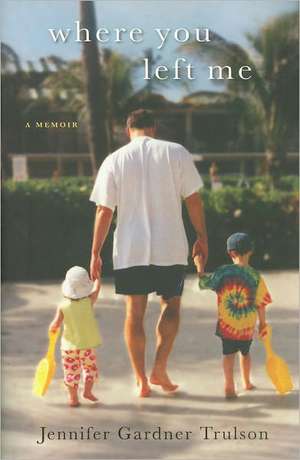

Where You Left Me

Autor Jennifer Gardner Trulsonen Limba Engleză Hardback – 29 aug 2011

Lucky—that’s how Jennifer would describe herself. She had a successful law career, met the love of her life in Doug, married him, had an apartment in New York City, a house in the Hamptons, two beautiful children, and was still madly in love after nearly seven years of marriage. Jennifer was living the kind of idyllic life that clichés are made of.

Until Doug was killed in the attacks on the World Trade Center, and she became a widow at age thirty-five—a “9/11 widow,” no less, a member of a select group bound by sorrow, of which she wanted no part. Though completely devastated, Jennifer still considered herself blessed. Doug had loved her enough to last her a lifetime, and after his sudden death, she was done with the idea of romantic love—fully resigned to being a widowed single mother . . . until a chance encounter with a gregarious stranger changed everything. Without a clue how to handle this unexpected turn of events, Jennifer faced the question asked by anyone who has ever lost a loved one: Is it really possible to feel joy again, let alone love?

With unvarnished emotion and clear-eyed sardonic humor, Jennifer tells an ordinary woman’s extraordinary tale of unimaginable loss, resilience, friendship, love, and healing—which is also New York City’s narrative in the wake of September 11. Where You Left Me is an unlikely love story, a quintessentially New York story—at once Jennifer’s tribute to the city that gave her everything and proof that second chances are possible.

Preț: 180.14 lei

Nou

34.47€ • 36.86$ • 28.74£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Specificații

ISBN-10: 1451621426

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 156 x 235 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Extras

“It’s coming down,” I said to myself as I blearily looked out my office window on the thirtieth floor at 1585 Broadway. The snowstorm had picked up, and Times Square slept under a deep cover of untouched snow. It was a rare sight, even at 1:00 a.m.—not a car or pedestrian to be seen for blocks under the blazing neon lights and billboards. I was used to working late, churning out contracts, memos, and research day and night as a third-year associate at a law firm. And normally, I’d take a town car home at this hour, but not even taxis were out in this weather—nothing had been plowed and the sidewalks were piled high with four-foot drifts of snow. How the hell was I going to get home? Walking wasn’t an option, I lived all the way across town on First Avenue. The subway was running, but I wasn’t about to take a train home alone from Times Square at one in the morning.

I went back up to my office and nervously called Doug. Doug and I had been seeing each other steadily since our first date at Café Luxembourg four months earlier. It was a blind date, my third one that week. My job didn’t afford me much time for a proper social life, leaving me at the mercy of my friends to make introductions. At first, I wasn’t sure Doug could be the one for me. Yes, he was handsome—six foot four with clear blue eyes, a radiant smile, and the large build of a professional quarterback. It took me two dates to realize that he had a small bald spot on the top of his head because he towered over me by nearly a foot. He was also fiercely intelligent and attentive, but I worried that he might be a little too reserved and formal. Doug was born and raised in Manhattan, a true city boy who relished the pace of his hometown and seemed to know everyone. I grew up in Longmeadow, a small town in Massachusetts, and had only moved to the city two years prior after graduating from Harvard Law School. I hardly knew anyone, but I loved New York—the frenetic energy, crowded sidewalks, and diverse neighborhoods sang to me.

I was further thrown by my realization that Doug was also a grown-up, a creature I had never dated before. He was five years older than I, took me to popular restaurants and cultural events around the city, and he always paid, dropped me off at my door, and called the next day. This gallant behavior confused me. I was used to meeting dates at neighborhood dives and splitting the check.

For weeks, he courted me in his old-fashioned manner, and I vacillated between being attracted to him and questioning whether I really wanted to continue the relationship. I was twenty-seven years old, what did I know? Doug, however, had what I liked to call a healthy self-image and watched me with great amusement while I turned myself into a pretzel trying to figure out where we stood. One night in October, while standing in line to see The Age of Innocence, I casually remarked that, maybe, I liked him only “as a friend,” and that we should leave it at that. He lifted my chin with his hand and said confidently, “I’m not worried about you. You’ll smarten up.”

.....

Doug answered the phone in his loft on West Fifteenth Street with a sleepy “Hello?” I apologized for waking him and asked if he could convince one of his company’s car services to send a car to take me home. Doug was a senior executive at Cantor Fitzgerald, an international brokerage firm run by his best friend from college, Howard Lutnick. Apart from a few years at Lehman Brothers right after graduating from Haverford College, Doug had spent the better part of the last decade working with his father in the family real estate development and management business. But as the housing market softened in the early nineties, he was ready for a new challenge when Howard offered him the position and Doug gladly accepted.

When I called that night, Doug told me to wait in the lobby—he was coming to get me himself—then hung up before I could stop him. Twenty minutes later, as I stood in the empty lobby in my impractical heels, watching the wind whip clouds of snow around the dark, deserted streets, I saw his large frame lumbering through the snowy drifts to my building. Poorly dressed for the weather, Doug’s wide-open parka flapped in the wind, and one leg of his sweatpants was tucked into his Timberlands while the other hung loose at his ankle. When he arrived at the door, Doug’s bare head and shoulders were covered in snowflakes, and his round glasses were dripping wet. “Come with me,” my disheveled knight said with a breathless smile. He reached out his hand and carried me through the snow, into the subway and home to safety.

September 10, 2001

Doug’s fortieth birthday was coming up and I decided to surprise him with a Studio 54–themed party—vintage costumes, psychedelic décor, and all the Bee Gees music one could stand. Doug had an unnatural attachment to this era—he often ordered double- disc sets of seventies hits from late-night infomercials. The party was scheduled for the first Saturday of October, and I mailed the invitations that afternoon; the front of the colorful card said “Burn, Baby, Burn.”

That evening, Doug met me on West Sixty-Eighth Street at our children’s preschool, Stephen Wise Synagogue, for parent orientation. The next day, Tuesday the eleventh, Michael, our four-year-old, would have his first day of prekindergarten. Julia, our two-and-a-half-year-old, would start preschool for the first time on Wednesday. I was already sitting in a child-size wooden chair in Michael’s classroom with the other parents in a semicircle when Doug’s face appeared in the doorway. His bright blue eyes found mine, and he carefully navigated through the crowded classroom to join me. It didn’t matter how long we’d been together, my heart literally jumped whenever he entered a room. All of the chairs were taken; I slid to the floor so that my tall husband could sit. “Hi, Bunny,” he whispered in my ear as I settled against his legs. While the teacher spoke, Doug unconsciously stroked my hair as he always did and valiantly tried to sit patiently, folded up like a grizzly bear in a baby’s car seat. We took turns visiting each child’s classroom and placed good luck notes in Michael’s and Julia’s cubbies.

When orientation ended, Doug’s glance told me that he wanted to get right home to the kids before their bedtimes; no parent-to-parent small talk. Doug and I had nearly perfected the art of private marital communication in public places. A raised eyebrow, a tickle on the back of my arm, or a well-timed kiss on the cheek would signal, “Wrap it up, I want you to myself.” On the rare occasion I missed one of his signs or continued to embed myself in conversation, he’d raise the stakes and call me Abby, as in, “Abby, you look lovely tonight.” Abby stood for “oblivious,” and it was Doug’s covert way of telling me to stop talking. I stopped. Immediately. What wife wouldn’t happily oblige a husband who couldn’t wait to steal any moment he could to be alone with her?

On the morning of September 11, the alarm buzzed at 5:30 a.m., and Doug lurched out of bed to meet his trainer at our gym. I went back to sleep and woke an hour later to his big, scratchy face rubbing against my cheek. “Wake up, beautiful.” He always woke me this way, unless Michael had already scampered under the covers for a morning snuggle. After Doug showered, I followed him to our small office down the hall where he kept his work clothes. I sat at the desk in my bathrobe while he got dressed—loafers, khaki trousers, a brown leather belt. He was particularly delighted to show me the new blue oxford shirt he’d bought the day before at Rothmans in Union Square. “See, I picked it out myself,” he proudly said as he turned from side to side, playfully modeling for me. “I’m very impressed, Grasshopper,” I replied, taking note of this historic moment. Doug hated shopping and could wear his clothes until they were threadbare and tragically out of style. Ever since we’d gotten married, he’d gratefully assigned me the task of dressing him and rarely bought anything on his own.

Today was going to be special. It was Michael’s first day of school and Doug’s father’s seventy-second birthday; we planned to take the kids for the first time to dinner at a “grown-up” restaurant, Shun Lee, to celebrate with the grandparents. Doug couldn’t take Michael to school since he had scheduled early meetings at the office that he wanted to handle in order to keep our five-o’clock dinner reservation. Ironically, Doug was supposed to have been traveling that day, but postponed the trip to celebrate his dad’s birthday and mark Julia’s first day of preschool on the twelfth.

I actually ribbed Doug a little for not accompanying us to school that morning. “You’ll miss Michael’s first-day pictures. He’ll remember this.” Doug gave me his usual bemused I’m-the-best-thing-that-ever-happened-to-you look and told me not to kvetch. Honestly, I wasn’t upset at all. Doug never really irritated me. Occasionally we’d bicker or roll our eyes at each other, but no argument ever escalated into a bitter exchange. Doug was my hero. It sounds pat—as if I’m sanctifying him—but it’s the truth. He specifically promised me three things before we got married: he promised he would always “be big,” make me “feel good,” and “take care of things.” In exchange, I adored him and solemnly swore that I would never, ever, make him live outside of Manhattan. I think I have that promise in writing somewhere.

Doug regularly fulfilled his three promises (and relished reminding me which one he was accomplishing). He was “big” when he carried the heavy luggage at the airport and “took care of things” when he interrupted a business meeting to call a plumber about an overflowing washing machine because I was too flummoxed by the rising water. For all of this, I did my best to make our home a safe, calm space with minimal demands. I’d left my job as legal counsel at the New York Times after Julia was born and worried that my brain would atrophy as a stay-at-home mom. To my surprise, I found that being a wife and mother fulltime was the most fulfilling job I’d ever had. Doug made me feel that what I was doing mattered, and nothing made me happier than creating a safe haven in which we could nest. I made sure that, after work, he could move effortlessly from the kids to dinner to a late basketball league game to falling asleep to Law & Order. I attended Knicks games at Madison Square Garden (Doug, a rabid fan, shared season tickets with a college buddy) and dutifully rewatched them on videotape when we got home, so Doug could share his analysis of important plays with an attentive listener. I learned to respect Doug’s sometimes exasperating passion for the Knicks—I will never forget making the mistake of attempting to read the New York Post at the Garden during a particularly uneventful game against the Mavericks (a weak team at the time). Doug tore the paper out of my hands and threw it to the ground. “What?” I asked incredulously. “Why do you care? You never talk to me during games.” He answered with a semi-serious growl, “In the event I want to discuss a play or point out a mismatch, you must know what I’m talking about.” After that moment, I always paid rapt attention. Our life worked—again, unbearably cliché, but true. I always described our relationship to people that way. “It’s like breathing,” I’d say.

At breakfast, Doug took out the video camera: “It’s September eleventh, do you know what we’re doing today?” The kids giggled and asked Daddy to turn the video screen around so that they could see themselves. He asked them to name their teachers and describe what they looked forward to doing at school. The kids giggled and blew kisses at the camera while I, clad in a frumpy terry cloth bathrobe, scrupulously avoided the lens. Doug swooped over to the stove where I was ladling pancake mix onto a skillet and wrapped his arms around my waist. “I’ll see you tonight for Grandpa’s dinner. It’s going to be great. You’re the one.” My gentle husband of six and a half years—in his new blue shirt—tousled my hair and kissed me good-bye. Michael walked his daddy to the door to press the elevator button as he did every morning. I heard Doug hug his son in a loud squeeze, then Doug was gone.

Gone.

That simple word can be so benign—when someone leaves a room, he’s gone, when your toddler eats her carrots, they’re all gone. Doug went to work and was gone in the usual way. Until he wasn’t. Until that gone became something else entirely, just a few hours later. Gone became “vanished,” “lost,” “evaporated.” It was the worst gone that I’d ever known, and when I replayed it (how many times have I gone back over that morning?), all I can think of is that, if I had it to do over, I’d have dug my fingers into that blue shirt and never let go.

I got Michael ready for school. Forty-five minutes later, we stood in our building’s lobby as I took pictures of my ebullient son grinning in his green, tie-dyed T-shirt and khaki shorts. He grabbed my hand, high-fived the doorman, and we trotted out onto the sunny sidewalk for the short walk around the corner.

When the world fell apart, I was unaware. While downtown burned, I watched Michael work a puzzle in his classroom. I was snapping pictures of him and his teacher when my sitter, Glenda, appeared in the doorway with Julia in her arms. I was later told that Glenda was screaming my name while she was running through the hallways, but I only remember her telling me, “Jen, you need to go home. A plane hit the Trade Center, but Joe [Doug’s dad] said Doug was getting out.” I had no idea what she was saying. I heard her continue, “Go home and call Doug.” I left Glenda with the kids and started to walk down the four flights to the sidewalk. My cell phone wasn’t working, but at that point, I wasn’t worried. What’s the big deal? Some single-engine got misdirected and clipped the tower? I continued to try to reach Doug to no avail as I walked around the corner toward my apartment building. In the lobby, I asked our doorman, Ney, “What’s this about a plane and the Trade Center?” Only when the last word came out of my mouth did I notice Ney’s face. He was ashen, he couldn’t meet my eyes. My stomach turned over. I hurried upstairs, clicked on the television, and watched my life end.

Doug’s colleague, a young manager from Cantor whom Doug mentored, suddenly appeared at my door. He’d bicycled over to wait with me. I took that as a bad sign. It instantly reminded me of movie scenes in which the military officer arrives at the white clapboard house to deliver tragic news about a soldier—the wife knows the minute she sees the dark sedan pull into her driveway; her world collapses without a line of dialogue.

The phone started ringing incessantly. I was standing in our dark kitchen with the breakfast dishes still piled in the sink, talking to Doug’s friend from college, Michael Kaminer. He called from Boston a few moments before I saw the South Tower collapse. On television, the imploding building roared to earth, and I watched a storm of dust and debris belch out of the wreckage. Michael pleaded on the phone through my screams, “What’s going on?”

“He’s dead,” I announced, and hung up. I couldn’t stay on the line another second. Doug was on the 105th floor of the North Tower. It hadn’t yet fallen, but I knew he was gone. I felt him leave me, slam out of my chest like an astronaut hurtling into space with a torn lifeline. Several years later, an audio recording of Doug’s cell phone call to 911 at about the time of the South Tower collapse surfaced and confirmed the accuracy of my experience. A representative from the mayor’s office called to tell me that Doug was one of only a handful of people in the towers identified on the 911 tapes from that day. The city would be sending the tapes to the “next of kin,” but she advised that I, specifically, should not listen to Doug’s recording by myself. She told me that it was “horrific,” and Doug’s voice was “excruciating” to hear. With my heart pounding so loud I could hear it, I asked whether she could send a written transcript so I wouldn’t have to listen to it at all. She replied officiously that the city wasn’t making transcriptions; they were only providing CDs. I couldn’t believe my ears. Was this bureaucrat actually telling me that we would have to pop a disc into a laptop to hear our husbands’ wretched final utterances? I launched into an onslaught of finely articulated fury at the city’s callous lack of judgment: “Do you have any idea the impact this will have on a widow when she receives just a recording without a transcript? How can she not listen to it? You can’t just inflict these tapes upon us without giving us a choice about how we experience them.” The poor woman stuttered and tried to tell me she understood how I felt. “I don’t need your understanding. I need you to tell your supervisors to provide transcripts, or I swear I will call every media outlet in New York and expose the city’s asinine refusal to type a few write-ups so we might not have to hear our husbands’ tortured voices screaming from the grave!” Three days later, the woman called to let me know that written transcripts would be included with the tapes.

I never listened to Doug’s voice. I did read the neatly typed transcript, tentatively, holding the page away from my face at an oblique angle so that my eyes gleaned only a few words at a time. I don’t know for sure, but I think he died on the phone while asking how long it would take for help to arrive. At the end, he was still trying to take care of things. I know some people can’t fathom why, to this day, I’ve never chosen to hear my husband’s last words. But I knew that I could never survive the sound of his suffering. I’d already imagined Doug’s agony and fear a thousand times—I put myself with him, wrapping my body around his in the smoky chaos while the floors collapsed. I eventually locked those replayed scenarios away in a deep corner of my mind. To hear Doug’s voice—his soothing, gravelly baritone distorted into a choked, desperate whisper—would literally destroy me. I gave the tape and transcript to my younger sister, Jayme, to hide them somewhere out of reach. I didn’t want his last words lying around where I could access them in a weak moment.

.....

I spent another few seconds watching the South Tower cave and stumbled my way out of the kitchen into the family room. Sunlight streamed in the side window through the partially closed blinds, the view obstructed by construction scaffolding that felt as if it’d been up forever, as workers repaired the aging façade. I stood there, looking at the happy photographs and children’s books crowding the shelves of the built-in bookcase, at the L-shaped sofa with “Doug’s corner,” where he always stretched out. I remember how bleak the house felt at that moment. With one hand on the couch, I lowered myself to my knees and heard myself say, “Doug’s gone. I’m a widow.” I repeated it, maniacally, like a madwoman, as I dialed Doug’s sister, Danielle, who lived downtown. “My life is over,” I said simply. “Come up here when you can.”

My friend Pamela Weinberg arrived next. She came directly from Stephen Wise where her son, Benjamin, attended with Michael. Pam is one of my closest friends. I met her about five years earlier at a local manicure place on Amsterdam Avenue. We were both pregnant with our sons at the time, and she had just coauthored the first in a series of successful City Baby books and hosted weekly new-mother seminars around Manhattan. Sitting at the nail dryers, we bonded over weight gain, weak bladders, and swollen feet. Our boys were born five weeks apart in the fall of 1996. Pam was the ultimate girly girl. Petite, with long, wavy, light brown hair and the warmest smile, she was the best friend who organized spa days with the girls, cried during romantic comedies no matter how corny, and hosted mother/daughter reading groups in her traditionally appointed home. She brought a Martha Stewart quality to everything she did, minus the New England hauteur. Thank God for Pam. Without her I would never have discovered the frozen yogurt at Bloomingdale’s or learned how to make the perfect spinach dip.

Pam ran to me in the family room, and I felt her arms around me. Her eyes looked wild as they searched my face for news. I told her Doug was dead. She tried calmly to convince me that he might be walking up the West Side Highway with the other survivors. I shook my head and pounded my chest, “He’s dead, Pam. I can’t feel him anymore.”

My parents called from their home in Longmeadow. They could barely speak. My dad’s voice sounded so small to me. My mother told me that they were trying to figure out the fastest way to get to Manhattan. They’d heard that the city had closed all bridges, tunnels, and roads. I told them to come tomorrow—there was nothing they could do now.

Jayme, my only sibling, called from St. Vincent’s hospital on Twelfth Street, where she worked as a pediatric nurse practitioner. Her practice concentrated primarily on treating children and adolescents with HIV/AIDS. As I often said, my sister was a saint, saving the world while I was out to conquer it. Jayme and I were as close as two sisters could be, and she loved Doug as a brother. The two of them were at my side while I gave birth to Michael and Julia, with Jayme cajoling Doug through the process and giving him a strong shoulder on which to lean when his nerves began to fray. From the day our son was born, Doug addressed my sister only as “Aunt Jayme” and counted on her to walk him through every sniffle, cough, bump, and bruise.

Jayme was being held at the hospital to wait for injured victims, but almost no one materialized. No victims. No injuries. Either you got out unscathed or you perished. In or out. Gone or still here. No in-between. She arrived at my apartment in the late afternoon. I hung up the phone and ran back to Stephen Wise, where I’d left the kids. My upstairs neighbor, Margie, was walking through the synagogue’s lobby with her children. I grabbed her by the shoulders and literally barked at her to find Michael and Julia and take them to her apartment. She recoiled, confused by my brusqueness, and told me to calm down, “Easy, we’re all a bit tense right now.” I snapped through clenched teeth, “Margie, it’s Doug!” She’d forgotten my husband worked in the Trade Center. She suddenly looked just like my doorman: stunned, pale, speechless. For months, I would see the same reaction on every face in front of me.

For the next several hours, my home morphed into a command center. In addition to my friends and Doug’s family, who crowded into the apartment to wait with me for news, families and friends of Cantor employees called all day, expecting I’d have answers because Doug was a senior partner. But he wasn’t in charge anymore, and I had no special intelligence just because he’d been the boss. Doug was just as dead as everyone else.

I never understood pacing until I couldn’t stop; all I could manage was to walk from the family room to my bedroom and back. Doug’s father and mother fell into the same tread, shuffling between the living room and family room. Doug’s sister scanned the Internet. Pam made phone calls from the kitchen. No one ate or drank. No one spoke except to offer a theory about how Doug might still be alive. That was one thing I could not handle. Any reference to Doug as “missing” undid me. He was dead. It didn’t help to hypothesize some miraculous escape. I didn’t want to read the hundreds of e-mails with useless updates. “I heard the 86th floor got out.” Doug was on the 105th. “He could be badly burned and unidentified in a hospital in New Jersey.” Impossible. Too many e-mails opened with “Please tell me Doug got out.” I replied to every note or comment the same way: “He’s gone.” All I could focus on was one looming task: how was I going to tell Michael and Julia that Daddy was never coming home?

Each time the phone rang, heads whipped around and everyone stared at me, hoping that Doug was somehow on the line. I answered every call, trying not to allow myself to believe that he was safe. I spoke with several newly minted widows that morning—together, we’d joined a wretched club of which we wanted no part. LaChanze Gooding, the accomplished Broadway actress and wife of Doug’s college pal Calvin, called several times. Her husband worked on the 103rd floor running Cantor’s Emerging Markets division. She and Calvin had been married less than three years, and she was eight months pregnant with their second daughter. I unabashedly adored Calvin. And Calvin loved his friends with unrestrained emotion. He and Doug played basketball together at Haverford and served as ushers at each other’s wedding. His wedding to LaChanze was the most joyous, emotionally effusive event I’d ever attended, complete with African dancers, Ghanaian marriage rituals and impromptu jam sessions by LaChanze’s musically gifted friends. When Calvin and I last spoke, he told me he was writing a hilarious tribute song to perform at Doug’s fortieth birthday dinner celebration. Now, with a deep pit in my stomach, I tried to reassure LaChanze unconvincingly that we would get each other through this. She was certain Calvin was missing, that he might have gotten out of the building. I feared he was as gone as my husband, but I didn’t say anything. I just said that I loved her and whatever happened, Doug and Calvin were together.

The house didn’t stop. Tense conversations in low tones incessantly buzzed. I heard my sister-in-law say that she couldn’t handle looking at the photos of Doug on the walls. Neither could I. There he was, smiling at the camera, cradling a tiny Julia in his large arms or tossing a squealing Michael into the air at the beach. How often have we seen similar photos on newscasts? Murder victims who became smiling snapshots on CNN. Was Doug now just a human-interest story? One of the chilling total killed on a late-summer morning? I retreated to my bedroom in the early afternoon, unable to find a quiet corner anywhere else. Pam stood sentinel at the doorway, allowing visitors to pass at her discretion. I remember sobbing on the shoulder of my cousin when Allison burst through the door.

Allison was married to Doug’s best friend, Howard Lutnick, president and chairman of Cantor Fitzgerald. He survived the attacks that morning because he had taken his oldest son, Kyle, to his first day of kindergarten. The Lutnick and Gardner families were entwined—their children and ours overlapped in ages, and we shared nearly all of our family vacations and holidays together.

I was especially close with Allison, whom I first met on Doug’s thirty-second birthday in 1993, at a Cantor Fitzgerald party at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The party was one in a series of events celebrating the opening of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden, a gift from the founder of Cantor Fitzgerald, Bernie Cantor. Doug and I had been dating for about six weeks. I arrived straight from work, and as soon as we ascended the grand steps on Fifth Avenue leading into the museum, I could tell this was going to be one of those corporate bacchanals that were legendary in New York at that time. The party spilled through the Egyptian gallery into the magnificent Temple of Dendur. Inside, guests shoveled caviar onto toast points from overflowing stations and enjoyed trays of shrimp, Peking duck, and other delicacies I couldn’t afford. The room twinkled with hundreds of candles. Cascading flowers and crystal-laden tables were everywhere. Cantor even hired a limousine service to carry guests home in black town cars after the party. I stood sipping champagne, wearing a well-worn, green Kenar suit picked up at a sample sale, and Nine West black patent leather pumps. Not exactly Cinderella, but I did feel a bit like Dorothy.

We didn’t have caviar, museum openings, or surgically enhanced dowagers flaunting tablespoon-size diamonds in the unassuming neighborhoods of Massachusetts where I was raised. We’d lived a typical, middle-class existence of car pools, basement birthday parties, and family dinners at Friendly’s. My mother taught in the public schools and my father worked in advertising. Our family vacations typically entailed camping, skiing local mountains, or fishing on Cape Cod. Once we took a ten-day trip to Florida, four of which were spent driving from Massachusetts to Orlando and back in a Pontiac Grand Safari station wagon (with the requisite wood paneling on the sides.) I financed my entire law school education at Harvard through two different student loans.

Fashion and style were not part of my vocabulary. Instead of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, I grew up reading Sports Illustrated, Time, and Mad magazine. My underdeveloped sartorial tastes ranged from the Limited to Filene’s Basement. An Ann Taylor suit eventually became the holy grail of my wardrobe, as I stretched my budget to invest in a few proper outfits for law firm interviews and my fledgling career. Still, I didn’t have a clue about style. It got so bad that a paralegal at work, a woman who made half my salary but dressed with a practiced eye, took me to lunch one day for the sole purpose of forcing me to buy two pairs of decent shoes. Then she unceremoniously tossed my cracked, boring pumps in the nearest trash can.

When Howard saw us enter the Temple of Dendur that night, he came straight over with outstretched arms and a big smile. He’d just played golf with Doug and two Knicks basketball players that morning, a gift Howard generously bid on at a charity auction for Doug’s birthday.

Howard Lutnick exudes confidence and brio. He was forced to grow up quickly when his father died of complications from chemotherapy during the first week of Howard’s freshman year at Haverford. Howard’s mother had died the previous year from cancer. At eighteen years old, he and his older sister, Edie (a law student at the time), were orphaned and suddenly responsible for their fourteen-year-old brother, Gary. Who could have predicted that Howard’s early tragedies would serve as a warm-up for the catastrophic events to come?

Eventually, all three siblings finished school and moved to New York for their careers. Howard joined Cantor Fitzgerald as a bond trader and soon became Bernie Cantor’s protégé. Bernie named Howard president of the firm when he was only twenty-nine years old, and Howard has helmed the firm for over twenty years. Howard saw Cantor as an extension of his family and hired his brother to work with him. He recruited his friends (and their friends and family members) because, as he liked to say, “if we’re going to spend so much time working so hard, we might as well do it with people we love.” This made Cantor an attractive environment, but also compounded the tragedy that would come. At least twenty sets of “doubles”—parent/child or sibling pairs—died that day in the North Tower, along with golf foursomes, fishing buddies, and fraternity brothers.

After hugging Doug and clapping him on the shoulder, Howard shook my hand and greeted me with an edgy smile that said, “I’m glad you make my friend happy, but I need to know more.” Howard launched into an interrogation that fell somewhere between playful cocktail chatter and a Star Chamber. I bobbed and parried and hoped I held my own.

Howard walked us over to where his then girlfriend, Allison, was sitting with her parents. Allison stood up, and I felt sure she was the most glamorous woman I’d ever seen. A thick, shiny mane of jet-black hair spilled over her delicate shoulders framing bright eyes, sculpted cheekbones, and glossed lips. She stood before me, lithe and impeccable in designer clothes I couldn’t identify. I felt instantly drab in my green suit as Allison smiled warmly and reached out her elegant hand. Why was I surprised that Howard was dating the Jewish version of a supermodel? To make matters worse, she was sincere, intelligent, and not a lady who lunched: Allison was an accomplished litigator who would soon become a partner at a large insurance defense firm. I tucked my hand under Doug’s arm and tried to stand up straight.

When Doug joined Cantor a few months after the Met party, Allison’s and my lives merged. Howard and Allison got engaged three months before we did. Our weddings were four months apart (they were married at the Plaza, we at the Essex House). We spoke every day and quickly got to where we understood each other without having to complete a sentence. It turned out she and I came from similar backgrounds and struggled with tight budgets like every other new arrival during our first few years in the city. We were both crossing the threshold from girlfriend to wife together and delighted to have a trusted sidekick. Looking back, we had a kind of halcyon routine: The men worked together contentedly, and we coordinated our lives to keep our families together. We attended every Cantor social function together and took joint vacations to Florida, the Caribbean, and Europe. Our first sons were born six months apart and then our second children within a year of each other. Allison and I compiled impressive pregnancy wardrobes, which we stored in plastic boxes by season and shuttled the growing collection back and forth. We found in each other a “secret sharer” when it came to food. Unlike my weight-conscious friends who refused to eat more than a dry salad in public, Allison and I never met a bread basket we didn’t devour. An e-mail of “I’m hungry, where are you?” would prompt an immediate rendezvous at the local diner for tuna melts, or, if we had the time, a favorite Italian place for a more leisurely lunch of rigatoni butera and caprese salad with thick slabs of mozzarella. I happily endured extra hours on the treadmill to pay for these indulgences, but Allison, the genetic miracle, maintained her waiflike figure with nary a sit-up.

Being a Cantor wife was a little like being in The Sopranos. We learned quickly to accept without complaint our husbands’ long hours at work, their overseas business trips and road shows, the curtailed vacations, and the frequent Sunday meetings. Our men were busy, working hard to build their business and share with their families the fruits of their success. Allison and I had an insider’s view of life as a Cantor wife; we were a two-person support group, a loyal partnership through which we could divulge and vent freely in confidence.

Among the four of us, there was no such thing as too much information—the personal details of our marriages that we shared to raucous laughter over late-night drinks might make some shake their heads, but for us, this intimate familiarity was the secret language of our merry foursome. The term happy marriage seems flat or too simple, but it’s apt; it’s what we each had. The Lutnicks and Gardners were happy. Until we were despondent.

When Allison flew into my bedroom that early afternoon of September 11, I knew that I had lost more than Doug. The Gardner/Lutnick balance, our idyllic history, was finished. We were no longer equals; my life had fallen off a cliff while she and her intact family continued to move forward. This altered dynamic rocked our friendship during the next few months, creating for me an unprecedented discomfort and confusion that took time to reconcile.

Allison wrapped herself around me, and we both sobbed into each other’s shoulders, twisting in pain. The only other time I saw her like that was three years prior in the emergency room after Kyle accidentally cracked his head open on their marble floor. We resolved that unfortunate mishap with a few dozen stitches. How would we ever fix this? I noticed that she was wearing running shoes and not her signature heels. Her sneakers were perfectly white and had probably never met the sidewalk, since Allison was not known to jog. “What are those?” I asked, pointing to her unexpected footwear. She looked down. “I ran through Central Park to get here.”

“You ran?”

“The streets are closed. I had to get to you.”

“Where’s Howard? Your sitter told me he was going to the Trade Center.”

“He’s down there. He went straight from Kyle’s school.”

“It’s bad, isn’t it?”

The tears spilled over Allison’s distressed face. “It’s as bad as it can possibly be.”

“I know.” I started to choke again. “What are we going to do?”

No answers, just tears.

Allison left after a while to return to her frightened children. About an hour after she’d gone, Howard walked through the front door, shattered. He was covered in cement dust, dirt, and other matter I didn’t want to investigate. We held on to each other in the foyer for a long time; he repeated in my ear forcefully, “You’ll be fine. I promise, you will be fine!” Neither of us tried to paint an optimistic picture. He’d just had a front-row seat to the North Tower’s collapse. The firm was wiped out in seconds, and Howard’s brother, Gary, who was with Doug at the office that morning, was among the dead. I told my friend I knew we wouldn’t be seeing each other much in the next few weeks; he had a colossal task ahead of him. Howard nodded, “I have to take care of my families.” Cantor lost 658 employees, the greatest toll suffered by any single company that day. Clearly, Howard wasn’t going to have time to mourn his brother and best friend—there was so much loss in front of him and so many decisions.

In the next few weeks, I would see Howard only sporadically, but he called whenever he could grab a few minutes. We talked in the middle of the night or while he was traveling from one deceased employee’s home to another. In some ways, I was Howard’s canary in the coal mine; whatever I was feeling at any given time—fear, insecurity, fury—gave him a vivid picture of how the families were coping. Allison, too, was pulled into the vortex of grieving families and a chaotic household that had transformed into Cantor’s makeshift headquarters. Distraught family members and the press bombarded their phone lines, faxes, and e-mail accounts seeking information about the victims or what Cantor was doing to help. Within a day of the attacks, Allison presciently set up the company’s crisis center at a local hotel, where the families could gather to see Howard and receive whatever bits of information Cantor had. She also recruited friends and volunteers to answer phones, do errands, and organize information at her home, while Howard and his remaining partners struggled to run the firm from the dining room.

Allison called every day, but I knew she was overwhelmed with trying to take care of her husband and the families of so many people she loved and admired. More than anything I wished I could have been more helpful to her, to shoulder half the burden, offer comfort and empathy. But Doug was dead, and I couldn’t see beyond my own suffering. I was helpless and useless. I tried to spend an evening at the crisis center, but the crowds and panicked faces sent me reeling. Allison hurried me out of the ballroom with one arm protectively wrapped around my shoulder and made sure someone took me home. It killed me that I was too weak to be there for her. All I could do was admire her strength under such intense pressure and pray that we would one day find our way back.

After Howard left my apartment, I remembered to call Shun Lee and cancel our dinner reservation and a doctor’s appointment scheduled for Thursday. I actually told the doctor’s receptionist in a strangely calm voice that I couldn’t make it because my husband had just died in the Trade Center. I wondered if she received other similar calls that week. I then asked Jayme to call my neighbor. “Please ask Margie to send the kids home now.” Jayme nodded, the tears forming in her eyes, and I stumbled to the bedroom. I arranged some pillows against the headboard and seated myself on our bed. Our bed. Now it was just mine.

Only a week ago Doug had gathered all of us together right under this comforter upon hearing the news that a local restaurant owner had died in a car accident. Doug declared, “That’s it, no one is ever leaving this bed. We’re going to stay right here forever.” Our bed. Home base. We’re safe. Not anymore. For the next several months I’d sleep, if at all, with my face pressed against my nightstand, turned away from Doug’s side.

Jayme led Michael and Julia into the bedroom. Michael was still wearing his clothes from school. Julia had a big white bow in her hair. Just two mornings ago I found Doug in Julia’s bedroom, sitting on the carpet as he tried to affix one of Julia’s ubiquitous bows to her downy hair. Julia wasn’t cooperating, squirming in his arms and dashing away in sheer delight that Daddy couldn’t catch her. I noticed she had also thrown several dresses and T-shirts out of their drawers onto the floor. Doug looked at me helplessly amid the detritus of our toddler’s reverie. With an exaggerated frown on his face, he whimpered, “Honey, our daughter refuses to get dressed.”

“Douglas,” I said, trying not to laugh at the precious scene. “You’re the adult. Who’s in charge here?”

He looked admiringly at his cackling daughter and pointed. “She is. I’m just a toy.”

Could it have been two days ago? Now, these two wide-eyed, giggly babies climbed over me and settled under my arms. I didn’t want to see their bright little faces go dark. I hugged and kissed them for a while, holding them close and inhaling their sweetness as if I were taking in my last breaths before drowning. Michael said, “Grandma is in the living room.” I looked down at his curious brown eyes and said, “I have to tell you something important.” I fought the lump growing in my throat. “There was a big explosion at Daddy’s office building. It was very bad, and we can’t find Daddy.” Julia played with my hair. Michael’s brown eyes grew wide. He asked me if Daddy got out. “I don’t think so, Michael. Daddy is very strong and he tried really hard, but I think it was just so bad and sudden and he didn’t have time.” Michael looked up at me and said, “I’m going to sit with Grandma.”

My in-laws left the apartment when it was dark. I did that pacing thing again through the house with my sister for several hours. Glenda, our sitter, fed the kids dinner and turned on Blue’s Clues. I tried to bathe Michael and Julia at bedtime, but Jayme had to finish the task. I didn’t have the strength or the smiles, and I didn’t want them to feel the weight. My mind raced, making it impossible to sit still. My skin felt tight and ill-fitting, like a scratchy wool dress on a hot day. I looked out our second-story window at a dark and eerily deserted Central Park West. Only a few cars passed. On many warm nights Doug would call from the back of a taxi on his way home from work and ask me to bring the kids to the front window. I would hold Michael and Julia in their pajamas up to the glass and say, “Let’s look for Daddy!” We would count yellow cabs until one would stop across the street, and Doug would emerge with his heavy briefcase under the street lamp. The kids would shout for Daddy through the plate glass, and Doug would look up in mock surprise, blow kisses, and dash inside. Now, our treasured routine was just a memory, one in a sea of moments big and small that we would never be able to share again.

I don’t even remember if I put the kids to bed that night—I think Jayme did it because I was shaking too much. My sister helped me get ready for bed. I didn’t want to get undressed. If I took off my clothes, the day would be over, the possibility of a different ending extinguished. Doug always came home at the end of the day. What happened to him?

I couldn’t breathe. I ranted to Jayme that I wished it were a year from now. “A year from now it has to be better, right? I can’t do this. I can’t feel like this for another minute. Please, just make it a year from now.” I wanted to get out of my skin, to shed the day’s horror and escape back to yesterday. I wanted Doug to come home, to hear the front door open and the sound of change clattering onto the foyer table. I sent Doug an e-mail—“I love you. You did everything right.”

Jayme slept next to me. I don’t think I slept much, but when I did, terrifying images of burning buildings and stampeding crowds hurled through my brain. My body continued to tremble and the painful hole in my stomach expanded. I spent the predawn hours sitting next to Michael’s bed on his blue carpet staring at the painted baseball knobs on his white bureau. When I heard him stir around 6:00 a.m., I sat down on his comforter with the dancing teddy bears and waited for him to open his eyes. I knew it was coming. “Did Daddy come home?” I told him no. He sat up and said, “Mommy, maybe he couldn’t come home because the streetlight broke. Maybe the light won’t change to green, and Daddy can’t cross the street.” I got Michael dressed and took him with his bicycle across the street to the parking lot of Tavern on the Green. Doug had recently taught him to ride a two-wheeler—an accomplishment about which Doug proudly boasted to anyone within earshot. Michael rode around me in a silent circle for a while and then stopped. “Maybe the plane flew too low because a stewardess tripped when she served the food, and the pilot tried to help.” I explained to him that bad people were flying the plane, and that this was not an accident. “Was Daddy running when he tried to get out? Did he try to jump out of the way?” I told him that the explosion was too powerful, and Daddy’s office was too high. Michael looked up at me and said, “I think Daddy died.”

Michael and I visited Tavern on the Green’s parking lot for the next three mornings. He would ride, I would answer. Sometimes he would tell me, “I’m strong, Mommy. I could have gotten out.” He wanted to know why Daddy didn’t jump, or why no ladder was outside his window. He reassured himself, “Airplanes can’t hit our building because we live on the second floor, right?” He sounded as if he could have been asking why birds fly or why the sky is blue. Except, in this case, I didn’t have any intelligent answers. Mommy and Me classes don’t teach you how to explain to a five-year-old that Daddy was murdered in his office by terrorists. I knew instinctively, however, that my son needed the facts without adornment. He needed to know that Daddy would never leave us on purpose, he was taken away unfairly. I just explained, “Daddy didn’t have time, he tried really hard to come home to us, and we’re proud of him.”

.....

The days and weeks following Doug’s death moved at an unbearably slow pace. It wasn’t easy for me to make sense of my new status. I am Jennifer Gardner, Doug Gardner’s wife. I was Doug Gardner’s wife. I’m still his wife, but he’s dead. I’m single, but I’m married. I’m married, but I have no husband. Doug was my husband, but he’s gone. I’m a widow. What is that? Widow… widow… widow… that word pervaded my thoughts like an insidious virus. Widow-maker, widow’s walk, widow’s peak, black widow, The Merry Widow. The dictionary defines widow as “to separate, to divide.” That’s true. I was, unquestionably, irrevocably separated and divided from the beautiful life we’d had before. From now on, my life would be demarcated with a Before and After; every memory tagged with one of those distinct labels. Could I really be a widow so soon? For me, widow was just the last box on a medical form at the doctor’s office: Single, Married, Separated, Divorced, Widowed. Widowed is always listed last because who the hell is widowed? I never really noticed that word, but now it was as if it were flashing in neon wherever I turned.

Who is a widow? An ancient Italian woman from the Godfather movies dressed in black under a veil? World War II wives in shirtwaist dresses receiving horrible news via telegram? The kaffeeklatsch of Jewish ladies in Boca playing canasta? How can this term possibly apply to me? I was a thirty-five-year-old lawyer raising two small children on the Upper West Side. I’m happily married, for God’s sake. I was definitely not going to get through this.

At least I wasn’t alone in Widowville. Turning on the television, I could see that, post-9/11, widows weren’t such a rare commodity anymore. No longer were we hidden away, only venturing out in the company of girlfriends. We weren’t required to raise our children dutifully while maintaining a quiet distance from the world. Instead, widows were on every talk show and news update, petitioning Congress and City Hall to preserve, redesign, or sanctify Ground Zero. Apparently, we were a hot trend, the new black. We had cachet—at least as far as the media and politicians were concerned. Paraded around State of the Union addresses, honored at charity functions, and remembered at Super Bowl games, the 9/11 widows became every politician’s or social climber’s favorite accessory.

I didn’t have the strength to join the fight for better security measures or a proper memorial at Ground Zero. Thankfully, other brave families did. I knew myself. I’d have pursued the cause single-mindedly and would never have been able to extricate my soul from a bottomless pit of fury and despair. I feared I’d lose myself in the process and diminish Doug if I focused on how he died instead of remembering how he lived. I could neither live at his grave nor attempt to achieve mythical “closure” and move on; how I lived without Doug would never be a black-or-white proposition. I needed not to choose and simply try to muddle through the gray.

Although I avoided most of the media frenzy, I did receive my share of sideshow curiosity from the sympathetic but ever-inquisitive young mothers swirling about the Upper East and West Sides of Manhattan. I’ve been pointed out at my children’s school and whispered about at the gym or on the street: “That’s her over there. That one, she lost her husband on 9/11. I like her shoes.” No one meant any malice by it, of course. I was just a marked woman, the girl sporting the Scarlet W on her chest. I was visible, useful social currency to be exchanged over manicures or lunch at Saks. I was the embodiment of everyone else’s fears. There but for the grace of God go I.

The media feasted on every detail of the catastrophe. Protecting the kids from the violent images became my full-time job. The news constantly replayed the moments the planes struck the buildings. We perused daily the New York Times section, “A Nation Challenged,” for those who perished so that Michael and Julia could see they were not the only ones to lose a daddy. Every morning we read the short biographical stories under each victim’s picture. Michael memorized the names of all the companies that lost employees. We identified Daddy’s close friends who died with him—Calvin Gooding, Gary Lutnick, Greg Richards, Joe Shea, Andy Kates, Fred Varacchi, Jeff Goldflam, Dave Bauer, Eric Sand, Doug Gurian. Sadly, there were hundreds more friends and colleagues to count. After a few weeks of our morning routine, every time Julia saw a headshot in the newspaper, she asked if the person had died.

Michael began to own the story of his father’s death. He told his friends what happened, repeating the words that I had spoken to him. At school, Benjamin Weinberg, Pam’s son, attached himself to Michael. Wherever Michael turned, Benjamin, like a tiny Secret Service agent, was at his side. He made sure that the other children didn’t raise the subject unless Michael wanted to talk about it. Once, when the students were painting on a table covered with used newspapers, Michael saw a photograph of a billboard that displayed the names of some of the victims. Shockingly, he saw his father’s name on the billboard and pointed it out to his classmates. Some of the children tried to argue with Michael, insisting that his dad didn’t die. Benjamin shielded him and stopped the other kids’ challenges. To this day, Benjamin and Michael are inseparable.

.....

On the one-year anniversary of Doug’s death, Michael attended his first day of kindergarten at Riverdale Country School, a private school in the Bronx just north of Manhattan. Doug had graduated from Riverdale in 1979 and decreed to me that his children would continue the Gardner legacy at his alma mater. Although he good-naturedly permitted me to explore other schools in the city, he’d already decided his children would be Riverdalians. Indeed, on our spring tour, Doug delighted in pointing out his former hangouts and the locations where he suffered his various injuries, including a low ceiling on which he banged his head, and the nurse’s office where Nurse Boyle once diagnosed him with appendicitis. As with most things, Doug was right about Riverdale. It was a beautiful school nestled on several acres of green fields and mature trees. The school reminded me of a small college campus, but with playground equipment and children’s artwork taped in each window. Doug couldn’t wait for his children to sit in the same classrooms and walk the same halls he did as a student. We mailed Michael’s application to Riverdale the weekend before the attacks.

New York private schools conduct interviews with applicants and their families in the fall before making enrollment decisions. I knew I couldn’t handle those interviews, waiting alone, the weepy widow, alongside well-coiffed couples holding hands and watching overdressed four-year-olds smile stiffly for the admissions officers. I also started fretting about sending Michael to school in the Bronx; Riverdale was too far outside Manhattan and I worried about reaching him if there was another attack. Just a few weeks after 9/11, Pam arranged an interview for Michael at Dalton, her daughter’s school on the Upper East Side, which was a mere cab ride from my apartment. She told my story to Dalton’s head of admissions, Elizabeth Krents, and explained that I was having second thoughts about sending Michael to his father’s school. Ms. Krents graciously allowed me to sob on her couch for a half hour while Michael met with the admissions staff. She told me to stay in touch in case I decided against Riverdale.

When it came time for Michael to have his interview at Riverdale, Doug had been gone for just two months. Walking alone with my child up the leafy path from the parking lot to the admissions building took every ounce of strength I had. The receptionist ushered Michael into an office where Dan DiVirgilio, the admissions director, welcomed him with a big smile. Everyone knew our story, but thankfully no one said a word while I waited on the couch outside the office. After ten minutes, Mr. DiVirgilio called me in. A rumpled older man with intelligent eyes and a benevolent smile, he offered me a seat on the leather chair across from his desk. While Michael played with an abacus in the corner, he asked me how I was coping. Big mistake. The façade cracked and choked sobs burst out, causing the poor man to dive for the Kleenex box and wait uncomfortably while I regained a modicum of composure. He told me what a beautiful and intelligent boy Michael was and assured me that he was a good fit with Riverdale. I was distraught. How could I sit there talking about our son’s education at Doug’s school without Doug? The interview process was too much for me; I begged Mr. DiVirgilio to make a decision soon so that I could be done with this agonizing and lonely ordeal.

Two weeks later, I received a call from Riverdale that Mr. DiVirgilio had died suddenly of a heart attack. Of course he did. In the absurd world in which I now lived, why wouldn’t my son’s interviewer drop dead right before admissions decisions were made? I half-expected boils and dead livestock next. What’s worse, my first panicked thought was not “How sad” but “Please, God, tell me he took notes.” I suppressed my alarm long enough to offer hurried condolences to the voice on the other end of the phone—silently begging Michael to forgive me for being a heartless mother—and then asked, “I know this may seem rather self-centered at a time like this, but do Michael and I have to go through this process again? Did he take enough notes for you to make a decision?” I never told Michael what happened, but Riverdale accepted him soon after, and Doug’s son joined the class of 2015.

It was nearly unbearable to walk Michael across campus without Doug, a year after the attacks, that precarious first day. Another missed first day of school in a long line of missed milestones to come. They didn’t get easier as time passed—Michael’s first basketball game, Julia’s school plays, birthdays, Thanksgivings, fifth-grade graduation, a bar mitzvah—each moment a joyous occasion, but etched with the pale reminders of an absent father. As we walked to Michael’s classroom together, I worried about how strangers would treat him, how Michael would handle being the only child at the school at the time who had lost a parent in the World Trade Center. Moms and dads sat together with their cameras in the back of the classroom as Ms. Mahony, the kindergarten teacher, greeted her new students. I sat with my mother, and we both held our breath.

A moment of silence marked the moment when the North Tower was struck for the first time. Not surprisingly, the school psychologist positioned himself in our classroom. I fought to restrain my tears so that I could watch my son’s reaction to the first public acknowledgment of his father’s death. All eyes were on Michael. Suddenly, my little boy sat up straight and declared in a clear voice, “My daddy died on 9/11. Two planes hit the building. He tried to get out, but he didn’t have time. My daddy is one of the heroes, and we’re proud of him.” As the teacher picked herself off the floor and the moms dabbed at their running mascara, my child happily plopped himself down in the block area to build a tower with his new classmates.

© 2011 Jennifer Gardner Trulson

Recenzii

"In this hard-hitting memoir, a wife and mother stricken by tragedy after losing her husband at the World Trade Center gradually regains her ability to love. A former lawyer married to Douglas Gardner, a financial broker, and living with their two small children on Central Park West in Manhattan, Trulson was shuttling her five-year-old son to his first day of school on the morning of September 11. Her husband was already in his office at Cantor Fitzgerald on the 105th floor of the North Tower, where he died in the attacks. (His voice was identified on a 911 tape later sent to Trulson by the mayor’s office, but she never listened to it.) The brokerage firm lost 658 employees that day, the hardest hit of any single company. The closest friends who supported Trulson in her grief were her husband’s professional colleagues, who dedicated a sports center at Douglas’s alma mater, Haverford College. Trulson’s period of “bottomless fury and despair” was exacerbated by the ensuing media circus as she made the rounds of memorial speeches. Ten months later, Trulson became involved with another man, which jars the reader, but, in the end, her narrative achieves a balance between grief and life-affirming determination." —Publishers Weekly

"Decades from now, when people want to know how life went on after the September 11th attacks, I hope they'll turn to this deeply moving, bluntly honest, elegantly written memoir. In Jennifer Gardner Trulson's grief, and in her account of the love that followed, all of us can see the possibilities in our own lives." —Jeffrey Zaslow, coauthor, The Last Lecture

Descriere

An extraordinarily powerful account of hardship and healing by a woman whose husband, a top executive at Cantor Fitzgerald, was killed in the attacks on the World Trade Center, and her unexpected journey to find love again.

Lucky—that’s how Jennifer would describe herself. She had a successful law career, met the love of her life in Doug, married him, had an apartment in New York City, a house in the Hamptons, two beautiful children, and was still madly in love after nearly seven years of marriage. Jennifer was living the kind of idyllic life that clichés are made of.

Until Doug was killed in the attacks on the World Trade Center, and she became a widow at age thirty-five—a “9/11 widow,” no less, a member of a select group bound by sorrow, of which she wanted no part. Though completely devastated, Jennifer still considered herself blessed. Doug had loved her enough to last her a lifetime, and after his sudden death, she was done with the idea of romantic love—fully resigned to being a widowed single mother . . . until a chance encounter with a gregarious stranger changed everything. Without a clue how to handle this unexpected turn of events, Jennifer faced the question asked by anyone who has ever lost a loved one: Is it really possible to feel joy again, let alone love?

With unvarnished emotion and clear-eyed sardonic humor, Jennifer tells an ordinary woman’s extraordinary tale of unimaginable loss, resilience, friendship, love, and healing—which is also New York City’s narrative in the wake of September 11. Where You Left Me is an unlikely love story, a quintessentially New York story—at once Jennifer’s tribute to the city that gave her everything and proof that second chances are possible.