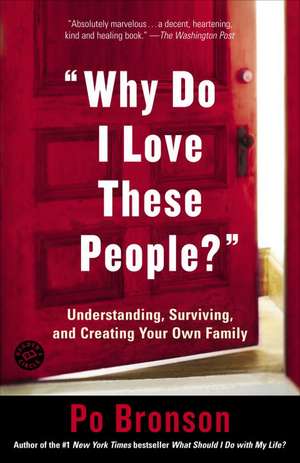

Why Do I Love These People?: Understanding, Surviving, and Creating Your Own Family

Autor Po Bronsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2006

In the pages of Why Do I Love These People?, Po Bronson takes us on an extraordinary journey.

It begins on a river in Texas, where a mother gets trapped underwater and has to bargain for her own life and that of her kids.

Then, a father and his daughter return to their tiny rice-growing village in China, hoping to rekindle their love for each other inside the walls of his childhood home.

Next, a son puts forth a riddle, asking us to understand what his first experience of God has to do with his Mexican American mother.

Every step–and every family–on this journey is real.

Calling upon his gift for powerful nonfiction narrative and philosophical insight, Bronson explores the incredibly complicated feelings that we have for our families. Each chapter introduces us to two people–a father and his son, a daughter and her mother, a wife and her husband–and we come to know them as intimately as characters in a novel, following the story of their relationship as they struggle resiliently through the kinds of hardships all families endure.

Some of the people manage to save their relationship, while others find a better life only after letting the relationship go. From their efforts, the wisdom in this book emerges. We are left feeling emotionally raw but grounded–and better prepared to love, through both hard times and good time.

In these twenty mesmerizing stories, we discover what is essential and elemental to all families and, in doing so, slowly abolish the fantasies and fictions we have about those we fight to stay connected to.

In Why Do I Love These People?, Bronson shows us that we are united by our yearnings and aspirations: Family is not our dividing line, but our common ground.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 93.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 140

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.92€ • 18.83$ • 15.06£

17.92€ • 18.83$ • 15.06£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812972429

ISBN-10: 0812972422

Pagini: 386

Ilustrații: PHOTOGRAPHS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 148 x 193 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812972422

Pagini: 386

Ilustrații: PHOTOGRAPHS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 148 x 193 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Po Bronson travels the country recording the stories of real people who have struggled to answer life’s biggest questions. To learn more about his research, visit www.pobronson.com. He is the author of five books–two novels and three works of nonfiction–and he has written for television, magazines, radio, and newspapers, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and NPR’s Morning Edition. He lives in San Francisco with his family.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Cook’s Story

We’ve all lost something along the way.

In Jennifer Louie’s case, what she had lost was a belief that her family was a fundamentally essential thing, a meaningful purpose worth her devotion, a principle on which to build her life. Family is like Religion: There are all kinds, but when you get right down to it, you either believe, or you’re not sure, or you think it’s a crock of hooey. Jen had lost her belief. She had it in China, and she lost it when she came to America. These things happen—she was moving on. She was in the right place to lose it: The United States of America has seventy-six million great families with roots around the world, but it’s also one of the best places in which to move on after losing belief. It can be done here. Those “Not Sure” have plenty of company.

Then, unexpectedly, it came back. Her belief. It came back when she got to know her father, James, but not as her father, just as a man, a human being with feelings. She found herself loving him again, with a respect she’d not had in twenty years.

This is their story.

I had actually met Jennifer before.

“Do you remember?” she asked.

“I still have your old business card,” I recalled truthfully. We would bump into each other at a South of Market club where my best friend and I used to swing-dance. What I remembered about Jen was that she spoke very directly about her emerging career as a television producer. She was ambitious and sharp. And this was memorable, because we were in a club where (1) businessy career conversations seemed out of place, not to mention hard to hear, and (2) Jen was working as a Lucky Strike cigarette girl, in costume, giving away cigarettes. Her second job. It was amusing to listen to the beautiful, fiercely independent Chinese Lucky Strike girl going on about her successful day job for a cable channel in the big city. It always stuck in my memory, a multiculti Mary Tyler Moore moment. Yes, she was in Lucky Strike costume, but she moved around the nightclub with the body language of a manager in an office, armed with business cards, never missing a chance to network. When she mentioned her family, she always painfully waved the topic away. “They just don’t get me,” she would say, or “They don’t approve of what I’m doing with my life,” or “They’re living their life, I’m living mine.” Unable to please them, she’d stopped trying. She treasured her career passion like a good secret, it being the only part of her life that was hers alone to ruin or shape into something grand.

Then, one day some six years later, after I made a presentation at a business conference (about the heroic courage required to find a meaningful career, no less), Jennifer came up to me, wondering if I remembered her. She said she’d just moved back from New York. There was something different about her, a peacefulness to equal her confidence. It intrigued me. We agreed to meet for a glass of wine after work the next week.

With Jen, there’s so much to attract the eye. She puts the double H in hip-hop. Blond streaks highlight her black hair. A mountain lion tooth dangles from her leather choker. Metallic powder-blue eyeshadow, umber lip liner, and rose-tinted sunglasses add color to her visage. Pin-striped pants, a snug T-shirt, and black boots with two-inch heels proudly show off her curves. But while I noticed these details, my eye fixed on the one accessory that didn’t fit. On her left wrist was a delicate bracelet of beaded hooks, with a single gold heart dangling from the chain. It was solid gold, but somehow raw—shiny, but without the luster of contemporary jewelry. It looked fragile. This was not the sort of bracelet folks bought in Soho. An heirloom?

“Is it a locket?” I asked, referring to the single gold heart.

“No, it’s not a locket,” Jen answered, “but it’s very perceptive of you to notice this, of all things. It never leaves my wrist.”

“There’s more to it than that, I can tell from your voice.”

“I didn’t see this bracelet for twenty years. Now a whole story is represented to me by this bracelet.”

A locket after all.

Over the next year I spent many afternoons with Jen and her father, James. He’s fifty-three, relaxed in the face, but often looks down in contemplation. He is not a formal man; sometimes I found him in a Sacramento Kings T-shirt and flip-flops, at other times in an open-necked dress shirt and dress slacks, but shoeless. We laughed together, and hugged unself-consciously, which was not something Jen had seen him do with anyone in America except his immediate family. I think of physical affection as a sort of fourth dimension: You can get through life without ever knowing it’s there, but it sure adds something to the experience when you open up to it. I guess James was demonstrative with me as a way of reaching across the limitations of language. When narrating facts, he spoke Cantonese, with Jen translating, saving his sparse and humble English for the very few concepts or feelings he was desperate to communicate. Often he needed to say it to Jen once, get the English translation from her, shake that off like a pitcher might a catcher’s sign, modify it, test a better word on Jen, and then be the one who delivered this translation to me, warm from the oven of his heart. When communication slows down—when the data rate slows down—we can feel more. In fact, it was my practice to go over the same material repeatedly, often forcing a source to retell the story five to eight times until he had lost track of his codified “safe” version and was spilling out untapped rememberances that made him feel it all again.

At one point James had said something that made him laugh almost silently to himself. Because laughter is infectious among friends, I giggled impulsively.

“What’d he say?” I asked Jen.

She repeated in English, amused, “This must be a world record.”

“For what?”

“For the longest anyone has ever listened to a fry cook.”

Before leaving China, they had hid the gold.

The gold had been forged into necklaces, bracelets, and rings. Their fortune fit into the flat, round plastic cases of two powder compacts, their makeshift treasure chest. One of the bracelets was a family heirloom passed down from a great-grandmother—a string of beaded hooks with a single small gold heart dangling off the chain. It fell over on itself in a double loop in the compact case. A fold of silk kept the jewelry from rattling.

It’s traditional for migrating families to convert their savings to gold, since it’s a reliable currency accepted everywhere. But James Louie didn’t bring the gold with him to California. He brought all his cash, five hundred dollars, but he hid the gold in the house he was leaving. In this moment—in this very untraditional and revealing decision—what heartwarming, charmingly hopeless love of home! James Louie stashed the gold because he fully intended to come back. Frequently! He anticipated making enough money in America to return every few summers on vacation. The house he, his son, and his daughter had been born in—a brick-and-cinder hovel in the rice commune of Tai San (house number 18 in case you’re ever in the neighborhood)—would become his summer home. While there was no plumbing whatsoever (they scooped water from the river) and no stove (cooking instead over small fires of fig leaves and branches), the house had been supplied with electrical current ten years before, and recently James had wired a television—the only one in the village. On Thursday nights James’s daughter, Jennifer, all of eight years old, would sell tickets to people from neighboring villages to watch the only Chinese television show they could receive.

James had farmed rice almost every day of his twenty-nine-year life in a village where barter, not money, was the primary currency. He had been to high school, where he had met his wife, Kim, but that was it. His peasant’s life did not resemble that of the doctors and academicians who had been thrown into the rice fields during the Cultural Revolution, torn from their children and spouses. Even if James—like everyone else—wanted a ticket out, communism had never scarred his family. Occasionally the communists showed up and hauled away the stored rice. They were not an everyday presence. They let James plant vegetables in an unclaimed corner of a field and keep a pigsty and chicken coop across the street. James Louie was a simple man. His love for Tai San was not complicated.

So he ordered the pots to be left hanging from their hooks. He told his family to take some clothes, but to leave others folded neatly in chests. The heart and soul of the home was an altar of framed photographs of family members going back a few generations, with James’s mother dominating in the middle. He harvested very little from the altar, only the smallest mementos.

“I will be back, Mother,” he said, bowing before her photo.

This was July 1980. He was in southern China, 120 miles from Canton City, 200 miles from Hong Kong, 7,100 miles from California.

He slipped the gold into the red compacts and pried loose a wood panel from the brick. Jimmying a white block forward with his fingers, he opened his secret hiding place. Behind the wall was a wormhole just wide enough for his arm to snake down into. At the end of his reach, he wedged the gold. (He was the tallest man in the village, thus his arms were longest. The few extra inches might make a difference.)

The whitewashed brick and wood panel were set back in place. The door to number 18 was locked, and James entrusted the lock’s skeleton key to his best friend. They paid one last visit to his mother’s grave in the rice fields, and then James told his grandfather—the man, now in his eighties, who’d raised him—that he would return the following summer. James held back the tears and the fear that it would probably be three or four years before he returned. He knew that he might be seeing his beloved grandfather for the last time.

Jennifer had been given a pink princess dress and a Dorothy Hamill haircut for the occasion. (Somehow, the Dorothy Hamill bob with blunt bangs had made it to China.) Jennifer remembers fretting about whether this American ice skater’s haircut would be sufficient to allow her to fit in, but her father seemed confident in what he was doing. In their culture there was no such thing as questioning your father. “Your cousins will teach you,” he promised. His own father, sister, and brother had gone to San Francisco twenty years earlier. By now they were thriving. The family would smooth their transition.

They didn’t. The family was caught up in their own lives.

They treated the new Louies rudely, mocked them for not speaking English, and overlooked them at Christmas. The new arrivals were never “emotionally claimed,” to use James’s phrase.

Way too soon the new Louies were on their own, living in Sacramento, running restaurants, sacrificing, trying to assimilate, hoping their children would attend college, maybe even—if they were a very lucky family—the University of California at Berkeley. Which is exactly where Jennifer went. All that unfolded like the great American Dream, but they never knew it would work out like that. In any given moment, they were terrified and powerless and felt like failures and took it out on one another in the way only families can: cruelly. On paper they appeared a success, but financially the extreme hardship never relented. Emotionally, they became dire enemies.

James: “The father my daughter knew was bitter . . . controlling . . . rough.” He knows this now, abuse being an American concept he’s had to learn.

Jen added, “He also now knows it was illegal to have left his children at home unsupervised every afternoon and evening.”

James corrected her, “No, I knew then. I knew.”

Jen absorbed this: then, worried her father was shouldering all the blame, offered her own confession: “The daughter my father knew was selfish, she thought only of herself, she was embarrassed by her Chinese heritage, she refused to speak in Cantonese to her parents anywhere in public. In ninth grade I won an award for a poem I had written about my great-grandfather unwillingly letting us go on our last day in China. I didn’t even invite my parents to the awards ceremony. I told myself it was because they couldn’t come anyway, but the truth was, I was afraid they’d show up in their communist pajamas and embarrass me.” Jen dug out the poem from a paperback book her high school had published. I read it quickly. I sensed James’s interest. I handed the book to him. He read it as only a man fifteen years too late can read a poem.

In her poems and journals young Jen had started to carve out her own secret life. In high school she lied in order to see boys and go to dances. Her parents sensed all this, and in their minds they had already lost her. Nothing they said or did could keep her from becoming Americanized. When they telephoned her at Berkeley, all they heard was “Yeah Dad, yeah Mom, okay, yeah.”

In graduation photos, forced to stand with her parents, she looks positively gloomy.

Then the ultimate indignity: After college their daughter went to work for pennies as a producer for a new cable show, Q-TV, an issues and entertainment show for gays and lesbians. They knew their daughter wasn’t a lesbian, but if she had been that might have made more sense. Occasionally she showed up with videotapes, proud of her hard work, hoping to share.

Imagine this scene! Imagine what her parents were feeling. They left their homeland at middle age, their siblings sabotaged their attempt to assimilate, they both worked double shifts for fourteen years to put their daughter into one of the best colleges in America, and what did she do with this incredible opportunity? Not buy a house, not buy a new car, but rather—she created a great seven-minute segment on the hot new gay comic!

She had no steady boyfriend, no real income, but she’d gone to Palm Springs and sat by the pool for two days interviewing lesbian conventioneers about how, exactly, they practice safe sex!

And did she even get paid for this work? Not enough that she didn’t have to sell cigarettes to make her rent!

Oh, they were thrilled.

From the Hardcover edition.

We’ve all lost something along the way.

In Jennifer Louie’s case, what she had lost was a belief that her family was a fundamentally essential thing, a meaningful purpose worth her devotion, a principle on which to build her life. Family is like Religion: There are all kinds, but when you get right down to it, you either believe, or you’re not sure, or you think it’s a crock of hooey. Jen had lost her belief. She had it in China, and she lost it when she came to America. These things happen—she was moving on. She was in the right place to lose it: The United States of America has seventy-six million great families with roots around the world, but it’s also one of the best places in which to move on after losing belief. It can be done here. Those “Not Sure” have plenty of company.

Then, unexpectedly, it came back. Her belief. It came back when she got to know her father, James, but not as her father, just as a man, a human being with feelings. She found herself loving him again, with a respect she’d not had in twenty years.

This is their story.

I had actually met Jennifer before.

“Do you remember?” she asked.

“I still have your old business card,” I recalled truthfully. We would bump into each other at a South of Market club where my best friend and I used to swing-dance. What I remembered about Jen was that she spoke very directly about her emerging career as a television producer. She was ambitious and sharp. And this was memorable, because we were in a club where (1) businessy career conversations seemed out of place, not to mention hard to hear, and (2) Jen was working as a Lucky Strike cigarette girl, in costume, giving away cigarettes. Her second job. It was amusing to listen to the beautiful, fiercely independent Chinese Lucky Strike girl going on about her successful day job for a cable channel in the big city. It always stuck in my memory, a multiculti Mary Tyler Moore moment. Yes, she was in Lucky Strike costume, but she moved around the nightclub with the body language of a manager in an office, armed with business cards, never missing a chance to network. When she mentioned her family, she always painfully waved the topic away. “They just don’t get me,” she would say, or “They don’t approve of what I’m doing with my life,” or “They’re living their life, I’m living mine.” Unable to please them, she’d stopped trying. She treasured her career passion like a good secret, it being the only part of her life that was hers alone to ruin or shape into something grand.

Then, one day some six years later, after I made a presentation at a business conference (about the heroic courage required to find a meaningful career, no less), Jennifer came up to me, wondering if I remembered her. She said she’d just moved back from New York. There was something different about her, a peacefulness to equal her confidence. It intrigued me. We agreed to meet for a glass of wine after work the next week.

With Jen, there’s so much to attract the eye. She puts the double H in hip-hop. Blond streaks highlight her black hair. A mountain lion tooth dangles from her leather choker. Metallic powder-blue eyeshadow, umber lip liner, and rose-tinted sunglasses add color to her visage. Pin-striped pants, a snug T-shirt, and black boots with two-inch heels proudly show off her curves. But while I noticed these details, my eye fixed on the one accessory that didn’t fit. On her left wrist was a delicate bracelet of beaded hooks, with a single gold heart dangling from the chain. It was solid gold, but somehow raw—shiny, but without the luster of contemporary jewelry. It looked fragile. This was not the sort of bracelet folks bought in Soho. An heirloom?

“Is it a locket?” I asked, referring to the single gold heart.

“No, it’s not a locket,” Jen answered, “but it’s very perceptive of you to notice this, of all things. It never leaves my wrist.”

“There’s more to it than that, I can tell from your voice.”

“I didn’t see this bracelet for twenty years. Now a whole story is represented to me by this bracelet.”

A locket after all.

Over the next year I spent many afternoons with Jen and her father, James. He’s fifty-three, relaxed in the face, but often looks down in contemplation. He is not a formal man; sometimes I found him in a Sacramento Kings T-shirt and flip-flops, at other times in an open-necked dress shirt and dress slacks, but shoeless. We laughed together, and hugged unself-consciously, which was not something Jen had seen him do with anyone in America except his immediate family. I think of physical affection as a sort of fourth dimension: You can get through life without ever knowing it’s there, but it sure adds something to the experience when you open up to it. I guess James was demonstrative with me as a way of reaching across the limitations of language. When narrating facts, he spoke Cantonese, with Jen translating, saving his sparse and humble English for the very few concepts or feelings he was desperate to communicate. Often he needed to say it to Jen once, get the English translation from her, shake that off like a pitcher might a catcher’s sign, modify it, test a better word on Jen, and then be the one who delivered this translation to me, warm from the oven of his heart. When communication slows down—when the data rate slows down—we can feel more. In fact, it was my practice to go over the same material repeatedly, often forcing a source to retell the story five to eight times until he had lost track of his codified “safe” version and was spilling out untapped rememberances that made him feel it all again.

At one point James had said something that made him laugh almost silently to himself. Because laughter is infectious among friends, I giggled impulsively.

“What’d he say?” I asked Jen.

She repeated in English, amused, “This must be a world record.”

“For what?”

“For the longest anyone has ever listened to a fry cook.”

Before leaving China, they had hid the gold.

The gold had been forged into necklaces, bracelets, and rings. Their fortune fit into the flat, round plastic cases of two powder compacts, their makeshift treasure chest. One of the bracelets was a family heirloom passed down from a great-grandmother—a string of beaded hooks with a single small gold heart dangling off the chain. It fell over on itself in a double loop in the compact case. A fold of silk kept the jewelry from rattling.

It’s traditional for migrating families to convert their savings to gold, since it’s a reliable currency accepted everywhere. But James Louie didn’t bring the gold with him to California. He brought all his cash, five hundred dollars, but he hid the gold in the house he was leaving. In this moment—in this very untraditional and revealing decision—what heartwarming, charmingly hopeless love of home! James Louie stashed the gold because he fully intended to come back. Frequently! He anticipated making enough money in America to return every few summers on vacation. The house he, his son, and his daughter had been born in—a brick-and-cinder hovel in the rice commune of Tai San (house number 18 in case you’re ever in the neighborhood)—would become his summer home. While there was no plumbing whatsoever (they scooped water from the river) and no stove (cooking instead over small fires of fig leaves and branches), the house had been supplied with electrical current ten years before, and recently James had wired a television—the only one in the village. On Thursday nights James’s daughter, Jennifer, all of eight years old, would sell tickets to people from neighboring villages to watch the only Chinese television show they could receive.

James had farmed rice almost every day of his twenty-nine-year life in a village where barter, not money, was the primary currency. He had been to high school, where he had met his wife, Kim, but that was it. His peasant’s life did not resemble that of the doctors and academicians who had been thrown into the rice fields during the Cultural Revolution, torn from their children and spouses. Even if James—like everyone else—wanted a ticket out, communism had never scarred his family. Occasionally the communists showed up and hauled away the stored rice. They were not an everyday presence. They let James plant vegetables in an unclaimed corner of a field and keep a pigsty and chicken coop across the street. James Louie was a simple man. His love for Tai San was not complicated.

So he ordered the pots to be left hanging from their hooks. He told his family to take some clothes, but to leave others folded neatly in chests. The heart and soul of the home was an altar of framed photographs of family members going back a few generations, with James’s mother dominating in the middle. He harvested very little from the altar, only the smallest mementos.

“I will be back, Mother,” he said, bowing before her photo.

This was July 1980. He was in southern China, 120 miles from Canton City, 200 miles from Hong Kong, 7,100 miles from California.

He slipped the gold into the red compacts and pried loose a wood panel from the brick. Jimmying a white block forward with his fingers, he opened his secret hiding place. Behind the wall was a wormhole just wide enough for his arm to snake down into. At the end of his reach, he wedged the gold. (He was the tallest man in the village, thus his arms were longest. The few extra inches might make a difference.)

The whitewashed brick and wood panel were set back in place. The door to number 18 was locked, and James entrusted the lock’s skeleton key to his best friend. They paid one last visit to his mother’s grave in the rice fields, and then James told his grandfather—the man, now in his eighties, who’d raised him—that he would return the following summer. James held back the tears and the fear that it would probably be three or four years before he returned. He knew that he might be seeing his beloved grandfather for the last time.

Jennifer had been given a pink princess dress and a Dorothy Hamill haircut for the occasion. (Somehow, the Dorothy Hamill bob with blunt bangs had made it to China.) Jennifer remembers fretting about whether this American ice skater’s haircut would be sufficient to allow her to fit in, but her father seemed confident in what he was doing. In their culture there was no such thing as questioning your father. “Your cousins will teach you,” he promised. His own father, sister, and brother had gone to San Francisco twenty years earlier. By now they were thriving. The family would smooth their transition.

They didn’t. The family was caught up in their own lives.

They treated the new Louies rudely, mocked them for not speaking English, and overlooked them at Christmas. The new arrivals were never “emotionally claimed,” to use James’s phrase.

Way too soon the new Louies were on their own, living in Sacramento, running restaurants, sacrificing, trying to assimilate, hoping their children would attend college, maybe even—if they were a very lucky family—the University of California at Berkeley. Which is exactly where Jennifer went. All that unfolded like the great American Dream, but they never knew it would work out like that. In any given moment, they were terrified and powerless and felt like failures and took it out on one another in the way only families can: cruelly. On paper they appeared a success, but financially the extreme hardship never relented. Emotionally, they became dire enemies.

James: “The father my daughter knew was bitter . . . controlling . . . rough.” He knows this now, abuse being an American concept he’s had to learn.

Jen added, “He also now knows it was illegal to have left his children at home unsupervised every afternoon and evening.”

James corrected her, “No, I knew then. I knew.”

Jen absorbed this: then, worried her father was shouldering all the blame, offered her own confession: “The daughter my father knew was selfish, she thought only of herself, she was embarrassed by her Chinese heritage, she refused to speak in Cantonese to her parents anywhere in public. In ninth grade I won an award for a poem I had written about my great-grandfather unwillingly letting us go on our last day in China. I didn’t even invite my parents to the awards ceremony. I told myself it was because they couldn’t come anyway, but the truth was, I was afraid they’d show up in their communist pajamas and embarrass me.” Jen dug out the poem from a paperback book her high school had published. I read it quickly. I sensed James’s interest. I handed the book to him. He read it as only a man fifteen years too late can read a poem.

In her poems and journals young Jen had started to carve out her own secret life. In high school she lied in order to see boys and go to dances. Her parents sensed all this, and in their minds they had already lost her. Nothing they said or did could keep her from becoming Americanized. When they telephoned her at Berkeley, all they heard was “Yeah Dad, yeah Mom, okay, yeah.”

In graduation photos, forced to stand with her parents, she looks positively gloomy.

Then the ultimate indignity: After college their daughter went to work for pennies as a producer for a new cable show, Q-TV, an issues and entertainment show for gays and lesbians. They knew their daughter wasn’t a lesbian, but if she had been that might have made more sense. Occasionally she showed up with videotapes, proud of her hard work, hoping to share.

Imagine this scene! Imagine what her parents were feeling. They left their homeland at middle age, their siblings sabotaged their attempt to assimilate, they both worked double shifts for fourteen years to put their daughter into one of the best colleges in America, and what did she do with this incredible opportunity? Not buy a house, not buy a new car, but rather—she created a great seven-minute segment on the hot new gay comic!

She had no steady boyfriend, no real income, but she’d gone to Palm Springs and sat by the pool for two days interviewing lesbian conventioneers about how, exactly, they practice safe sex!

And did she even get paid for this work? Not enough that she didn’t have to sell cigarettes to make her rent!

Oh, they were thrilled.

From the Hardcover edition.