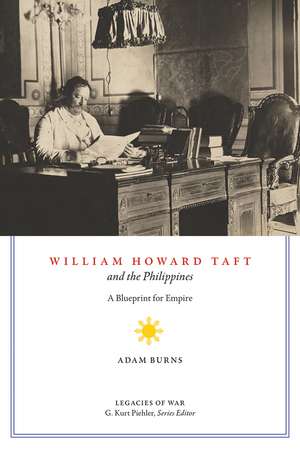

William Howard Taft and the Philippines: A Blueprint for Empire: Legacies of War

Autor Adam D. Burnsen Limba Engleză Hardback – 7 iul 2020

Adam D. Burns traces Taft’s course through six chapters, beginning with his years in the islands and then following it through his tenure as President Roosevelt’s secretary of war, his term as president of the United States, and his life after departing the White House. Across these years Taft continued his efforts to forge a lasting imperial bond and prevent Philippine independence.

Grounded in extensive primary source research, William Howard Taft and the Philippines is an engaging work that will interest scholars of Philippine history, American foreign policy, imperialism, the American presidency, the Progressive Era, and more.

Din seria Legacies of War

-

Preț: 352.42 lei

Preț: 352.42 lei -

Preț: 362.01 lei

Preț: 362.01 lei -

Preț: 461.77 lei

Preț: 461.77 lei -

Preț: 458.18 lei

Preț: 458.18 lei -

Preț: 261.73 lei

Preț: 261.73 lei -

Preț: 227.20 lei

Preț: 227.20 lei -

Preț: 133.80 lei

Preț: 133.80 lei -

Preț: 207.20 lei

Preț: 207.20 lei -

Preț: 407.07 lei

Preț: 407.07 lei -

Preț: 220.67 lei

Preț: 220.67 lei -

Preț: 176.68 lei

Preț: 176.68 lei -

Preț: 197.26 lei

Preț: 197.26 lei -

Preț: 251.36 lei

Preț: 251.36 lei -

Preț: 260.97 lei

Preț: 260.97 lei - 15%

Preț: 398.20 lei

Preț: 398.20 lei

Preț: 490.52 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 736

Preț estimativ în valută:

93.86€ • 98.01$ • 77.51£

93.86€ • 98.01$ • 77.51£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 15-29 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781621905691

ISBN-10: 1621905691

Pagini: 189

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: University of Tennessee Press

Colecția Univ Tennessee Press

Seria Legacies of War

ISBN-10: 1621905691

Pagini: 189

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: University of Tennessee Press

Colecția Univ Tennessee Press

Seria Legacies of War

Notă biografică

ADAM D. BURNS is a senior lecturer in history at the University of Wolverhampton. He holds a PhD from the University of Edinburgh and an EdD from the University of Leicester. He is the author of American Imperialism: The Territorial Expansion of the United States, 1783–2013 and recently contributed to the edited collection, The Continuing Imperialism of Free Trade: Developments, Trends, and the Role of Supranational Agents.

Extras

Early on in Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, the lead character, Charles Marlow, finds himself in Brussels at the start of what he hopes will be a journey of exploration. The Belgian capital, Marlow observes, is alive with talk of an overseas empire, and shortly thereafter he sets sail for this new imperial outpost. As Conrad’s tale continues, it becomes all too clear that the author believed imperialism had the potential to warp even the best intentions of those involved in such undertakings. When Conrad’s story was first published, the United States was still coming to terms with its own new overseas imperial possessions. On the back of victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States opted, among other things, to maintain control of the distant Philippine archipelago that had been under Spanish control for centuries. By 1899, the US was in the midst of another war, this time against those in the Philippines who were far from keen to see one imperial ruler leave and another arrive and take its place.

Conrad’s “whited sepulchre” of a city might just as well have described Washington, DC, around this time—a national capital abuzz with notions of the potential of this distant new imperial acquisition. In January 1900, Judge William Howard Taft was summoned to the capital by Pres. William McKinley. It turned out that Taft was about to begin his own imperial journey, and not so long afterward, he was aboard a vessel on course for the Philippines. For Taft, this journey was the start of an entirely different chapter in a life that had previously looked set on a very different trajectory indeed.

Taft was a figure plucked from an exceptionally promising judicial career and cast into the still-fluctuating aftermath of an unfinished war on the other side of the globe. He was not a career politician, diplomat, or soldier, and he was certainly not a man who fit the image of British imperialist exemplars of the time such as Evelyn Baring or Lord Curzon. Nevertheless, Taft became as determined to make a success of imperialism in the Philippines as his British contemporaries did in Egypt or India. He remained firmly committed to this duty far after the time it had fallen out of favor with the vast majority of his fellow politicians and compatriots, not to mention those in the Philippines. Taft’s resolve came not from a narrow concern about protecting his Philippine legacy, but from a sincere determination to make a success of US interventionism through generations of formal control—the very course the United States veered away from during the twentieth century.

Though some recent studies of Taft suggest that he was open—or even committed—to Philippine independence at some point in the future, this book suggests that it was Taft’s central mission to avoid that very end. This was partially for short-term expediency when pacifying the islands, but primarily with a view to building a long-term link that would last for generations to come. To explore the development and ultimate failure of Taft’s vision for a lasting and formal US imperial link with the Philippines is to see a blueprint drawn up, partially realized, and then abruptly abandoned. It is an account of a failed policy. Yet it is one that offers the opportunity to see the most far-advanced alternative to the short-term interventionism in populous territories outside of the Americas that has followed ever since.

The chapters that follow chart Taft’s course for just over two decades, from the time President McKinley summoned him to Washington to participate in the United States’ overseas experiment, to his appointment as chief justice of the United States by another president from Ohio, Warren G. Harding. The first half of the book focuses entirely on Taft’s time in the Philippines as a commissioner and the islands’ first civil governor between 1900 and 1903. Then the narrative follows Taft through his tenure as President Roosevelt’s secretary of war, his term as US president, and his life after leaving the White House. The work is organized thematically for the first part and chronologically for the second.49 This structure reflects the more immersive day-to-day impact of Taft’s influence on Philippine affairs prior to 1904, compared with the islands forming a significant part of his far wider responsibilities thereafter. Few see the Taft era in the Philippines as running only from 1900 to 1903, and most others believe it lasted until 1913 when Woodrow Wilson replaced him as president. However, it is argued here that Taft’s influence over the Philippine imperial debate only truly ended when his position on the US Supreme Court made it less seemly for him to remain involved in such a party political issue.

The first chapter begins by considering Taft’s orientation in the imperial debate at the turn of the century, and exploring how a skeptic of US territorial expansion overseas was sent to implement its realization. After all, when sent to the Philippines in 1900, Taft told both his political masters and the public in general, “I am not and never have been an expansionist. I have always hoped that the jurisdiction of our nation would not extend beyond territory between the two oceans. We have not solved all the problems of popular government so perfectly as to justify our voluntarily seeking more difficult ones abroad.” Yet Taft believed that, once involved, the United States had a duty to make the best of things. The chapter then outlines how Taft used a series of quite gestural and more practical sociocultural initiatives to “attract” the Filipino people to the benefits of US rule. This was to be the first of three major strands to his “policy of attraction,” which is somewhat roughly divided here into sociocultural, political, and economic realms.52 In the first of these arenas, Taft sought to show how US rule would differ from that of the Spanish whom the Americans had helped to displace, focusing instead on education, uplift, and even socialization between “races.” He promised a “Philippines for the Filipinos” even though his idea of what this amounted to was often very racialized.

The second chapter explores the political strand of the policy of attraction. Taft was clear from the outset that political reform, just like other changes, had to be visible to the people of the islands. To this end, Filipinos would have to be involved in running the islands. Taft advocated and brought about limited “Filipinization” that saw Filipinos appointed to the islands’ governing commission and plans drawn up for a popularly elected assembly. At the same time, however, Taft made it clear that American tutelage and Filipinization were not geared toward independence in the near future, or—in his ideal scenario—ever. To this end he suppressed those advocating independence from US rule and worked instead to empower existing elites. Though Taft clearly considered many of these figures venal spoilsmen of the type he loathed, he put his reservations aside in order to assure that he had the uninterrupted time and space to win over the islands’ population. Taft did not see this action as contrary to the policy of attraction, but rather as a vital part of it. He feared that, were the quest for independence the official direction of travel, any efforts at “attraction” or “winning hearts and minds” would be fundamentally undermined.

The final strand of Taft’s policy of attraction, its economic dimension, is explored in chapter 3. Taft believed that doubters in both the United States and the Philippines might become more sympathetic toward US imperialism if it could be seen to bring mutual financial dividends. Abolition or significant reduction of tariffs was to be key to this economic plan, as was an increase in inward investment from big businesses in the United States. From Taft’s point of view, the only sticking points were ensuring that this policy neither too much resembled the economic exploitation that so many American anti-imperialists warned of, nor seemed to herald a future of economic dependency that some in the Philippines feared. This chapter also considers Taft’s efforts to alter US immigration policy as it related to the islands (rather than to the United States). In this realm, however, his advocacy of continued immigration of Chinese workers met with even stronger resistance in both the US and the Philippines. On the economic front, where Taft thought he might gain the best proof of imperialism’s benefits, he met the sternest opposition.

The fourth chapter moves on from Taft’s tenure as civil governor of the Philippines and traces his continued attention to Philippine affairs through his time in President Roosevelt’s cabinet as secretary of war. In this position, Taft widened his duties markedly and assumed a more senior role in overseeing Philippine policy. He made two trips to the islands during this time, but on both occasions he sensed that the benefits of the US presence there were coming under increased scrutiny back in Washington. One of the primary drivers of this turn in political opinion was President Roosevelt’s increasing concern about Japan’s rise as a military power. This worry, in tandem with growing anti-Japanese sentiment in California and reciprocal opprobrium from the Japanese government, led many to fear a confrontation between the two nations in the most obvious geographical venue—the Philippines. Thus, during Taft’s trips to East Asia in 1905 and 1907, he faced the challenge not only of keeping things on track in the Philippines, but also of assuaging diplomatic tensions with Japan. Indeed, during Taft’s time at the War Department it became increasingly clear he would press to maintain the imperial relationship with the Philippines in the face of growing opposition. Taft stuck stubbornly to his imperial vision even when it amounted to opposing the wishes of the president himself.

Chapter 5 begins in 1908, with Taft well on course to take the highest office in the land for himself and secure his imperial plans for another four years. When Taft was elected that November, it was clear to all that his victory was a victory for Philippine retention, even if the issue was not a defining one for the campaign. He could not have made this idea clearer during the previous eight years. At the White House, the scope of Taft’s responsibilities increased significantly, and the time he was able to give to the Philippines became ever more pressured. However, for the first time he could also assume relatively safely that there was less threat of any radical change of policy, at least while he remained in office.

Despite various other pressing concerns and disappointments during his presidency, Taft achieved one significant step forward for his goals in the Philippines. This came with the eventual success of Philippine tariff reduction that he had campaigned for wholeheartedly over the past several years, even though the wider tariff legislation passed early on in his presidency met with an almost universal chorus of disenchantment. After the Republicans lost control of the US House of Representatives in the 1910 midterm elections, the issue of Philippine independence, by now a staple of Democratic opposition to the Republicans, began to gather pace. Taft kept such challenges at bay for the remainder of his time in office, but he clearly feared what might follow if he left the White House. When he was soundly beaten in the four-way presidential election of 1912, Taft vowed to fight on during his final “lame-duck” months in order to defend his dream of a lasting imperial bond.

The final chapter explores Taft’s postpresidential years, particularly the years from 1913 to 1916, which came to be dominated by his continued efforts to frustrate legislation that might promise future Philippine independence. Usually referred to as the “Jones Bill,” this legislation had first arisen during the final months of Taft’s presidency. He believed the measure would result in a “policy of scuttle” leaving the Philippines chaotic and vulnerable, not strong and independent.54 During these years, Taft was retired from his former political life and spending more time teaching law at his alma mater, Yale. Even so, he became a figurehead for those interest groups keen to maintain imperial control over the Philippines.

Taft spoke widely in opposition to the Jones Bill and tried to rally these networks and his erstwhile political allies to block its passage despite the unlikelihood of success. Nevertheless, in 1916, Taft was finally beaten, and the Jones Act secured what he had always said would be the step fatal to his dream of a future US “Dominion”: a promise of future independence. From this point on, Taft lamented, it would be nigh on impossible to ever retract this promise as the ultimate goal of US policy. In subsequent years, before his appointment to the Supreme Court, Taft continued to criticize Democratic policy toward the islands and Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s rhetoric of self-determination for colonial populations across the globe. Nevertheless, Taft knew that his plans had been irreparably undone by the Jones Act.

When Taft took his seat on the US Supreme Court in 1921 he could do so with some confidence that independence, even if virtually inevitable by this point, might well be increasingly distant. The Harding administration’s wholesale changes to the Democrats’ Philippine policy looked almost like a return to Taft-era normalcy. However, as Taft had predicted, when it came to the issue of promising future independence, once the genie was out of the bottle it could not be put back in. The Republican administrations of the 1920s might have slowed and even begun to reverse Democratic moves toward rapid self-government and independence. Yet within a few years of Taft’s death in 1930, Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic administration had drawn up a clear timetable for the islands’ independence. In 1946 the Philippines gained independence, the very thing Wilson had promised thirty years earlier and Taft had spent the best part of two decades prior to that trying to prevent. Taft’s blueprint for a lasting British-style Dominion for the United States in the Philippines had ultimately come to naught.

Conrad’s “whited sepulchre” of a city might just as well have described Washington, DC, around this time—a national capital abuzz with notions of the potential of this distant new imperial acquisition. In January 1900, Judge William Howard Taft was summoned to the capital by Pres. William McKinley. It turned out that Taft was about to begin his own imperial journey, and not so long afterward, he was aboard a vessel on course for the Philippines. For Taft, this journey was the start of an entirely different chapter in a life that had previously looked set on a very different trajectory indeed.

Taft was a figure plucked from an exceptionally promising judicial career and cast into the still-fluctuating aftermath of an unfinished war on the other side of the globe. He was not a career politician, diplomat, or soldier, and he was certainly not a man who fit the image of British imperialist exemplars of the time such as Evelyn Baring or Lord Curzon. Nevertheless, Taft became as determined to make a success of imperialism in the Philippines as his British contemporaries did in Egypt or India. He remained firmly committed to this duty far after the time it had fallen out of favor with the vast majority of his fellow politicians and compatriots, not to mention those in the Philippines. Taft’s resolve came not from a narrow concern about protecting his Philippine legacy, but from a sincere determination to make a success of US interventionism through generations of formal control—the very course the United States veered away from during the twentieth century.

Though some recent studies of Taft suggest that he was open—or even committed—to Philippine independence at some point in the future, this book suggests that it was Taft’s central mission to avoid that very end. This was partially for short-term expediency when pacifying the islands, but primarily with a view to building a long-term link that would last for generations to come. To explore the development and ultimate failure of Taft’s vision for a lasting and formal US imperial link with the Philippines is to see a blueprint drawn up, partially realized, and then abruptly abandoned. It is an account of a failed policy. Yet it is one that offers the opportunity to see the most far-advanced alternative to the short-term interventionism in populous territories outside of the Americas that has followed ever since.

The chapters that follow chart Taft’s course for just over two decades, from the time President McKinley summoned him to Washington to participate in the United States’ overseas experiment, to his appointment as chief justice of the United States by another president from Ohio, Warren G. Harding. The first half of the book focuses entirely on Taft’s time in the Philippines as a commissioner and the islands’ first civil governor between 1900 and 1903. Then the narrative follows Taft through his tenure as President Roosevelt’s secretary of war, his term as US president, and his life after leaving the White House. The work is organized thematically for the first part and chronologically for the second.49 This structure reflects the more immersive day-to-day impact of Taft’s influence on Philippine affairs prior to 1904, compared with the islands forming a significant part of his far wider responsibilities thereafter. Few see the Taft era in the Philippines as running only from 1900 to 1903, and most others believe it lasted until 1913 when Woodrow Wilson replaced him as president. However, it is argued here that Taft’s influence over the Philippine imperial debate only truly ended when his position on the US Supreme Court made it less seemly for him to remain involved in such a party political issue.

The first chapter begins by considering Taft’s orientation in the imperial debate at the turn of the century, and exploring how a skeptic of US territorial expansion overseas was sent to implement its realization. After all, when sent to the Philippines in 1900, Taft told both his political masters and the public in general, “I am not and never have been an expansionist. I have always hoped that the jurisdiction of our nation would not extend beyond territory between the two oceans. We have not solved all the problems of popular government so perfectly as to justify our voluntarily seeking more difficult ones abroad.” Yet Taft believed that, once involved, the United States had a duty to make the best of things. The chapter then outlines how Taft used a series of quite gestural and more practical sociocultural initiatives to “attract” the Filipino people to the benefits of US rule. This was to be the first of three major strands to his “policy of attraction,” which is somewhat roughly divided here into sociocultural, political, and economic realms.52 In the first of these arenas, Taft sought to show how US rule would differ from that of the Spanish whom the Americans had helped to displace, focusing instead on education, uplift, and even socialization between “races.” He promised a “Philippines for the Filipinos” even though his idea of what this amounted to was often very racialized.

The second chapter explores the political strand of the policy of attraction. Taft was clear from the outset that political reform, just like other changes, had to be visible to the people of the islands. To this end, Filipinos would have to be involved in running the islands. Taft advocated and brought about limited “Filipinization” that saw Filipinos appointed to the islands’ governing commission and plans drawn up for a popularly elected assembly. At the same time, however, Taft made it clear that American tutelage and Filipinization were not geared toward independence in the near future, or—in his ideal scenario—ever. To this end he suppressed those advocating independence from US rule and worked instead to empower existing elites. Though Taft clearly considered many of these figures venal spoilsmen of the type he loathed, he put his reservations aside in order to assure that he had the uninterrupted time and space to win over the islands’ population. Taft did not see this action as contrary to the policy of attraction, but rather as a vital part of it. He feared that, were the quest for independence the official direction of travel, any efforts at “attraction” or “winning hearts and minds” would be fundamentally undermined.

The final strand of Taft’s policy of attraction, its economic dimension, is explored in chapter 3. Taft believed that doubters in both the United States and the Philippines might become more sympathetic toward US imperialism if it could be seen to bring mutual financial dividends. Abolition or significant reduction of tariffs was to be key to this economic plan, as was an increase in inward investment from big businesses in the United States. From Taft’s point of view, the only sticking points were ensuring that this policy neither too much resembled the economic exploitation that so many American anti-imperialists warned of, nor seemed to herald a future of economic dependency that some in the Philippines feared. This chapter also considers Taft’s efforts to alter US immigration policy as it related to the islands (rather than to the United States). In this realm, however, his advocacy of continued immigration of Chinese workers met with even stronger resistance in both the US and the Philippines. On the economic front, where Taft thought he might gain the best proof of imperialism’s benefits, he met the sternest opposition.

The fourth chapter moves on from Taft’s tenure as civil governor of the Philippines and traces his continued attention to Philippine affairs through his time in President Roosevelt’s cabinet as secretary of war. In this position, Taft widened his duties markedly and assumed a more senior role in overseeing Philippine policy. He made two trips to the islands during this time, but on both occasions he sensed that the benefits of the US presence there were coming under increased scrutiny back in Washington. One of the primary drivers of this turn in political opinion was President Roosevelt’s increasing concern about Japan’s rise as a military power. This worry, in tandem with growing anti-Japanese sentiment in California and reciprocal opprobrium from the Japanese government, led many to fear a confrontation between the two nations in the most obvious geographical venue—the Philippines. Thus, during Taft’s trips to East Asia in 1905 and 1907, he faced the challenge not only of keeping things on track in the Philippines, but also of assuaging diplomatic tensions with Japan. Indeed, during Taft’s time at the War Department it became increasingly clear he would press to maintain the imperial relationship with the Philippines in the face of growing opposition. Taft stuck stubbornly to his imperial vision even when it amounted to opposing the wishes of the president himself.

Chapter 5 begins in 1908, with Taft well on course to take the highest office in the land for himself and secure his imperial plans for another four years. When Taft was elected that November, it was clear to all that his victory was a victory for Philippine retention, even if the issue was not a defining one for the campaign. He could not have made this idea clearer during the previous eight years. At the White House, the scope of Taft’s responsibilities increased significantly, and the time he was able to give to the Philippines became ever more pressured. However, for the first time he could also assume relatively safely that there was less threat of any radical change of policy, at least while he remained in office.

Despite various other pressing concerns and disappointments during his presidency, Taft achieved one significant step forward for his goals in the Philippines. This came with the eventual success of Philippine tariff reduction that he had campaigned for wholeheartedly over the past several years, even though the wider tariff legislation passed early on in his presidency met with an almost universal chorus of disenchantment. After the Republicans lost control of the US House of Representatives in the 1910 midterm elections, the issue of Philippine independence, by now a staple of Democratic opposition to the Republicans, began to gather pace. Taft kept such challenges at bay for the remainder of his time in office, but he clearly feared what might follow if he left the White House. When he was soundly beaten in the four-way presidential election of 1912, Taft vowed to fight on during his final “lame-duck” months in order to defend his dream of a lasting imperial bond.

The final chapter explores Taft’s postpresidential years, particularly the years from 1913 to 1916, which came to be dominated by his continued efforts to frustrate legislation that might promise future Philippine independence. Usually referred to as the “Jones Bill,” this legislation had first arisen during the final months of Taft’s presidency. He believed the measure would result in a “policy of scuttle” leaving the Philippines chaotic and vulnerable, not strong and independent.54 During these years, Taft was retired from his former political life and spending more time teaching law at his alma mater, Yale. Even so, he became a figurehead for those interest groups keen to maintain imperial control over the Philippines.

Taft spoke widely in opposition to the Jones Bill and tried to rally these networks and his erstwhile political allies to block its passage despite the unlikelihood of success. Nevertheless, in 1916, Taft was finally beaten, and the Jones Act secured what he had always said would be the step fatal to his dream of a future US “Dominion”: a promise of future independence. From this point on, Taft lamented, it would be nigh on impossible to ever retract this promise as the ultimate goal of US policy. In subsequent years, before his appointment to the Supreme Court, Taft continued to criticize Democratic policy toward the islands and Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s rhetoric of self-determination for colonial populations across the globe. Nevertheless, Taft knew that his plans had been irreparably undone by the Jones Act.

When Taft took his seat on the US Supreme Court in 1921 he could do so with some confidence that independence, even if virtually inevitable by this point, might well be increasingly distant. The Harding administration’s wholesale changes to the Democrats’ Philippine policy looked almost like a return to Taft-era normalcy. However, as Taft had predicted, when it came to the issue of promising future independence, once the genie was out of the bottle it could not be put back in. The Republican administrations of the 1920s might have slowed and even begun to reverse Democratic moves toward rapid self-government and independence. Yet within a few years of Taft’s death in 1930, Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic administration had drawn up a clear timetable for the islands’ independence. In 1946 the Philippines gained independence, the very thing Wilson had promised thirty years earlier and Taft had spent the best part of two decades prior to that trying to prevent. Taft’s blueprint for a lasting British-style Dominion for the United States in the Philippines had ultimately come to naught.

Recenzii

“This concise book examines the political career of William Howard Taft based around one issue: his support for continued U.S. rule in the Philippines…. Anyone looking to understand the thinking of a leading figure in the early history of U.S. overseas empire would benefit from reading Burns’s portrait of Taft’s imperial career.”—Journal of Arizona History “The book… benefits from exhaustive research and sound conclusions. Moreover, it is a valuable addition to the literature on one of the most under-appreciated presidents of our history”—Presidential Studies Quarterly

“Burns has written a commendable book. It is briskly written, sensibly argued, and well researched in the existing literature as well as in newspapers, public documents, and manuscript collections at the Library of Congress… the book demonstrates that Taft was both a serious actor on Philippine matters and a politician of great determination and modest skill. William Howard Taft and the Philippines provides a valuable perspective on an important chapter of a consequential life."—Ohio History

“Burns has written a commendable book. It is briskly written, sensibly argued, and well researched in the existing literature as well as in newspapers, public documents, and manuscript collections at the Library of Congress… the book demonstrates that Taft was both a serious actor on Philippine matters and a politician of great determination and modest skill. William Howard Taft and the Philippines provides a valuable perspective on an important chapter of a consequential life."—Ohio History