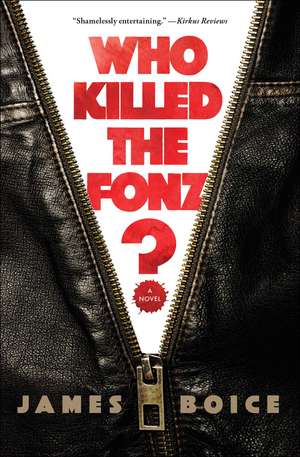

Who Killed the Fonz?

Autor James Boiceen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 mar 2020

Late October, 1984. Prince and Bruce are dominating FM radio. Ron and Nancy are headed back to the White House. And Richard Cunningham? Well, Richard Cunningham is having a really bad Sunday.

First, there’s the meeting with his agent. A decade ago, the forty-something Cunningham was one of Hollywood’s hottest screenwriters. But now Tinseltown is no longer interested in his artsy, introspective scripts. They want Terminator cyborgs and exploding Stay Puft Marshmallow men. Then later that same day Richard gets a phone call with even worse news: His best friend from childhood back in Milwaukee is dead. Arthur Fonzarelli. The Fonz. He lost control of his motorcycle while crossing a bridge and plummeted into the water below. Two days of searching and still no body, no trace of his trademark leather jacket, and Richard suspects murder. With the help of his old pals Ralph Malph and Potsie Weber, he sets out to catch the killer.

“Readers yearning for simpler times will enjoy this trip down memory lane, which is as comforting as an episode of Happy Days” (Publishers Weekly). Who Killed the Fonz? imagines what happened to the characters of the legendary TV show Happy Days twenty years after the series left off. And while much has changed in the interim—goodbye drive-in movie theaters, hello VCRs—the story centers around the same timeless themes as the show: The meaning of family. The significance of friendship. The importance of community.

“Wildly inventive and entertaining” (Booklist), Who Killed the Fonz? is an “irresistible” (New York Newsday) twist on a beloved classic that proves sometimes you can go home again.

TM & © 2018 CBS Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved

Preț: 85.17 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 128

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.30€ • 17.05$ • 13.54£

16.30€ • 17.05$ • 13.54£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501196898

ISBN-10: 1501196898

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1501196898

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

James Boice was born in California in 1982, raised in northern Virginia, and currently lives near Boston. He is the author of MVP and Who Killed The Fonz?

Extras

Who Killed the Fonz?

NOTHING WAS MOVING ON THE 405. Richard sat at the wheel, scanning the Corvette’s radio dial, looking for some kind of news about the jam, but there was nothing. He looked at the clock again. Couldn’t be late. On the radio was Prince. It was his daughter’s favorite. He himself wasn’t sure about all that innuendo and raunch. He wasn’t sure about much these days. He had seen the film that Prince had starred in and had liked it more than he thought he would. He had expected a two-hour music video, but it was a drama about family and love and what it meant to pursue your dreams—what it cost. His friend Steven had made him watch it. Called him over to his private theater in his house. It had been nice of Steven to call. It had been months. Maybe longer. At one point he asked Richard what he had been working on. All he had to do was tell him about his project. Steven would have helped him. All he had to do was say the words. But Richard couldn’t tell him. He muttered that he was tinkering with a few different things, then changed the subject to the new project Steven was executive producing, a time-travel film with the kid from Family Ties.

He and Steven had started out around the same time. They were part of a crew of hustlers, strivers, doing whatever they could to make films—Spielberg, Scorsese, Lucas, Cunningham. Back then they all thought it would be Richard who would be the one inviting them over to his private movie theater one day. He had been the first to sell a script, first to get an Oscar nomination. Now almost all of them had become directors on a first-name basis with the world, and he was just another no-name chump stuck in traffic on the 405, running late to lunch with his agent, who held the fate of his project in his hands.

• • •

HE STEERED THE CORVETTE DOWN sunset. The clock said he was okay on time. He relaxed, his mind wandering. He wondered yet again whether or not his agent wanting to meet on a Sunday meant good news. Lori Beth and his mother warned him not to get his hopes up. He could not help it. If the news was bad, legendary Hollywood agent Gleb Cooper would not waste his time with a face-to-face. Especially not on a Sunday. Richard had a good feeling. This would be the day he had been waiting three years for.

He passed Book Soup, where it had all started.

He had been browsing the bargain bins when he came across a remaindered copy of a bizarre-looking novel. Black dust jacket, no art—just the title and author’s name in big, elaborate font that seemed taken off the side of a nineteenth-century circus wagon. It was the black-and-white author photo that most intrigued Richard. Most of them posed very self-seriously, bloodless Ivy Leaguers in tweed. This one, however, named Cormac McCarthy, wore jeans, denim jacket, had uncombed hair. The look on his face was surprised, like someone had shouted his name and snapped his photo when he turned around. He looked like he couldn’t figure out what he was doing on the back of a book jacket. In the background there was not a prestigious college campus or the slick Manhattan skyline but an industrial town. Smokestacks, a bridge, a shipping channel. It looked like the same kind of town Richard had come from.

He took the book to the register. The clerk gave him an approving nod. A good sign. That night at home he started reading.

He could not stop. Three days later, he was still reading. He would have finished the book sooner but the language was like nothing he had ever seen outside of Shakespeare. It was almost something physical to grapple with. He kept having to put the book down and reach for the dictionary. Concatenate. Leptosome. Electuary. They were not even words—they were portals to new worlds.

The story’s grip on Richard was just as mysterious. A man lived on a houseboat in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the 1950s. He seemed to have come from a prestigious family but had been somehow alienated or cast out. A sordid cast of fringe-dwelling characters wandered in and out of his life, pulling him into their small-time hustles and drunken misadventures. Not much happened, on the outside. But on the inside, in the heart and mind of this man, named Suttree, as he tried to hold on to his sense of self in an ever-changing world bent on taking it from him, everything was happening. Everything. Richard understood right away that he knew this character. Felt like he had known him all his life. He could not say why. Not since he was a teenager had he felt this way about a book. Something about this novel brought him back to that vulnerable, openhearted place he had been when he was young. And he wanted desperately to hold on to it. Richard did not know why this character was so appealing to him. Because with Richard’s sports car and slick suits and Spanish Colonial in Sherman Oaks with a pool and detached mother-in-law bungalow in back, he and Suttree would not seem to have a lot in common. He certainly wasn’t a drinker like Suttree. In fact, he rarely drank. Not since one night long ago when he was a young father and the pressure got to him—he took it too far that night and never made that mistake again. But that was what made the book so powerful. It was a kind of art he had never encountered before: the kind that would seem to have nothing to do with you yet still gets to you in ways art that has everything to do with you does not.

When he closed Suttree after the final page, he saw the whole thing in his head, the film adaption he would make of this novel. He saw it from the opening theme through the end credits. I am going to make it, he told himself. He looked at the cover, then the author photo. He felt a warmth growing in his chest. His fingers and hands filling with blood, like they had been asleep but were now waking up. I am. He had to make this film. He was going to write it, and he was going to direct it. It would be his directorial debut.

Not only that—it would be his triumphant return from the brink of extinction.

• • •

IT WAS A STRANGE CHOICE of restaurant. Typically his meetings with Gleb Cooper took place at Musso & Frank, where Gleb had a booth they’d clear out for him upon his arrival, and the maître d’ would accommodate his every need. Once Gleb had ordered catfish. The menu did not include catfish. But Gleb wanted catfish, and Gleb got catfish. Richard could not imagine how they located and prepared one so quickly, but it arrived on time with Richard’s steak tartare. Richard would try to discreetly eyeball the luminaries filling the surrounding tables without Gleb noticing, because if he caught his companion’s gaze wandering like that, he took it as an insult, a challenge, and he would not let it go. He would hold on to it for the rest of the meal. And he would mention it at every meal after. But Richard would tell his grandchildren about that day at Musso’s when Warren Beatty came over to their table to shake Richard’s hand because, Warren Beatty said, he had just heard from a friend at the Academy that Welcome to Henderson County was going to be nominated for an Oscar, and he wanted to shake the hand of the man who had written it.

But this place. It was no Musso’s. It was a forgettable Italian spot on Wilshire called Michelangelo’s. Richard had never heard of it. There wasn’t even a valet. Inside there was no Warren Beatty, nor anybody else, aside from some waiters, a bartender leaning over the want ads of the Sunday Los Angeles Times, and Gleb Cooper in a booth.

He almost did not recognize him, because it was the first time he had ever seen him not wearing a suit. He almost did not even see him at all. He had chosen a booth in the corner, in the shadows. He had his head down, reading the paper, a golf hat pulled low. How old was Gleb? Richard could only guess. He had been a ubiquitous presence in Hollywood longer than anyone could remember. But he still maintained the vitality and power of a man Richard’s age. He always wore custom suits. He was the one who first encouraged Richard to put more effort and consideration into what he wore. “Dressing well is a way of showing respect,” he’d say, “not just for yourself but for everyone else. Give respect, get respect. That’s how it all works. Thar’s all you need to know.” When Richard first came to town twenty years earlier, he wore the one blazer he had, which was ill fitting and badly cut. He had gotten it off the clearance rack at Gimbels back home, and he wore it until the buttons fell off and his elbows just about poked through. He thought he looked sharp, but looking back on it he probably looked like an overgrown prep schooler. When it wasn’t that blazer, it was pastel cardigans—Kmart or Gimbels, whichever was cheaper. Gleb told him he looked like Mr. Rogers. Richard thought it was a compliment, because Mr. Rogers was a good person with a solid character, but it was not. Gleb brought him to the store on Rodeo where he bought his suits, put down a stack of money, and instructed the serious quiet man to take care of his boy. He did. Richard still bought his suits there. Every few years he had them altered to match the changing fashions. Today he was wearing the pale gray double-breasted Calvin Klein. It was Lori Beth’s favorite.

Gleb was dressed for the golf course. Richard could not tell if he was on his way to the links or on his way back from them. It seemed to be an important difference. For the first time, Gleb looked to Richard like an old man, shriveled and small, bent as he was with the paper up close to his face, squinting to read it. Richard grew nervous. But then Gleb looked up and noticed him and his voice came booming across the room with the same energy and enthusiasm as always.

“There he is!” Gleb shouted across the empty restaurant. “There he is! Get over here! Sit, sit!”

Richard went over and slid into the booth. Gleb was drinking coffee. The waiter poured Richard a cup.

“Thanks for meeting me on a Sunday,” Gleb said. “I couldn’t wait to talk to you. I was too excited. Are you coming from church or something? What’s with the suit? You’re making me feel like a schlub.”

“Now you know how the rest of us usually feel,” Richard said.

Gleb grinned. He smoothed his yellow polo shirt, glancing down at it. “On my way to play some golf.”

“No kidding.”

“Sunday’s golf day. No one is allowed to bother me on golf day. I’ve turned down meetings with God on Sunday. No meetings on golf day. That’s my rule. You need rules for yourself. Remember that. Write that down.”

A good sign. A great sign. Richard’s heart was beating hard. It had to be good news. He fought to control the grin on his face. It was a struggle he had been up against since he had arrived in town. His midwestern grin was its own animal—if he did not take care, the thing would eat his entire head. And in this town, a goofy grin like his was a sign of weakness. If you were going to smile, it had to be cool and confident, like Jack Nicholson’s, not unabashed and eager like Richard’s.

Stay cool, Richard told himself. You can celebrate when you get home.

“I’m flattered,” Richard said.

Gleb shrugged. “I’m excited to talk to you. I couldn’t wait.”

“I’m excited too, Gleb. I can’t tell you how happy I am that you see what I see in this project. I know I’ve sort of been on the sidelines the last few years, but—”

“Sort of? Richard, you wouldn’t be more on the sidelines if you were Broadway Joe Namath wearing a Los Angeles Rams jersey in 1977.” Gleb laughed at his own joke.

“Got me,” Richard said, holding his hands up. “Guilty as charged. It’s just that I’ve wanted to get this project right, you know? I’ve wanted to take my time with it, make it perfect, and it’s been very difficult, it’s very dense material, very personal and rich, and, boy, the stream of consciousness of the prose will be very challenging to portray on-screen, but I’m up for it, I really am, I know exactly how to do it.” He started to go into the technical approach he intended to take but cut himself short, seeing Gleb’s eyes glaze over. “Anyway, I want to thank you for sticking with me and believing in me like you have. I cannot wait to get started.”

Gleb said, “Now hold on, Richard, let’s back up. What the hell are you talking about?”

“Suttree,” Richard said, panic creeping in quietly. “We’re here to talk about Suttree, right?”

Gleb let out a deep, wheezing sigh. “Okay,” he said. He waved the waiter over. “Two gin martinis,” he said. “Bone dry and dirty.” The waiter nodded and left.

Richard understood now, all too well. This is why Gleb wanted to meet at such an empty, out-of-the-way restaurant. It wasn’t that he was embarrassed to bring washed-up talent around to his usual haunt. Though that was clearly part of it. No, it was also out of mercy. Gleb had called this meeting planning to kill Richard’s dream but had wanted to spare him the additional pain and suffering of doing it in front of his professional peers, such as they were. He was planning cold-blooded murder en route to a late tee time and didn’t want any witnesses.

“Of course a hit job like this would take place in an Italian restaurant,” Richard said. Gleb did not seem to hear.

“Look, here it is. Okay? I’ve met with everyone about your project. Everyone. From Warner Brothers to a guy named Warner who finances low-budget monster movies for the tax write-off. There is no interest. Zero. I encourage you strongly to forget Suttree. Move on. This should help you do that: I got something for you. That’s why I wanted to meet today. I have a job for you, Richard.”

“If it’s writing a Sorority Slaughterhouse sequel, forget it.”

Richard had written the schlocky slasher film years ago, when he was first starting out. It was the first job Gleb got him. Everyone was doing the same thing, all his friends. Whatever it took. But unlike their films, which were quickly forgotten except among film scholars as their creators ascended to greater things, Sorority Slaughterhouse had become a cult hit. For a time it had been a favorite of midnight screenings. Theater owners used to beg for a sequel. Gleb had pressed Richard on it a few times, but Richard had always refused—especially after the Oscar nomination.

“That was a very profitable picture,” Gleb was saying, pointing his finger at him. “Don’t turn your nose up at it. Be proud of it. You were hungry. You were driven. You were willing to do whatever you had to do. You had grit.”

“What do you mean had? I still do.”

“Sure, sure, yeah, you still do.” Richard could tell Gleb was saying it but he wasn’t meaning it. “But anyway, Richard, no, it’s not that, it’s not Sorority Slaughterhouse.” He moved his eyes to a point just behind Richard’s left shoulder. His face took on an expression of amazement. He raised his hands in the shape of a camera frame, like a cinematographer gauging a shot. Gleb held it there for so long that Richard turned his head to see if something really was back there. Then Gleb announced majestically, jolting his hands at both words for emphasis: “Space Battles.” He moved his hands a little lower then jolted them again as he said, “Original Screenplay by Richard Cunningham.”

Richard sat forward, his grin coming to life again. He knew George, they used to shoot pool together—why hadn’t George called to break the news himself? He didn’t know he was planning another Star Wars. And he certainly had no idea he was thinking of Richard to write it.

“Gleb, that’s incredible news. Incredible! Star Wars! Wow! I have ideas already. I thought the last installment lacked the gravitas of the original. Man, I’d love to restore some of the seriousness and literary value to the franchise.” He let out a whoop that turned the heads of the staff. “Wow, Gleb. I could kiss you. This is exactly what I needed. It’s going to change everything for me.”

“What? No, Richard, no, not Star Wars. Space Battles.”

“I don’t understand.”

“A wicked kingdom, an underdog hero, a foxy princess—and all of it in space.”

“That sounds an awful lot like Star Wars, Gleb.”

“No. Space Battles has two things Star Wars does not.”

“What’s that?”

“Blood and bazoongas.” Richard put his hand over his face. Gleb continued. “Did Star Wars have blood and bazoongas? No it did not. Think about how much more money it would have made if it had. It’s more realistic. It’s realism. That’s your trip, right, Richard?”

The waiter set down the martinis and a small dish of olives. Gleb speared one and put it between his molars and bit. He lifted one of the martinis and drank. “Drink up,” he said, gesturing to the other martini. “Relax. Celebrate. We’re celebrating.”

“No thank you,” Richard said. He and Gleb had worked together fifteen years, and Richard had never been a drinker. Now he was starting to wonder how well his agent knew him. He wondered if Gleb had even read his Suttree script.

Gleb reached over and slid the drink like a chess piece to his own side of the table.

“I don’t want to do this. I want to make Suttree,” Richard told him.

“I know you do. But, look, Richard, the days of a movie like that getting made are over. Ten years ago, yeah, maybe. But now? People just don’t want it. They want people running for their lives and heroes saving the day. They want the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man exploding over Manhattan. They want Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone mowing people down. The rest of your generation figured this out long ago. Look at your buddies. Look at Spielberg. Why can’t you be more like him? Why can’t you just give the people what they want? Now, this job, this is your chance to do that. The kid producing Space Battles, his daddy’s a shah or a sultan or something, I don’t know what he is, but the kid’s a prince. A real live prince. He’s got jets. He’s got jewels. He’s got it all. And he wants to get into pictures, Richard. I know this sounds awful to a writer of your caliber, but know what it sounds like to me? Work. A job. Something you’re sorely in need of.”

Gleb was not wrong. Three years Richard had spent on Suttree. His bank account was low. He and Pepperdine University were square through the rest of 1984, but next year he was not sure where Caroline’s tuition money would come from. And there were still the mortgage payments. The city had just bumped up their property taxes. Downsizing was not an option. Not with Marion.

“How much does it pay?” Richard said, looking down at the table, at his hands gripping his thighs.

“Two hundred,” Gleb said. “Plus five percent on first-dollar gross.”

Richard took a deep breath. “That’s good money.”

“It’s very good money.”

It made Richard think.

“What if I wanted to make my movie myself? How much would it cost?”

Gleb laughed and raised his glass to his lips.

“No, I’m serious. How much?”

“Come on, Richard. What you want to do, you’d have to do it on location. You’d have to fly all the actors and crew out to Tennessee or somewhere that can pass for it. That’s expensive.”

“So you did read my script.”

“Of course I did. And I’ll be honest. I didn’t get it. Neither did anyone else. Also you’d need to hire a director of photography who can figure out how to shoot on a rocking, swaying boat. You’d need to hire a director.”

“No, that’s me, I’ll be the director.”

“No, no investor would go for it. You don’t have the experience. All told, you’d need five million. At least. You’re talking about a major uphill climb. Major. I just don’t have the time to help you with that. Richard, I’m sorry, but that project is finished. Listen to me: I know what I’m talking about. Take this job. Take Space Battles. Knock it out in a few weeks, cash your check, and we’ll figure out the next thing. You really have an interest in directing? I’ll talk to the prince, see if I can get you a PA position or something. Start getting some experience on set.”

Richard glanced around the restaurant. “Funny,” he said, “it’s not at all like I imagined.”

“What’s not?”

“Rock bottom.”

Gleb sighed and said, “It’s not rock bottom. It’s life. Right now this garbage is all I can get for you. This is it. This is where you are. It’s Space Battles or nothing.”

“Can I think about it?”

“Of course. Take a few days. But I need an answer by Saturday. The prince is leaving the country in two weeks, and we need to set up meetings before he goes. And, Richard, when I say it’s Space Battles or nothing, I mean it. If your answer is no, I’m sorry, but there’s nothing more I can do for you. If you want to continue in this business, you’ll have to do it without me.”

• • •

AS HE DROVE HOME HE kept thinking about what Gleb had said about his friends, the filmmakers he had come up with, many of whom were not only successful writers and not only A-list directors but also serious, big-time producers as well. What Gleb had said was true. The successful ones were the ones who had accommodated the sensibilities of the mainstream. They had not been rigid about their aesthetics. They had found a way to do what they wanted to do while appealing to the masses. They had leveraged their commercial work to facilitate their personal work. Maybe that was the way. One for them, then one for you. What was it that kept Richard from just doing that? Why couldn’t he just play the game?

That’s what it was to people in the industry now, to people like Gleb—a game. A zero-sum one. They read Variety for the latest box office figures the way stockbrokers picked apart the Nasdaq reports, the way gamblers chewed up the sports pages looking for any edge. Box office, box scores—they were the same thing to these people. It was not about stories, or film. It was about winners and losers. Nothing in between. He wasn’t naïve. Movies cost money. A lot of money. Production, distribution, marketing. None of it was cheap. And the people who put up the money weren’t doing it out of benevolence. They expected their investment back and then some. He understood all that. But when it came down to it, he still saw cinema as art, not business. If his goal was making money and working with people only interested in the same, he would have become an investment banker.

And then he would have become a patient in a psych ward.

His more successful friends were drawn to the material they did. They weren’t faking it. They had to do their movies the way he had to do Suttree. The question was why did he have to do Suttree? It was a question he could not answer. The enigma of the creative process, he supposed. Even if he could answer it, he would not want to.

But maybe he was naïve. Maybe the reality of making movies was that you had to do what you did not want to do, and he just needed to accept it. Maybe he was still too much of that earnest midwestern kid he once was. Too sincere. Couldn’t lie. Couldn’t fake it. Couldn’t blow smoke. Didn’t smoke. Too clean for this smutty town. Being married to his high school sweetheart didn’t help with this veneer of edgelessness that made him just about disappear. Still madly in love after almost thirty years. Once he went to the Playboy mansion with his friend Brian De Palma, whose latest directorial effort just last weekend opened at $23 million (but who was counting?). It was not Richard’s scene. He’d spent the whole party hiding out alone in Hefner’s library, reading his first edition The Great Gatsby. Now that was Richard’s idea of a good time. With charisma like that, maybe it was no wonder he was overlooked.

Then there was the fact that he still lived with his mother.

It had not been planned. After his father passed, Marion decided to just stay out here. She and Howard had been talking about moving to Los Angeles anyway. The weather was nicer, the pace was more mellow, and it would put them closer to their grandkids. It would be better for Howard’s heart.

The cardiologist had told them not to make that trip. There was an appointment coming up. A very important appointment. It would give them a better idea of what was wrong this time. Richard begged his father to listen to the doctor. And he could not get them into the ceremony anyway—they would have to watch on TV from Richard and Lori Beth’s house. “But what if you win?” Howard kept saying. Richard told him he wouldn’t win, there was no chance, not up against Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. But Howard would not listen. “Think it’s every day my son gets nominated for an Oscar?” He was going to be there in person, no matter what. Richard never for a moment thought he would win, but he was still disappointed when it was not his name they called. Coming home with Lori Beth that night and having his parents there, seeing how proud they were of him, supporting him the way they always had when he was a kid—he was glad they had come. He was relieved.

They all stayed up late that night, Howard telling Richard his favorite parts of Welcome to Henderson County. It had not played in Milwaukee. They’d had to drive two and a half hours in the snow to see it in Chicago. When it ended, they rose from their seats and gave it a standing ovation.

“After the show,” said Marion, “your father stood outside the theater door, shaking everyone’s hands and thanking them for coming, and telling them the writer was his son. He even started signing autographs.”

Howard shrugged. “They asked me for them.”

Before they all turned in that night, Howard stopped Richard at the foot of the stairs. He took his son’s face in his hands. “I owned a hardware store,” he said.

Richard was confused. “Yeah, Dad,” he said. “I know that.”

“A hardware store. Nails. Wood.” Richard did not say anything. Howard’s eyes were glistening, turning red. Richard just looked back into them. “And my son’s an artist. A hardware store and my son’s an artist.” Richard was an inch taller than his father. Howard pulled his head down and kissed him on top of it. “My son’s an artist.”

They were supposed to fly back in the morning. Howard did not come downstairs. Marion kept calling up to him, “We’re going to miss our flight!” Finally she went up. Down in the kitchen, Richard and Lori Beth heard her saying his name. Over and over she said it. Soon she was yelling it. Yelling for them.

They buried Howard in Los Angeles. To keep him near his beloved grandkids. Marion took over the empty in-law suite out back by the pool and gave the house in Milwaukee to Joanie and her husband, Chachi.

“My son’s an artist.” Richard never forgot it. Maybe those words were why he could not bring himself to play the game, to bend and concede.

Richard was lost in these thoughts. He did not see the red light until it was almost too late. He slammed the brakes to avoid making roadkill out of two young women crossing the street. The redhead slammed her palms onto the Corvette’s hood.

“Hey man!” she shouted. But it wasn’t a she at all. “Get out of the car!” the man was saying.

“Be cool, Axl,” said the other one, also a man, who wore a top hat. He pulled Axl away, and they crossed the street. Richard watched them walk off, stapling flyers to every telephone pole they passed, advertisements for their band. He remembered when he used to have that faith and conviction about what he was doing. That grit. He even used to have that red hair. All of it had faded these years under the Southern California sun.

Enjoy it while it lasts, he said to himself.

Then the light turned green and he headed home, to deliver the bad news to Lori Beth and his mother.

• • •

AFTER MORE THAN A DECADE in Los Angeles, Marion Cunningham had developed a passion for crystals, star charts, and yoga. She had stopped cutting and coloring her hair after her friends at the holistic health spa had told her that it was where her life force was stored and that toxins from the chemicals in hair dye could seep into the scalp and blood. They tried to convince her about reincarnation, but she couldn’t be sold, though she did believe it was a beautiful concept she wished was true. Mostly she was fanatical about her macrobiotic vegetarian diet—she was not allowed to cook for Richard and Lori Beth because they couldn’t stand all that tofu and raw alfalfa—but when her grandkids were home she would cook anything they wanted, even meat. It was fine with Richard that she had become so earthly and nonmaterialistic. In her former life as a Milwaukee homemaker, when her days were spent chopping food and sweeping floors and carrying around children and propping herself up, she had taught herself to live without wanting more.

But walking into the house in Sherman Oaks, he was in no mood to receive a lecture on how Mercury being in retrograde had caused the meeting with Gleb to go badly. She and Lori Beth had both warned him not to get his hopes up. He had told them they were wrong. The fact that they were right made it all worse. When he found them in the high-ceilinged living room, sitting on the facing couches in grim silence, he wanted to be anywhere but where he was.

“You were right,” he said. “Okay? Suttree is done. I was insane for thinking it would ever happen. Of course no one wants a movie like that. And I really believed they might let me direct it? Three years of my life—gone.”

Saying it out loud made him dizzy.

“Oh, Richard,” Lori Beth said, looking at him with pity. It was the last thing he needed.

“Sit down, honey,” Marion said. She had been crying. It made him realize that Lori Beth had been too. They knew he would be coming home with bad news, he thought. They knew he was going to be destroyed at that meeting, and they let him go into it anyway, they didn’t try to shake him out of his delusion.

He turned away from them. “No,” he said. He started walking out of the living room. “I need to take a walk or something.”

“Richard,” Marion said, “sit down.” It had been years since he had heard such assertiveness in her voice. He came back and sat in an armchair.

“Look,” he said, “I appreciate your sympathy. I really do. But—”

“Joanie called,” Marion said.

“From Tahiti?” Richard said. His sister and Chachi were there for their tenth wedding anniversary. “Why? Is everything okay?”

Marion cleared her throat and looked at Lori Beth who said, “She was calling about Fonzie.”

It took him a moment. The context was too displaced. It was not the name of a producer or an actor or a director or a studio executive. So it did not seem to be the name of anyone. “Fonzie,” he said.

Lori Beth breathed deeply and tried to explain. “Last Thursday night, he was driving across Hoan Bridge and . . .” She could not finish.

“And what?” She just shook her head no. She put her hand over her eyes.

“Richard,” Marion said. “He was in an accident.”

“What happened?”

“Joanie didn’t know all the details. She only knew what Al told Chachi when he called to tell them: he lost control of his motorcycle and crashed into the guardrail. He went flying over the handlebars, over the guardrail, and down into the lake. They’ve been looking, but they haven’t found it.”

“What do you mean it?”

“The body, Richard,” Marion said quietly, sweetly. “His body.”

Richard was shaking his head side to side, unable to stop. He moved to the edge of his chair, stood up, then sat back down. Lori Beth reached over and put her hand on his. She looked at him with crying eyes.

“I’m sorry,” she was saying.

There was a mirror on the wall. Richard could see himself all too clearly in it. Red eyes. Crow’s feet. Steadily receding hairline. Inexplicable wobble of flesh beneath his chin—the beginnings of an old man’s neck. Each man has that moment in his life when he looks in a mirror and sees for the first time the uninteresting old man young women see when they look at him—if they look at him, which, because he’s an old man, they do not. This was that moment for Richard Cunningham. Not the day he moved Richie Jr. into his first apartment, and not the day he dropped Caroline off at college. This day. The day he realized middle age had met him like a two-by-four to the face.

The day he learned his best friend from childhood was dead.

• • •

MARION AND LORI BETH LEFT him sitting there in the living room to give him some time alone. He was still there two hours later when Marion returned to check on him. She stood beside him. “You should eat.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“I’ll make you something. No tofu, I promise.”

“No thanks, Mom.”

She sat on one of the sofas.

“Remember all the things I did just to make a living?” he said. “Lori Beth’s and my first few years out here trying to make it?”

“I remember when you were selling watches over the telephone from one of those seedy call centers in Encino, was it?”

“And that was the best one. And all the apartments Lori Beth and I lived in. All those dumps. Mice. Busted plumbing. The police asking about our neighbors.”

“I used to worry about you.”

“We were fine. It was never dangerous.”

“I wasn’t worried about your safety, I was worried about whether you were happy.”

“I was. Those were some of the best days of my life. We went through times that were so uncertain and so terrifying and made us ask ourselves every day if we should call it quits and just go back home and get more practical jobs, play it safe. But whenever I thought about quitting, you know what I thought about to keep myself going? I thought of Arthur Fonzarelli. I imagined what he would say if I went back to Milwaukee and told him I had quit. I pictured the look in his eyes. How disappointed he would be in me if I ever told him I had stopped believing in myself. He wouldn’t have said anything. He would have just looked at me a certain way. I can almost see it now. I would have done any job and lived in a sewer if it meant never having to let him down. So I kept at it.”

“He always believed in you.”

Richard was quiet. “But then at some point I stopped thinking about him. I can’t remember when the last time was, before today. I can’t even remember the last time we spoke.”

“Joanie’s wedding,” Marion said. “Ten years ago.”

“That was the last time I saw him. But when was the last time I spoke to him? I mean, even just on the phone or something?”

“You’re being too hard on yourself. You know how he was. It wasn’t like he made it easy to stay in touch. When I first moved out here, I used to write all my friends back home letters. Everyone wrote me back. With him, maybe I got a reply once. Once. He just wasn’t a letter writer. And he certainly wasn’t the type to pick up the phone to chat. We didn’t even hear from him when your father died, remember?”

Richard remembered. So many cards and flowers had come in that they had trouble figuring out where to put it all. Other old friends like Ralph Malph and Potsie sent condolences. But there was nothing from Fonzie.

Marion said, “Joanie never mentions his name. I don’t think she and Chachi ever saw him around. You’re not the only one who lost touch, Richard. It’s not your fault. People drift apart. They move on to new selves. It’s what happens.” She continued, “Joanie said there’s a memorial service tomorrow. Back home.”

“I don’t know why you still call it that,” he said.

“I know. Me neither.”

“Are Joanie and Chachi going?”

“They said they weren’t sure they’d be able to get a flight. And, anyway, Arthur would not have wanted them to cut their trip short. She did say you could stay at the house if you wanted to go back. I thought you might.”

“Of course I do. But what about you? You’re not going?”

“I don’t know—I want to, but tomorrow is tutoring.” His mother and Lori Beth volunteered for a charity helping kids who were growing up in rough circumstances stay on track to graduate high school. Tomorrow was their day to help the kids with homework at the community center. “We’ll find replacements. Lori Beth is on the phone with them now.”

“No,” Richard said, “those kids are relying on you. Fonzie would understand more than anybody. It’s okay—saying goodbye is something I can do alone.”

NOTHING WAS MOVING ON THE 405. Richard sat at the wheel, scanning the Corvette’s radio dial, looking for some kind of news about the jam, but there was nothing. He looked at the clock again. Couldn’t be late. On the radio was Prince. It was his daughter’s favorite. He himself wasn’t sure about all that innuendo and raunch. He wasn’t sure about much these days. He had seen the film that Prince had starred in and had liked it more than he thought he would. He had expected a two-hour music video, but it was a drama about family and love and what it meant to pursue your dreams—what it cost. His friend Steven had made him watch it. Called him over to his private theater in his house. It had been nice of Steven to call. It had been months. Maybe longer. At one point he asked Richard what he had been working on. All he had to do was tell him about his project. Steven would have helped him. All he had to do was say the words. But Richard couldn’t tell him. He muttered that he was tinkering with a few different things, then changed the subject to the new project Steven was executive producing, a time-travel film with the kid from Family Ties.

He and Steven had started out around the same time. They were part of a crew of hustlers, strivers, doing whatever they could to make films—Spielberg, Scorsese, Lucas, Cunningham. Back then they all thought it would be Richard who would be the one inviting them over to his private movie theater one day. He had been the first to sell a script, first to get an Oscar nomination. Now almost all of them had become directors on a first-name basis with the world, and he was just another no-name chump stuck in traffic on the 405, running late to lunch with his agent, who held the fate of his project in his hands.

• • •

HE STEERED THE CORVETTE DOWN sunset. The clock said he was okay on time. He relaxed, his mind wandering. He wondered yet again whether or not his agent wanting to meet on a Sunday meant good news. Lori Beth and his mother warned him not to get his hopes up. He could not help it. If the news was bad, legendary Hollywood agent Gleb Cooper would not waste his time with a face-to-face. Especially not on a Sunday. Richard had a good feeling. This would be the day he had been waiting three years for.

He passed Book Soup, where it had all started.

He had been browsing the bargain bins when he came across a remaindered copy of a bizarre-looking novel. Black dust jacket, no art—just the title and author’s name in big, elaborate font that seemed taken off the side of a nineteenth-century circus wagon. It was the black-and-white author photo that most intrigued Richard. Most of them posed very self-seriously, bloodless Ivy Leaguers in tweed. This one, however, named Cormac McCarthy, wore jeans, denim jacket, had uncombed hair. The look on his face was surprised, like someone had shouted his name and snapped his photo when he turned around. He looked like he couldn’t figure out what he was doing on the back of a book jacket. In the background there was not a prestigious college campus or the slick Manhattan skyline but an industrial town. Smokestacks, a bridge, a shipping channel. It looked like the same kind of town Richard had come from.

He took the book to the register. The clerk gave him an approving nod. A good sign. That night at home he started reading.

He could not stop. Three days later, he was still reading. He would have finished the book sooner but the language was like nothing he had ever seen outside of Shakespeare. It was almost something physical to grapple with. He kept having to put the book down and reach for the dictionary. Concatenate. Leptosome. Electuary. They were not even words—they were portals to new worlds.

The story’s grip on Richard was just as mysterious. A man lived on a houseboat in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the 1950s. He seemed to have come from a prestigious family but had been somehow alienated or cast out. A sordid cast of fringe-dwelling characters wandered in and out of his life, pulling him into their small-time hustles and drunken misadventures. Not much happened, on the outside. But on the inside, in the heart and mind of this man, named Suttree, as he tried to hold on to his sense of self in an ever-changing world bent on taking it from him, everything was happening. Everything. Richard understood right away that he knew this character. Felt like he had known him all his life. He could not say why. Not since he was a teenager had he felt this way about a book. Something about this novel brought him back to that vulnerable, openhearted place he had been when he was young. And he wanted desperately to hold on to it. Richard did not know why this character was so appealing to him. Because with Richard’s sports car and slick suits and Spanish Colonial in Sherman Oaks with a pool and detached mother-in-law bungalow in back, he and Suttree would not seem to have a lot in common. He certainly wasn’t a drinker like Suttree. In fact, he rarely drank. Not since one night long ago when he was a young father and the pressure got to him—he took it too far that night and never made that mistake again. But that was what made the book so powerful. It was a kind of art he had never encountered before: the kind that would seem to have nothing to do with you yet still gets to you in ways art that has everything to do with you does not.

When he closed Suttree after the final page, he saw the whole thing in his head, the film adaption he would make of this novel. He saw it from the opening theme through the end credits. I am going to make it, he told himself. He looked at the cover, then the author photo. He felt a warmth growing in his chest. His fingers and hands filling with blood, like they had been asleep but were now waking up. I am. He had to make this film. He was going to write it, and he was going to direct it. It would be his directorial debut.

Not only that—it would be his triumphant return from the brink of extinction.

• • •

IT WAS A STRANGE CHOICE of restaurant. Typically his meetings with Gleb Cooper took place at Musso & Frank, where Gleb had a booth they’d clear out for him upon his arrival, and the maître d’ would accommodate his every need. Once Gleb had ordered catfish. The menu did not include catfish. But Gleb wanted catfish, and Gleb got catfish. Richard could not imagine how they located and prepared one so quickly, but it arrived on time with Richard’s steak tartare. Richard would try to discreetly eyeball the luminaries filling the surrounding tables without Gleb noticing, because if he caught his companion’s gaze wandering like that, he took it as an insult, a challenge, and he would not let it go. He would hold on to it for the rest of the meal. And he would mention it at every meal after. But Richard would tell his grandchildren about that day at Musso’s when Warren Beatty came over to their table to shake Richard’s hand because, Warren Beatty said, he had just heard from a friend at the Academy that Welcome to Henderson County was going to be nominated for an Oscar, and he wanted to shake the hand of the man who had written it.

But this place. It was no Musso’s. It was a forgettable Italian spot on Wilshire called Michelangelo’s. Richard had never heard of it. There wasn’t even a valet. Inside there was no Warren Beatty, nor anybody else, aside from some waiters, a bartender leaning over the want ads of the Sunday Los Angeles Times, and Gleb Cooper in a booth.

He almost did not recognize him, because it was the first time he had ever seen him not wearing a suit. He almost did not even see him at all. He had chosen a booth in the corner, in the shadows. He had his head down, reading the paper, a golf hat pulled low. How old was Gleb? Richard could only guess. He had been a ubiquitous presence in Hollywood longer than anyone could remember. But he still maintained the vitality and power of a man Richard’s age. He always wore custom suits. He was the one who first encouraged Richard to put more effort and consideration into what he wore. “Dressing well is a way of showing respect,” he’d say, “not just for yourself but for everyone else. Give respect, get respect. That’s how it all works. Thar’s all you need to know.” When Richard first came to town twenty years earlier, he wore the one blazer he had, which was ill fitting and badly cut. He had gotten it off the clearance rack at Gimbels back home, and he wore it until the buttons fell off and his elbows just about poked through. He thought he looked sharp, but looking back on it he probably looked like an overgrown prep schooler. When it wasn’t that blazer, it was pastel cardigans—Kmart or Gimbels, whichever was cheaper. Gleb told him he looked like Mr. Rogers. Richard thought it was a compliment, because Mr. Rogers was a good person with a solid character, but it was not. Gleb brought him to the store on Rodeo where he bought his suits, put down a stack of money, and instructed the serious quiet man to take care of his boy. He did. Richard still bought his suits there. Every few years he had them altered to match the changing fashions. Today he was wearing the pale gray double-breasted Calvin Klein. It was Lori Beth’s favorite.

Gleb was dressed for the golf course. Richard could not tell if he was on his way to the links or on his way back from them. It seemed to be an important difference. For the first time, Gleb looked to Richard like an old man, shriveled and small, bent as he was with the paper up close to his face, squinting to read it. Richard grew nervous. But then Gleb looked up and noticed him and his voice came booming across the room with the same energy and enthusiasm as always.

“There he is!” Gleb shouted across the empty restaurant. “There he is! Get over here! Sit, sit!”

Richard went over and slid into the booth. Gleb was drinking coffee. The waiter poured Richard a cup.

“Thanks for meeting me on a Sunday,” Gleb said. “I couldn’t wait to talk to you. I was too excited. Are you coming from church or something? What’s with the suit? You’re making me feel like a schlub.”

“Now you know how the rest of us usually feel,” Richard said.

Gleb grinned. He smoothed his yellow polo shirt, glancing down at it. “On my way to play some golf.”

“No kidding.”

“Sunday’s golf day. No one is allowed to bother me on golf day. I’ve turned down meetings with God on Sunday. No meetings on golf day. That’s my rule. You need rules for yourself. Remember that. Write that down.”

A good sign. A great sign. Richard’s heart was beating hard. It had to be good news. He fought to control the grin on his face. It was a struggle he had been up against since he had arrived in town. His midwestern grin was its own animal—if he did not take care, the thing would eat his entire head. And in this town, a goofy grin like his was a sign of weakness. If you were going to smile, it had to be cool and confident, like Jack Nicholson’s, not unabashed and eager like Richard’s.

Stay cool, Richard told himself. You can celebrate when you get home.

“I’m flattered,” Richard said.

Gleb shrugged. “I’m excited to talk to you. I couldn’t wait.”

“I’m excited too, Gleb. I can’t tell you how happy I am that you see what I see in this project. I know I’ve sort of been on the sidelines the last few years, but—”

“Sort of? Richard, you wouldn’t be more on the sidelines if you were Broadway Joe Namath wearing a Los Angeles Rams jersey in 1977.” Gleb laughed at his own joke.

“Got me,” Richard said, holding his hands up. “Guilty as charged. It’s just that I’ve wanted to get this project right, you know? I’ve wanted to take my time with it, make it perfect, and it’s been very difficult, it’s very dense material, very personal and rich, and, boy, the stream of consciousness of the prose will be very challenging to portray on-screen, but I’m up for it, I really am, I know exactly how to do it.” He started to go into the technical approach he intended to take but cut himself short, seeing Gleb’s eyes glaze over. “Anyway, I want to thank you for sticking with me and believing in me like you have. I cannot wait to get started.”

Gleb said, “Now hold on, Richard, let’s back up. What the hell are you talking about?”

“Suttree,” Richard said, panic creeping in quietly. “We’re here to talk about Suttree, right?”

Gleb let out a deep, wheezing sigh. “Okay,” he said. He waved the waiter over. “Two gin martinis,” he said. “Bone dry and dirty.” The waiter nodded and left.

Richard understood now, all too well. This is why Gleb wanted to meet at such an empty, out-of-the-way restaurant. It wasn’t that he was embarrassed to bring washed-up talent around to his usual haunt. Though that was clearly part of it. No, it was also out of mercy. Gleb had called this meeting planning to kill Richard’s dream but had wanted to spare him the additional pain and suffering of doing it in front of his professional peers, such as they were. He was planning cold-blooded murder en route to a late tee time and didn’t want any witnesses.

“Of course a hit job like this would take place in an Italian restaurant,” Richard said. Gleb did not seem to hear.

“Look, here it is. Okay? I’ve met with everyone about your project. Everyone. From Warner Brothers to a guy named Warner who finances low-budget monster movies for the tax write-off. There is no interest. Zero. I encourage you strongly to forget Suttree. Move on. This should help you do that: I got something for you. That’s why I wanted to meet today. I have a job for you, Richard.”

“If it’s writing a Sorority Slaughterhouse sequel, forget it.”

Richard had written the schlocky slasher film years ago, when he was first starting out. It was the first job Gleb got him. Everyone was doing the same thing, all his friends. Whatever it took. But unlike their films, which were quickly forgotten except among film scholars as their creators ascended to greater things, Sorority Slaughterhouse had become a cult hit. For a time it had been a favorite of midnight screenings. Theater owners used to beg for a sequel. Gleb had pressed Richard on it a few times, but Richard had always refused—especially after the Oscar nomination.

“That was a very profitable picture,” Gleb was saying, pointing his finger at him. “Don’t turn your nose up at it. Be proud of it. You were hungry. You were driven. You were willing to do whatever you had to do. You had grit.”

“What do you mean had? I still do.”

“Sure, sure, yeah, you still do.” Richard could tell Gleb was saying it but he wasn’t meaning it. “But anyway, Richard, no, it’s not that, it’s not Sorority Slaughterhouse.” He moved his eyes to a point just behind Richard’s left shoulder. His face took on an expression of amazement. He raised his hands in the shape of a camera frame, like a cinematographer gauging a shot. Gleb held it there for so long that Richard turned his head to see if something really was back there. Then Gleb announced majestically, jolting his hands at both words for emphasis: “Space Battles.” He moved his hands a little lower then jolted them again as he said, “Original Screenplay by Richard Cunningham.”

Richard sat forward, his grin coming to life again. He knew George, they used to shoot pool together—why hadn’t George called to break the news himself? He didn’t know he was planning another Star Wars. And he certainly had no idea he was thinking of Richard to write it.

“Gleb, that’s incredible news. Incredible! Star Wars! Wow! I have ideas already. I thought the last installment lacked the gravitas of the original. Man, I’d love to restore some of the seriousness and literary value to the franchise.” He let out a whoop that turned the heads of the staff. “Wow, Gleb. I could kiss you. This is exactly what I needed. It’s going to change everything for me.”

“What? No, Richard, no, not Star Wars. Space Battles.”

“I don’t understand.”

“A wicked kingdom, an underdog hero, a foxy princess—and all of it in space.”

“That sounds an awful lot like Star Wars, Gleb.”

“No. Space Battles has two things Star Wars does not.”

“What’s that?”

“Blood and bazoongas.” Richard put his hand over his face. Gleb continued. “Did Star Wars have blood and bazoongas? No it did not. Think about how much more money it would have made if it had. It’s more realistic. It’s realism. That’s your trip, right, Richard?”

The waiter set down the martinis and a small dish of olives. Gleb speared one and put it between his molars and bit. He lifted one of the martinis and drank. “Drink up,” he said, gesturing to the other martini. “Relax. Celebrate. We’re celebrating.”

“No thank you,” Richard said. He and Gleb had worked together fifteen years, and Richard had never been a drinker. Now he was starting to wonder how well his agent knew him. He wondered if Gleb had even read his Suttree script.

Gleb reached over and slid the drink like a chess piece to his own side of the table.

“I don’t want to do this. I want to make Suttree,” Richard told him.

“I know you do. But, look, Richard, the days of a movie like that getting made are over. Ten years ago, yeah, maybe. But now? People just don’t want it. They want people running for their lives and heroes saving the day. They want the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man exploding over Manhattan. They want Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone mowing people down. The rest of your generation figured this out long ago. Look at your buddies. Look at Spielberg. Why can’t you be more like him? Why can’t you just give the people what they want? Now, this job, this is your chance to do that. The kid producing Space Battles, his daddy’s a shah or a sultan or something, I don’t know what he is, but the kid’s a prince. A real live prince. He’s got jets. He’s got jewels. He’s got it all. And he wants to get into pictures, Richard. I know this sounds awful to a writer of your caliber, but know what it sounds like to me? Work. A job. Something you’re sorely in need of.”

Gleb was not wrong. Three years Richard had spent on Suttree. His bank account was low. He and Pepperdine University were square through the rest of 1984, but next year he was not sure where Caroline’s tuition money would come from. And there were still the mortgage payments. The city had just bumped up their property taxes. Downsizing was not an option. Not with Marion.

“How much does it pay?” Richard said, looking down at the table, at his hands gripping his thighs.

“Two hundred,” Gleb said. “Plus five percent on first-dollar gross.”

Richard took a deep breath. “That’s good money.”

“It’s very good money.”

It made Richard think.

“What if I wanted to make my movie myself? How much would it cost?”

Gleb laughed and raised his glass to his lips.

“No, I’m serious. How much?”

“Come on, Richard. What you want to do, you’d have to do it on location. You’d have to fly all the actors and crew out to Tennessee or somewhere that can pass for it. That’s expensive.”

“So you did read my script.”

“Of course I did. And I’ll be honest. I didn’t get it. Neither did anyone else. Also you’d need to hire a director of photography who can figure out how to shoot on a rocking, swaying boat. You’d need to hire a director.”

“No, that’s me, I’ll be the director.”

“No, no investor would go for it. You don’t have the experience. All told, you’d need five million. At least. You’re talking about a major uphill climb. Major. I just don’t have the time to help you with that. Richard, I’m sorry, but that project is finished. Listen to me: I know what I’m talking about. Take this job. Take Space Battles. Knock it out in a few weeks, cash your check, and we’ll figure out the next thing. You really have an interest in directing? I’ll talk to the prince, see if I can get you a PA position or something. Start getting some experience on set.”

Richard glanced around the restaurant. “Funny,” he said, “it’s not at all like I imagined.”

“What’s not?”

“Rock bottom.”

Gleb sighed and said, “It’s not rock bottom. It’s life. Right now this garbage is all I can get for you. This is it. This is where you are. It’s Space Battles or nothing.”

“Can I think about it?”

“Of course. Take a few days. But I need an answer by Saturday. The prince is leaving the country in two weeks, and we need to set up meetings before he goes. And, Richard, when I say it’s Space Battles or nothing, I mean it. If your answer is no, I’m sorry, but there’s nothing more I can do for you. If you want to continue in this business, you’ll have to do it without me.”

• • •

AS HE DROVE HOME HE kept thinking about what Gleb had said about his friends, the filmmakers he had come up with, many of whom were not only successful writers and not only A-list directors but also serious, big-time producers as well. What Gleb had said was true. The successful ones were the ones who had accommodated the sensibilities of the mainstream. They had not been rigid about their aesthetics. They had found a way to do what they wanted to do while appealing to the masses. They had leveraged their commercial work to facilitate their personal work. Maybe that was the way. One for them, then one for you. What was it that kept Richard from just doing that? Why couldn’t he just play the game?

That’s what it was to people in the industry now, to people like Gleb—a game. A zero-sum one. They read Variety for the latest box office figures the way stockbrokers picked apart the Nasdaq reports, the way gamblers chewed up the sports pages looking for any edge. Box office, box scores—they were the same thing to these people. It was not about stories, or film. It was about winners and losers. Nothing in between. He wasn’t naïve. Movies cost money. A lot of money. Production, distribution, marketing. None of it was cheap. And the people who put up the money weren’t doing it out of benevolence. They expected their investment back and then some. He understood all that. But when it came down to it, he still saw cinema as art, not business. If his goal was making money and working with people only interested in the same, he would have become an investment banker.

And then he would have become a patient in a psych ward.

His more successful friends were drawn to the material they did. They weren’t faking it. They had to do their movies the way he had to do Suttree. The question was why did he have to do Suttree? It was a question he could not answer. The enigma of the creative process, he supposed. Even if he could answer it, he would not want to.

But maybe he was naïve. Maybe the reality of making movies was that you had to do what you did not want to do, and he just needed to accept it. Maybe he was still too much of that earnest midwestern kid he once was. Too sincere. Couldn’t lie. Couldn’t fake it. Couldn’t blow smoke. Didn’t smoke. Too clean for this smutty town. Being married to his high school sweetheart didn’t help with this veneer of edgelessness that made him just about disappear. Still madly in love after almost thirty years. Once he went to the Playboy mansion with his friend Brian De Palma, whose latest directorial effort just last weekend opened at $23 million (but who was counting?). It was not Richard’s scene. He’d spent the whole party hiding out alone in Hefner’s library, reading his first edition The Great Gatsby. Now that was Richard’s idea of a good time. With charisma like that, maybe it was no wonder he was overlooked.

Then there was the fact that he still lived with his mother.

It had not been planned. After his father passed, Marion decided to just stay out here. She and Howard had been talking about moving to Los Angeles anyway. The weather was nicer, the pace was more mellow, and it would put them closer to their grandkids. It would be better for Howard’s heart.

The cardiologist had told them not to make that trip. There was an appointment coming up. A very important appointment. It would give them a better idea of what was wrong this time. Richard begged his father to listen to the doctor. And he could not get them into the ceremony anyway—they would have to watch on TV from Richard and Lori Beth’s house. “But what if you win?” Howard kept saying. Richard told him he wouldn’t win, there was no chance, not up against Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. But Howard would not listen. “Think it’s every day my son gets nominated for an Oscar?” He was going to be there in person, no matter what. Richard never for a moment thought he would win, but he was still disappointed when it was not his name they called. Coming home with Lori Beth that night and having his parents there, seeing how proud they were of him, supporting him the way they always had when he was a kid—he was glad they had come. He was relieved.

They all stayed up late that night, Howard telling Richard his favorite parts of Welcome to Henderson County. It had not played in Milwaukee. They’d had to drive two and a half hours in the snow to see it in Chicago. When it ended, they rose from their seats and gave it a standing ovation.

“After the show,” said Marion, “your father stood outside the theater door, shaking everyone’s hands and thanking them for coming, and telling them the writer was his son. He even started signing autographs.”

Howard shrugged. “They asked me for them.”

Before they all turned in that night, Howard stopped Richard at the foot of the stairs. He took his son’s face in his hands. “I owned a hardware store,” he said.

Richard was confused. “Yeah, Dad,” he said. “I know that.”

“A hardware store. Nails. Wood.” Richard did not say anything. Howard’s eyes were glistening, turning red. Richard just looked back into them. “And my son’s an artist. A hardware store and my son’s an artist.” Richard was an inch taller than his father. Howard pulled his head down and kissed him on top of it. “My son’s an artist.”

They were supposed to fly back in the morning. Howard did not come downstairs. Marion kept calling up to him, “We’re going to miss our flight!” Finally she went up. Down in the kitchen, Richard and Lori Beth heard her saying his name. Over and over she said it. Soon she was yelling it. Yelling for them.

They buried Howard in Los Angeles. To keep him near his beloved grandkids. Marion took over the empty in-law suite out back by the pool and gave the house in Milwaukee to Joanie and her husband, Chachi.

“My son’s an artist.” Richard never forgot it. Maybe those words were why he could not bring himself to play the game, to bend and concede.

Richard was lost in these thoughts. He did not see the red light until it was almost too late. He slammed the brakes to avoid making roadkill out of two young women crossing the street. The redhead slammed her palms onto the Corvette’s hood.

“Hey man!” she shouted. But it wasn’t a she at all. “Get out of the car!” the man was saying.

“Be cool, Axl,” said the other one, also a man, who wore a top hat. He pulled Axl away, and they crossed the street. Richard watched them walk off, stapling flyers to every telephone pole they passed, advertisements for their band. He remembered when he used to have that faith and conviction about what he was doing. That grit. He even used to have that red hair. All of it had faded these years under the Southern California sun.

Enjoy it while it lasts, he said to himself.

Then the light turned green and he headed home, to deliver the bad news to Lori Beth and his mother.

• • •

AFTER MORE THAN A DECADE in Los Angeles, Marion Cunningham had developed a passion for crystals, star charts, and yoga. She had stopped cutting and coloring her hair after her friends at the holistic health spa had told her that it was where her life force was stored and that toxins from the chemicals in hair dye could seep into the scalp and blood. They tried to convince her about reincarnation, but she couldn’t be sold, though she did believe it was a beautiful concept she wished was true. Mostly she was fanatical about her macrobiotic vegetarian diet—she was not allowed to cook for Richard and Lori Beth because they couldn’t stand all that tofu and raw alfalfa—but when her grandkids were home she would cook anything they wanted, even meat. It was fine with Richard that she had become so earthly and nonmaterialistic. In her former life as a Milwaukee homemaker, when her days were spent chopping food and sweeping floors and carrying around children and propping herself up, she had taught herself to live without wanting more.

But walking into the house in Sherman Oaks, he was in no mood to receive a lecture on how Mercury being in retrograde had caused the meeting with Gleb to go badly. She and Lori Beth had both warned him not to get his hopes up. He had told them they were wrong. The fact that they were right made it all worse. When he found them in the high-ceilinged living room, sitting on the facing couches in grim silence, he wanted to be anywhere but where he was.

“You were right,” he said. “Okay? Suttree is done. I was insane for thinking it would ever happen. Of course no one wants a movie like that. And I really believed they might let me direct it? Three years of my life—gone.”

Saying it out loud made him dizzy.

“Oh, Richard,” Lori Beth said, looking at him with pity. It was the last thing he needed.

“Sit down, honey,” Marion said. She had been crying. It made him realize that Lori Beth had been too. They knew he would be coming home with bad news, he thought. They knew he was going to be destroyed at that meeting, and they let him go into it anyway, they didn’t try to shake him out of his delusion.

He turned away from them. “No,” he said. He started walking out of the living room. “I need to take a walk or something.”

“Richard,” Marion said, “sit down.” It had been years since he had heard such assertiveness in her voice. He came back and sat in an armchair.

“Look,” he said, “I appreciate your sympathy. I really do. But—”

“Joanie called,” Marion said.

“From Tahiti?” Richard said. His sister and Chachi were there for their tenth wedding anniversary. “Why? Is everything okay?”

Marion cleared her throat and looked at Lori Beth who said, “She was calling about Fonzie.”

It took him a moment. The context was too displaced. It was not the name of a producer or an actor or a director or a studio executive. So it did not seem to be the name of anyone. “Fonzie,” he said.

Lori Beth breathed deeply and tried to explain. “Last Thursday night, he was driving across Hoan Bridge and . . .” She could not finish.

“And what?” She just shook her head no. She put her hand over her eyes.

“Richard,” Marion said. “He was in an accident.”

“What happened?”

“Joanie didn’t know all the details. She only knew what Al told Chachi when he called to tell them: he lost control of his motorcycle and crashed into the guardrail. He went flying over the handlebars, over the guardrail, and down into the lake. They’ve been looking, but they haven’t found it.”

“What do you mean it?”

“The body, Richard,” Marion said quietly, sweetly. “His body.”

Richard was shaking his head side to side, unable to stop. He moved to the edge of his chair, stood up, then sat back down. Lori Beth reached over and put her hand on his. She looked at him with crying eyes.

“I’m sorry,” she was saying.

There was a mirror on the wall. Richard could see himself all too clearly in it. Red eyes. Crow’s feet. Steadily receding hairline. Inexplicable wobble of flesh beneath his chin—the beginnings of an old man’s neck. Each man has that moment in his life when he looks in a mirror and sees for the first time the uninteresting old man young women see when they look at him—if they look at him, which, because he’s an old man, they do not. This was that moment for Richard Cunningham. Not the day he moved Richie Jr. into his first apartment, and not the day he dropped Caroline off at college. This day. The day he realized middle age had met him like a two-by-four to the face.

The day he learned his best friend from childhood was dead.

• • •

MARION AND LORI BETH LEFT him sitting there in the living room to give him some time alone. He was still there two hours later when Marion returned to check on him. She stood beside him. “You should eat.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“I’ll make you something. No tofu, I promise.”

“No thanks, Mom.”

She sat on one of the sofas.

“Remember all the things I did just to make a living?” he said. “Lori Beth’s and my first few years out here trying to make it?”

“I remember when you were selling watches over the telephone from one of those seedy call centers in Encino, was it?”

“And that was the best one. And all the apartments Lori Beth and I lived in. All those dumps. Mice. Busted plumbing. The police asking about our neighbors.”

“I used to worry about you.”

“We were fine. It was never dangerous.”

“I wasn’t worried about your safety, I was worried about whether you were happy.”

“I was. Those were some of the best days of my life. We went through times that were so uncertain and so terrifying and made us ask ourselves every day if we should call it quits and just go back home and get more practical jobs, play it safe. But whenever I thought about quitting, you know what I thought about to keep myself going? I thought of Arthur Fonzarelli. I imagined what he would say if I went back to Milwaukee and told him I had quit. I pictured the look in his eyes. How disappointed he would be in me if I ever told him I had stopped believing in myself. He wouldn’t have said anything. He would have just looked at me a certain way. I can almost see it now. I would have done any job and lived in a sewer if it meant never having to let him down. So I kept at it.”

“He always believed in you.”

Richard was quiet. “But then at some point I stopped thinking about him. I can’t remember when the last time was, before today. I can’t even remember the last time we spoke.”

“Joanie’s wedding,” Marion said. “Ten years ago.”

“That was the last time I saw him. But when was the last time I spoke to him? I mean, even just on the phone or something?”

“You’re being too hard on yourself. You know how he was. It wasn’t like he made it easy to stay in touch. When I first moved out here, I used to write all my friends back home letters. Everyone wrote me back. With him, maybe I got a reply once. Once. He just wasn’t a letter writer. And he certainly wasn’t the type to pick up the phone to chat. We didn’t even hear from him when your father died, remember?”

Richard remembered. So many cards and flowers had come in that they had trouble figuring out where to put it all. Other old friends like Ralph Malph and Potsie sent condolences. But there was nothing from Fonzie.

Marion said, “Joanie never mentions his name. I don’t think she and Chachi ever saw him around. You’re not the only one who lost touch, Richard. It’s not your fault. People drift apart. They move on to new selves. It’s what happens.” She continued, “Joanie said there’s a memorial service tomorrow. Back home.”

“I don’t know why you still call it that,” he said.

“I know. Me neither.”

“Are Joanie and Chachi going?”

“They said they weren’t sure they’d be able to get a flight. And, anyway, Arthur would not have wanted them to cut their trip short. She did say you could stay at the house if you wanted to go back. I thought you might.”

“Of course I do. But what about you? You’re not going?”

“I don’t know—I want to, but tomorrow is tutoring.” His mother and Lori Beth volunteered for a charity helping kids who were growing up in rough circumstances stay on track to graduate high school. Tomorrow was their day to help the kids with homework at the community center. “We’ll find replacements. Lori Beth is on the phone with them now.”

“No,” Richard said, “those kids are relying on you. Fonzie would understand more than anybody. It’s okay—saying goodbye is something I can do alone.”

Recenzii

"Who Killed the Fonz? stands tall in a field of television property revivals. James Boice deftly mixes the broad comedy of the TV series with classic noir elements, resulting in an unexpectedly emotional rollercoaster ride that's more than a novelty. Happy Days are here again!" —Andrew Shaffer, author of the New York Times bestseller Hope Never Dies: An Obama Biden Mystery

“I must confess that I never watched a single episode of Happy Days during its ten-year run, but reading Who Killed The Fonz? made me wish I had. Thank you, James Boice, not only for giving us a fast-paced, entertaining novel, but for reminding us in these corrupt Orwellian/Tower of Babel times we live in now, that not so many years ago "friending" someone meant much more than just clicking on a mouse, and that doing the right thing, no matter the risk, was looked upon as honorable and something to be proud of rather than as a sucker’s game.” —Donald Ray Pollock, author of The Devil All the Time and The Heavenly Table

“James Boice has achieved a magic kind of alchemy, exhuming beloved characters from our collective consciousness and gifting them with a fate, a future, and poignant inner lives. Who Killed the Fonz? is the best kind of pop-culture hypothetical — one that imagines, with heart, wit, and smarts, what happens when the Happy Days fade and real life begins.” — Adam Sternbergh, Edgar-nominated author of The Blinds

"A wildly inventive and entertaining novel." —Booklist

"Shamelessly entertaining..." —Kirkus Reviews

"Readers yearning for simpler times will enjoy this trip down memory lane, which is as comforting as an episode of Happy Days." —Publishers Weekly

“I must confess that I never watched a single episode of Happy Days during its ten-year run, but reading Who Killed The Fonz? made me wish I had. Thank you, James Boice, not only for giving us a fast-paced, entertaining novel, but for reminding us in these corrupt Orwellian/Tower of Babel times we live in now, that not so many years ago "friending" someone meant much more than just clicking on a mouse, and that doing the right thing, no matter the risk, was looked upon as honorable and something to be proud of rather than as a sucker’s game.” —Donald Ray Pollock, author of The Devil All the Time and The Heavenly Table

“James Boice has achieved a magic kind of alchemy, exhuming beloved characters from our collective consciousness and gifting them with a fate, a future, and poignant inner lives. Who Killed the Fonz? is the best kind of pop-culture hypothetical — one that imagines, with heart, wit, and smarts, what happens when the Happy Days fade and real life begins.” — Adam Sternbergh, Edgar-nominated author of The Blinds

"A wildly inventive and entertaining novel." —Booklist

"Shamelessly entertaining..." —Kirkus Reviews

"Readers yearning for simpler times will enjoy this trip down memory lane, which is as comforting as an episode of Happy Days." —Publishers Weekly