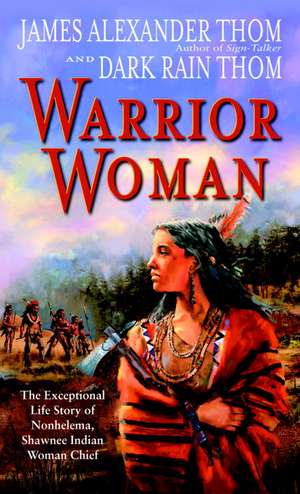

Warrior Woman: The Exceptional Life Story of Nonhelema, Shawnee Indian Woman Chief

Autor Dark Rain Thom, James Alexander Thomen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2004

Her name was Nonhelema. Literate, lovely, imposing at over six feet tall, she was the Women’s Peace Chief of the Shawnee Nation–and already a legend when the most decisive decade of her life began in 1774. That fall, with more than three thousand Virginians poised to march into the Shawnees’ home, Nonhelema’s plea for peace was denied. So she loyally became a fighter, riding into battle covered in war paint. When the Indians ran low on ammunition, Nonhelema’s role changed back to peacemaker, this time tragically.

Negotiating an armistice with military leaders of the American Revolution like Daniel Boone and George Rogers Clark, she found herself estranged from her own people–and betrayed by her white adversaries, who would murder her loved ones and eventually maim Nonhelema herself.

Throughout her inspiring life, she had many deep and complex relationships, including with her daughter, Fani, who was an adopted white captive . . . a pious and judgmental missionary, Zeisberger . . . a series of passionate lovers . . . and, in a stunning creation of the Thoms, Justin Case–a cowardly soldier transformed by the courage he saw in the female Indian leader.

Filled with the uncanny period detail and richly rendered drama that are Thom trademarks, Warrior Woman is a memorable novel of a remarkable person–one willing to fight to avoid war, by turns tough and tender, whose heart was too big for the world she wished to tame.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 54.19 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 81

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.37€ • 10.79$ • 8.56£

10.37€ • 10.79$ • 8.56£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345445551

ISBN-10: 0345445554

Pagini: 512

Dimensiuni: 106 x 174 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Mass Market.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345445554

Pagini: 512

Dimensiuni: 106 x 174 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Mass Market.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Notă biografică

James Alexander Thom was formerly a U.S. Marine, a newspaper and magazine editor, and a member of the faculty at the Indiana University Journalism School. He is the acclaimed author of Follow the River; Long Knife; From Sea to Shining Sea; Panther in the Sky, for which he won the prestigious Western Writers of America Spur Award for best historical novel; The Children of First Man; The Red Heart; and Sign-Talker. He lives in the Indiana hill country near Bloomington with his wife, Dark Rain, of the Shawnee Nation, United Remnant Band. Dark Rain is a member of the National Council, which is planning the Lewis and Clark bicentennial celebration.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Nonhelema’s Town, Scioto Valley Hunter’s Moon 1774

At this time of year, the first sunlight to come over the horizon shone through the one little window in the eastern wall of her house and illuminated the mirror on the western wall. Its reflection went back to the eastern wall, where it lit up two crosses that were her most cherished gifts.

One cross was a carved wooden crucifix hung on the log wall, with the suffering bleeding Jesus carved from cherry wood, Jesus with the long-muscled physique of a warrior, a body just like that of her first husband, who had died in one of the smallpox plagues brought by the whitemen. The crucifix had been a gift to her from Brother Schmick, a Moravian missionary whose family had been adopted by Chief Cornstalk, her brother.

The other gift glowing in the reflected sunlight, under the crucifix, was the pair of silver-trimmed pistols that the trader George Morgan had given to her when she was his guide and interpreter among the Shawnees, all along the Spaylaywesipe, or Ohio River, from Fort Pitt to as far as the Mississippi. In those years, she had lived with him and borne him a son whom she had named after him. The pistols were propped inside the open lid of their felt-lined case with their barrels crossed, and the sunlight on the red felt gave off a bloodred glow in that part of the dim room.

Another light, at the end of the room, was the cooking fire on the hearth, where her daughter, Fani, was boiling tea water and cooking griddle cakes. Fani was slender, pretty, and reticent; a widow already at less than twenty years of age. Fani had been born white. Nonhelema had adopted her when she was an orphaned child, carried in by a war party during the war between the English and French. She had no memory of being anything but Shawnee. She looked and thought Shawnee and was devoted to the people but especially so to her mother.

Many women were here from the other Shawnee towns to attend the Women’s Council and vote on the war, and they had to be fed. Fani was dutifully preparing to feed many of them. The morning air outside Nonhelema’s house was full of voices. In the sleeping loft upstairs, waking women were talking low. All night, the men’s war drum had been like a heartbeat outside her town, in the camp of Pucsinwah, the principal war chief.

This morning before sunrise, Nonhelema had washed herself in the creek and had smoked a prayer pipe at the water’s edge, blowing toward heaven the smoke carrying her prayer that she could persuade the women to vote for peace. Then she had come back to her house and made the same prayer to the God who was the father of Jesus.

The missionary Zeisberger had often scolded her that she should pray only to his God and quit praying to her people’s Great Good Spirit Weshemonetoo, but this was too important to her people for her not to pray to their own god. Two Virginian armies were coming to attack this place where most of the Shawnee main towns lay within a day’s walk of each other. The armies were coming by two routes, and when they joined together they would make one army of three or four thousand men. All the Shawnees and their allies together had been able to gather only about a thousand warriors.

Nonhelema and her brother Cornstalk believed it would be useless to fight such an army, and had been arguing so. They wanted to meet with the army leader, the governor of Virginia Colony, to plead for peace, to define boundaries. More than any of their people, Nonhelema and Cornstalk had traveled in the whiteman’s cities in the East, and knew that whitemen were too numerous to count, and had horses and wagons and cannon and muskets without limit, and would always be able to send five or more armies if they lost one battle.

That was her argument, and it had been Cornstalk’s argument also in the war council.

But Pucsinwah of the Kispoko warrior sept believed that if either half of the Virginia army could be ambushed and defeated before the halves could join together, the Virginians would flee with their tails between their legs and never dare come into the Kentucke or Ohio country again. Pucsinwah was a fiery talker and a greathearted chief who had never lost a battle, a man said to be impossible to kill, and he had convinced the Tribal Council that if the Shawnees begged for peace now, the Virginians would lose the respect and fear they had of the Shawnee nation, and then would never stop coming. Nonhelema remembered what he had said in council: “Their fear of us is a part of our strength. The other part of our strength is that the Master-of-Life knows we are right. Weshe catweloo k’weshe lawehpah! The Creator put us here, not the Long Knives! He knows we are right and will not let us be defeated in our own country!”

Upon those words the warriors had all howled, and when the hands were counted, those wanting to go and attack the Virginians had prevailed.

But now the war chief had to persuade the Women’s Council to support the war. If the Women’s Council said no, it would be useless to try to make a tribal war. The women had concerns that were beyond the understanding of the men, and the men had to heed the decision of Women’s Council.

Nonhelema moved the mirror and set it up on the table in the middle of the room. She sat down, the sunlight on her face, and looked at herself in the mirror.

Nonhelema’s name meant “not a man.” She was taller and stronger than most men. British officers called her the Grenadier Squaw because her stature and bearing were like those of their giant grenadier soldiers, who marched at the right of the ranks.

The face in the mirror had always been one of her advantages. She knew that, of course, but she was not vain of it. Men had made fools of themselves upon being struck by the sight of her. But no man had been more foolish, or more often foolish, than she had been in response to their foolishness. They had given her as much as men, with their understanding, could give, and she had given back more. It had gained her and cost her equally.

George Morgan used to tell her that she was as handsome as beautiful, and as beautiful as handsome, and both within. That was a man who could make love with words.

Brother David Zeisberger had never said a word about her appearance, but she knew that, as a missionary, he saw trouble in it.

Old Colonel Croghan, at Fort Pitt, for all his power, doted and drooled and leered.

Women, even beautiful women, envied and resented her, unless they knew her well. Her daughter, who knew her best, was devoted to her, even though their beliefs were different on most important matters.

Nonhelema’s face was built of strong planes, not coy curves, and her eyes were full of level, direct power. Her brother Cornstalk could humble men with a straight gaze, and she was almost his twin, though years older.

She herself had lived nearly fifty years, but no frailty showed in her face or body. One had to be this close to a mirror to see the white hairs in her black mane, or the tiny wrinkles around her mouth and the corners of her eyes. She had lived large, and that had sustained her. She had known as much joy as tribulation.

And in her spirit she saw two gods—her own and the Jesus God. And though they sometimes vied within her, and perhaps were just two names for the same one, together they gave her a greater soul than most people, who had only one god or another.

She folded back the flaps of a deerskin bag, took out a silver jar the size of a walnut, and pried off its lid. Inside was caked vermillion. She licked and dabbed the tip of her little finger and made a dot on her left cheekbone, then another on her right, and with another touch laid a line of red in the part of her hair. The red was the heart of Creator, Weshemonetoo, who had instructed Shawnee women to wear this heart-color so that he would recognize them as his People when the time came to die and there would be all that rush and confusion.

Now Nonhelema was ready, and it was time to call the women together for the council that would decide for war or peace.

Like her sisters the Shawnee women, who were strong and smart, she would listen to Pucsinwah’s arguments for going to fight.

Unlike her Shawnee sisters, she knew in her heart, as Brother David Zeisberger had told her, that “The peacemakers are blessed, for the peacemakers will be called the children of God, Matthew five three eleven.”

Now she was ready to persuade those people, whom she loved more than she loved her own life, to do what was for their own good: to make peace.

It was midday when the war chief came up the hill and made his formal request to speak to the great circle of women who sat on logs and blankets in the shade of the towering trees. The leaves were yellow and red, and some were already dropping off and tumbling through the air. The ground in the council circle was carpeted with their colors. This Council Hill and Burning Ground of Nonhelema’s Town was the grandest place in the valley of the Scioto-sipe, a lookout from which the whole Pickaway Plains could be seen in every direction, flanked by wooded ridges so distant that they looked blue in the autumn haze. Any army that marched toward this place could be seen from here half a day before it arrived.

Nonhelema brought Pucsinwah into the center of the circle, where a fragrant fire of red cedar burned within a ring of stones. This chief of the Kispoko warrior sept was a tall man, and of a stature that made him seem still taller, but the crown of his head was level with her jaw. There was no man of greater courage and honor in the Shawnee nation and she admired him, even though he was here to speak as her adversary. Pucsinwah’s wife, Methotase, A-Turtle-Laying-Her-Eggs-in-the-Sand, was already seated here in the circle. She was a beautiful Shawnee woman from their Creek community in the south. She was famous in her own right as a giver of extraordinary births. Six years before, a great, green shooting star had crossed the sky at the moment she gave birth to a son, who had been named Tecumseh, Panther-Crossing-the-Sky. Three years later, she had been the first woman ever known to have borne three boys at once, all three alive and healthy. Methotase was a wise and strong woman, and likely Pucksinwah himself did not know whether she would vote with her husband for war, or against him for peace. Her oldest son, Chiksika, was of warrior age and would be in battle beside his father if the women approved of the war plan.

Nonhelema knelt at the fire and with a burning stick she lit the ceremonial pipe, turned to the Four Winds, and exhaled the aromatic kinnikinnick smoke toward the earth and heaven. Then she passed the pipe to Pucsinwah, who repeated the process. Then the pipe was given to Methotase, who drew on it and handed it to the woman on her left, starting it on its way around the circle.

Nonhelema began her prayer: “Kijilamuhka-ong, He-Who-Creates-by-Thinking, Master-of-Life: This smoke comes to you bearing our prayers. We promise to speak true in this council. We ask you to see us doing right by your intentions, as we deliberate on the blood and the honor of your People of the Southwind. Have pity on us. Help us use all the wisdom that you gave us, for we know there is no matter more important than this one now before us. It will fall upon our children, and their children. As we begin, open our ears to the words of our esteemed wapacoli oukimeh, the war chief Pucsinwah who stands among us. When he has spoken out, he will retire away and wait for us to council. Each woman here who wishes will speak to all of us, for war or for peace. Listen to us, Kijilamuhka-ong, and give your blessing to the answer we will collect from our wise women.”

And God of Jesus, likewise, she thought, remembering the missionary. “All my sisters,” she said, “listen well now to the wapicoli oukimeh.”

As much of Pucsinwah’s greatness as a war chief lay in his good judgment as in his skill and courage. He was not reckless, and all his strategies minimized the risks to his warriors’ lives. Nonhelema admired him as a man who defended his people but held their lives precious. Now Pucksinwah stood in the center of the circle of women and turned all the way around, with one hand outstretched as if to include all of them in a salute. Hundreds of women were gathered on this hill, and he had to speak in full voice to be heard by them all.

“Ketawpi, women of the council. Listen:

“You, the mothers and wives and sisters and daughters, it is you who carry the Southwind People from generation to generation. It is you who give birth to the people, and feed and heal them, and who bury them. You have put more into the lives of the warriors than the warriors themselves have done, and you dread most and suffer most the loss of their lives in battle. Knowing that, I come to you with grave respect and ask for your ears and your hearts. Ketawpi:

“War is the last thing to do, when there is nothing else that can be done. The Southwind People, and this land where Creator put us to live, are being attacked by an army of the Long Knives from Virginia. Their headman, called Governor Dunmore, leads them. He declares that he is coming to punish the Shawnee people. But the Shawnee people have done nothing to his people. In truth, he wants to put us out of our hunting grounds. He pretends!”

From the Hardcover edition.

Nonhelema’s Town, Scioto Valley Hunter’s Moon 1774

At this time of year, the first sunlight to come over the horizon shone through the one little window in the eastern wall of her house and illuminated the mirror on the western wall. Its reflection went back to the eastern wall, where it lit up two crosses that were her most cherished gifts.

One cross was a carved wooden crucifix hung on the log wall, with the suffering bleeding Jesus carved from cherry wood, Jesus with the long-muscled physique of a warrior, a body just like that of her first husband, who had died in one of the smallpox plagues brought by the whitemen. The crucifix had been a gift to her from Brother Schmick, a Moravian missionary whose family had been adopted by Chief Cornstalk, her brother.

The other gift glowing in the reflected sunlight, under the crucifix, was the pair of silver-trimmed pistols that the trader George Morgan had given to her when she was his guide and interpreter among the Shawnees, all along the Spaylaywesipe, or Ohio River, from Fort Pitt to as far as the Mississippi. In those years, she had lived with him and borne him a son whom she had named after him. The pistols were propped inside the open lid of their felt-lined case with their barrels crossed, and the sunlight on the red felt gave off a bloodred glow in that part of the dim room.

Another light, at the end of the room, was the cooking fire on the hearth, where her daughter, Fani, was boiling tea water and cooking griddle cakes. Fani was slender, pretty, and reticent; a widow already at less than twenty years of age. Fani had been born white. Nonhelema had adopted her when she was an orphaned child, carried in by a war party during the war between the English and French. She had no memory of being anything but Shawnee. She looked and thought Shawnee and was devoted to the people but especially so to her mother.

Many women were here from the other Shawnee towns to attend the Women’s Council and vote on the war, and they had to be fed. Fani was dutifully preparing to feed many of them. The morning air outside Nonhelema’s house was full of voices. In the sleeping loft upstairs, waking women were talking low. All night, the men’s war drum had been like a heartbeat outside her town, in the camp of Pucsinwah, the principal war chief.

This morning before sunrise, Nonhelema had washed herself in the creek and had smoked a prayer pipe at the water’s edge, blowing toward heaven the smoke carrying her prayer that she could persuade the women to vote for peace. Then she had come back to her house and made the same prayer to the God who was the father of Jesus.

The missionary Zeisberger had often scolded her that she should pray only to his God and quit praying to her people’s Great Good Spirit Weshemonetoo, but this was too important to her people for her not to pray to their own god. Two Virginian armies were coming to attack this place where most of the Shawnee main towns lay within a day’s walk of each other. The armies were coming by two routes, and when they joined together they would make one army of three or four thousand men. All the Shawnees and their allies together had been able to gather only about a thousand warriors.

Nonhelema and her brother Cornstalk believed it would be useless to fight such an army, and had been arguing so. They wanted to meet with the army leader, the governor of Virginia Colony, to plead for peace, to define boundaries. More than any of their people, Nonhelema and Cornstalk had traveled in the whiteman’s cities in the East, and knew that whitemen were too numerous to count, and had horses and wagons and cannon and muskets without limit, and would always be able to send five or more armies if they lost one battle.

That was her argument, and it had been Cornstalk’s argument also in the war council.

But Pucsinwah of the Kispoko warrior sept believed that if either half of the Virginia army could be ambushed and defeated before the halves could join together, the Virginians would flee with their tails between their legs and never dare come into the Kentucke or Ohio country again. Pucsinwah was a fiery talker and a greathearted chief who had never lost a battle, a man said to be impossible to kill, and he had convinced the Tribal Council that if the Shawnees begged for peace now, the Virginians would lose the respect and fear they had of the Shawnee nation, and then would never stop coming. Nonhelema remembered what he had said in council: “Their fear of us is a part of our strength. The other part of our strength is that the Master-of-Life knows we are right. Weshe catweloo k’weshe lawehpah! The Creator put us here, not the Long Knives! He knows we are right and will not let us be defeated in our own country!”

Upon those words the warriors had all howled, and when the hands were counted, those wanting to go and attack the Virginians had prevailed.

But now the war chief had to persuade the Women’s Council to support the war. If the Women’s Council said no, it would be useless to try to make a tribal war. The women had concerns that were beyond the understanding of the men, and the men had to heed the decision of Women’s Council.

Nonhelema moved the mirror and set it up on the table in the middle of the room. She sat down, the sunlight on her face, and looked at herself in the mirror.

Nonhelema’s name meant “not a man.” She was taller and stronger than most men. British officers called her the Grenadier Squaw because her stature and bearing were like those of their giant grenadier soldiers, who marched at the right of the ranks.

The face in the mirror had always been one of her advantages. She knew that, of course, but she was not vain of it. Men had made fools of themselves upon being struck by the sight of her. But no man had been more foolish, or more often foolish, than she had been in response to their foolishness. They had given her as much as men, with their understanding, could give, and she had given back more. It had gained her and cost her equally.

George Morgan used to tell her that she was as handsome as beautiful, and as beautiful as handsome, and both within. That was a man who could make love with words.

Brother David Zeisberger had never said a word about her appearance, but she knew that, as a missionary, he saw trouble in it.

Old Colonel Croghan, at Fort Pitt, for all his power, doted and drooled and leered.

Women, even beautiful women, envied and resented her, unless they knew her well. Her daughter, who knew her best, was devoted to her, even though their beliefs were different on most important matters.

Nonhelema’s face was built of strong planes, not coy curves, and her eyes were full of level, direct power. Her brother Cornstalk could humble men with a straight gaze, and she was almost his twin, though years older.

She herself had lived nearly fifty years, but no frailty showed in her face or body. One had to be this close to a mirror to see the white hairs in her black mane, or the tiny wrinkles around her mouth and the corners of her eyes. She had lived large, and that had sustained her. She had known as much joy as tribulation.

And in her spirit she saw two gods—her own and the Jesus God. And though they sometimes vied within her, and perhaps were just two names for the same one, together they gave her a greater soul than most people, who had only one god or another.

She folded back the flaps of a deerskin bag, took out a silver jar the size of a walnut, and pried off its lid. Inside was caked vermillion. She licked and dabbed the tip of her little finger and made a dot on her left cheekbone, then another on her right, and with another touch laid a line of red in the part of her hair. The red was the heart of Creator, Weshemonetoo, who had instructed Shawnee women to wear this heart-color so that he would recognize them as his People when the time came to die and there would be all that rush and confusion.

Now Nonhelema was ready, and it was time to call the women together for the council that would decide for war or peace.

Like her sisters the Shawnee women, who were strong and smart, she would listen to Pucsinwah’s arguments for going to fight.

Unlike her Shawnee sisters, she knew in her heart, as Brother David Zeisberger had told her, that “The peacemakers are blessed, for the peacemakers will be called the children of God, Matthew five three eleven.”

Now she was ready to persuade those people, whom she loved more than she loved her own life, to do what was for their own good: to make peace.

It was midday when the war chief came up the hill and made his formal request to speak to the great circle of women who sat on logs and blankets in the shade of the towering trees. The leaves were yellow and red, and some were already dropping off and tumbling through the air. The ground in the council circle was carpeted with their colors. This Council Hill and Burning Ground of Nonhelema’s Town was the grandest place in the valley of the Scioto-sipe, a lookout from which the whole Pickaway Plains could be seen in every direction, flanked by wooded ridges so distant that they looked blue in the autumn haze. Any army that marched toward this place could be seen from here half a day before it arrived.

Nonhelema brought Pucsinwah into the center of the circle, where a fragrant fire of red cedar burned within a ring of stones. This chief of the Kispoko warrior sept was a tall man, and of a stature that made him seem still taller, but the crown of his head was level with her jaw. There was no man of greater courage and honor in the Shawnee nation and she admired him, even though he was here to speak as her adversary. Pucsinwah’s wife, Methotase, A-Turtle-Laying-Her-Eggs-in-the-Sand, was already seated here in the circle. She was a beautiful Shawnee woman from their Creek community in the south. She was famous in her own right as a giver of extraordinary births. Six years before, a great, green shooting star had crossed the sky at the moment she gave birth to a son, who had been named Tecumseh, Panther-Crossing-the-Sky. Three years later, she had been the first woman ever known to have borne three boys at once, all three alive and healthy. Methotase was a wise and strong woman, and likely Pucksinwah himself did not know whether she would vote with her husband for war, or against him for peace. Her oldest son, Chiksika, was of warrior age and would be in battle beside his father if the women approved of the war plan.

Nonhelema knelt at the fire and with a burning stick she lit the ceremonial pipe, turned to the Four Winds, and exhaled the aromatic kinnikinnick smoke toward the earth and heaven. Then she passed the pipe to Pucsinwah, who repeated the process. Then the pipe was given to Methotase, who drew on it and handed it to the woman on her left, starting it on its way around the circle.

Nonhelema began her prayer: “Kijilamuhka-ong, He-Who-Creates-by-Thinking, Master-of-Life: This smoke comes to you bearing our prayers. We promise to speak true in this council. We ask you to see us doing right by your intentions, as we deliberate on the blood and the honor of your People of the Southwind. Have pity on us. Help us use all the wisdom that you gave us, for we know there is no matter more important than this one now before us. It will fall upon our children, and their children. As we begin, open our ears to the words of our esteemed wapacoli oukimeh, the war chief Pucsinwah who stands among us. When he has spoken out, he will retire away and wait for us to council. Each woman here who wishes will speak to all of us, for war or for peace. Listen to us, Kijilamuhka-ong, and give your blessing to the answer we will collect from our wise women.”

And God of Jesus, likewise, she thought, remembering the missionary. “All my sisters,” she said, “listen well now to the wapicoli oukimeh.”

As much of Pucsinwah’s greatness as a war chief lay in his good judgment as in his skill and courage. He was not reckless, and all his strategies minimized the risks to his warriors’ lives. Nonhelema admired him as a man who defended his people but held their lives precious. Now Pucksinwah stood in the center of the circle of women and turned all the way around, with one hand outstretched as if to include all of them in a salute. Hundreds of women were gathered on this hill, and he had to speak in full voice to be heard by them all.

“Ketawpi, women of the council. Listen:

“You, the mothers and wives and sisters and daughters, it is you who carry the Southwind People from generation to generation. It is you who give birth to the people, and feed and heal them, and who bury them. You have put more into the lives of the warriors than the warriors themselves have done, and you dread most and suffer most the loss of their lives in battle. Knowing that, I come to you with grave respect and ask for your ears and your hearts. Ketawpi:

“War is the last thing to do, when there is nothing else that can be done. The Southwind People, and this land where Creator put us to live, are being attacked by an army of the Long Knives from Virginia. Their headman, called Governor Dunmore, leads them. He declares that he is coming to punish the Shawnee people. But the Shawnee people have done nothing to his people. In truth, he wants to put us out of our hunting grounds. He pretends!”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Praise for James Alexander Thom

and Sign-Talker

“Very readable, fresh, original, and vivid.”

–LARRY MCMURTRY

“James Alexander Thom is one of the finest historical novelists writing today. He knows how to tell a cracking good yearn, cares passionately about getting his history right, and has a gift for illuminating those forgotten but fascinating corners of the American past with sheer storytelling power.”

–JOHN SUGDEN

Author of Tecumseh: A Life

“Excellent . . . It is at once an adventure story [and] a historical document . . . Even though many readers know the story of Lewis and Clark, Thom’s novel will give them new insight.”

–The Indianapolis Star (4-star review)

“The majesty of the scenery, the wonder of the stately tribes who greet, and menace, the expedition and the expedition’s mix of soldiers, ne’er-do-wells, and French traders all combine to produce a strong novel about the days when Missouri was at the edge of the map.”

–The Kansas City Star

“This great journey halfway across a wilderness continent and back has never been told so compellingly, with so much dignity and wisdom, as in Sign-Talker.”

–SCOTT RUSSELL SANDERS

Author of Hunting for Hope

From the Hardcover edition.

and Sign-Talker

“Very readable, fresh, original, and vivid.”

–LARRY MCMURTRY

“James Alexander Thom is one of the finest historical novelists writing today. He knows how to tell a cracking good yearn, cares passionately about getting his history right, and has a gift for illuminating those forgotten but fascinating corners of the American past with sheer storytelling power.”

–JOHN SUGDEN

Author of Tecumseh: A Life

“Excellent . . . It is at once an adventure story [and] a historical document . . . Even though many readers know the story of Lewis and Clark, Thom’s novel will give them new insight.”

–The Indianapolis Star (4-star review)

“The majesty of the scenery, the wonder of the stately tribes who greet, and menace, the expedition and the expedition’s mix of soldiers, ne’er-do-wells, and French traders all combine to produce a strong novel about the days when Missouri was at the edge of the map.”

–The Kansas City Star

“This great journey halfway across a wilderness continent and back has never been told so compellingly, with so much dignity and wisdom, as in Sign-Talker.”

–SCOTT RUSSELL SANDERS

Author of Hunting for Hope

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The award-winning author of "Sign Talker" and his wife, who is a member of the United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation, pen this historical novel of Nonhelema, a woman chief of the Shawnee during the 18th century.