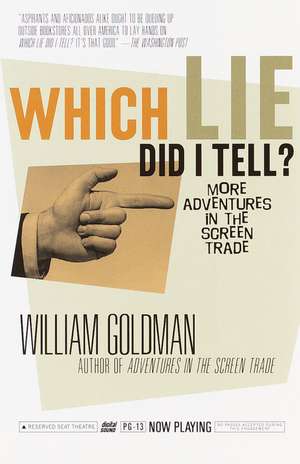

Which Lie Did I Tell?: More Adventures in the Screen Trade

Autor William Goldmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2001

If you want to know why a no-name like Kathy Bates was cast in Misery-it's in here. Or why Linda Hunt's brilliant work in Maverick didn't make the final cut-William Goldman gives you the straight truth. Why Clint Eastwood loves working with Gene Hackman and how MTV has changed movies for the worse-William Goldman, one of the most successful screenwriters in Hollywood today, tells all he knows. Devastatingly eye-opening and endlessly entertaining, Which Lie Did I Tell? is indispensable reading for anyone even slightly intrigued by the process of how a movie gets made.

Preț: 116.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 174

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.25€ • 23.34$ • 18.52£

22.25€ • 23.34$ • 18.52£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375703195

ISBN-10: 0375703195

Pagini: 512

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375703195

Pagini: 512

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

William Goldman has been writing books and movies for forty-five years. He has won three Lifetime Achievement awards for screenwriting, two Screenwriter of the Year awards, two Academy Awards (for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President's Men), and one English Academy Award. His novels include Marathon Man, which has made him very famous in dentists' offices around the world, Boys and Girls Together, The Temple of Gold, and The Princess Bride. He lives in New York City.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Leper

[1980-85]

I don't think I was aware of it, but when I started work on Adventures in the Screen Trade, in 1980, I had become a leper in Hollywood.

Let me explain what that means: the phone stopped ringing.

For five years, from 1980 till 1985, no one called with anything resembling a job offer. Sure, I had conversations with acquaintances. Yes, the people whom I knew and liked still talked to me. Nothing personal was altered in any way.

But in the eight years prior to 1978, seven movies I'd written were released. In the eight years following, none.

I talked about it recently with a bunch of young Los Angeles screenwriters, and what I told them was this: If I had been living Out There, I don't think I could have survived. The idea of going into restaurants and knowing that heads were turning away, of knowing people were saying "See him?--no, don't look yet, okay, now turn, that guy, he used to be hot, can't get arrested anymore," would have devastated me. In L.A., truly, there is but one occupation, the movie business. In New York, the infinite city, we're all invisible.

Example: my favorite French bistro is Quatorze Bis, on East Seventy-ninth. Best fries in town, great chicken, all that good stuff. Well, I was there one night last year when another guy came in, and we had each won two Oscars for screenwriting, and we lived within a few blocks of each other--

--and we had never met. (It was Robert Benton.)

Impossible in Los Angeles. But that kind of thing was my blessing during those five years.

My memory was that the leprosy didn't really bother me. I asked my wonderful ex-wife, Ilene, about it and she said: "I don't think it did bother you, not being out of Hollywood, anyway. But one night I remember you were in the library and you were depressed and I realized it was the being alone that was getting to you. You always enjoyed the meetings, the socialness of moviemaking. You were always so grateful when you could get out of your pit."

I wrote five books in those five years (couldn't do it now, way too hard) and then the phone started ringing again.

This is why it stopped in the first place.

There is a famous and amazingly racist World War I cartoon that showed two soldiers fighting in a trench. One was German, the other an American Negro who had just swiped at the German's throat with his straight razor. (When I say racist, I mean racist.) The caption went like this:

German Soldier: You missed.

American Soldier: Wait'll yo' turn yo' head.

The point being, in terms of my screenwriting career, I never turned my head. Looking back, there was no real reason to. I was on my hot streak then. I was a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval in those years. Between '73 and '78 this is what I wrote:

Three novels:

The Princess Bride (1973)

Marathon Man (1974)

Magic (1976)

And six movies:

The Great Waldo Pepper (1975)

The Stepford Wives (1975)

All the President's Men (1976)

Marathon Man (1976)

A Bridge Too Far (1977)

Magic (1978)

If you had told me, that 1978 November day when Magic opened, that it would be nine years before my next picture appeared, I doubt I would have known what language you were speaking.

It wasn't as if I'd stopped writing screenplays after Magic. But the lesson I was about to learn was this: studios do not particularly lose faith in a writer if a movie is terrible. Producers do not forget your name if a movie loses lots of money. Because most studio movies lose lots of money (they survive on their hits). If, say, they chose directors who had only hits, they would be choosing from a practically nonexistent list. All anybody wants, when they hire you, is this: that the movie happen.

The change came after A Bridge Too Far.

Joseph E. Levine, the producer of that film, thought of me as a kind of good luck talisman. His career was not exactly rocketing the years before Bridge, and when that movie brought him back close to the fire, he attributed a lot of it to me. And he wanted to go into business with me. He bought my novel Magic, made that movie, and then proposed a three-picture deal: I would write three original screenplays for him, pretty much of my own choosing. I had never signed a multiple deal before, never thought I would. But I jumped at it. The work experiences with him had been so decent, unlike a lot of the standard Hollywood shit we all put up with.

One thing that made Mr. Levine unique was that he was the bank. He made his movies with his own money, took no studio deals until late in the game, when he had something to show. He was gambling that he would find movie studios who would want to buy, and he had gotten rich that way. Bridge had cost him $22 million. An insane gamble in today's world, nuttier back then. But the day it opened it was $4 million in profit. Mr. Levine sold the movie everywhere, Europe, Asia, country by country, territory by territory; he had collected $26 million by opening day.

Typical of his bravery was one day when he was in a hospital in New York after surgery. I was visiting him, and the director, Richard Attenborough, called from Holland. They were shooting the crucial parachute drop, and the weather had been dreadful. The parachutists were willing to work the next day, a Saturday.

Attenborough requested that extra day. It would cost Levine seventy-five thousand of his own dollars. Levine screamed at Attenborough for even suggesting such a thing. Attenborough repeated his request. Levine asked if he had sufficient footage for the sequence as it was. Attenborough said he had more than enough but it was all drab-looking. Levine screamed at him again. It was a ridiculous request. Attenborough held tough, saying the extra day might make all the difference. Levine then asked what was the weather report for Saturday. Attenborough admitted it was for more of the same: dreary.

Now Levine really let fly. You limey bastard, on and on, and he finally hung up on Attenborough. But not before he agreed to the extra day. The weather turned glorious and almost the entire wonderful drop sequence comes from that extra day.

Try getting a studio to do that.

So the fact that Mr. Levine did not need studio backing, that he cared not at all for studio money or thinking, was a huge factor in my agreeing to the three-picture deal.

It turned out to be a huge contributor to my downfall.

The Sea Kings was the first of the three-picture deal. A pirate flick. Came from a great snippet of material. In the early 1700s, the most famous, and most lethal, pirate was Blackbeard. At the same time, living on the island of Barbados, was a fabulously wealthy planter, Stede Bonnet.

Bonnet had been a soldier but had never seen action. He had a monstrous wife. Had almost died the previous winter. And, in a feat of great lunacy unmatched just about anywhere on earth, Bonnet decided to become a pirate. He commissioned a ship--the only such one in history, by the way. Pirate ships were always stolen.

So off he sailed.

And met, for a blink, Blackbeard.

They did not sail together for very long, but the idea of these two strange and remarkable men knocked me out. So I wrote The Sea Kings about them. (Butch and Sundance on the high seas, if you will.)

The decision that I made was this: Bonnet, rich beyond counting and miserably unhappy, a student of piracy, wanted one thing more than any other: an adventure-filled life (and if that included death, so be it). Blackbeard was sick up to here with his adventure-filled life. Piracy was getting tougher and tougher, and he was broke, as all pirates (save Bonnet) were. What he wanted was a long, comfortable life and a sweet death in bed.

So I wrote a movie about two men who were each other's dream.

It was filled with action and blood and double crosses and I hoped a decent amount of laughter. When I was done, I gave it to Mr. Levine.

Who just loved it.

The Year of the Comet was my second original, a romantic thriller, about a chase for the world's greatest bottle of wine, and you can read all about it in the chapter with its name on it. I will add only this here--

--Mr. Levine loved it too.

I wrote the part of Blackbeard for Sean Connery, and Mr. Levine got the idea of casting the two James Bonds, having Roger Moore play the more elegant Bonnet. Another casting notion was the two Moores: Dudley (10 had happened) as Bonnet, Roger shifting over to Blackbeard.

In the wine movie, he wanted Robert Redford in the Cary Grant part.

Obviously, you did not see these movies.

What happened?

When Mr. Levine had come to me for A Bridge Too Far, he was pushing seventy, and he hated being out of the loop, was willing to take almost any gamble. Now that Bridge and Magic had helped restore him, his needs were lessened.

He was also older now.

But most critical: the price of movies had begun to skyrocket. So the fact that he was his own bank, so wonderful earlier, was now a huge problem--he was rich, but not that rich. Some research was done on the cost of constructing that everyday little item, the pirate ship.

You don't want to know.

Stars' salaries.

You don't want to know.

He had chances to lay the scripts off to studios but he couldn't do that, y'see, because then he'd be just like everybody else, taking shit from the executives. When he was the bank, he gave shit. I heard him blow studio heads out of the water. I saw him sit at his desk, smiling at me, while he hurled the most amazing insults at these Hollywood powers--

--and they had to take it--

--because he had movies they wanted.

That was the fucking staff of life for the old man. His ego would not allow him to be just like everybody else. He didn't need it.

So both scripts just lay there. (They very well may have been unusable scripts--always a very real possibility when I go to work--but that was not the governing principle here.) I never wrote the third original--Mr. Levine and I parted company.

I was O for two.

The Ski Bum began as an article in Esquire by Jean Vallely. Briefly, it concerned a ski instructor in Aspen who led a very glamorous life. Wealthy and famous clients, the kind of romantic existence most of us only moon about.

That's by day.

By night he was aging, broke, scraping along in a trailer with a wife and little kid.

I thought it would make a terrific movie.

The producer had bought the underlying rights. I signed on, went to Aspen, noodled around, did my research, went to work on the screenplay. Got it to the producer and the studio, Universal.

The producer loved it.

Alas, Universal's studio head hated it. When the producer left for another studio, he asked to buy it back, take it with him. Universal said, no conceivable way. We hate this piece of shit and we are going to keep it forever, thank you very much.

I always thought that was strange. If you hate something so much and you're offered a fair price to unload it, why keep it around? I did know, of course, the most usual reason--fear of humiliation. What if a studio gives up a piece of material that turns into Home Alone (happened) or E.T. (happened)?

But this was all company stuff, taking place far far above my head.

Dissolve, as they say (they really do), Out There.

It's a couple of years later and another executive has come to power at Universal. The guy who hated it so much is still above him, but this secondary power likes the screenplay and wants to see the movie made. We met and his first words to me were these: "You don't have the least idea what happened, do you?"

I didn't then.

I do now.

The producer had been, at the time, relatively new in the picture business. But he was a gigantic figure in the music business: Name a superstar singer, he handled him.

Well, Universal owned an amphitheater and needed talent to fill it. So the very great Lew Wasserman made a deal personally with the producer to handle the amphitheater and also have a movie-producing deal. Anything he wanted to make was an automatic "go."

With one teensy proviso: it had to cost less than an agreed-upon amount. Anything that cost more, Ned Tanen, the head of Universal Pictures, would have to agree to.

The Ski Bum, which needed stars and snow and all kinds of other expensive stuff, obviously needed Tanen's okay.

This presented kind of a problem for the picture because, decades ago, Tanen and my guy had been together in the mailroom at William Morris, where so many great careers were launched.

And they had hated each other with a growing passion since then.

Not only that, Tanen was pissed that the producer had gotten a movie deal at his company by going over his head to Wasserman.

So there it was.

Tanen, of course, rejected it. And, of course, rejected any attempt to buy the screenplay back.

The new executive and I tried an end run. Tanen never budged.

O for three.

The Right Stuff came next. A ghastly and depressing saga (recounted in magnificent detail in Adventures in the Screen Trade, so I won't repeat it here). I left the project angry and frustrated. These were bad times in America--the hostages had just been taken in Iran--so I had wanted to write a movie that might have a patriotic feel. The director wanted something else.

O for four.

On Wings of Eagles was not called that when I got involved. The famous Ken Follett book and the miniseries were still in the future.

But Ross Perot, who controlled the material, was interested in mak-ing a movie about the wonderful time when he masterminded breaking his employees out of an Iranian prison. I still had my patriotic need. I signed on.

The problem with this material was always very simple: it was an expensive action film but the star, the main guy, Perot's hero, "Bull" Simons, was not a young man. And Perot would never have betrayed the basic reality by allowing a younger man to do it.

There was only Eastwood. Had to be Eastwood. No one else but Eastwood. Dead in the water without Eastwood.

He took another military adventure movie, Firefox.

I was the one dead in the water now.

Until late in 1986, when the telephone rang . . .

From the Hardcover edition.

[1980-85]

I don't think I was aware of it, but when I started work on Adventures in the Screen Trade, in 1980, I had become a leper in Hollywood.

Let me explain what that means: the phone stopped ringing.

For five years, from 1980 till 1985, no one called with anything resembling a job offer. Sure, I had conversations with acquaintances. Yes, the people whom I knew and liked still talked to me. Nothing personal was altered in any way.

But in the eight years prior to 1978, seven movies I'd written were released. In the eight years following, none.

I talked about it recently with a bunch of young Los Angeles screenwriters, and what I told them was this: If I had been living Out There, I don't think I could have survived. The idea of going into restaurants and knowing that heads were turning away, of knowing people were saying "See him?--no, don't look yet, okay, now turn, that guy, he used to be hot, can't get arrested anymore," would have devastated me. In L.A., truly, there is but one occupation, the movie business. In New York, the infinite city, we're all invisible.

Example: my favorite French bistro is Quatorze Bis, on East Seventy-ninth. Best fries in town, great chicken, all that good stuff. Well, I was there one night last year when another guy came in, and we had each won two Oscars for screenwriting, and we lived within a few blocks of each other--

--and we had never met. (It was Robert Benton.)

Impossible in Los Angeles. But that kind of thing was my blessing during those five years.

My memory was that the leprosy didn't really bother me. I asked my wonderful ex-wife, Ilene, about it and she said: "I don't think it did bother you, not being out of Hollywood, anyway. But one night I remember you were in the library and you were depressed and I realized it was the being alone that was getting to you. You always enjoyed the meetings, the socialness of moviemaking. You were always so grateful when you could get out of your pit."

I wrote five books in those five years (couldn't do it now, way too hard) and then the phone started ringing again.

This is why it stopped in the first place.

There is a famous and amazingly racist World War I cartoon that showed two soldiers fighting in a trench. One was German, the other an American Negro who had just swiped at the German's throat with his straight razor. (When I say racist, I mean racist.) The caption went like this:

German Soldier: You missed.

American Soldier: Wait'll yo' turn yo' head.

The point being, in terms of my screenwriting career, I never turned my head. Looking back, there was no real reason to. I was on my hot streak then. I was a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval in those years. Between '73 and '78 this is what I wrote:

Three novels:

The Princess Bride (1973)

Marathon Man (1974)

Magic (1976)

And six movies:

The Great Waldo Pepper (1975)

The Stepford Wives (1975)

All the President's Men (1976)

Marathon Man (1976)

A Bridge Too Far (1977)

Magic (1978)

If you had told me, that 1978 November day when Magic opened, that it would be nine years before my next picture appeared, I doubt I would have known what language you were speaking.

It wasn't as if I'd stopped writing screenplays after Magic. But the lesson I was about to learn was this: studios do not particularly lose faith in a writer if a movie is terrible. Producers do not forget your name if a movie loses lots of money. Because most studio movies lose lots of money (they survive on their hits). If, say, they chose directors who had only hits, they would be choosing from a practically nonexistent list. All anybody wants, when they hire you, is this: that the movie happen.

The change came after A Bridge Too Far.

Joseph E. Levine, the producer of that film, thought of me as a kind of good luck talisman. His career was not exactly rocketing the years before Bridge, and when that movie brought him back close to the fire, he attributed a lot of it to me. And he wanted to go into business with me. He bought my novel Magic, made that movie, and then proposed a three-picture deal: I would write three original screenplays for him, pretty much of my own choosing. I had never signed a multiple deal before, never thought I would. But I jumped at it. The work experiences with him had been so decent, unlike a lot of the standard Hollywood shit we all put up with.

One thing that made Mr. Levine unique was that he was the bank. He made his movies with his own money, took no studio deals until late in the game, when he had something to show. He was gambling that he would find movie studios who would want to buy, and he had gotten rich that way. Bridge had cost him $22 million. An insane gamble in today's world, nuttier back then. But the day it opened it was $4 million in profit. Mr. Levine sold the movie everywhere, Europe, Asia, country by country, territory by territory; he had collected $26 million by opening day.

Typical of his bravery was one day when he was in a hospital in New York after surgery. I was visiting him, and the director, Richard Attenborough, called from Holland. They were shooting the crucial parachute drop, and the weather had been dreadful. The parachutists were willing to work the next day, a Saturday.

Attenborough requested that extra day. It would cost Levine seventy-five thousand of his own dollars. Levine screamed at Attenborough for even suggesting such a thing. Attenborough repeated his request. Levine asked if he had sufficient footage for the sequence as it was. Attenborough said he had more than enough but it was all drab-looking. Levine screamed at him again. It was a ridiculous request. Attenborough held tough, saying the extra day might make all the difference. Levine then asked what was the weather report for Saturday. Attenborough admitted it was for more of the same: dreary.

Now Levine really let fly. You limey bastard, on and on, and he finally hung up on Attenborough. But not before he agreed to the extra day. The weather turned glorious and almost the entire wonderful drop sequence comes from that extra day.

Try getting a studio to do that.

So the fact that Mr. Levine did not need studio backing, that he cared not at all for studio money or thinking, was a huge factor in my agreeing to the three-picture deal.

It turned out to be a huge contributor to my downfall.

The Sea Kings was the first of the three-picture deal. A pirate flick. Came from a great snippet of material. In the early 1700s, the most famous, and most lethal, pirate was Blackbeard. At the same time, living on the island of Barbados, was a fabulously wealthy planter, Stede Bonnet.

Bonnet had been a soldier but had never seen action. He had a monstrous wife. Had almost died the previous winter. And, in a feat of great lunacy unmatched just about anywhere on earth, Bonnet decided to become a pirate. He commissioned a ship--the only such one in history, by the way. Pirate ships were always stolen.

So off he sailed.

And met, for a blink, Blackbeard.

They did not sail together for very long, but the idea of these two strange and remarkable men knocked me out. So I wrote The Sea Kings about them. (Butch and Sundance on the high seas, if you will.)

The decision that I made was this: Bonnet, rich beyond counting and miserably unhappy, a student of piracy, wanted one thing more than any other: an adventure-filled life (and if that included death, so be it). Blackbeard was sick up to here with his adventure-filled life. Piracy was getting tougher and tougher, and he was broke, as all pirates (save Bonnet) were. What he wanted was a long, comfortable life and a sweet death in bed.

So I wrote a movie about two men who were each other's dream.

It was filled with action and blood and double crosses and I hoped a decent amount of laughter. When I was done, I gave it to Mr. Levine.

Who just loved it.

The Year of the Comet was my second original, a romantic thriller, about a chase for the world's greatest bottle of wine, and you can read all about it in the chapter with its name on it. I will add only this here--

--Mr. Levine loved it too.

I wrote the part of Blackbeard for Sean Connery, and Mr. Levine got the idea of casting the two James Bonds, having Roger Moore play the more elegant Bonnet. Another casting notion was the two Moores: Dudley (10 had happened) as Bonnet, Roger shifting over to Blackbeard.

In the wine movie, he wanted Robert Redford in the Cary Grant part.

Obviously, you did not see these movies.

What happened?

When Mr. Levine had come to me for A Bridge Too Far, he was pushing seventy, and he hated being out of the loop, was willing to take almost any gamble. Now that Bridge and Magic had helped restore him, his needs were lessened.

He was also older now.

But most critical: the price of movies had begun to skyrocket. So the fact that he was his own bank, so wonderful earlier, was now a huge problem--he was rich, but not that rich. Some research was done on the cost of constructing that everyday little item, the pirate ship.

You don't want to know.

Stars' salaries.

You don't want to know.

He had chances to lay the scripts off to studios but he couldn't do that, y'see, because then he'd be just like everybody else, taking shit from the executives. When he was the bank, he gave shit. I heard him blow studio heads out of the water. I saw him sit at his desk, smiling at me, while he hurled the most amazing insults at these Hollywood powers--

--and they had to take it--

--because he had movies they wanted.

That was the fucking staff of life for the old man. His ego would not allow him to be just like everybody else. He didn't need it.

So both scripts just lay there. (They very well may have been unusable scripts--always a very real possibility when I go to work--but that was not the governing principle here.) I never wrote the third original--Mr. Levine and I parted company.

I was O for two.

The Ski Bum began as an article in Esquire by Jean Vallely. Briefly, it concerned a ski instructor in Aspen who led a very glamorous life. Wealthy and famous clients, the kind of romantic existence most of us only moon about.

That's by day.

By night he was aging, broke, scraping along in a trailer with a wife and little kid.

I thought it would make a terrific movie.

The producer had bought the underlying rights. I signed on, went to Aspen, noodled around, did my research, went to work on the screenplay. Got it to the producer and the studio, Universal.

The producer loved it.

Alas, Universal's studio head hated it. When the producer left for another studio, he asked to buy it back, take it with him. Universal said, no conceivable way. We hate this piece of shit and we are going to keep it forever, thank you very much.

I always thought that was strange. If you hate something so much and you're offered a fair price to unload it, why keep it around? I did know, of course, the most usual reason--fear of humiliation. What if a studio gives up a piece of material that turns into Home Alone (happened) or E.T. (happened)?

But this was all company stuff, taking place far far above my head.

Dissolve, as they say (they really do), Out There.

It's a couple of years later and another executive has come to power at Universal. The guy who hated it so much is still above him, but this secondary power likes the screenplay and wants to see the movie made. We met and his first words to me were these: "You don't have the least idea what happened, do you?"

I didn't then.

I do now.

The producer had been, at the time, relatively new in the picture business. But he was a gigantic figure in the music business: Name a superstar singer, he handled him.

Well, Universal owned an amphitheater and needed talent to fill it. So the very great Lew Wasserman made a deal personally with the producer to handle the amphitheater and also have a movie-producing deal. Anything he wanted to make was an automatic "go."

With one teensy proviso: it had to cost less than an agreed-upon amount. Anything that cost more, Ned Tanen, the head of Universal Pictures, would have to agree to.

The Ski Bum, which needed stars and snow and all kinds of other expensive stuff, obviously needed Tanen's okay.

This presented kind of a problem for the picture because, decades ago, Tanen and my guy had been together in the mailroom at William Morris, where so many great careers were launched.

And they had hated each other with a growing passion since then.

Not only that, Tanen was pissed that the producer had gotten a movie deal at his company by going over his head to Wasserman.

So there it was.

Tanen, of course, rejected it. And, of course, rejected any attempt to buy the screenplay back.

The new executive and I tried an end run. Tanen never budged.

O for three.

The Right Stuff came next. A ghastly and depressing saga (recounted in magnificent detail in Adventures in the Screen Trade, so I won't repeat it here). I left the project angry and frustrated. These were bad times in America--the hostages had just been taken in Iran--so I had wanted to write a movie that might have a patriotic feel. The director wanted something else.

O for four.

On Wings of Eagles was not called that when I got involved. The famous Ken Follett book and the miniseries were still in the future.

But Ross Perot, who controlled the material, was interested in mak-ing a movie about the wonderful time when he masterminded breaking his employees out of an Iranian prison. I still had my patriotic need. I signed on.

The problem with this material was always very simple: it was an expensive action film but the star, the main guy, Perot's hero, "Bull" Simons, was not a young man. And Perot would never have betrayed the basic reality by allowing a younger man to do it.

There was only Eastwood. Had to be Eastwood. No one else but Eastwood. Dead in the water without Eastwood.

He took another military adventure movie, Firefox.

I was the one dead in the water now.

Until late in 1986, when the telephone rang . . .

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

?Aspirants and aficionados alike ought to be queuing up outside bookstores all over America to lay hands on Which Lie Did I Tell? It?s that good.??The Washington Post

Descriere

From the Oscar-winning screenwriter of "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" comes a garrulous new book that is as much a screenwriting how-to (and how-not-to) manual as it is a feast of insider information. Goldman, one of the most successful screenwriters in Hollywood today, tells all he knows. Devastatingly eye-opening and endlessly entertaining, "Which Lie Did I Tell?" is indispensable reading for anyone intrigued by the process of how a movie gets made.

Caracteristici

'The racy, readable memoirs of a man who has survived the vicissitudes of the most bizarre industry in the world with honours and riches' Barry Norman MAIL ON SUNDAY