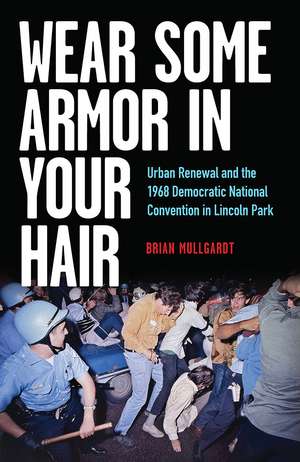

Wear Some Armor in Your Hair: Urban Renewal and the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Lincoln Park

Autor Brian Mullgardten Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 mai 2024

In August of 1968, approximately 7,000 people protested the Vietnam War against the backdrop of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. This highly televised event began peacefully but quickly turned into what was later termed a “police riot.” Brian Mullgardt’s investigation of this event and the preceding tensions shines a light on the ministers, Yippies, and community members who showed up and stood together against the brutality of the police. Charting a complex social history, Wear Some Armor in Your Hair brings together Chicago history, the 1960s, and urbanization, focusing not on the national leaders, but on the grassroots activists of the time.

Beginning in 1955, two competing visions of urban renewal existed, and the groups that propounded each clashed publicly, but peacefully. One group, linked to city hall, envisioned a future Lincoln Park that paid lip service to diversity but actually included very little. The other group, the North Side Cooperative Ministry, offered a different vision of Lincoln Park that was much more diverse in terms of class and race. When the Yippies announced anti-war protests for the summer of ‘68, the North Side Cooperative Ministry played an instrumental role. Ultimately, the violence of that week altered community relations and the forces of gentrification won out.

Mullgardt’s focus on the activists and community members of Lincoln Park, a neighborhood at the nexus of national trends, broadens the scope of understanding around a pivotal and monumental chapter of our history. The story of Lincoln Park, Chicago, is in many ways the story of 1960s activism writ small, and in other ways challenges us to view national trends differently.

Preț: 233.05 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 350

Preț estimativ în valută:

44.60€ • 48.43$ • 37.46£

44.60€ • 48.43$ • 37.46£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809339358

ISBN-10: 0809339358

Pagini: 274

Ilustrații: 12

Dimensiuni: 152 x 235 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

ISBN-10: 0809339358

Pagini: 274

Ilustrații: 12

Dimensiuni: 152 x 235 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Notă biografică

Brian Mullgardt is a professor of history at Millikin University who specializes in US history in the Cold War era, with an emphasis on social activism during the “Long Sixties” (1955-1975). He has served as the vice president of the Macon County Historical Society and Museum and on the board of directors for the Illinois State Historical Society. He has published in several journals, including the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society and the Journal of Illinois History.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

On Wednesday night, August 28th, 1968, some 90 million television viewers watched Chicago Police Department officers attack demonstrators in a moment now infamous in the history of the 1960s. It began when approximately 7,000 people protesting both the Vietnam War and the Democratic Party marched to Chicago’s downtown at Michigan Avenue and Balbo Street. These demonstrators, some chanting “Fuck LBJ,” “Hell no, we won’t go,” and “Pigs eat shit,” stood outside of the Hilton Hotel opposite helmet clad policemen gripping menacing batons. Some demonstrators threw bottles and rocks at officers who were then ordered to clear the crowd. Chaos followed. While some policemen acted calmly and responsibly others, some chanting “Kill, kill, kill,” beat people.” Others sprayed mace. Policemen dragged protesters into paddy wagons, sometimes clubbing their captives as they slammed them into the vans. Some protesters fought back, and others chanted, “the whole world is watching.” The broadcast melee lasted only about twenty minutes, but violence continued for hours.

The scene inside the Convention, also televised, is just as notorious. While barbed wire covered army jeeps patrolled nearby streets as part of an absurd defense strategy, Mayor Richard J. Daley shouted at Senator Abraham Ribicoff inside the hall. Democrats bickered and screamed at each other, one angrily addressing police brutality outside. The same violence transpiring on the street found its way inside the Convention and nearby Hilton hotel as officers attacked anyone they saw fit to pummel.

What started out as a week-long protest in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, several miles north of the Convention, had turned into days of skirmishes, sometimes violent, between protester and police officer. Now, the nation watched what the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, the group charged with investigating the bloodshed, labeled a “police riot.” In its wake, Richard Nixon called for “law and order” in the streets, an emphasis that arguably aided his election as president. For those active in “the Movement,” that spectrum of civil rights, antiwar, countercultural, and leftist activism, Chicago was proof positive that Americans lived in a repressive police state where anyone advocating change had to be even more suspicious of authorities and concerned for their personal safety.

The incident at Michigan and Balbo, the drama inside the Convention hall, and the antics of the Youth International Party (Yippies) in the months and days before have, thanks in part to vivid television coverage, been packaged together as a pivotal moment in 1960s history, one complete with colorful characters both fiery and whimsical, rising tension, and a violent climax. In the traditional telling Yippie leaders and Richard Daley took center stage while those beaten on the streets played supporting roles. However, focusing on the twenty-minute televised “riot” fails to place all of the key historical actors in frame and offers a limited view of events. There was another important drama in Chicago that week that better informs us about not only the city, but the nation, in the 1960s. Within the broad spectacle of Convention week a very local protest transpired, largely off camera, one that mirrored national disagreements about the power of the state versus the rights of its citizens that brought to a head long-simmering problems on the north side of Chicago. Pulling the camera back and examining more than just Wednesday night provides the full picture.

On Tuesday, August 27th, at approximately 11 pm, ministers carrying an eight-foot cross entered Lincoln Park. This was in response to increasing police violence over the previous two days and about enforcement of the rarely imposed 11 pm curfew in the park. About two thousand people watched as the ministers began a religious service. Local clergymen spoke, others made public statements and sang hymns, but many present were mainly waiting for the Chicago police to again clear the park. While officers prepared to advance and special mace spraying trucks moved into position, some demonstrators argued loudly for violence in the streets. Others were adamant they peacefully stand their ground. Protesters scrambled to build a barricade of picnic tables and trashcans between the ministers and approaching officers. Clergymen advised those who would listen to “sit or split”: either leave now or sit down, lock arms, and remain calm. Then, demonstrators sat and tied handkerchiefs across their faces to combat the whitish chemical fog now bursting out of shells and spewing from trucks. As the gas rolled in shortly after 12:30, one minister vowed, “This is our Park. We will not be moved.”

Gas-mask clad officers then entered the park swinging clubs, knocking one minister unconscious. Stinging mace drifted in the air. Nightsticks crashed down on muscle and bone. Scared and confused demonstrators scrambled to find safety. Protesters fired back with rocks and bottles as the gas curled its way into the surrounding neighborhood. The police repeated that the area was to be cleared, but brick and rock missiles pelted their cars as they chased down demonstrators. That night alone, Chicago police officers arrested some 160 persons, while seven policemen and over sixty demonstrators experienced injury. Abe Peck, hippie activist and editor of the Chicago underground paper Seed, referred to the conflict Tuesday night as “the elemental struggle” for local countercultural members. The whole world may have watched on Wednesday, but few Americans saw this pivotal moment for Lincoln Park residents on Tuesday, an instant with many layers that encapsulated late 60s America.

This local protest involved more than Yippies, Daley, and violence. In a decade when the American clergy debated its relevance, ministers led the protest in Lincoln Park. In an era when the counterculture grew, hips helped plan Chicago’s demonstration alongside “average” area residents making this a grassroots protest in a time when “average” people joined together in the south and north to combat entrenched powers. In an era when cities underwent urban renewal programs that displaced many in the name of progress, Lincoln Park was home to residents advancing an urban renewal plan.

This study examines how, on Chicago’s north side, urban renewal and gentrification, liberalism, the counterculture, police violence, the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and grassroots activism molded the development of a neighborhood and the city in the postwar years. Early top-down works on the history of the 1960s chronicle Civil Rights, anti-war and New Left leaders. Scholars later shifted the focus from national to local leadership on college campuses and in student organizations. This study answers the call by historians to analyze 1960s at the grassroots by examining how ordinary citizens molded urban renewal, gentrification and the events of August of 1968. Wear Some Armor in Your Hair also contributes to Chicago history by placing Lincoln Park within the history of postwar development of the city.

The story of the Democratic National Convention of 1968 sits within the larger story of the development of the Lincoln Park neighborhood from 1948 to 1974, an area that hosted the North Side’s first large-scale urban renewal project. After WWII, ideas about the neighborhood’s identity were as varied as its architecture. Two visions of community emerged before August, 1968. White liberals belonging to the area’s neighborhood organizations united under the umbrella group the Lincoln Park Conservation Association (LPCA) and began to advance their dream for the area in the 1950s. From day one they fused their group to Chicago’s power structure, working with city officials to have the area declared eligible for urban renewal aid and obtaining funds from the federal government, the state of Illinois and the city to further their vision, one that claimed to embrace diversity. By the 1960s some white Americans avoided directly addressing race as an issue then they discussed neighborhood change. Instead, they offered up “individual rights” and other coded language in their objections to governmental oversight of development. As in other parts of the nation, white liberals in Lincoln Park did not openly discriminate in their plans, but instead objected to high-rise and public housing—edifices rather than people. Lincoln “Parkers” of the Democratic 43rd ward did not overtly seek to exclude non-white and poor residents from the area but wanted to cushion themselves in a secure zone, pursuing a kind of domestic containment.

Scholars have examined and treated urban renewal and gentrification as separate subjects. For example, one anthropologist defines gentrification as:

“…an economic and social process whereby private capital (real estate firms, developers) and individual homeowners and renters reinvest in fiscally neglected neighborhoods through housing rehabilitation, loft conversions, and the construction of new housing stock. Unlike urban renewal (italics mine), gentrification is a gradual process, occurring one building or block at a time, slowly reconfiguring the neighborhood landscape of consumption and residence by displacing poor and working-class residents unable to afford to live in ‘revitalized’ neighborhoods with rising rents, property taxes, and new businesses catering to an upscale clientele.”

One historian notes that gentrifiers he chronicled were “veterans in the fight against urban renewal.” And yet, dividing and easily defining the two can be challenging. Two scholars offer, “When historians refer to ‘urban renewal,’ they are not describing one singular policy. Rather, they are describing a host of programs and policies that wrought a series of radical interventions on the urban built environment.” Another refers to both “gentrifier” and “gentrification” as “chaotic conceptions.”

In urban renewal histories, generally, government and residents native to an area work together to affect change, while in gentrification studies citizens from outside a neighborhood descend on and alter it. Both stories of renewal and gentrification, however, often end up at the same conclusion: the displacement of poorer residents and/or persons of color.

[end of excerpt]

On Wednesday night, August 28th, 1968, some 90 million television viewers watched Chicago Police Department officers attack demonstrators in a moment now infamous in the history of the 1960s. It began when approximately 7,000 people protesting both the Vietnam War and the Democratic Party marched to Chicago’s downtown at Michigan Avenue and Balbo Street. These demonstrators, some chanting “Fuck LBJ,” “Hell no, we won’t go,” and “Pigs eat shit,” stood outside of the Hilton Hotel opposite helmet clad policemen gripping menacing batons. Some demonstrators threw bottles and rocks at officers who were then ordered to clear the crowd. Chaos followed. While some policemen acted calmly and responsibly others, some chanting “Kill, kill, kill,” beat people.” Others sprayed mace. Policemen dragged protesters into paddy wagons, sometimes clubbing their captives as they slammed them into the vans. Some protesters fought back, and others chanted, “the whole world is watching.” The broadcast melee lasted only about twenty minutes, but violence continued for hours.

The scene inside the Convention, also televised, is just as notorious. While barbed wire covered army jeeps patrolled nearby streets as part of an absurd defense strategy, Mayor Richard J. Daley shouted at Senator Abraham Ribicoff inside the hall. Democrats bickered and screamed at each other, one angrily addressing police brutality outside. The same violence transpiring on the street found its way inside the Convention and nearby Hilton hotel as officers attacked anyone they saw fit to pummel.

What started out as a week-long protest in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, several miles north of the Convention, had turned into days of skirmishes, sometimes violent, between protester and police officer. Now, the nation watched what the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, the group charged with investigating the bloodshed, labeled a “police riot.” In its wake, Richard Nixon called for “law and order” in the streets, an emphasis that arguably aided his election as president. For those active in “the Movement,” that spectrum of civil rights, antiwar, countercultural, and leftist activism, Chicago was proof positive that Americans lived in a repressive police state where anyone advocating change had to be even more suspicious of authorities and concerned for their personal safety.

The incident at Michigan and Balbo, the drama inside the Convention hall, and the antics of the Youth International Party (Yippies) in the months and days before have, thanks in part to vivid television coverage, been packaged together as a pivotal moment in 1960s history, one complete with colorful characters both fiery and whimsical, rising tension, and a violent climax. In the traditional telling Yippie leaders and Richard Daley took center stage while those beaten on the streets played supporting roles. However, focusing on the twenty-minute televised “riot” fails to place all of the key historical actors in frame and offers a limited view of events. There was another important drama in Chicago that week that better informs us about not only the city, but the nation, in the 1960s. Within the broad spectacle of Convention week a very local protest transpired, largely off camera, one that mirrored national disagreements about the power of the state versus the rights of its citizens that brought to a head long-simmering problems on the north side of Chicago. Pulling the camera back and examining more than just Wednesday night provides the full picture.

On Tuesday, August 27th, at approximately 11 pm, ministers carrying an eight-foot cross entered Lincoln Park. This was in response to increasing police violence over the previous two days and about enforcement of the rarely imposed 11 pm curfew in the park. About two thousand people watched as the ministers began a religious service. Local clergymen spoke, others made public statements and sang hymns, but many present were mainly waiting for the Chicago police to again clear the park. While officers prepared to advance and special mace spraying trucks moved into position, some demonstrators argued loudly for violence in the streets. Others were adamant they peacefully stand their ground. Protesters scrambled to build a barricade of picnic tables and trashcans between the ministers and approaching officers. Clergymen advised those who would listen to “sit or split”: either leave now or sit down, lock arms, and remain calm. Then, demonstrators sat and tied handkerchiefs across their faces to combat the whitish chemical fog now bursting out of shells and spewing from trucks. As the gas rolled in shortly after 12:30, one minister vowed, “This is our Park. We will not be moved.”

Gas-mask clad officers then entered the park swinging clubs, knocking one minister unconscious. Stinging mace drifted in the air. Nightsticks crashed down on muscle and bone. Scared and confused demonstrators scrambled to find safety. Protesters fired back with rocks and bottles as the gas curled its way into the surrounding neighborhood. The police repeated that the area was to be cleared, but brick and rock missiles pelted their cars as they chased down demonstrators. That night alone, Chicago police officers arrested some 160 persons, while seven policemen and over sixty demonstrators experienced injury. Abe Peck, hippie activist and editor of the Chicago underground paper Seed, referred to the conflict Tuesday night as “the elemental struggle” for local countercultural members. The whole world may have watched on Wednesday, but few Americans saw this pivotal moment for Lincoln Park residents on Tuesday, an instant with many layers that encapsulated late 60s America.

This local protest involved more than Yippies, Daley, and violence. In a decade when the American clergy debated its relevance, ministers led the protest in Lincoln Park. In an era when the counterculture grew, hips helped plan Chicago’s demonstration alongside “average” area residents making this a grassroots protest in a time when “average” people joined together in the south and north to combat entrenched powers. In an era when cities underwent urban renewal programs that displaced many in the name of progress, Lincoln Park was home to residents advancing an urban renewal plan.

This study examines how, on Chicago’s north side, urban renewal and gentrification, liberalism, the counterculture, police violence, the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and grassroots activism molded the development of a neighborhood and the city in the postwar years. Early top-down works on the history of the 1960s chronicle Civil Rights, anti-war and New Left leaders. Scholars later shifted the focus from national to local leadership on college campuses and in student organizations. This study answers the call by historians to analyze 1960s at the grassroots by examining how ordinary citizens molded urban renewal, gentrification and the events of August of 1968. Wear Some Armor in Your Hair also contributes to Chicago history by placing Lincoln Park within the history of postwar development of the city.

The story of the Democratic National Convention of 1968 sits within the larger story of the development of the Lincoln Park neighborhood from 1948 to 1974, an area that hosted the North Side’s first large-scale urban renewal project. After WWII, ideas about the neighborhood’s identity were as varied as its architecture. Two visions of community emerged before August, 1968. White liberals belonging to the area’s neighborhood organizations united under the umbrella group the Lincoln Park Conservation Association (LPCA) and began to advance their dream for the area in the 1950s. From day one they fused their group to Chicago’s power structure, working with city officials to have the area declared eligible for urban renewal aid and obtaining funds from the federal government, the state of Illinois and the city to further their vision, one that claimed to embrace diversity. By the 1960s some white Americans avoided directly addressing race as an issue then they discussed neighborhood change. Instead, they offered up “individual rights” and other coded language in their objections to governmental oversight of development. As in other parts of the nation, white liberals in Lincoln Park did not openly discriminate in their plans, but instead objected to high-rise and public housing—edifices rather than people. Lincoln “Parkers” of the Democratic 43rd ward did not overtly seek to exclude non-white and poor residents from the area but wanted to cushion themselves in a secure zone, pursuing a kind of domestic containment.

Scholars have examined and treated urban renewal and gentrification as separate subjects. For example, one anthropologist defines gentrification as:

“…an economic and social process whereby private capital (real estate firms, developers) and individual homeowners and renters reinvest in fiscally neglected neighborhoods through housing rehabilitation, loft conversions, and the construction of new housing stock. Unlike urban renewal (italics mine), gentrification is a gradual process, occurring one building or block at a time, slowly reconfiguring the neighborhood landscape of consumption and residence by displacing poor and working-class residents unable to afford to live in ‘revitalized’ neighborhoods with rising rents, property taxes, and new businesses catering to an upscale clientele.”

One historian notes that gentrifiers he chronicled were “veterans in the fight against urban renewal.” And yet, dividing and easily defining the two can be challenging. Two scholars offer, “When historians refer to ‘urban renewal,’ they are not describing one singular policy. Rather, they are describing a host of programs and policies that wrought a series of radical interventions on the urban built environment.” Another refers to both “gentrifier” and “gentrification” as “chaotic conceptions.”

In urban renewal histories, generally, government and residents native to an area work together to affect change, while in gentrification studies citizens from outside a neighborhood descend on and alter it. Both stories of renewal and gentrification, however, often end up at the same conclusion: the displacement of poorer residents and/or persons of color.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

List of Acronyms

Introduction

1. Diversity and Renewal

2. Renewal and Inclusion

3. The Counterculture

4. Wear Some Armor in Your Hair

5. 1969

6. Confrontation and Gentrification

Notes

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

List of Acronyms

Introduction

1. Diversity and Renewal

2. Renewal and Inclusion

3. The Counterculture

4. Wear Some Armor in Your Hair

5. 1969

6. Confrontation and Gentrification

Notes

Bibliography

Recenzii

“With great precision, clarity, and ample evidence, Mullgardt demonstrates how a particular constellation of forces—liberalism, urban renewal, counterculture, local activists, and clergy—shaped Chicago’s North side before and after the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Scholars of urban history and students of the sixties will find this book an important and fascinating read.”—Damon R. Bach, author of The American Counterculture: A History of Hippies and Cultural Dissidents

“Views of the 1960s counterculture are too often simplified and centered on the coasts, with images of dancing flower children and rebellious youth. Mullgardt offers a valuable corrective, focusing not on the leaders of the protests, but on local Chicago activists, including clergy and people of color. The Yippies who came to Chicago found that there was already a movement for equality and justice happening here—and it continued after the DNC circus left town.”—Mary Wisniewski, author of Algren: A Life

“This is an ambitious work that weaves several heretofore separate stories into a new account of both Lincoln Park and the 1968 Democratic Convention. In doing so, Mullgardt adds to our understanding of both urban renewal and gentrification, as well as to their fascinating connections to 1960s counterculture and radical politics. Through the lens of the Lincoln Park neighborhood in 1960s, the book explores larger issues including civil rights, the counterculture, and radical politics that played out during the Democratic Convention in August 1968. In doing so, it offers a nuanced and grounded view of national events, as well as showing the ways that Lincoln Park leaders, issues, and organizations shaped broader events. The real power of this book is that it does not stay in one academic lane, but pulls threads from multiple fields to tell the story of gentrifying Lincoln Park and the 1968 Convention.”—Ann Durkin Keating, coeditor, Encyclopedia of Chicago

“Views of the 1960s counterculture are too often simplified and centered on the coasts, with images of dancing flower children and rebellious youth. Mullgardt offers a valuable corrective, focusing not on the leaders of the protests, but on local Chicago activists, including clergy and people of color. The Yippies who came to Chicago found that there was already a movement for equality and justice happening here—and it continued after the DNC circus left town.”—Mary Wisniewski, author of Algren: A Life

“This is an ambitious work that weaves several heretofore separate stories into a new account of both Lincoln Park and the 1968 Democratic Convention. In doing so, Mullgardt adds to our understanding of both urban renewal and gentrification, as well as to their fascinating connections to 1960s counterculture and radical politics. Through the lens of the Lincoln Park neighborhood in 1960s, the book explores larger issues including civil rights, the counterculture, and radical politics that played out during the Democratic Convention in August 1968. In doing so, it offers a nuanced and grounded view of national events, as well as showing the ways that Lincoln Park leaders, issues, and organizations shaped broader events. The real power of this book is that it does not stay in one academic lane, but pulls threads from multiple fields to tell the story of gentrifying Lincoln Park and the 1968 Convention.”—Ann Durkin Keating, coeditor, Encyclopedia of Chicago

Descriere

The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago began peacefully but quickly turned into what was later termed a “police riot.” Brian Mullgardt’s investigation of this event and the preceding tensions charts a complex social history that brings together Chicago history, the 1960s, and urbanization, focusing not on the national leaders, but on the grassroots activists of the time.