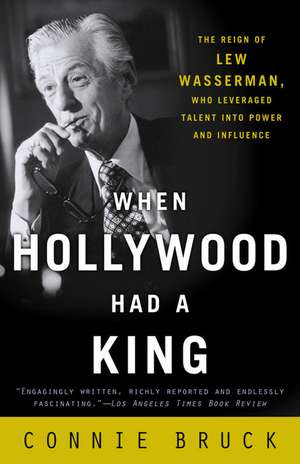

When Hollywood Had a King: The Reign of Lew Wasserman, Who Leveraged Talent Into Power and Influence

Autor Connie Brucken Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2004

The Music Corporation of America was founded in Chicago in 1924 by Dr. Jules Stein, an ophthalmologist with a gift for booking bands. Twelve years later, Stein moved his operations west to Beverly Hills and hired Lew Wasserman. From his meager beginnings as a movie-theater usher in Cleveland, Wasserman ultimately ascended to the post of president of MCA, and the company became the most powerful force in Hollywood, regarded with a mixture of fear and awe.

In his signature black suit and black knit tie, Was-serman took Hollywood by storm. He shifted the balance of power from the studios—which had seven-year contractual strangleholds on the stars—to the talent, who became profit partners. When an antitrust suit forced MCA’s evolution from talent agency to film- and television-production company, it was Wasserman who parlayed the control of a wide variety of entertainment and media products into a new type of Hollywood power base. There was only Washington left to conquer, and conquer it Wasserman did, quietly brokering alliances with Democratic and Republican administrations alike.

That Wasserman’s reach extended from the underworld to the White House only added to his mystique. Among his friends were Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa, mob lawyer Sidney Korshak, and gangster Moe Dalitz—along with Presidents Johnson, Clinton, and especially Reagan, who enjoyed a particularly close and mutually beneficial relationship with Wasserman. He was equally intimate with Hollywood royalty, from Bette Davis and Jimmy Stewart to Steven Spielberg, who began his career at MCA and once described Wasserman’s eyeglasses as looking like two giant movie screens.

The history of MCA is really the history of a revolution. Lew Wasserman ushered in the Hollywood we know today. He is the link between the old-school moguls with their ironclad studio contracts and the new industry defined by multimedia conglomerates, power agents, multimillionaire actors, and profit sharing. In the hands of Connie Bruck, the story of Lew Wasserman’s rise to power takes on an almost Shakespearean scope. When Hollywood Had a King reveals the industry’s greatest untold story: how a stealthy, enterprising power broker became, for a time, Tinseltown’s absolute monarch.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 128.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.62€ • 25.55$ • 20.58£

24.62€ • 25.55$ • 20.58£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 februarie-10 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812972177

ISBN-10: 0812972171

Pagini: 528

Ilustrații: 21 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812972171

Pagini: 528

Ilustrații: 21 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Connie Bruck has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1989; she frequently writes about business and politics. In 1996, her profile of Newt Gingrich won the National Magazine Award for reporting, her second. Bruck is the author of Master of the Game and The Predators’ Ball. She lives in Los Angeles.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

The two caesars

On a spring day in Chicago in 1922, two young men stood deep in conversation on the sidewalk outside the headquarters of Local 10, a branch of the American Federation of Musicians union. They might have conferred inside the building instead-one of them, James Caesar Petrillo, was the local's vice president-but he thought the walls had ears, and the message he wanted to deliver was confidential. He had sent word to his companion, Jules Caesar Stein, that he wanted to see him. Stein was a recent medical school graduate who booked bands on the side, and, in his relatively short career, he had already run afoul of the musicians union, and gotten caught in the crossfire of Chicago's ongoing, internecine labor wars. It seemed, moreover, to be Petrillo's fire that had caught Stein; the bombs that had recently exploded at several Chinese restaurants where Stein was booking bands were Petrillo's handiwork, Stein was convinced. At one of them, the Canton Tea Garden on Wabash, the damage had been especially severe. But the nature of the band-booking business-and more, of the city itself-was such that Stein had little recourse. If he wanted to continue in this business, he had to make his peace with this, the dominant musicians union. So he was eager to hear what Petrillo had to say.

Stein had entered this business at a young age-he was only seventeen when he began assembling and booking bands as a means of putting himself through school-but he had grasped the power of the union from the start. In the first few years, he had booked bands mainly in summer resort areas, always employing members of the Federation (AFM). But one summer, unable to fill an orchestra for a resort engagement at Lake Okoboji in Iowa, he had engaged a nonunion musician, hoping his transgression would remain secret. The information, predictably, leaked out; he was brought before the board of Local 10, then headed by its president, Joseph Winkler, fined $1,500 (a sum he could not hope to pay), and expelled from the union. So Stein had joined a rival union, an independent group called the American Musicians Union (AMU), which was far less powerful than the AFM. And he began to book Chinese restaurants with AMU musicians. To Petrillo, this was tantamount to a declaration of war; he considered the Chinese restaurants his personal fiefdom. When he had joined Local 10 in 1919, he had been assigned the task of organizing the musicians in these restaurants. Other union members had been trying to do this, off and on, for nearly two decades; Petrillo had it wrapped up in about one month. According to one story, perhaps apocryphal, Petrillo had walked into one of these restaurants, placed a time bomb on the table, and demanded that the owner sign a contract before the device exploded.

Now, the very capable Petrillo was offering Stein a truce. He said he would cancel Stein's expulsion and allow him to pay a reduced fine, $500, over a period of months, to rejoin the AFM. If Stein felt any anger at Petrillo for his violent acts, he was too pragmatic to let it show. He promptly agreed to Petrillo's proposition, and thanked him. How Petrillo had the authority to lift Stein's punishment-inasmuch as Winkler, who had levied it, was still the president-is not clear. But not long after this exchange, a series of dramatic events took place at Local 10. Winkler, while presiding over a board meeting, was attacked by the union's business agent, who hit him over the head repeatedly, apparently with metal knuckles, fracturing his skull, while all the assembled directors watched; and about six weeks later, as Winkler was slowly recovering, a bomb exploded in Local 10's offices. Shortly after the bombing, a union member wrote a letter to the editor of the International Musician, in which he declared that the violence was due to a faction within the union opposed to Winkler, which "seemingly had but one desire, namely, to advance their own selfish individual interests"-and he implied that this faction included Petrillo. Stein, moreover, would recall years later that, after he and Petrillo had had their rapprochement, Petrillo "ousted" Winkler. In December 1922, Petrillo was duly elected president of the local.

The alliance that had been forged between Stein and Petrillo on the sidewalk that day would last the rest of their lives. To a casual observer, they were the strangest of consorts. Stein, who was very conscious of his professional status, cultivated a rather formal, even courtly mien, and a gentleman's image-dressing in dark, double-breasted suits, parting his hair in the middle, sporting a pince-nez; and he was singularly self-contained, betraying little emotion, choosing his words as warily as though he had to pay for them. Petrillo, on the other hand, a rough type who looked very much the saloon-keeper he'd been until he decided to make his way in what he called "the union business," had devoted nine years to school but never could get beyond the fourth grade-something suggested in his signature, which always remained an exemplar of beginning penmanship, and, most noticeably, in his speech. He was a stubby volcano of a man, erupting at the slightest provocation in streams of tortured syntax peppered with profanity, and delivered, raspingly, out of the corner of his mouth. But the two men did share other characteristics, less immediately evident: shrewdness in their judgments about people, organizational skills, and (as suggested by their middle names) a taste for empire building. Though they were both instinctively suspicious, distrusting virtually everyone, they knew at least some of each other's secrets. And, in these critical, early years, each would do more to pave the way for the other's steep ascent than any other individual. Much later, when Stein was a world-famous businessman and philanthropist, he would attempt to distance himself from some of his early Chicago connections, and he would substantially revise that history. But he would never turn his back on Petrillo.

Petrillo was given the name Caesar at birth, but Stein took it for himself when he was a teenager. Later, he would regret this adolescent gesture as too flamboyant and, worse, revealing. But at the time, it was his declaration that he was impatient to put the torpor of life in South Bend, Indiana, behind him, and to conquer the world. He was born on April 26, 1896, to Rosa and Louis Stein. Louis (whose family name was changed from Seimenski) had emigrated from Lithuania; initially he made his way as a peddler, carrying a heavy pack of goods on his back, and ultimately he opened a dry goods store in South Bend; and Jules's mother, Rosa Cohen, also from Lithuania, was sent here by her parents to be Louis's bride. Orthodox Jews, Rosa and Louis had five children; Jules was the second son. The family lived in a run-down neighborhood with vestiges of past elegance; their two-story house adjoined Louis's general store, where all the children worked. The value of money was inculcated in them early. Stein would learn much later that one of his grandfathers had been a rabbi, and a great-grandfather a scholar of some renown (and so devout that when he was told, during a Sabbath service, that his daughter had just died, he displayed no emotion and simply continued with his prayers); but this came as a surprise to Jules, who had believed that he was the first of his family to be well educated. In his parents' household, it was not scholarship but business acumen that was prized; Jews from Lithuania, who were called Litvaks, were known for their financial prowess. As Shalom

Aleichem, whose sayings reflected the sentiments of many Middle European Jews, wrote: "If you have money, you are not only clever, but handsome too, and can sing like a nightingale."

The store where Jules spent much of his childhood was a narrow, cluttered space-twenty-five by one hundred feet-overflowing with merchandise. In the long showcases, and on the shelves that lined the walls from the floor to the ceiling (a ladder on wheels ran on a railing along the shelves, so even the children could reach the high items) were piles of men's and women's clothing, shoes, dress patterns, cloth, balls of wool. In a cage in the center stood the cash register. The customers were workers and farmers; barter was common, negotiation constant. Always vigilant for theft, the family developed secret codes in order to communicate. Spotting a possible shoplifter, one family member would call out the name of another, closest to the suspect, and shout, "21!" They also devised what they called the GOLDBERKS code, in which G stood for 1, O for 2, and so forth; P or X stood for 0. (Many years later, when Jules would make his younger sister, Ruth, his financial assistant-the only person he trusted in this capacity-he would use this code to send her messages from abroad.) They used the code to mark merchandise so that, when the inevitable negotiations ensued, they would know what they had paid for it but the customers would not. It was almost scriptural that one must never be taken advantage of, but, rather, must get the better end of the deal. And it followed, too, that money so hard-earned was to be spent frugally; thus, since the bus to school cost a nickel, Jules and his siblings often chose to walk rather than spend the five cents.

It was not lost upon Jules that, hardworking as his father was, the family remained poor; if business acumen was the measure of a man, his father fell short. Perhaps Louis Stein knew his son viewed him critically. Louis was adept with his hands, and had wrought an iron fence that stood in front of their house; he liked to make constructions out of pipes, which Rosa viewed as a vulgar hobby. Jules, who also enjoyed crafts and gadgetry, sent away for a kit for making an English antique-style desk; when he brought it home from carpentry class, his father ridiculed it, declaring it should be thrown out, but his mother placed it in the center of the living room, where it remained for many years. Jules, in any event, felt an affinity for his mother-a warm, open-faced woman with a clear gaze-but not his father. He was a child who never seemed childlike; he never learned to swim because his mother warned him the water was dangerous, he trudged to school in the company of his thoughts, alone, and from an early age he seemed to feel responsible for his siblings. "Jules was like a father," his sister Ruth said, recalling how her older brother would reward her with money for excellent report cards. He was intent on making money; when he was about eleven, he began playing the violin, and within a couple years he had found a way to make that pastime pay. He formed an orchestra with four or five other youngsters, and they performed for small parties-their favorite number was "Alexander's Ragtime Band." Jules also accompanied a pianist in a nickelodeon movie theater, for which he received seven passes per week. Soon, he added the saxophone to his repertoire to increase his marketability.

Because Jules was in a great hurry to escape the confines of South Bend, he enrolled in summer school at Winona Lake Academy to accelerate his high school schedule. It was his first time away from home, and he was so homesick he almost quit; but then he decided to promote Saturday night dances for the students of his school and also the University of Indiana summer school, and he became so engrossed in this activity he forgot his homesickness. He found a dance hall in Warsaw, a few miles away; arranged for a streetcar line to run a special car from Warsaw back to Winona at midnight; printed postcards announcing these dances and sent them to all the students. "This was my first dance promotion," he recalled in a series of interviews conducted by former New York Times reporter Murray Schumach in the 1970s. Upon graduating from high school at sixteen, Stein commenced what he later referred to as "negotiations" with colleges-proposing that he would play in the school band in exchange for free tuition. The best offer came from the University of West Virginia-not only free tuition and books but a job playing in the local Swisher Theatre two nights a week, for about $5 a night. During the two years he spent there, Stein came up with another business venture; realizing that students had trouble locating one another, he solicited ads from merchants and put out a student guide-in which his name appeared in letters larger than all the rest. ("That was a mistake," he said later. "I never did anything like that again." Stein seemed to consider it vulgar. Indeed, cultivating personal anonymity would become one of the hallmarks of his business life.) The following summer, he formed his own band and played in hotels; he also gave dance lessons in the fox-trot, two-step, and waltz. After graduating at eighteen from the University of West Virginia, Stein attended the University of Chicago for a year of postgraduate study; he continued to receive tuition free in exchange for playing in the band, and he found Chicago a far more lucrative market for booking other band dates. Soon, Stein realized he could make more money booking bands than playing in them; and, when he booked them for a summer stint at a resort, he found other opportunities as well. At Charlevoix, Michigan, in the summer of 1919, he not only provided musicians for the season but also paid to lease the hotel beauty parlor and barbershop and haberdashery, which he then ran-an instinct for dominating numerous venues that would become more pronounced over time.Thanks to his band booking, Stein was able to put himself through medical school in Chicago (it was said that during his internship at Cook County Hospital he set the record for the greatest number of tonsillectomies performed in one day), and was even able to spend a year in eye research at the University of Vienna. Traveling through Germany during a period of extreme inflation, he kept a detailed diary of his expenditures, which were minimized by the relative strength of the dollar (for example, he spent 65 cents for an overnight train from Leipzig to Berlin). While Stein took great satisfaction in recording his economies, he also developed a lasting fear that inflation might someday wipe out all his savings. By 1924, he had completed his studies, and he was working for well-regarded Chicago ophthalmologist Dr. Harry Gredel. But medicine was not what compelled him; money was. So that year, with $3,000 in capital, Stein started a band-booking agency he called the Music Corporation of America.

From the Hardcover edition.

The two caesars

On a spring day in Chicago in 1922, two young men stood deep in conversation on the sidewalk outside the headquarters of Local 10, a branch of the American Federation of Musicians union. They might have conferred inside the building instead-one of them, James Caesar Petrillo, was the local's vice president-but he thought the walls had ears, and the message he wanted to deliver was confidential. He had sent word to his companion, Jules Caesar Stein, that he wanted to see him. Stein was a recent medical school graduate who booked bands on the side, and, in his relatively short career, he had already run afoul of the musicians union, and gotten caught in the crossfire of Chicago's ongoing, internecine labor wars. It seemed, moreover, to be Petrillo's fire that had caught Stein; the bombs that had recently exploded at several Chinese restaurants where Stein was booking bands were Petrillo's handiwork, Stein was convinced. At one of them, the Canton Tea Garden on Wabash, the damage had been especially severe. But the nature of the band-booking business-and more, of the city itself-was such that Stein had little recourse. If he wanted to continue in this business, he had to make his peace with this, the dominant musicians union. So he was eager to hear what Petrillo had to say.

Stein had entered this business at a young age-he was only seventeen when he began assembling and booking bands as a means of putting himself through school-but he had grasped the power of the union from the start. In the first few years, he had booked bands mainly in summer resort areas, always employing members of the Federation (AFM). But one summer, unable to fill an orchestra for a resort engagement at Lake Okoboji in Iowa, he had engaged a nonunion musician, hoping his transgression would remain secret. The information, predictably, leaked out; he was brought before the board of Local 10, then headed by its president, Joseph Winkler, fined $1,500 (a sum he could not hope to pay), and expelled from the union. So Stein had joined a rival union, an independent group called the American Musicians Union (AMU), which was far less powerful than the AFM. And he began to book Chinese restaurants with AMU musicians. To Petrillo, this was tantamount to a declaration of war; he considered the Chinese restaurants his personal fiefdom. When he had joined Local 10 in 1919, he had been assigned the task of organizing the musicians in these restaurants. Other union members had been trying to do this, off and on, for nearly two decades; Petrillo had it wrapped up in about one month. According to one story, perhaps apocryphal, Petrillo had walked into one of these restaurants, placed a time bomb on the table, and demanded that the owner sign a contract before the device exploded.

Now, the very capable Petrillo was offering Stein a truce. He said he would cancel Stein's expulsion and allow him to pay a reduced fine, $500, over a period of months, to rejoin the AFM. If Stein felt any anger at Petrillo for his violent acts, he was too pragmatic to let it show. He promptly agreed to Petrillo's proposition, and thanked him. How Petrillo had the authority to lift Stein's punishment-inasmuch as Winkler, who had levied it, was still the president-is not clear. But not long after this exchange, a series of dramatic events took place at Local 10. Winkler, while presiding over a board meeting, was attacked by the union's business agent, who hit him over the head repeatedly, apparently with metal knuckles, fracturing his skull, while all the assembled directors watched; and about six weeks later, as Winkler was slowly recovering, a bomb exploded in Local 10's offices. Shortly after the bombing, a union member wrote a letter to the editor of the International Musician, in which he declared that the violence was due to a faction within the union opposed to Winkler, which "seemingly had but one desire, namely, to advance their own selfish individual interests"-and he implied that this faction included Petrillo. Stein, moreover, would recall years later that, after he and Petrillo had had their rapprochement, Petrillo "ousted" Winkler. In December 1922, Petrillo was duly elected president of the local.

The alliance that had been forged between Stein and Petrillo on the sidewalk that day would last the rest of their lives. To a casual observer, they were the strangest of consorts. Stein, who was very conscious of his professional status, cultivated a rather formal, even courtly mien, and a gentleman's image-dressing in dark, double-breasted suits, parting his hair in the middle, sporting a pince-nez; and he was singularly self-contained, betraying little emotion, choosing his words as warily as though he had to pay for them. Petrillo, on the other hand, a rough type who looked very much the saloon-keeper he'd been until he decided to make his way in what he called "the union business," had devoted nine years to school but never could get beyond the fourth grade-something suggested in his signature, which always remained an exemplar of beginning penmanship, and, most noticeably, in his speech. He was a stubby volcano of a man, erupting at the slightest provocation in streams of tortured syntax peppered with profanity, and delivered, raspingly, out of the corner of his mouth. But the two men did share other characteristics, less immediately evident: shrewdness in their judgments about people, organizational skills, and (as suggested by their middle names) a taste for empire building. Though they were both instinctively suspicious, distrusting virtually everyone, they knew at least some of each other's secrets. And, in these critical, early years, each would do more to pave the way for the other's steep ascent than any other individual. Much later, when Stein was a world-famous businessman and philanthropist, he would attempt to distance himself from some of his early Chicago connections, and he would substantially revise that history. But he would never turn his back on Petrillo.

Petrillo was given the name Caesar at birth, but Stein took it for himself when he was a teenager. Later, he would regret this adolescent gesture as too flamboyant and, worse, revealing. But at the time, it was his declaration that he was impatient to put the torpor of life in South Bend, Indiana, behind him, and to conquer the world. He was born on April 26, 1896, to Rosa and Louis Stein. Louis (whose family name was changed from Seimenski) had emigrated from Lithuania; initially he made his way as a peddler, carrying a heavy pack of goods on his back, and ultimately he opened a dry goods store in South Bend; and Jules's mother, Rosa Cohen, also from Lithuania, was sent here by her parents to be Louis's bride. Orthodox Jews, Rosa and Louis had five children; Jules was the second son. The family lived in a run-down neighborhood with vestiges of past elegance; their two-story house adjoined Louis's general store, where all the children worked. The value of money was inculcated in them early. Stein would learn much later that one of his grandfathers had been a rabbi, and a great-grandfather a scholar of some renown (and so devout that when he was told, during a Sabbath service, that his daughter had just died, he displayed no emotion and simply continued with his prayers); but this came as a surprise to Jules, who had believed that he was the first of his family to be well educated. In his parents' household, it was not scholarship but business acumen that was prized; Jews from Lithuania, who were called Litvaks, were known for their financial prowess. As Shalom

Aleichem, whose sayings reflected the sentiments of many Middle European Jews, wrote: "If you have money, you are not only clever, but handsome too, and can sing like a nightingale."

The store where Jules spent much of his childhood was a narrow, cluttered space-twenty-five by one hundred feet-overflowing with merchandise. In the long showcases, and on the shelves that lined the walls from the floor to the ceiling (a ladder on wheels ran on a railing along the shelves, so even the children could reach the high items) were piles of men's and women's clothing, shoes, dress patterns, cloth, balls of wool. In a cage in the center stood the cash register. The customers were workers and farmers; barter was common, negotiation constant. Always vigilant for theft, the family developed secret codes in order to communicate. Spotting a possible shoplifter, one family member would call out the name of another, closest to the suspect, and shout, "21!" They also devised what they called the GOLDBERKS code, in which G stood for 1, O for 2, and so forth; P or X stood for 0. (Many years later, when Jules would make his younger sister, Ruth, his financial assistant-the only person he trusted in this capacity-he would use this code to send her messages from abroad.) They used the code to mark merchandise so that, when the inevitable negotiations ensued, they would know what they had paid for it but the customers would not. It was almost scriptural that one must never be taken advantage of, but, rather, must get the better end of the deal. And it followed, too, that money so hard-earned was to be spent frugally; thus, since the bus to school cost a nickel, Jules and his siblings often chose to walk rather than spend the five cents.

It was not lost upon Jules that, hardworking as his father was, the family remained poor; if business acumen was the measure of a man, his father fell short. Perhaps Louis Stein knew his son viewed him critically. Louis was adept with his hands, and had wrought an iron fence that stood in front of their house; he liked to make constructions out of pipes, which Rosa viewed as a vulgar hobby. Jules, who also enjoyed crafts and gadgetry, sent away for a kit for making an English antique-style desk; when he brought it home from carpentry class, his father ridiculed it, declaring it should be thrown out, but his mother placed it in the center of the living room, where it remained for many years. Jules, in any event, felt an affinity for his mother-a warm, open-faced woman with a clear gaze-but not his father. He was a child who never seemed childlike; he never learned to swim because his mother warned him the water was dangerous, he trudged to school in the company of his thoughts, alone, and from an early age he seemed to feel responsible for his siblings. "Jules was like a father," his sister Ruth said, recalling how her older brother would reward her with money for excellent report cards. He was intent on making money; when he was about eleven, he began playing the violin, and within a couple years he had found a way to make that pastime pay. He formed an orchestra with four or five other youngsters, and they performed for small parties-their favorite number was "Alexander's Ragtime Band." Jules also accompanied a pianist in a nickelodeon movie theater, for which he received seven passes per week. Soon, he added the saxophone to his repertoire to increase his marketability.

Because Jules was in a great hurry to escape the confines of South Bend, he enrolled in summer school at Winona Lake Academy to accelerate his high school schedule. It was his first time away from home, and he was so homesick he almost quit; but then he decided to promote Saturday night dances for the students of his school and also the University of Indiana summer school, and he became so engrossed in this activity he forgot his homesickness. He found a dance hall in Warsaw, a few miles away; arranged for a streetcar line to run a special car from Warsaw back to Winona at midnight; printed postcards announcing these dances and sent them to all the students. "This was my first dance promotion," he recalled in a series of interviews conducted by former New York Times reporter Murray Schumach in the 1970s. Upon graduating from high school at sixteen, Stein commenced what he later referred to as "negotiations" with colleges-proposing that he would play in the school band in exchange for free tuition. The best offer came from the University of West Virginia-not only free tuition and books but a job playing in the local Swisher Theatre two nights a week, for about $5 a night. During the two years he spent there, Stein came up with another business venture; realizing that students had trouble locating one another, he solicited ads from merchants and put out a student guide-in which his name appeared in letters larger than all the rest. ("That was a mistake," he said later. "I never did anything like that again." Stein seemed to consider it vulgar. Indeed, cultivating personal anonymity would become one of the hallmarks of his business life.) The following summer, he formed his own band and played in hotels; he also gave dance lessons in the fox-trot, two-step, and waltz. After graduating at eighteen from the University of West Virginia, Stein attended the University of Chicago for a year of postgraduate study; he continued to receive tuition free in exchange for playing in the band, and he found Chicago a far more lucrative market for booking other band dates. Soon, Stein realized he could make more money booking bands than playing in them; and, when he booked them for a summer stint at a resort, he found other opportunities as well. At Charlevoix, Michigan, in the summer of 1919, he not only provided musicians for the season but also paid to lease the hotel beauty parlor and barbershop and haberdashery, which he then ran-an instinct for dominating numerous venues that would become more pronounced over time.Thanks to his band booking, Stein was able to put himself through medical school in Chicago (it was said that during his internship at Cook County Hospital he set the record for the greatest number of tonsillectomies performed in one day), and was even able to spend a year in eye research at the University of Vienna. Traveling through Germany during a period of extreme inflation, he kept a detailed diary of his expenditures, which were minimized by the relative strength of the dollar (for example, he spent 65 cents for an overnight train from Leipzig to Berlin). While Stein took great satisfaction in recording his economies, he also developed a lasting fear that inflation might someday wipe out all his savings. By 1924, he had completed his studies, and he was working for well-regarded Chicago ophthalmologist Dr. Harry Gredel. But medicine was not what compelled him; money was. So that year, with $3,000 in capital, Stein started a band-booking agency he called the Music Corporation of America.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

From When Hollywood Had a King

On Lew Wasserman:

“He helped me become president, he helped me stay president, he helped me be a better president.” —Bill Clinton

“If Hollywood was Mount Olympus, Lew Wasserman is Zeus.” —Jack Valenti

“At a time when the general image of business executives is not sterling, Lew Wasserman is the gold standard.” —Barry Diller

“I’m a very simple man.” —Lew Wasserman, to President Lyndon Baines Johnson

From the Hardcover edition.

On Lew Wasserman:

“He helped me become president, he helped me stay president, he helped me be a better president.” —Bill Clinton

“If Hollywood was Mount Olympus, Lew Wasserman is Zeus.” —Jack Valenti

“At a time when the general image of business executives is not sterling, Lew Wasserman is the gold standard.” —Barry Diller

“I’m a very simple man.” —Lew Wasserman, to President Lyndon Baines Johnson

From the Hardcover edition.