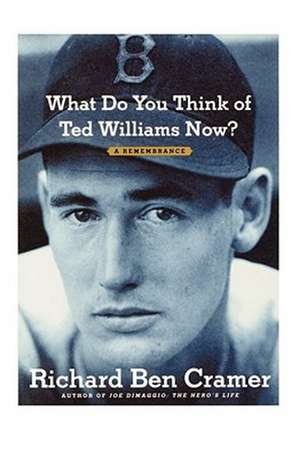

What Do You Think of Ted Williams Now?: A Remembrance

Autor Richard Ben Crameren Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 mai 2011

When legendary Red Sox hitter Ted Williams died on July 5, 2002, newspapers reviewed the stats, compared him to other legends of the game, and declared him the greatest hitter who ever lived.

In 1986, Richard Ben Cramer spent months on a profile of Ted Williams, and the result was the Esquire article that has been acclaimed ever since as one of the finest pieces of sports reporting ever written.

Given special acknowledgment in The Best American Sportswriting of the Century and adapted for a coffee-table book called Ted Williams: The Seasons of the Kid, the original piece is now available in this special edition, with new material about Williams's later years.

While his decades after Fenway Park were out of the spotlight -- the way Ted preferred it -- they were arguably his richest, as he loved and inspired his family, his fans, the players, and the game itself. This is a remembrance for the ages.

Preț: 62.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 94

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.02€ • 12.86$ • 10.03£

12.02€ • 12.86$ • 10.03£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781451643404

ISBN-10: 1451643403

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1451643403

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Extras

Ted Williams

August 30, 1918

July 5, 2002

Even in the last years of his life -- even as America and the sub-nation of baseball hungrily re-embraced him -- I knew I could provoke surprise (and more than a few arguments) when I said that Ted Williams was not just a great ballplayer, he was a great man.

Reputation dies hard in the baseball nation, and in the larger industry of American iconography. Even at the close of the century, forty years after he'd left the field, there still attached to Ted a lingering whiff of bile from the days when he spat toward booing Fenway fans. And there were heartbroken hundreds who'd freshen that scent with their stories: how he was rude to them when they tried to interrupt him for an autograph or a grip-and-grin photo. (The thousands who got their signatures or snapshots found that unremarkable.)

In the northeast corner of the nation, there were still thousands who blamed Ted for never hauling the Red Sox to World Series triumph. (Someone must bear blame for decades of disappointment when their own rooting love was so piquant and pure.)...Around New York more thousands still resented Ted -- and had to reduce him -- for contesting with Joe DiMaggio for the title of Greatest of the Golden Age. They insisted that Ted never won anything (and reviled him, in short, for never being a Yankee)....And westward through the baseball nation -- even where the game, not a team, was the passion -- historians huffed about his merit (or lack thereof) in left field; the stat-priests essayed talmudic arguments about how many runs he failed to drive in (because he'd never swing at a pitch out of the strike zone); and millions of kindly, casual fans (even those who'd agree Ted was the greatest hitter) seemed comfortable if they could tuck him into some pigeonhole -- most often as a minor freak of nature: "Wasn't it true his eyes were twice as good as a normal man's?"...

They missed the point. It wasn't his eyes, it was the avid mind behind them, and the great heart below. Ted was the greatest hitter because he knew more about that job than anyone else. He studied it relentlessly. If you knew anything about it, he wanted to know it -- and RIGHT NOW! He ripped the art into knowable shards, which he then could teach with clarity, with conviction (something he was never short on), and with surprising patience and generosity. That's how he was about anything he loved. It was the love that drove him.

Fans couldn't take their eyes off Ted because they could feel his heart yearning with theirs. His want -- in his guilelessness he never could hide it -- was ratification for theirs. If the coin of his love flipped, and all they could see was rage -- still, it was honest currency, for there was no counterfeit in him. Love and rage make a warrior...and in the inarticulate gush of words that attended his death in 2002, the particularity of our loss was lost. There were endless rehearsals of his stats, and comparisons to Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, DiMaggio (of course), Hornsby, Wagner, Mays, Aaron, Barry Bonds...there was solemn reference to his service as a pilot in two wars, and speculation on where Ted might have protruded from the great number-pile if he hadn't lost those five prime years...there were interviews that seemed intent on reassuring fans that Ted was a nice guy. But he wasn't a nice guy. He was an impossibly high-wide-and-handsome, outsized, obstreperous major-league overload of a man who dominated dugouts and made grand any ground he played on -- because his great warrior heart could fill ten ballparks. And latterly (here was our loss writ large), he was our link to that time before baseball became just another arm of the entertainment cartel.

I met Ted in 1986, in service to the entertainment biz: the editors of Esquire were scrabbling for features to fit between the ads in an issue the size of a small phone book, entitled "The American Man." And they had the inchoate sense that, somehow, Ted was The American Man. (Problem was, he was a Famously Uncooperative American Man.) So they sent me to meet him. The written product of that encounter -- you'll see it in the pages that follow -- they ran under the heading: "Mr. Everything."

But I want to spend a minute here on the unwritten product -- unwritten because it didn't come clear for years after that publication -- what I learned from that meeting with Ted. The big thing was he helped me -- when he didn't have to -- helped me to see him, understand him, feel with him, and have him in my life. He gave of himself with generosity that he knew would be unrecompensed -- and with a fearlessness about his own size that was truly exemplary -- that would change my life.

Why didn't I write that?...Well, I wrote what I understood. Anyway, I wasn't the story. But, truth be told, it was hard to tell he was helping me, when I'd leave his house all bruised from his insults and half-deaf from his latest loud evidence of how much he knew and I didn't. If I had to sum up what he showed me, it was the difference between politesse -- Ted wasn't big on that -- and what was the large, true-blue, right thing to do.

Here's one small example. In those days, I was a cigarette smoker, which horrified Ted. Not only had he never smoked, he was way ahead of his time in allowing no smoke around him. So if the urge struck, I'd idle through a Camel in his backyard, with its view of the mangroves and the Florida Bay. One day, he was shouting in his living room when the phone rang -- he started cursing. (He hated the phone, too.) I only spoke to calm him. "Go ahead, Ted, take the call. I'm goin' out back to have a smoke."

"That smokin'," he growled, "that's the WORST goddamn thing you could do. HOW OLD ARE YOU?"

"Thirty-five."

"WHEN I WAS YOUR AGE, I COULD PULL A TREE OUTA THE GROUND!...AN' LOOK AT YOU -- LOSIN' YER HAIR!"

It was later, too, I understood this was pattern with Ted. He had to rough up the people he meant to help. If you asked him about this, he would answer with a purely tactical truth -- in situations where you mean to teach, it's useful to keep clear who knows and who doesn't. But strategically this syndrome was a disaster: as a husband, father, and subject for the sporting press, it brought him unending grief. Ted's old friends couldn't explain it, but they all knew the pattern -- and richly enjoyed it. When the old-timers gathered to teach at spring training camp, Bobby Doerr, the erstwhile Sox second baseman, used to grab some young, eager Boston prospect and counsel him to go tell Ted how he meant to swing down on the ball, and tomahawk-chop it for base hits all over the field. Then Doerr and his cronies would watch in glee as Ted erupted in profane abuse all over the child -- after which, of course, Ted would spend all day to teach that boy the full theory and practice of hitting (which included, in Ted's view, a slight uppercut).

But it wasn't just hitting, or only Red Sox. At an All-Star Game, World Series, or some other inter-tribal rite, Ted might lavish hours of attention on a hunting-dog confab with Bobby Richardson (who was, for God's sake, a Yankee). Apart from the knowledge shared, this was additionally satisfying because Ted could yell at everybody else that they might as well stay the hell away, because he and Bobby were talkin' DOGS -- about which they knew NOT A GODDAMN THING!...Or Ted might buttonhole some young man -- a player of any position, from any team -- who wasn't living up to his talent. And in the guise of a talk about hitting, Ted would teach Living Large. He'd tell them, if they would attend to the game -- instead of every gonorrheal girl who'd flop on her back, or their antique cars, or those STUPID damn drugs, or those UGLY gold chains, or ferChrist-on-a-crutch-sake PORK-BELLY FUTURES -- they could end up with a "MAJOR-LEAGUE NAME" that would be the ticket for "YER WHOLE GODDAMN LIFE!"

None of that ever saw print. For one thing, half of Ted's talk couldn't be printed in a family newspaper. For another, Ted simply wouldn't talk about it. ("WHY THE HELL SHOULD I?")...No one ever wrote, for example, that when Darryl Strawberry spiraled out of baseball in a gyre of alcohol, cocaine, and litigious women...when his imminent return to the Yankees was sadly scuttled by another acting out -- a D.U.I., or getting kicked out of rehab, or something (Straw's woes are hard to keep straight now)...the first call he got was not from his lawyer but from Ted Williams, who barely knew him, but who invited Darryl to come live at his house.

This was also pattern with Ted -- hiding the generosity of spirit that made him a great man. Maybe he assumed it would be misunderstood. Or worse still, too widely understood. "FerCHRISSAKE! YER MAKIN' ME A DAMN SOCIAL WORKER," he yelled at me one time. This was the fact he wouldn't let me print:

For years, personally and secretly, Ted had been keeping a lot of guys in business -- guys too old to qualify for baseball's pension, or they didn't have enough time in the majors, or they didn't have the talent and never made it to the majors -- and mostly they were guys too proud to ask, but he knew they were just scraping by. He'd call them up. He'd tell them he was collecting for charity -- the Jimmy Fund for kids with cancer, or his museum, something -- and they'd hem and haw about how things weren't great with them, just at the moment, might be tough to pitch in...."GODDAMMIT, I CALLED YA!" Ted would bellow into the phone. "SEND ME A CHECK FER TEN BUCKS, SONOFABITCH!"...Then, when he got their check with the number, he'd deposit ten grand into their account.

Copyright © 2002 by Richard Ben Cramer

August 30, 1918

July 5, 2002

Even in the last years of his life -- even as America and the sub-nation of baseball hungrily re-embraced him -- I knew I could provoke surprise (and more than a few arguments) when I said that Ted Williams was not just a great ballplayer, he was a great man.

Reputation dies hard in the baseball nation, and in the larger industry of American iconography. Even at the close of the century, forty years after he'd left the field, there still attached to Ted a lingering whiff of bile from the days when he spat toward booing Fenway fans. And there were heartbroken hundreds who'd freshen that scent with their stories: how he was rude to them when they tried to interrupt him for an autograph or a grip-and-grin photo. (The thousands who got their signatures or snapshots found that unremarkable.)

In the northeast corner of the nation, there were still thousands who blamed Ted for never hauling the Red Sox to World Series triumph. (Someone must bear blame for decades of disappointment when their own rooting love was so piquant and pure.)...Around New York more thousands still resented Ted -- and had to reduce him -- for contesting with Joe DiMaggio for the title of Greatest of the Golden Age. They insisted that Ted never won anything (and reviled him, in short, for never being a Yankee)....And westward through the baseball nation -- even where the game, not a team, was the passion -- historians huffed about his merit (or lack thereof) in left field; the stat-priests essayed talmudic arguments about how many runs he failed to drive in (because he'd never swing at a pitch out of the strike zone); and millions of kindly, casual fans (even those who'd agree Ted was the greatest hitter) seemed comfortable if they could tuck him into some pigeonhole -- most often as a minor freak of nature: "Wasn't it true his eyes were twice as good as a normal man's?"...

They missed the point. It wasn't his eyes, it was the avid mind behind them, and the great heart below. Ted was the greatest hitter because he knew more about that job than anyone else. He studied it relentlessly. If you knew anything about it, he wanted to know it -- and RIGHT NOW! He ripped the art into knowable shards, which he then could teach with clarity, with conviction (something he was never short on), and with surprising patience and generosity. That's how he was about anything he loved. It was the love that drove him.

Fans couldn't take their eyes off Ted because they could feel his heart yearning with theirs. His want -- in his guilelessness he never could hide it -- was ratification for theirs. If the coin of his love flipped, and all they could see was rage -- still, it was honest currency, for there was no counterfeit in him. Love and rage make a warrior...and in the inarticulate gush of words that attended his death in 2002, the particularity of our loss was lost. There were endless rehearsals of his stats, and comparisons to Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, DiMaggio (of course), Hornsby, Wagner, Mays, Aaron, Barry Bonds...there was solemn reference to his service as a pilot in two wars, and speculation on where Ted might have protruded from the great number-pile if he hadn't lost those five prime years...there were interviews that seemed intent on reassuring fans that Ted was a nice guy. But he wasn't a nice guy. He was an impossibly high-wide-and-handsome, outsized, obstreperous major-league overload of a man who dominated dugouts and made grand any ground he played on -- because his great warrior heart could fill ten ballparks. And latterly (here was our loss writ large), he was our link to that time before baseball became just another arm of the entertainment cartel.

I met Ted in 1986, in service to the entertainment biz: the editors of Esquire were scrabbling for features to fit between the ads in an issue the size of a small phone book, entitled "The American Man." And they had the inchoate sense that, somehow, Ted was The American Man. (Problem was, he was a Famously Uncooperative American Man.) So they sent me to meet him. The written product of that encounter -- you'll see it in the pages that follow -- they ran under the heading: "Mr. Everything."

But I want to spend a minute here on the unwritten product -- unwritten because it didn't come clear for years after that publication -- what I learned from that meeting with Ted. The big thing was he helped me -- when he didn't have to -- helped me to see him, understand him, feel with him, and have him in my life. He gave of himself with generosity that he knew would be unrecompensed -- and with a fearlessness about his own size that was truly exemplary -- that would change my life.

Why didn't I write that?...Well, I wrote what I understood. Anyway, I wasn't the story. But, truth be told, it was hard to tell he was helping me, when I'd leave his house all bruised from his insults and half-deaf from his latest loud evidence of how much he knew and I didn't. If I had to sum up what he showed me, it was the difference between politesse -- Ted wasn't big on that -- and what was the large, true-blue, right thing to do.

Here's one small example. In those days, I was a cigarette smoker, which horrified Ted. Not only had he never smoked, he was way ahead of his time in allowing no smoke around him. So if the urge struck, I'd idle through a Camel in his backyard, with its view of the mangroves and the Florida Bay. One day, he was shouting in his living room when the phone rang -- he started cursing. (He hated the phone, too.) I only spoke to calm him. "Go ahead, Ted, take the call. I'm goin' out back to have a smoke."

"That smokin'," he growled, "that's the WORST goddamn thing you could do. HOW OLD ARE YOU?"

"Thirty-five."

"WHEN I WAS YOUR AGE, I COULD PULL A TREE OUTA THE GROUND!...AN' LOOK AT YOU -- LOSIN' YER HAIR!"

It was later, too, I understood this was pattern with Ted. He had to rough up the people he meant to help. If you asked him about this, he would answer with a purely tactical truth -- in situations where you mean to teach, it's useful to keep clear who knows and who doesn't. But strategically this syndrome was a disaster: as a husband, father, and subject for the sporting press, it brought him unending grief. Ted's old friends couldn't explain it, but they all knew the pattern -- and richly enjoyed it. When the old-timers gathered to teach at spring training camp, Bobby Doerr, the erstwhile Sox second baseman, used to grab some young, eager Boston prospect and counsel him to go tell Ted how he meant to swing down on the ball, and tomahawk-chop it for base hits all over the field. Then Doerr and his cronies would watch in glee as Ted erupted in profane abuse all over the child -- after which, of course, Ted would spend all day to teach that boy the full theory and practice of hitting (which included, in Ted's view, a slight uppercut).

But it wasn't just hitting, or only Red Sox. At an All-Star Game, World Series, or some other inter-tribal rite, Ted might lavish hours of attention on a hunting-dog confab with Bobby Richardson (who was, for God's sake, a Yankee). Apart from the knowledge shared, this was additionally satisfying because Ted could yell at everybody else that they might as well stay the hell away, because he and Bobby were talkin' DOGS -- about which they knew NOT A GODDAMN THING!...Or Ted might buttonhole some young man -- a player of any position, from any team -- who wasn't living up to his talent. And in the guise of a talk about hitting, Ted would teach Living Large. He'd tell them, if they would attend to the game -- instead of every gonorrheal girl who'd flop on her back, or their antique cars, or those STUPID damn drugs, or those UGLY gold chains, or ferChrist-on-a-crutch-sake PORK-BELLY FUTURES -- they could end up with a "MAJOR-LEAGUE NAME" that would be the ticket for "YER WHOLE GODDAMN LIFE!"

None of that ever saw print. For one thing, half of Ted's talk couldn't be printed in a family newspaper. For another, Ted simply wouldn't talk about it. ("WHY THE HELL SHOULD I?")...No one ever wrote, for example, that when Darryl Strawberry spiraled out of baseball in a gyre of alcohol, cocaine, and litigious women...when his imminent return to the Yankees was sadly scuttled by another acting out -- a D.U.I., or getting kicked out of rehab, or something (Straw's woes are hard to keep straight now)...the first call he got was not from his lawyer but from Ted Williams, who barely knew him, but who invited Darryl to come live at his house.

This was also pattern with Ted -- hiding the generosity of spirit that made him a great man. Maybe he assumed it would be misunderstood. Or worse still, too widely understood. "FerCHRISSAKE! YER MAKIN' ME A DAMN SOCIAL WORKER," he yelled at me one time. This was the fact he wouldn't let me print:

For years, personally and secretly, Ted had been keeping a lot of guys in business -- guys too old to qualify for baseball's pension, or they didn't have enough time in the majors, or they didn't have the talent and never made it to the majors -- and mostly they were guys too proud to ask, but he knew they were just scraping by. He'd call them up. He'd tell them he was collecting for charity -- the Jimmy Fund for kids with cancer, or his museum, something -- and they'd hem and haw about how things weren't great with them, just at the moment, might be tough to pitch in...."GODDAMMIT, I CALLED YA!" Ted would bellow into the phone. "SEND ME A CHECK FER TEN BUCKS, SONOFABITCH!"...Then, when he got their check with the number, he'd deposit ten grand into their account.

Copyright © 2002 by Richard Ben Cramer

Notă biografică

Richard Ben Cramer