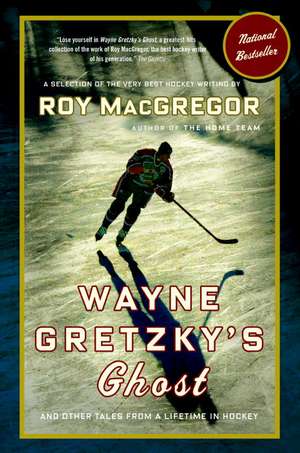

Wayne Gretzky's Ghost: And Other Tales from a Lifetime in Hockey

Autor Roy MacGregoren Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 noi 2012

Preț: 111.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.38€ • 22.24$ • 17.65£

21.38€ • 22.24$ • 17.65£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307357427

ISBN-10: 0307357422

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8 PG INSERT, COLOUR IMAGES

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

ISBN-10: 0307357422

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8 PG INSERT, COLOUR IMAGES

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

Notă biografică

ROY MacGREGOR is the acclaimed and bestselling author of Home Team: Fathers, Sons & Hockey (shortlisted for the Governor General's Literary Award); A Life in the Bush (winner of the US Rutstrum Award for Best Wilderness Book and the CAA Award for Biography); and Canadians: A Portrait of a Country and Its People, as well as two novels, Canoe Lake and The Last Season, and the popular Screech Owls mystery series for young readers. A regular columnist at the Globe and Mail, MacGregor's journalism has garnered four National Magazine Awards and eight National Newspaper Award nominations. He is an Officer of the Order of Canada, and was described in the citation as one of Canada's "most gifted storytellers." His most recent book is Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him. He lives in Kanata. The author lives in Kanata, ON.

Extras

“One more year!” the 18,500 gathered at Ottawa’s Corel Centre began to chant with 4:43 left in regulation time. “One more year! One more year! One more year!”

He heard them—he even raised his stick in salute—but he wasn’t listening. Wayne Gretzky was finished. This would be his final National Hockey League game ever played in Canada, his home country, a 2ߝ2 tie on April 15, 1999, back when the NHL still had ties, between the Ottawa Senators and his New York Rangers. It seems a silly thing to say so many years on—“his New York Rangers”—as in Canadian eyes and hearts, and even imaginations, he is an Edmonton Oiler forever.

Wayne Gretzky was thirty-eight years old that early spring day in Ottawa. He was, by his own measure, merely a shadow of what he had once been as a player. He had 61 points for his final season— “99” retiring in 1999—whereas he had once scored 215. He was, however, still the Rangers’ leading scorer, and had several of his lesser teammates only been able to finish on the perfect tape-to-tape passes from the corners, from the back of the net, that he had delivered all this game, not only would the Rangers have easily won but his point total would have been in familiar Gretzky territory.

Still, he had missed a dozen games due to a sore disc in his back. He knew it was time. He had once said he would be gone by thirty, but his great hero, Gordie Howe, who had retired early and then returned to play till age fifty-two, had warned him to “be careful not to leave the thing you love too soon.” He had continued on past thirty but would not, he swore, be hanging on at forty.

It had been a magnificent lifetime of hockey. Six teams— Indianapolis Racers and Edmonton Oilers of the World Hockey Association, the Oilers, Los Angeles Kings, St. Louis Blues and Rangers of the NHL—and he had won four Stanley Cups, all with the Oilers, while establishing a stunning sixty-one scoring records, many of which will never be broken. He had scored more goals than anyone who had ever played the game, and just to put that into context, he was never even really considered a goal scorer but a playmaker.

He had been hearing the accolades since he was ten years of age and scored 378 goals for the Nadrofsky Steelers in his hometown of Brantford. “You are a very special person,” his father, Walter, had told him around that time. “Wherever you go, probably all your life, people are going to make a fuss over you. You’ve got to remember that, and you’ve got to behave right. They’re going to be watching for every mistake. Remember that. You’re very special and you’re on display.”

On display constantly—whether scoring 92 goals one season for Edmonton, getting married to Janet Jones in Canada’s “Wedding of the Century,” getting traded to the Kings in a deal that will be debated as long as Confederation, becoming the country’s most recognizable pitchman for corporate sponsors—and measured endlessly. They called him “Whiner” Gretzky for a while. They once said he skated like a man carrying a piano on his back when he went through his first back troubles. They blamed his wife for the trade to Hollywood, where she was an actress. Yet if there were minor stumbles there was never a fall, almost impossible to imagine in this era of over-the-top sports celebrity, temptation and gotcha journalism. He never forgot Walter Gretzky’s good advice.

They tried, but could never quite describe the magic he brought to the ice. Gordie Howe jokingly suggested that if they parted the hair at the back of his head, they would find another eye. Broadcaster Peter Gzowski said he had the ability to move about the ice like a whisper. It was said he could pass through opponents like an X-ray. He himself liked to say he didn’t skate to where the puck was, but to where it was going to be. During the 1987 Canada Cup—when he so brilliantly set up the Mario Lemieux goal that won the tournament— Igor Dmitriev, a coach with the Soviet team, said: “Gretzky is like an invisible man. He appears out of nowhere, passes to nowhere, and a goal is scored.” No one has ever said it better.

But here in Ottawa on April 15, 1999, the invisible man seemed like the only man on the ice by the end. Walter Gretzky and his buddies from Brantford were on their feet, Janet and their three children, Paulina, Trevor and Ty, were on their feet. The NHL commissioner was on his feet. There is no possible count of the millions watching on television who were on their feet, but it is a fair bet that a great many were.

“Gret-zky!” the crowd chanted as the final minute came around.

“Gret-zky!”

“Gret-zky!”

“Gret-zky! Gret-zky! Gret-zky!”

The horn blew to signal the end of overtime, still a tie, and both teams remained on the ice while the cheers poured down. Then, with a gentle shrug of his shoulders, Ottawa defenceman Igor Kravchuk broke with the usual protocol and led his teammates over to shake Gretzky’s hand and thank him.

It was over.

Months passed between Wayne Gretzky’s retirement from hockey and a meeting that took place later that summer at the National Post’s main offices on Don Mills Road in Toronto. The newspaper’s publisher, Gordon Fisher, said he had something important to discuss with me. I was invited to a meeting with him, editor Ken Whyte and sports editor Graham Parley. It was all to be kept top secret. I had no idea when I entered the room what was up.

“We’re bringing on a new sports columnist,” Ken said with his enigmatic smile. A new sports columnist? I wondered. They already had Cam Cole, the best in the business—snatched from the Edmonton Journal—and I was pitching in regularly as well as doing some political work. What did we need with another sports columnist?

“He’ll be writing hockey,” Ken said. I blanched. But . . . but . . . but I write hockey. And Cam writes hockey.

“It’s Wayne Gretzky,” Gordon finally said.

I remember giving my head a shake. Wayne Gretzky? As a hockey columnist? How did they even know he could type, let alone write?

“It’s a huge coup for us,” said Gordon. “This will get us a lot of publicity and bring in a lot of readers. He has one condition, though.”

“What’s that?” I asked, half expecting to be told to back off and stay out of the rinks.

Gordon smiled. “He wants to work with you.”

“We want you to be his ghostwriter,” added Ken.

Gretzky’s agent, Mike Barnett, had done the negotiations for the column and this request had been part of the deal. No one but the senior executives knew what the financial part of the deal was to be—rumours went as high as $200,000, as low as for free in order to keep the recently retired player in the public eye—but soon everyone at the paper, and many beyond, would know that I was also part of the agreement.

This quite surprised me. We hardly knew each other. Unlike Cam, I had never covered the Oilers in their glory years. I had even, long, long ago, written one column, tongue rather in check, suggesting Wayne Gretzky was the worst thing that ever happened to hockey— his brilliance and popularity causing NHL expansion to places that made no sense, his high ability raising fans’ expectations for skill level that would sag once he retired—and I had even gone on the CBC’s As It Happens back in the summer of 1988 to predict, with uncanny foresight, that Gretzky would be swallowed up in Hollywood and never heard of again. Instead, of course, he became even more famous in the years that followed.

In the late fall of 1994, however, I joined a handful of other journalists to accompany the “99 All-Stars” on a barnstorming trip to Europe during the NHL’s first owners’ lockout. It was mostly a lark: Gretzky and pals like Brett Hull, Paul Coffey, Marty McSorley and Mark Messier heading off on a tour of Europe with their hockey bags, wives and girlfriends and even, in the case of Gretzky, McSorley, Messier and Coffey, their dads. They played in Finland, including one game in Helsinki where Jari Kurri joined the fun, Sweden, including matches against teams featuring the likes of Kent (Magic) Nilsson and Mats Naslund, Norway and Germany. It was a wonderful experience, the stories filed back to Canada given wonderful play by newspapers starving for hockey and the stories, many untold, of the trip itself something to be treasured forever.

In the intervening years, we’d become casually friendly as Gretzky moved to St. Louis and then on to New York to round out his career. His kids, along with the children of Mike Barnett, were even reading the Screech Owls hockey mystery series. Gordon Fisher asked if I would agree to help out the paper by dropping one of my four weekly columns and using that time to help out. Of course, I agreed. He was, after all, the publisher. And besides, it sounded like fun.

From the Hardcover edition.

He heard them—he even raised his stick in salute—but he wasn’t listening. Wayne Gretzky was finished. This would be his final National Hockey League game ever played in Canada, his home country, a 2ߝ2 tie on April 15, 1999, back when the NHL still had ties, between the Ottawa Senators and his New York Rangers. It seems a silly thing to say so many years on—“his New York Rangers”—as in Canadian eyes and hearts, and even imaginations, he is an Edmonton Oiler forever.

Wayne Gretzky was thirty-eight years old that early spring day in Ottawa. He was, by his own measure, merely a shadow of what he had once been as a player. He had 61 points for his final season— “99” retiring in 1999—whereas he had once scored 215. He was, however, still the Rangers’ leading scorer, and had several of his lesser teammates only been able to finish on the perfect tape-to-tape passes from the corners, from the back of the net, that he had delivered all this game, not only would the Rangers have easily won but his point total would have been in familiar Gretzky territory.

Still, he had missed a dozen games due to a sore disc in his back. He knew it was time. He had once said he would be gone by thirty, but his great hero, Gordie Howe, who had retired early and then returned to play till age fifty-two, had warned him to “be careful not to leave the thing you love too soon.” He had continued on past thirty but would not, he swore, be hanging on at forty.

It had been a magnificent lifetime of hockey. Six teams— Indianapolis Racers and Edmonton Oilers of the World Hockey Association, the Oilers, Los Angeles Kings, St. Louis Blues and Rangers of the NHL—and he had won four Stanley Cups, all with the Oilers, while establishing a stunning sixty-one scoring records, many of which will never be broken. He had scored more goals than anyone who had ever played the game, and just to put that into context, he was never even really considered a goal scorer but a playmaker.

He had been hearing the accolades since he was ten years of age and scored 378 goals for the Nadrofsky Steelers in his hometown of Brantford. “You are a very special person,” his father, Walter, had told him around that time. “Wherever you go, probably all your life, people are going to make a fuss over you. You’ve got to remember that, and you’ve got to behave right. They’re going to be watching for every mistake. Remember that. You’re very special and you’re on display.”

On display constantly—whether scoring 92 goals one season for Edmonton, getting married to Janet Jones in Canada’s “Wedding of the Century,” getting traded to the Kings in a deal that will be debated as long as Confederation, becoming the country’s most recognizable pitchman for corporate sponsors—and measured endlessly. They called him “Whiner” Gretzky for a while. They once said he skated like a man carrying a piano on his back when he went through his first back troubles. They blamed his wife for the trade to Hollywood, where she was an actress. Yet if there were minor stumbles there was never a fall, almost impossible to imagine in this era of over-the-top sports celebrity, temptation and gotcha journalism. He never forgot Walter Gretzky’s good advice.

They tried, but could never quite describe the magic he brought to the ice. Gordie Howe jokingly suggested that if they parted the hair at the back of his head, they would find another eye. Broadcaster Peter Gzowski said he had the ability to move about the ice like a whisper. It was said he could pass through opponents like an X-ray. He himself liked to say he didn’t skate to where the puck was, but to where it was going to be. During the 1987 Canada Cup—when he so brilliantly set up the Mario Lemieux goal that won the tournament— Igor Dmitriev, a coach with the Soviet team, said: “Gretzky is like an invisible man. He appears out of nowhere, passes to nowhere, and a goal is scored.” No one has ever said it better.

But here in Ottawa on April 15, 1999, the invisible man seemed like the only man on the ice by the end. Walter Gretzky and his buddies from Brantford were on their feet, Janet and their three children, Paulina, Trevor and Ty, were on their feet. The NHL commissioner was on his feet. There is no possible count of the millions watching on television who were on their feet, but it is a fair bet that a great many were.

“Gret-zky!” the crowd chanted as the final minute came around.

“Gret-zky!”

“Gret-zky!”

“Gret-zky! Gret-zky! Gret-zky!”

The horn blew to signal the end of overtime, still a tie, and both teams remained on the ice while the cheers poured down. Then, with a gentle shrug of his shoulders, Ottawa defenceman Igor Kravchuk broke with the usual protocol and led his teammates over to shake Gretzky’s hand and thank him.

It was over.

Months passed between Wayne Gretzky’s retirement from hockey and a meeting that took place later that summer at the National Post’s main offices on Don Mills Road in Toronto. The newspaper’s publisher, Gordon Fisher, said he had something important to discuss with me. I was invited to a meeting with him, editor Ken Whyte and sports editor Graham Parley. It was all to be kept top secret. I had no idea when I entered the room what was up.

“We’re bringing on a new sports columnist,” Ken said with his enigmatic smile. A new sports columnist? I wondered. They already had Cam Cole, the best in the business—snatched from the Edmonton Journal—and I was pitching in regularly as well as doing some political work. What did we need with another sports columnist?

“He’ll be writing hockey,” Ken said. I blanched. But . . . but . . . but I write hockey. And Cam writes hockey.

“It’s Wayne Gretzky,” Gordon finally said.

I remember giving my head a shake. Wayne Gretzky? As a hockey columnist? How did they even know he could type, let alone write?

“It’s a huge coup for us,” said Gordon. “This will get us a lot of publicity and bring in a lot of readers. He has one condition, though.”

“What’s that?” I asked, half expecting to be told to back off and stay out of the rinks.

Gordon smiled. “He wants to work with you.”

“We want you to be his ghostwriter,” added Ken.

Gretzky’s agent, Mike Barnett, had done the negotiations for the column and this request had been part of the deal. No one but the senior executives knew what the financial part of the deal was to be—rumours went as high as $200,000, as low as for free in order to keep the recently retired player in the public eye—but soon everyone at the paper, and many beyond, would know that I was also part of the agreement.

This quite surprised me. We hardly knew each other. Unlike Cam, I had never covered the Oilers in their glory years. I had even, long, long ago, written one column, tongue rather in check, suggesting Wayne Gretzky was the worst thing that ever happened to hockey— his brilliance and popularity causing NHL expansion to places that made no sense, his high ability raising fans’ expectations for skill level that would sag once he retired—and I had even gone on the CBC’s As It Happens back in the summer of 1988 to predict, with uncanny foresight, that Gretzky would be swallowed up in Hollywood and never heard of again. Instead, of course, he became even more famous in the years that followed.

In the late fall of 1994, however, I joined a handful of other journalists to accompany the “99 All-Stars” on a barnstorming trip to Europe during the NHL’s first owners’ lockout. It was mostly a lark: Gretzky and pals like Brett Hull, Paul Coffey, Marty McSorley and Mark Messier heading off on a tour of Europe with their hockey bags, wives and girlfriends and even, in the case of Gretzky, McSorley, Messier and Coffey, their dads. They played in Finland, including one game in Helsinki where Jari Kurri joined the fun, Sweden, including matches against teams featuring the likes of Kent (Magic) Nilsson and Mats Naslund, Norway and Germany. It was a wonderful experience, the stories filed back to Canada given wonderful play by newspapers starving for hockey and the stories, many untold, of the trip itself something to be treasured forever.

In the intervening years, we’d become casually friendly as Gretzky moved to St. Louis and then on to New York to round out his career. His kids, along with the children of Mike Barnett, were even reading the Screech Owls hockey mystery series. Gordon Fisher asked if I would agree to help out the paper by dropping one of my four weekly columns and using that time to help out. Of course, I agreed. He was, after all, the publisher. And besides, it sounded like fun.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Wayne Gretzky's Ghost will make the perfect gift.... This very personal collection offers an unique inside look from someone who has made a living--and a lifetime--out of loving Canada's game." CBC Books

"The Harper government should just go ahead and designate Roy MacGregor a national treasure and be done with it.... Next time you're watching the game and Don Cherry comes on, do yourself a favour. Hit the mute button and read a couple of MacGregor pieces instead. You'll be glad you did." Ottawa Citizen

"The best hockey writer of his generation." The Gazette

"Illuminates many corners of the game.... Brings the perspective of not only of a reporter, but of a fan, and player." Winnipeg Free Press

"The Harper government should just go ahead and designate Roy MacGregor a national treasure and be done with it.... Next time you're watching the game and Don Cherry comes on, do yourself a favour. Hit the mute button and read a couple of MacGregor pieces instead. You'll be glad you did." Ottawa Citizen

"The best hockey writer of his generation." The Gazette

"Illuminates many corners of the game.... Brings the perspective of not only of a reporter, but of a fan, and player." Winnipeg Free Press