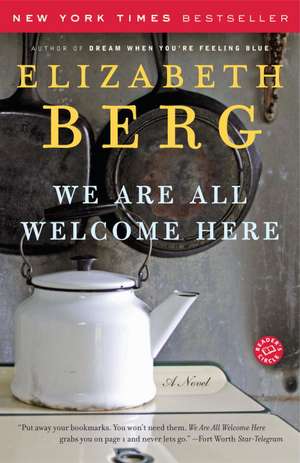

We Are All Welcome Here

Autor Elizabeth Bergen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2007

It is the summer of 1964. In Tupelo, Mississippi, the town of Elvis’s birth, tensions are mounting over civil-rights demonstrations occurring ever more frequently–and violently–across the state. But in Paige Dunn’s small, ramshackle house, there are more immediate concerns. Challenged by the effects of the polio she contracted during her last month of pregnancy, Paige is nonetheless determined to live as normal a life as possible and to raise her daughter, Diana, in the way she sees fit–with the support of her tough-talking black caregiver, Peacie.

Diana is trying in her own fashion to live a normal life. As a fourteen-year-old, she wants to make money for clothes and magazines, to slough off the authority of her mother and Peacie, to figure out the puzzle that is boys, and to escape the oppressiveness she sees everywhere in her small town. What she can never escape, however, is the way her life is markedly different from others’. Nor can she escape her ongoing responsibility to assist in caring for her mother. Paige Dunn is attractive, charming, intelligent, and lively, but her needs are great–and relentless.

As the summer unfolds, hate and adversity will visit this modest home. Despite the difficulties thrust upon them, each of the women will find her own path to independence, understanding, and peace. And Diana’s mother, so mightily compromised, will end up giving her daughter an extraordinary gift few parents could match.

Preț: 109.87 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 165

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.02€ • 22.11$ • 17.37£

21.02€ • 22.11$ • 17.37£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812971002

ISBN-10: 0812971000

Pagini: 206

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0812971000

Pagini: 206

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Extras

Chapter 1

The sun was barely up when I crept downstairs. I had awakened early again, full of a pulsating need to get out and get things done, though if the truth be told, I was not fully certain what those things were. I had recently turned thirteen and was being yanked about by hormones that had me weeping one moment and yelling the next; rapturously practice-kissing the inside of my elbow one moment, then crossing the street to avoid boys the next. I alternated between periods of extreme confidence and bouts of quivering insecurity. Life was curiously exhausting but also exhilarating.

I longed for things I’d never wanted before: clothes that conferred upon the wearer inalienable status, makeup that apparently transformed not only the face but the soul. But mostly I wanted a kind of inner strength that would offer protection against the small-town injustices I had long endured, something that would let me take pride in myself as myself. I focused on making money, because I believed that despite what people said, money could buy happiness. I knew beyond knowing that this was the summer I would get that money. All I had to figure out was how.

I crept into the dining room and made sure my mother was sleeping soundly, then slipped out onto the front porch. I wanted to be alone to unravel my restlessness, to soothe myself by making plans for the day being born before me. I stretched, then stood with my hands on my hips to survey the street on this already hot July day. It was dead as usual, no activity seen inside or out of the tiny houses with their sagging porches, their dented mailboxes, their yards mostly gone to dust. I walked down the steps and started for a patch of dandelions growing against the side of the house. I would use them to brighten my desk, where today I would be writing a letter to Sandra Dee. I wrote often to movie stars, letting them know that I, too, was an actress and also a playwright, just in case they might be looking for someone.

I did not get back inside quickly enough, for I heard a car door slam and looked over to see Peacie, her skinny self walking slowly toward our house, swinging her big black purse. She was wearing a red-and-white polka-dot housedress, the great big polka dots that looked like poker chips, and blindingly white ankle socks with her black men’s shoes, and inside her purse was the flowered apron she’d put on as soon as she stepped inside. When she left, she’d carry that apron home in a brown paper bag to wash in her own automatic washing machine—she did not like our wringer model.

I ran under the porch, praying she hadn’t seen me, wishing I’d known her boyfriend, LaRue, was going to drop her off. If I’d known that, I’d have stayed in the house so that I could have run out and visited with him. LaRue often brought me presents: Moon Pies or Goo-Goo Clusters, Popsicle sticks for the little houses I liked to build, puppets he’d made from socks, and on one memorable occasion, a silver dollar he’d won shooting craps. He could balance a goober on the end of his nose and then flip it into his mouth. He was a highly imaginative dresser; he once wore a tie made from the Sunday comics, for example. He favored electric colors and had white bucks on which he’d drawn intricate designs in black ink. He cooked bacon with brown sugar, chili powder, and pecans—praline bacon, he called it—and it was delicious. He told jokes that I could understand. He drank coffee out of a saucer and made it look elegant.

LaRue tooted his horn to Peacie and drove off. I thought quickly about what my options were and decided to stay hidden and then sneak back in, acting like I’d been inside the house all along—I wasn’t ever supposed to leave my mother alone. The unlatched screen door was a problem. That door was always supposed to be kept locked. Otherwise it would stay stubbornly cracked open and flies would be everywhere, big fat metallic blue ones with loud buzzes that made you feel sick when you got them with the swatter—their heavy fall from the window onto the sill, the way they would lie there on their backs, their legs in the air, only half dead. But I’d just say I’d forgotten to latch it—it certainly wouldn’t be the first time.

I had only yesterday discovered access to this space under the porch, small and damp and fecund-smelling—cool, too; and in a climate like ours that was not to be undervalued. Mostly I liked how utterly private it was. In addition to my other burgeoning desires, I was beginning to crave privacy. Sometimes I sat at the edge of the bed in my room doing nothing but feeling the absence of interference.

I sucked at the back of my wrist for the salt and watched as Peacie started up the steps, thinking I might reach out, grab her ankle, and give it a yank, thinking of the spectacular fall I might cause, the black purse flying. I often wanted to hurt Peacie, because in my mind she wielded far too much power.

Peacie was still allowed to spank me, using a wooden mixing spoon. She was also allowed to determine which of my misdeeds deserved such punishment, and I believed this was wrong—only a parent should be allowed to do that. But my mother had decided long ago that some battles were worth fighting and some just weren’t—if Peacie said I needed a spanking, well, then, I needed a spanking. My mother made up for it later—a treat close to dinnertime, an extra half hour of television, a story from her girlhood, which I always loved—and in the meantime she kept a reliable caregiver. Others came and went; Peacie stayed. And stayed.

Once, when I was six years old and Peacie was sitting at the kitchen table taking her break, her shoes off and her feet up on another chair, I’d crossed my arms and leaned on the table to look closely into her eyes. I’d meant to pull her into a kinder regard for me, to effect an avalanche of regret on her part for her meanness, followed by a fervent resolution to do better by me. She had dragged me to revival meetings; I knew about sudden miracles. But there’d been no getting through to Peacie. She did not tremble and roll her eyes back in her head and then chuckle and pull me to her. Instead, she narrowed her eyes and said, “What you looking at?”

“Nothing,” I said. “You.”

“Get gone.” She picked a piece of tobacco off her tongue and flicked it into the ashtray. The ashtray was one of the few things belonging to my father that we still had; it featured black and red playing cards rimmed with gold. “Go find something entertain yourself.”

“But what?” I spoke quietly, my head hanging low. I felt sorry for myself, tragic. I longed for a red cape to fling around myself at this moment. I would cover half my face, and only my soulful eyes would peek out. I had my mother’s eyes, a blue so dark they were almost navy, fringed by thick black lashes. “What is there to do?”

“Crank up your voice box; I cain’t hear a word you saying.”

I straightened. “What should I do?”

“You need me to tell you? You ain’t got your own brain? Go on outside and make some friends. I ain’t never seen such a solitary child. I guess you just too good for everybody.”

I stared at my feet, bare and brown, full of calluses of which I was inordinately proud and that were thick enough to let me walk down hot sidewalks without wincing. We had no sidewalks in our neighborhood, but downtown was only a mile away and they had sidewalks. They had everything. A lunch counter at the drugstore that sold cherry Cokes served in glasses with silver metal holders and set out on white paper doilies. They had a department store, a movie house, and especially they had a five-and-dime, which sold things I desired to distraction: Parakeets. Board games. Headbands and barrettes and rhinestone engagement rings and Friendship Garden perfume. Models of palomino horses wearing little bridles and saddles. There were gold heart necklaces featuring your birthstone on which you could have your name engraved. White leather diaries that locked with a real key. Cork-backed drink coasters of which I was unaccountably fond featuring a black-and-gold abstract pattern of what looked like boomerangs.

Peacie dug in her purse for a new pack of Chesterfields, and she did not, as ever, offer me one of the butterscotch candies that were in plain sight there. The actual butterscotch wasn’t as yellow as the wrapper, but still.

“I don’t think I’m too good for anyone,” I said. “But nobody will play with me.”

Peacie pulled out a cigarette with her long fingers, lit it with a kitchen match, and blew the smoke out over my head. “Humph. And why do you suppose that is?”

“Because my mother is a third base.”

Peacie held still as a photo for one second. Then she took her feet off the chair and slowly leaned over so that her face was next to mine. I could smell the vanilla extract she dabbed behind her ears every morning; I could see the red etching of veins in her eyes. I thought she was going to tell me a secret or quietly laugh—the moment seemed full of a kind of mirthful restraint—and I grinned companionably. “She is,” I said, in an effort to prolong and enlarge the moment.

But I had misread Peacie completely, for she reached out to grab me, squeezing my arms tightly. “Don’t you never say that again. Don’t you never think it, neither!” Her voice was low and terrible. “If I wasn’t resting my aching feet, if I wasn’t on my well-deserved break, I would get right out this chair and introduce your mouth to a fresh bar of soap.” She let me go and put her feet back up on the chair. The ash was long on her cigarette; the smoke undulated upward, uncaring. Peacie would not break from staring at me; in a way, that was worse than the way she’d squeezed me.

I began to cry; I had called my mother a third base rather in the same way I would have called her a brunette. I didn’t know exactly what it meant. I knew only that the kids in my neighborhood had once called her that and that it seemed to be funny—it certainly made them laugh. Those kids were all older than I; I was the youngest by three years, so it was doubtful they’d have been interested in playing with me anyway. But they had had a good time calling my mother a third base that day; they had giggled and jostled one another and continued laughing as they walked away.

“You hurt me!” I told Peacie. “I’m telling my mother!”

“If you wake her up,” Peacie said, “I’ll wear you out like you ain’t never been wore out before.”

“I wish only Mrs. Gruder would come here because I hate you!” My voice cracked, betraying my intention to sound fierce. I walked away, headed for the comfort of the out-of-doors: the high, white clouds, the singing insects, the wildflowers that grew at the base of the telephone poles. Behind me, I heard Peacie say, “I like Mrs. Gruder, too! Um-hum, sure do. Mrs. Gruder, I like.”

Eleanor Gruder was our current nighttime caretaker, who stayed until ten every evening. She wasn’t mean, like Peacie could be, but she wasn’t very interesting, either. After she’d put my mother to bed and was waiting for her husband to come and get her, she’d sit on the sofa with her hands folded in her lap, staring out at nothing, a little smile on her face. At those times, she reminded me of Baby McPherson, the retarded girl who used to live in our neighborhood and spent her days sitting out on the top step of her front porch, smiling in the same vacant way, her underpants showing. I would sit in my pajamas waiting with Mrs. Gruder, sometimes reading, sometimes dozing, and then, after her husband pulled up outside the house and honked for her, she would remind me to turn out the porch light and lock the door. Always, I turned out the light—electricity was expensive. But I never locked the front door. If I needed to get out, it would have to be quickly.

Mrs. Gruder was probably in her sixties and to my mind ancient. She was a big, fat, strong woman who liked to comb my hair, which fell to my waist. She did not jerk and pull and mutter like Peacie; rather she was almost worshipful, and so gentle I fell into a kind of starey-eyed hypnosis. She was married to a German man named Otto who gave accordion lessons and would never meet your eye. I had once heard my mother wondering aloud to Peacie about where he came from and what in the world he was doing here.

Mrs. Gruder was kind, but she made me feel suffocated. She offered me chocolate hearts wrapped in gold foil that came all the way from Munich, but it was the dark, bitter chocolate that I did not like. She read books to me, but her voice was flat and lifeless and she did not make up anything extra, or ask questions about what I thought was going to happen, or dramatize using different voices. These were things my mother always did. Even Peacie would stand still against the doorjamb, dust rag in hand, to hear my mother read.

My mother had perfected speaking in coordination with the rising and falling action of her respirator. She could talk only on exhalation, but most people couldn’t tell the difference between it and normal speech. Also, she was able to come out of her “shell,” the chest-to-waist casing to which the ventilator hose was attached, for an hour or two at a time. At those times, she practiced what was called frog breathing, using a downward motion on her tongue to force bits of air into her lungs. Seeing my mother out of the shell always gave me a kind of jazzy thrill; she almost looked normal.

Now I crouched silently and watched Peacie’s slim ankles as she mounted the sagging steps, one, two, three. I reached out my hand but stopped short of grabbing her. Just before she opened the screen door, she said, “I seen you. Devil.”

From the Hardcover edition.

The sun was barely up when I crept downstairs. I had awakened early again, full of a pulsating need to get out and get things done, though if the truth be told, I was not fully certain what those things were. I had recently turned thirteen and was being yanked about by hormones that had me weeping one moment and yelling the next; rapturously practice-kissing the inside of my elbow one moment, then crossing the street to avoid boys the next. I alternated between periods of extreme confidence and bouts of quivering insecurity. Life was curiously exhausting but also exhilarating.

I longed for things I’d never wanted before: clothes that conferred upon the wearer inalienable status, makeup that apparently transformed not only the face but the soul. But mostly I wanted a kind of inner strength that would offer protection against the small-town injustices I had long endured, something that would let me take pride in myself as myself. I focused on making money, because I believed that despite what people said, money could buy happiness. I knew beyond knowing that this was the summer I would get that money. All I had to figure out was how.

I crept into the dining room and made sure my mother was sleeping soundly, then slipped out onto the front porch. I wanted to be alone to unravel my restlessness, to soothe myself by making plans for the day being born before me. I stretched, then stood with my hands on my hips to survey the street on this already hot July day. It was dead as usual, no activity seen inside or out of the tiny houses with their sagging porches, their dented mailboxes, their yards mostly gone to dust. I walked down the steps and started for a patch of dandelions growing against the side of the house. I would use them to brighten my desk, where today I would be writing a letter to Sandra Dee. I wrote often to movie stars, letting them know that I, too, was an actress and also a playwright, just in case they might be looking for someone.

I did not get back inside quickly enough, for I heard a car door slam and looked over to see Peacie, her skinny self walking slowly toward our house, swinging her big black purse. She was wearing a red-and-white polka-dot housedress, the great big polka dots that looked like poker chips, and blindingly white ankle socks with her black men’s shoes, and inside her purse was the flowered apron she’d put on as soon as she stepped inside. When she left, she’d carry that apron home in a brown paper bag to wash in her own automatic washing machine—she did not like our wringer model.

I ran under the porch, praying she hadn’t seen me, wishing I’d known her boyfriend, LaRue, was going to drop her off. If I’d known that, I’d have stayed in the house so that I could have run out and visited with him. LaRue often brought me presents: Moon Pies or Goo-Goo Clusters, Popsicle sticks for the little houses I liked to build, puppets he’d made from socks, and on one memorable occasion, a silver dollar he’d won shooting craps. He could balance a goober on the end of his nose and then flip it into his mouth. He was a highly imaginative dresser; he once wore a tie made from the Sunday comics, for example. He favored electric colors and had white bucks on which he’d drawn intricate designs in black ink. He cooked bacon with brown sugar, chili powder, and pecans—praline bacon, he called it—and it was delicious. He told jokes that I could understand. He drank coffee out of a saucer and made it look elegant.

LaRue tooted his horn to Peacie and drove off. I thought quickly about what my options were and decided to stay hidden and then sneak back in, acting like I’d been inside the house all along—I wasn’t ever supposed to leave my mother alone. The unlatched screen door was a problem. That door was always supposed to be kept locked. Otherwise it would stay stubbornly cracked open and flies would be everywhere, big fat metallic blue ones with loud buzzes that made you feel sick when you got them with the swatter—their heavy fall from the window onto the sill, the way they would lie there on their backs, their legs in the air, only half dead. But I’d just say I’d forgotten to latch it—it certainly wouldn’t be the first time.

I had only yesterday discovered access to this space under the porch, small and damp and fecund-smelling—cool, too; and in a climate like ours that was not to be undervalued. Mostly I liked how utterly private it was. In addition to my other burgeoning desires, I was beginning to crave privacy. Sometimes I sat at the edge of the bed in my room doing nothing but feeling the absence of interference.

I sucked at the back of my wrist for the salt and watched as Peacie started up the steps, thinking I might reach out, grab her ankle, and give it a yank, thinking of the spectacular fall I might cause, the black purse flying. I often wanted to hurt Peacie, because in my mind she wielded far too much power.

Peacie was still allowed to spank me, using a wooden mixing spoon. She was also allowed to determine which of my misdeeds deserved such punishment, and I believed this was wrong—only a parent should be allowed to do that. But my mother had decided long ago that some battles were worth fighting and some just weren’t—if Peacie said I needed a spanking, well, then, I needed a spanking. My mother made up for it later—a treat close to dinnertime, an extra half hour of television, a story from her girlhood, which I always loved—and in the meantime she kept a reliable caregiver. Others came and went; Peacie stayed. And stayed.

Once, when I was six years old and Peacie was sitting at the kitchen table taking her break, her shoes off and her feet up on another chair, I’d crossed my arms and leaned on the table to look closely into her eyes. I’d meant to pull her into a kinder regard for me, to effect an avalanche of regret on her part for her meanness, followed by a fervent resolution to do better by me. She had dragged me to revival meetings; I knew about sudden miracles. But there’d been no getting through to Peacie. She did not tremble and roll her eyes back in her head and then chuckle and pull me to her. Instead, she narrowed her eyes and said, “What you looking at?”

“Nothing,” I said. “You.”

“Get gone.” She picked a piece of tobacco off her tongue and flicked it into the ashtray. The ashtray was one of the few things belonging to my father that we still had; it featured black and red playing cards rimmed with gold. “Go find something entertain yourself.”

“But what?” I spoke quietly, my head hanging low. I felt sorry for myself, tragic. I longed for a red cape to fling around myself at this moment. I would cover half my face, and only my soulful eyes would peek out. I had my mother’s eyes, a blue so dark they were almost navy, fringed by thick black lashes. “What is there to do?”

“Crank up your voice box; I cain’t hear a word you saying.”

I straightened. “What should I do?”

“You need me to tell you? You ain’t got your own brain? Go on outside and make some friends. I ain’t never seen such a solitary child. I guess you just too good for everybody.”

I stared at my feet, bare and brown, full of calluses of which I was inordinately proud and that were thick enough to let me walk down hot sidewalks without wincing. We had no sidewalks in our neighborhood, but downtown was only a mile away and they had sidewalks. They had everything. A lunch counter at the drugstore that sold cherry Cokes served in glasses with silver metal holders and set out on white paper doilies. They had a department store, a movie house, and especially they had a five-and-dime, which sold things I desired to distraction: Parakeets. Board games. Headbands and barrettes and rhinestone engagement rings and Friendship Garden perfume. Models of palomino horses wearing little bridles and saddles. There were gold heart necklaces featuring your birthstone on which you could have your name engraved. White leather diaries that locked with a real key. Cork-backed drink coasters of which I was unaccountably fond featuring a black-and-gold abstract pattern of what looked like boomerangs.

Peacie dug in her purse for a new pack of Chesterfields, and she did not, as ever, offer me one of the butterscotch candies that were in plain sight there. The actual butterscotch wasn’t as yellow as the wrapper, but still.

“I don’t think I’m too good for anyone,” I said. “But nobody will play with me.”

Peacie pulled out a cigarette with her long fingers, lit it with a kitchen match, and blew the smoke out over my head. “Humph. And why do you suppose that is?”

“Because my mother is a third base.”

Peacie held still as a photo for one second. Then she took her feet off the chair and slowly leaned over so that her face was next to mine. I could smell the vanilla extract she dabbed behind her ears every morning; I could see the red etching of veins in her eyes. I thought she was going to tell me a secret or quietly laugh—the moment seemed full of a kind of mirthful restraint—and I grinned companionably. “She is,” I said, in an effort to prolong and enlarge the moment.

But I had misread Peacie completely, for she reached out to grab me, squeezing my arms tightly. “Don’t you never say that again. Don’t you never think it, neither!” Her voice was low and terrible. “If I wasn’t resting my aching feet, if I wasn’t on my well-deserved break, I would get right out this chair and introduce your mouth to a fresh bar of soap.” She let me go and put her feet back up on the chair. The ash was long on her cigarette; the smoke undulated upward, uncaring. Peacie would not break from staring at me; in a way, that was worse than the way she’d squeezed me.

I began to cry; I had called my mother a third base rather in the same way I would have called her a brunette. I didn’t know exactly what it meant. I knew only that the kids in my neighborhood had once called her that and that it seemed to be funny—it certainly made them laugh. Those kids were all older than I; I was the youngest by three years, so it was doubtful they’d have been interested in playing with me anyway. But they had had a good time calling my mother a third base that day; they had giggled and jostled one another and continued laughing as they walked away.

“You hurt me!” I told Peacie. “I’m telling my mother!”

“If you wake her up,” Peacie said, “I’ll wear you out like you ain’t never been wore out before.”

“I wish only Mrs. Gruder would come here because I hate you!” My voice cracked, betraying my intention to sound fierce. I walked away, headed for the comfort of the out-of-doors: the high, white clouds, the singing insects, the wildflowers that grew at the base of the telephone poles. Behind me, I heard Peacie say, “I like Mrs. Gruder, too! Um-hum, sure do. Mrs. Gruder, I like.”

Eleanor Gruder was our current nighttime caretaker, who stayed until ten every evening. She wasn’t mean, like Peacie could be, but she wasn’t very interesting, either. After she’d put my mother to bed and was waiting for her husband to come and get her, she’d sit on the sofa with her hands folded in her lap, staring out at nothing, a little smile on her face. At those times, she reminded me of Baby McPherson, the retarded girl who used to live in our neighborhood and spent her days sitting out on the top step of her front porch, smiling in the same vacant way, her underpants showing. I would sit in my pajamas waiting with Mrs. Gruder, sometimes reading, sometimes dozing, and then, after her husband pulled up outside the house and honked for her, she would remind me to turn out the porch light and lock the door. Always, I turned out the light—electricity was expensive. But I never locked the front door. If I needed to get out, it would have to be quickly.

Mrs. Gruder was probably in her sixties and to my mind ancient. She was a big, fat, strong woman who liked to comb my hair, which fell to my waist. She did not jerk and pull and mutter like Peacie; rather she was almost worshipful, and so gentle I fell into a kind of starey-eyed hypnosis. She was married to a German man named Otto who gave accordion lessons and would never meet your eye. I had once heard my mother wondering aloud to Peacie about where he came from and what in the world he was doing here.

Mrs. Gruder was kind, but she made me feel suffocated. She offered me chocolate hearts wrapped in gold foil that came all the way from Munich, but it was the dark, bitter chocolate that I did not like. She read books to me, but her voice was flat and lifeless and she did not make up anything extra, or ask questions about what I thought was going to happen, or dramatize using different voices. These were things my mother always did. Even Peacie would stand still against the doorjamb, dust rag in hand, to hear my mother read.

My mother had perfected speaking in coordination with the rising and falling action of her respirator. She could talk only on exhalation, but most people couldn’t tell the difference between it and normal speech. Also, she was able to come out of her “shell,” the chest-to-waist casing to which the ventilator hose was attached, for an hour or two at a time. At those times, she practiced what was called frog breathing, using a downward motion on her tongue to force bits of air into her lungs. Seeing my mother out of the shell always gave me a kind of jazzy thrill; she almost looked normal.

Now I crouched silently and watched Peacie’s slim ankles as she mounted the sagging steps, one, two, three. I reached out my hand but stopped short of grabbing her. Just before she opened the screen door, she said, “I seen you. Devil.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

Elizabeth Berg is the New York Times bestselling author of many novels, including We Are All Welcome Here, The Year of Pleasures, The Art of Mending, Say When, True to Form, Never Change, and Open House, which was an Oprah’s Book Club selection in 2000. Durable Goods and Joy School were selected as ALA Best Books of the Year, and Talk Before Sleep was short-listed for the ABBY Award in 1996. The winner of the 1997 New England Booksellers Award for her body of work, Berg is also the author of a nonfiction work, Escaping into the Open: The Art of Writing True. She lives in Chicago.

To schedule a speaking engagement, please contact American Program Bureau at www.apbspeakers.com

From the Hardcover edition.

To schedule a speaking engagement, please contact American Program Bureau at www.apbspeakers.com

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The bestselling author of "The Art of Mending" and "The Year of Pleasures" follows the story of three women in 1965, Tupelo, Mississippi, each struggling against overwhelming odds for her own kind of freedom.