. "I have just developed a new way of cooking asparagus."

There are two wings to the Food Establishment, each in mortal combat with the other. On the one side are the revolutionaries--as they like to think of themselves--the home economists and writers and magazine editors who are industry-minded and primarily concerned with the needs of the average housewife. Their virtues are performance, availability of product, and less work for mother; their concern is with improving American food. "There is an awe about Frenchiness in food which is terribly precious and has kept American food from being as good as it could be," says Poppy Cannon, the leader of the revolutionaries. "People think French cooking is gooking it up. All this kowtowing to so-called French food has really been a hindrance rather than a help." The revolutionaries pride themselves on discovering short cuts and developing convenience foods; they justify the compromises they make and the loss of taste that results by insisting that their recipes, while unquestionably not as good as the originals, are probably a good deal better than what the American housewife would prepare if left to her own devices. When revolutionaries get together, they talk about the technical aspects of food: how to ripen a tomato, for example; and whether the extra volume provided by beating eggs with a wire whisk justifies not using the more convenient electric beater.