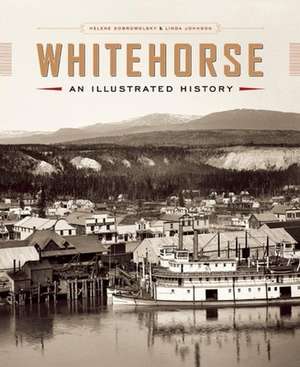

Whitehorse: An Illustrated History

Autor Helene Dobrowolsky, Linda Johnson Bob Cameronen Limba Engleză Hardback – 5 mai 2014

Whitehorse traces the storied past of Yukon’s capital city, from its origins in ancient aboriginal camps through the epic changes of the Klondike Gold Rush, the building of the Alaska Highway, and the settlement of First Nations land claims. Set amidst rolling mountains on the edge of the Yukon River’s swift green waters, the city today blends aboriginal traditions with the tastes, music, and cultures of people from around the world. Yukon authors Helene Dobrowolsky and Linda Johnson headed up a talented team of writers and researchers to create this portrait of a legendary place. From its early days, Whitehorse was Yukon’s transportation hub, linking the Pacific with trails, then rails, then the elegant sternwheelers that steamed downriver to Dawson City until highways and air travel took their place. The town hosted a dazzling parade of people over the centuries, many of whom appear in these pages: hunters, traders, gold-seekers, soldiers, miners, ships’ captains, entrepreneurs, dog-mushers, storytellers, sports icons, politicians, community builders, adventurers, and artists. Filled with lively writing, colorful anecdotes, and an impressive array of contemporary and archival photos, Whitehorse celebrates the history of a very special place.

Preț: 222.79 lei

Preț vechi: 277.10 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 334

Preț estimativ în valută:

42.63€ • 44.42$ • 35.30£

42.63€ • 44.42$ • 35.30£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780991858866

ISBN-10: 0991858867

Pagini: 364

Ilustrații: Color and B&W photos throughout

Dimensiuni: 231 x 279 x 30 mm

Greutate: 1.66 kg

Editura: Figure 1 Publishing

Locul publicării:Canada

ISBN-10: 0991858867

Pagini: 364

Ilustrații: Color and B&W photos throughout

Dimensiuni: 231 x 279 x 30 mm

Greutate: 1.66 kg

Editura: Figure 1 Publishing

Locul publicării:Canada

Notă biografică

Helene Dobrowolsky is a historian and an author based in Whitehorse, where she has operated a heritage consulting business with her partner, Rob Ingram, since 1988. Their many projects have included research, planning, writing, exhibit development, and interpretation. This is her sixth book. Linda Johnson moved to the Yukon from Ontario in 1974. She served as Yukon Territorial Archivist for 18 years and was a founding member of the Yukon Historical and Museums Association. Her publications include three books on northern history and cultures.

Extras

Introduction: Place of Many Stories

Raven soars high over the valley, sharp black eyes focused on the sights below as sunlight glows on clay cliffs, foaming plumes at the rapids and jade green waters in the canyon. Much has changed over the past century as a great inflow of people, buildings, roads, vehicles, farms, mines, dams and wires spread across the wilderness.

Raven remembers this land long before people came when it was covered by ice sheets in. The melting ice left an immense lake that filled the entire valley. When the lake left in a sudden rush, it carved into the rocks of the valley floor creating the bed for a new river thundering over boulders left by the ice. Grasses grew on the land, caribou returned and with them came people. People were here when fish returned to the river and nearby lakes. Early inhabitants survived volcanic ash drifting from the skies for months on end, floods changing the river’s course, summer forest fires, harsh winter winds and icy cold. They persevered by harvesting the land’s resources using skills passed on through countless generations.

Wolf walks silently through slender spruce trees to a bluff above the east riverbank. Glancing across the valley where the whine of jet engines mingles with birdsong, Wolf stands near a group of grave fences and howls. Wolf recalls hunting buffalo on grassy plains. As trees covered the hills, moose and elk moved into the area, and there were always caribou. A little over a hundred years ago, Wolf hunted in a pack near the big river but then the noise and lights of the new town drove away big animals. Now Wolf pauses briefly for a cautious stare as cars begin to roll across the bridge, signalling the start of another day in Whitehorse, the busy capital city of the Yukon. Creatures of instinct and mythology, Raven and Wolf have touched the lives and stories of people in this valley for thousands of years.

While geological features are plain to see, Whitehorse bears few signs of its ancient human occupations. People have been here since the end of the last ice age, living lightly on the land, building few structures and leaving few signs of their passing. The town’s oldest buildings are barely a century old, while earlier trails, campsites and stone quarries date back several millennia. The diversity of the past century is illustrated by gravesites memorializing family members of Southern Tutchone, Tagish Kwan, Tlingit, French Canadian, Scandinavian, English, Scottish, Japanese, German and many other linguistic and national origins. All are knit together by one common thread – lives formed and followed in this valley.

Chapter 3: Klondike Gold Rush, 1896-1898

Gold in the Klondike! Tons of gold, ready for the picking! This was the story that blared from countless headlines in July 1897, electrifying people all over the world, most of whom had never heard of the Yukon and Klondike rivers or even had a clear idea of their location.

Almost overnight, news of rich gold finds focused the world’s attention on a remote corner of Canada’s far northwest. Canadian history abounds in stories of the Klondike gold rush: the overnight millionaires; the speed with which the news spread worldwide triggering the world’s last great gold rush; the deluge of clerks, farmers, shopkeepers and experienced miners who risked all to make the trek north. Then there are the stories of the others who transported, safeguarded and occasionally fleeced the stampeders. For the aboriginal people who lived here, the stories are about family disruptions, the scars on the land left by the newcomers, game driven far from the river corridor, disease and, in some cases, new opportunities. For most, this saga is indelibly associated with Dawson City and the Klondike gold fields. In actuality, some of the most compelling stories of the rush took place near the Yukon River headwaters at the canyon and the rapids. More than any other factor, the stampede of gold seekers to the Klondike led to the founding of the town of Whitehorse.

Although prospectors had spent several years panning and sluicing in rivers and creeks of the upper Yukon River seeking the ultimate lode, the big strike was not made until August 17, 1896 and it involved several Tagish people from the southern Yukon. After marrying prospector George Carmack, Shaaw Tláa — better known as Kate Carmack — a woman from the Carcross area moved downriver with her non-native husband. Her sister had previously gone downriver with another white prospector. After two years, concerned family members travelled downriver to look for the two women. The party consisted of their brother Skookum Jim (Keish), his wife Mary and two nephews, Dawson Charlie (Káa Goox) and Patsy Henderson. After meeting up with Kate and George, the group hunted, fished and prospected. It was Skookum Jim, Dawson Charlie and George Carmack who staked the rich discovery claims on a feeder creek of the Klondike River. Rabbit Creek was quickly renamed Bonanza Creek and the three men became northern legends. The first rush to the area was by miners and prospectors in the Yukon River basin. Communities such as Forty Mile and Circle, Alaska were abandoned so quickly they became instant ghost towns.

It took nearly a year for the news to reach the outside world via two “treasure ships”. The arrival at coastal ports of the two steamships bearing early miners and their tons of gold generated an overwhelming response. The Excelsior docked in San Francisco on July 15, 1897 and the Portland reached Seattle two days later. The news swept throughout the world during a world-wide economic depression and captured the imaginations of thousands, inspired by prospects of instant riches. The rush was on as clerks, farmers, factory workers and merchants dropped everything to head north. It has been estimated that over 100,000 gold seekers set out for the Klondike while about 30,000 actually reached Dawson City.

There were many routes north but the most popular were the ancient trade and travel routes through the Coastal Range, over the White and Chilkoot passes to the great headwater lakes then down the Yukon River. Over the winter of 1897-98, the would-be miners packed tons of gear over the pass to the shores of Lindeman and Bennett lakes where they encountered a new challenge. They had to build watercraft to bear them down the Yukon River to Dawson City. The vessels were as varied as the carpentry and navigation skills of their builders. Soon after the ice went out in May 1898, a vast armada of rowboats, poling boats, dories, scows and rafts set off for the Yukon River. Many used tarpaulins as improvised sails to catch the prevailing winds on the headwater lakes and Lake Laberge. At one point, North-West Mounted Police officer Sam Steele counted over 800 vessels on an eight-mile stretch of Lake Bennett with many more on the way. He went on to note that while traveling 45 miles of the headwater lakes, none of the vessels were more than 200 yards apart.

After braving the windy headwater lakes, the travellers encountered the only major navigational hazard along Yukon River. Miles Canyon and the tumultuous rapids below were a bottleneck, slowing the great armada to a crawl. Rather than packing their gear around the five-mile portage, many inexperienced boaters dared the churning waters, risking the loss of gear, their vessels and even their lives. Generations later, Southern Tutchone elders told of an entire family—father, mother and children—who drowned in the rapids. Their ancestors had recovered the bodies and then buried them on the shore.

By June 1898, about 200 boats had been wrecked, 52 outfits of supplies had been lost and at least five men drowned. The death and destruction would undoubtedly have been much worse were it not for two factors: Norman Macaulay’s new enterprise, the Canyon and White Horse Rapids Tramway, and the intervention of the North-West Mounted Police.

The Tramlines and Canyon City

Norman Macaulay, a Victoria businessman, anticipated the needs of the northbound horde and came up with an ingenious way to capitalize on this perilous location. Over the winter of 1897-98, he hired a crew which included two brothers from New Brunswick, Tony and Mike Cyr, to cut and grade a right of way for a tramway on the east side of the river from the head of the Canyon to just below the foot of the rapids. The simple track, made of eight-inch diameter peeled logs set over cross pieces or “sleepers” carried horse-drawn tramcarts with concave cast iron wheels, capable of hauling large loads of freight and even small boats. To avoid the deadly rapids, customers paid three cents per pound of freight and twenty-five dollars for a small boat.

Within months, the ancient First Nations fish camp at the head of Miles Canyon was unrecognizable. By early summer of 1898, the site had been cleared and then filled up with a set of docks, a large log roadhouse, stables, several cabins, many wall tents and most critically the head of a tramline, hewn through the forest to the base of the rapids. The site was bustling with tons of freight being offloaded from ships. A windlass constructed in the spring of 1898, hauled up small boats that could be loaded onto the horse-drawn carts. Vessels were tied up all along the shore, everything from simple rafts to small sternwheelers.

Activity was everywhere. “Freight hustlers” unloaded tons of freight from the watercraft then repacked the boxes, sacks and gear onto the tramcars. Hostlers fed, groomed and harnessed the hard-working horses. Mounties rode along the line and monitored the flood of vessels to ensure safe passage. Anxious pack-laden gold seekers stumbled along the trail. Meanwhile thousands of boats crammed along the shoreline awaiting their turn to go through the Canyon.

Macaulay’s headquarters at the upriver end of the line became known as Canyon City. There he built docks and a large log roadhouse and bar. This was soon surrounded by smaller structures including crew quarters, stables and a North-West Mounted Police detachment. Another small settlement sprang up at the downriver terminus of the tramway. It became known as White Horse Landing, named after the nearby rapids. Although a few steamboats made the perilous passage through the canyon and rapids, none went back upriver and the humble community of White Horse Landing became the head of steam navigation on the Yukon River. Goods were transshipped between steamers on the upper lakes to sternwheelers that came upriver from the Klondike as far as Whitehorse.

By summer’s end, Norman Macaulay had lost his monopoly on the cartage business. Another Victoria businessman, John Hepburn, established “The Miles Canyon and Lewes River Tramway Company” on the opposite side of the river. The tramway began about one-half mile upriver from Canyon City and was about six and a half miles long. Hepburn’s track was built using rough-hewn four by six inch timbers, three feet apart with crosspieces set at five to twelve-foot intervals. Otherwise the operation was the same, carts with iron wheels, pulled by horses.

Hepburn’s tramway never attained the success of the original line across the river. Nonetheless, it was a hindrance to Macaulay and any expansion plans. After extended negotiations, Macaulay bought out the Hepburn tramway for $60,000. By the summer of 1899, Macaulay was planning to replace his horses and carts with a narrow gauge railroad. But even as Macaulay was prospering from his enterprise, a much more formidable competitor was building a railway north toward the Whitehorse Rapids.

North-West Mounted Police

The great northbound migration of thousands of would-be prospectors, most inexperienced in living on the land, was a potential recipe for chaos. This human swarm was also a magnet for opportunists who went along to “mine the miners”. While there was a respectable contingent of merchants, hoteliers and entertainers, there were also thieves, professional gamblers, confidence men and the infamous “macques” or pimps selling the services of prostitutes. The Alaskan port of Skagway was described as “little better than a hell on earth.” During the winter of 1897-98, robberies, public shoot-outs and even murders were common events.

Just across the international boundary, however, there was amazingly little crime. This was largely due to the presence of the North-West Mounted Police. The first detachment had traveled north in 1895 to establish a detachment at Forty Mile, scene of an earlier and smaller rush near the Alaskan border and approximately 50 miles downstream from the Klondike River. Consequently the Mounties were on hand for the great strike and their commander, Superintendent Charles Constantine was quick to call for reinforcements once he realized the extent of the influx of would-be miners. By early spring 1898, there were over 200* Mounties in the Yukon and a string of posts had been set up to shepherd the great flow of humanity from the mountain passes all the way to Dawson City.

In the fall of 1897, two Mounties had been dispatched to White Horse Rapids with six months’ worth of rations and orders to build a shack and assist winter travelers. The following May, Superintendent Steele sent two more men to Canyon City. Their orders were to warn stampeders of the hazards ahead and ensure “there was no overcrowding or unnecessary haste” in entering the canyon. By the time Steele inspected the site personally in June 1898, he found that the Mounties were spending most of their time rescuing unfortunates who had foundered in the rapids.

Steele immediately posted new orders for travelers to be enforced by the Mounties. He later reported on his actions:

When I went down the river, I found that accidents were of almost daily occurrence. This was in great measure occasioned by inexperienced men running boats through the Rapids and Cañon, in the capacity of pilot, many taking through women and even children. This I immediately stopped and gave orders that, in future, only really qualified “swift water” men were to be allowed to act as pilots. Since then no lives have been lost and only a small quantity of general goods.

After Superintendent Steele laid down his edicts, only experienced pilots were allowed to steer vessels through the canyon and rapids. Women and children had to walk around the rapids by the portage route. As Steele later put it, “If they strong enough to come to the Klondyke, they can walk the five miles of grassy bank to the foot of the White Horse.” Nonetheless, a few daring women disregarded the order to experience the thrill of the ride. Martha Louise Black, who later became a prominent Dawson resident and Canada’s second female member of parliament, insisted on riding through the rapids with her brothers.

Constable Dixon was charged with ensuring boats had sufficient free board, enabling them to safely ride the waves. The Mounties posted a list of qualified pilots to be selected in turn. The charges for piloting services were $150 for a steamer, $25 for a scow or barge, and $20 for a small boat. Pilots made up to ten trips a day through the canyon, then returned to Canyon City on horseback. For those unable to pay, Constable Dixon arranged for their vessels to be piloted free of charge.

Canyon City/White Horse Landing was one of the busiest detachments during the gold rush. Police checked all vessels to ensure they were not overloaded or carrying contraband liquor. The Mounties answered countless queries about the trip ahead and generally assisted travelers in many ways. By the end of the 1898 navigation season, over 7000 vessels had passed through Mile Canyon and the White Horse Rapids. After Steele’s edict, there were few accidents and no further lives were lost.

Raven soars high over the valley, sharp black eyes focused on the sights below as sunlight glows on clay cliffs, foaming plumes at the rapids and jade green waters in the canyon. Much has changed over the past century as a great inflow of people, buildings, roads, vehicles, farms, mines, dams and wires spread across the wilderness.

Raven remembers this land long before people came when it was covered by ice sheets in. The melting ice left an immense lake that filled the entire valley. When the lake left in a sudden rush, it carved into the rocks of the valley floor creating the bed for a new river thundering over boulders left by the ice. Grasses grew on the land, caribou returned and with them came people. People were here when fish returned to the river and nearby lakes. Early inhabitants survived volcanic ash drifting from the skies for months on end, floods changing the river’s course, summer forest fires, harsh winter winds and icy cold. They persevered by harvesting the land’s resources using skills passed on through countless generations.

Wolf walks silently through slender spruce trees to a bluff above the east riverbank. Glancing across the valley where the whine of jet engines mingles with birdsong, Wolf stands near a group of grave fences and howls. Wolf recalls hunting buffalo on grassy plains. As trees covered the hills, moose and elk moved into the area, and there were always caribou. A little over a hundred years ago, Wolf hunted in a pack near the big river but then the noise and lights of the new town drove away big animals. Now Wolf pauses briefly for a cautious stare as cars begin to roll across the bridge, signalling the start of another day in Whitehorse, the busy capital city of the Yukon. Creatures of instinct and mythology, Raven and Wolf have touched the lives and stories of people in this valley for thousands of years.

While geological features are plain to see, Whitehorse bears few signs of its ancient human occupations. People have been here since the end of the last ice age, living lightly on the land, building few structures and leaving few signs of their passing. The town’s oldest buildings are barely a century old, while earlier trails, campsites and stone quarries date back several millennia. The diversity of the past century is illustrated by gravesites memorializing family members of Southern Tutchone, Tagish Kwan, Tlingit, French Canadian, Scandinavian, English, Scottish, Japanese, German and many other linguistic and national origins. All are knit together by one common thread – lives formed and followed in this valley.

Chapter 3: Klondike Gold Rush, 1896-1898

Gold in the Klondike! Tons of gold, ready for the picking! This was the story that blared from countless headlines in July 1897, electrifying people all over the world, most of whom had never heard of the Yukon and Klondike rivers or even had a clear idea of their location.

Almost overnight, news of rich gold finds focused the world’s attention on a remote corner of Canada’s far northwest. Canadian history abounds in stories of the Klondike gold rush: the overnight millionaires; the speed with which the news spread worldwide triggering the world’s last great gold rush; the deluge of clerks, farmers, shopkeepers and experienced miners who risked all to make the trek north. Then there are the stories of the others who transported, safeguarded and occasionally fleeced the stampeders. For the aboriginal people who lived here, the stories are about family disruptions, the scars on the land left by the newcomers, game driven far from the river corridor, disease and, in some cases, new opportunities. For most, this saga is indelibly associated with Dawson City and the Klondike gold fields. In actuality, some of the most compelling stories of the rush took place near the Yukon River headwaters at the canyon and the rapids. More than any other factor, the stampede of gold seekers to the Klondike led to the founding of the town of Whitehorse.

Although prospectors had spent several years panning and sluicing in rivers and creeks of the upper Yukon River seeking the ultimate lode, the big strike was not made until August 17, 1896 and it involved several Tagish people from the southern Yukon. After marrying prospector George Carmack, Shaaw Tláa — better known as Kate Carmack — a woman from the Carcross area moved downriver with her non-native husband. Her sister had previously gone downriver with another white prospector. After two years, concerned family members travelled downriver to look for the two women. The party consisted of their brother Skookum Jim (Keish), his wife Mary and two nephews, Dawson Charlie (Káa Goox) and Patsy Henderson. After meeting up with Kate and George, the group hunted, fished and prospected. It was Skookum Jim, Dawson Charlie and George Carmack who staked the rich discovery claims on a feeder creek of the Klondike River. Rabbit Creek was quickly renamed Bonanza Creek and the three men became northern legends. The first rush to the area was by miners and prospectors in the Yukon River basin. Communities such as Forty Mile and Circle, Alaska were abandoned so quickly they became instant ghost towns.

It took nearly a year for the news to reach the outside world via two “treasure ships”. The arrival at coastal ports of the two steamships bearing early miners and their tons of gold generated an overwhelming response. The Excelsior docked in San Francisco on July 15, 1897 and the Portland reached Seattle two days later. The news swept throughout the world during a world-wide economic depression and captured the imaginations of thousands, inspired by prospects of instant riches. The rush was on as clerks, farmers, factory workers and merchants dropped everything to head north. It has been estimated that over 100,000 gold seekers set out for the Klondike while about 30,000 actually reached Dawson City.

There were many routes north but the most popular were the ancient trade and travel routes through the Coastal Range, over the White and Chilkoot passes to the great headwater lakes then down the Yukon River. Over the winter of 1897-98, the would-be miners packed tons of gear over the pass to the shores of Lindeman and Bennett lakes where they encountered a new challenge. They had to build watercraft to bear them down the Yukon River to Dawson City. The vessels were as varied as the carpentry and navigation skills of their builders. Soon after the ice went out in May 1898, a vast armada of rowboats, poling boats, dories, scows and rafts set off for the Yukon River. Many used tarpaulins as improvised sails to catch the prevailing winds on the headwater lakes and Lake Laberge. At one point, North-West Mounted Police officer Sam Steele counted over 800 vessels on an eight-mile stretch of Lake Bennett with many more on the way. He went on to note that while traveling 45 miles of the headwater lakes, none of the vessels were more than 200 yards apart.

After braving the windy headwater lakes, the travellers encountered the only major navigational hazard along Yukon River. Miles Canyon and the tumultuous rapids below were a bottleneck, slowing the great armada to a crawl. Rather than packing their gear around the five-mile portage, many inexperienced boaters dared the churning waters, risking the loss of gear, their vessels and even their lives. Generations later, Southern Tutchone elders told of an entire family—father, mother and children—who drowned in the rapids. Their ancestors had recovered the bodies and then buried them on the shore.

By June 1898, about 200 boats had been wrecked, 52 outfits of supplies had been lost and at least five men drowned. The death and destruction would undoubtedly have been much worse were it not for two factors: Norman Macaulay’s new enterprise, the Canyon and White Horse Rapids Tramway, and the intervention of the North-West Mounted Police.

The Tramlines and Canyon City

Norman Macaulay, a Victoria businessman, anticipated the needs of the northbound horde and came up with an ingenious way to capitalize on this perilous location. Over the winter of 1897-98, he hired a crew which included two brothers from New Brunswick, Tony and Mike Cyr, to cut and grade a right of way for a tramway on the east side of the river from the head of the Canyon to just below the foot of the rapids. The simple track, made of eight-inch diameter peeled logs set over cross pieces or “sleepers” carried horse-drawn tramcarts with concave cast iron wheels, capable of hauling large loads of freight and even small boats. To avoid the deadly rapids, customers paid three cents per pound of freight and twenty-five dollars for a small boat.

Within months, the ancient First Nations fish camp at the head of Miles Canyon was unrecognizable. By early summer of 1898, the site had been cleared and then filled up with a set of docks, a large log roadhouse, stables, several cabins, many wall tents and most critically the head of a tramline, hewn through the forest to the base of the rapids. The site was bustling with tons of freight being offloaded from ships. A windlass constructed in the spring of 1898, hauled up small boats that could be loaded onto the horse-drawn carts. Vessels were tied up all along the shore, everything from simple rafts to small sternwheelers.

Activity was everywhere. “Freight hustlers” unloaded tons of freight from the watercraft then repacked the boxes, sacks and gear onto the tramcars. Hostlers fed, groomed and harnessed the hard-working horses. Mounties rode along the line and monitored the flood of vessels to ensure safe passage. Anxious pack-laden gold seekers stumbled along the trail. Meanwhile thousands of boats crammed along the shoreline awaiting their turn to go through the Canyon.

Macaulay’s headquarters at the upriver end of the line became known as Canyon City. There he built docks and a large log roadhouse and bar. This was soon surrounded by smaller structures including crew quarters, stables and a North-West Mounted Police detachment. Another small settlement sprang up at the downriver terminus of the tramway. It became known as White Horse Landing, named after the nearby rapids. Although a few steamboats made the perilous passage through the canyon and rapids, none went back upriver and the humble community of White Horse Landing became the head of steam navigation on the Yukon River. Goods were transshipped between steamers on the upper lakes to sternwheelers that came upriver from the Klondike as far as Whitehorse.

By summer’s end, Norman Macaulay had lost his monopoly on the cartage business. Another Victoria businessman, John Hepburn, established “The Miles Canyon and Lewes River Tramway Company” on the opposite side of the river. The tramway began about one-half mile upriver from Canyon City and was about six and a half miles long. Hepburn’s track was built using rough-hewn four by six inch timbers, three feet apart with crosspieces set at five to twelve-foot intervals. Otherwise the operation was the same, carts with iron wheels, pulled by horses.

Hepburn’s tramway never attained the success of the original line across the river. Nonetheless, it was a hindrance to Macaulay and any expansion plans. After extended negotiations, Macaulay bought out the Hepburn tramway for $60,000. By the summer of 1899, Macaulay was planning to replace his horses and carts with a narrow gauge railroad. But even as Macaulay was prospering from his enterprise, a much more formidable competitor was building a railway north toward the Whitehorse Rapids.

North-West Mounted Police

The great northbound migration of thousands of would-be prospectors, most inexperienced in living on the land, was a potential recipe for chaos. This human swarm was also a magnet for opportunists who went along to “mine the miners”. While there was a respectable contingent of merchants, hoteliers and entertainers, there were also thieves, professional gamblers, confidence men and the infamous “macques” or pimps selling the services of prostitutes. The Alaskan port of Skagway was described as “little better than a hell on earth.” During the winter of 1897-98, robberies, public shoot-outs and even murders were common events.

Just across the international boundary, however, there was amazingly little crime. This was largely due to the presence of the North-West Mounted Police. The first detachment had traveled north in 1895 to establish a detachment at Forty Mile, scene of an earlier and smaller rush near the Alaskan border and approximately 50 miles downstream from the Klondike River. Consequently the Mounties were on hand for the great strike and their commander, Superintendent Charles Constantine was quick to call for reinforcements once he realized the extent of the influx of would-be miners. By early spring 1898, there were over 200* Mounties in the Yukon and a string of posts had been set up to shepherd the great flow of humanity from the mountain passes all the way to Dawson City.

In the fall of 1897, two Mounties had been dispatched to White Horse Rapids with six months’ worth of rations and orders to build a shack and assist winter travelers. The following May, Superintendent Steele sent two more men to Canyon City. Their orders were to warn stampeders of the hazards ahead and ensure “there was no overcrowding or unnecessary haste” in entering the canyon. By the time Steele inspected the site personally in June 1898, he found that the Mounties were spending most of their time rescuing unfortunates who had foundered in the rapids.

Steele immediately posted new orders for travelers to be enforced by the Mounties. He later reported on his actions:

When I went down the river, I found that accidents were of almost daily occurrence. This was in great measure occasioned by inexperienced men running boats through the Rapids and Cañon, in the capacity of pilot, many taking through women and even children. This I immediately stopped and gave orders that, in future, only really qualified “swift water” men were to be allowed to act as pilots. Since then no lives have been lost and only a small quantity of general goods.

After Superintendent Steele laid down his edicts, only experienced pilots were allowed to steer vessels through the canyon and rapids. Women and children had to walk around the rapids by the portage route. As Steele later put it, “If they strong enough to come to the Klondyke, they can walk the five miles of grassy bank to the foot of the White Horse.” Nonetheless, a few daring women disregarded the order to experience the thrill of the ride. Martha Louise Black, who later became a prominent Dawson resident and Canada’s second female member of parliament, insisted on riding through the rapids with her brothers.

Constable Dixon was charged with ensuring boats had sufficient free board, enabling them to safely ride the waves. The Mounties posted a list of qualified pilots to be selected in turn. The charges for piloting services were $150 for a steamer, $25 for a scow or barge, and $20 for a small boat. Pilots made up to ten trips a day through the canyon, then returned to Canyon City on horseback. For those unable to pay, Constable Dixon arranged for their vessels to be piloted free of charge.

Canyon City/White Horse Landing was one of the busiest detachments during the gold rush. Police checked all vessels to ensure they were not overloaded or carrying contraband liquor. The Mounties answered countless queries about the trip ahead and generally assisted travelers in many ways. By the end of the 1898 navigation season, over 7000 vessels had passed through Mile Canyon and the White Horse Rapids. After Steele’s edict, there were few accidents and no further lives were lost.