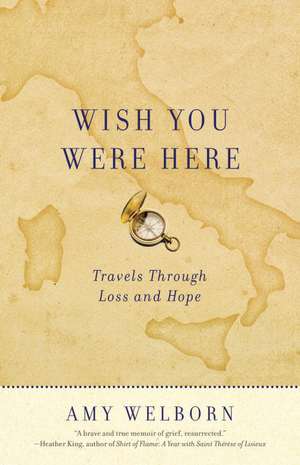

Wish You Were Here: Travels Through Loss and Hope

Autor Amy Welbornen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2012

Along the narrow roads and hairpin turns, the narrative reveals the beauty of the ordinary and the commonplace and asks stark questions about how we fill the empty places that a loved one leaves behind. It is a meditation on the possibility of faith, one that is unflinching, uncompromising, and altogether unsentimental when confronted by the ultimate test of belief. This book is not only a well-told memoir, but a testimony to the truth that love is stronger than death.

Preț: 99.30 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 149

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.00€ • 20.32$ • 15.84£

19.00€ • 20.32$ • 15.84£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-11 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307716385

ISBN-10: 0307716384

Pagini: 245

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: IMAGE

ISBN-10: 0307716384

Pagini: 245

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: IMAGE

Notă biografică

AMY WELBORN has written for Our Sunday Visitor, Catholic News Service, Beliefnet, the New York Times, and Commonweal. She has five children and lives in Birmingham, Alabama.

Extras

Introduction

I raced into the backyard just after midnight.

Barefoot, in pajamas, I raised an empty brown pill bottle into the frigid Kansas darkness, swept it through the air, snapped the white disc of a lid on top, and then rushed back into the silent house, through the hall into my room, wrote on a slip of paper, and taped it to the bottle.

Air—the label said— from 1970.

The bottle still rattles around in a drawer in my father’s house, I think. I wouldn’t throw it away if I ran across it. I wouldn’t open it either. I don’t know why. After all, it’s only air.

***

Here’s what I remember from the first days of a February years later.

Sunday morning, we arrived at Mass at Our Lady of Sorrows parish so late that the only seats left were in the balcony. The first scripture reading was already happening by the time the fi ve of us squeezed into the pew: me; my husband, Mike; our two little boys, Joseph and Michael; and Katie, my teenaged daughter from my first marriage.

The elderly pastor—elfin in appearance, but resonant and dramatic in tone, always ending his sentences with a forceful, downward emphasis as if his words were screws he was forcing into a particularly tough board—began to preach from the sanctuary below us. In the Gospel that morning, Jesus had exorcised demons, but this would not be Monsignor’s subject. That would be death, of course.

Mike and I glanced at each other, amused. For in the fi ve months we had attended Mass in the parish in our new city of Birmingham, Alabama, we’d noticed this about the pastor: he liked to talk about death. No matter what the Gospel or the feast, it seemed, he’d find his way to it: we are all going to die and there is no more important task than preparing for the certainty. No surprise, really. The man had spent his adult life ministering to the dying and the grieving, and he was in his late seventies himself. Death might be on his mind.

***

So that morning, nodding only briefly to Jesus and the demons, Monsignor moved on to a book he’d been given about life- after-death experiences, and here we were again at death’s door, where he would talk to us about death and—always his most repeated point—being prepared for it.

So yes, I remember glancing at Mike and him glancing back and I remember sharing knowing, slight smiles at death’s introduction. And we settled back to listen, to pray, to think about work tomorrow, about the next book or article deadline, all of us up there in the balcony, an enormous bas-relief of that Lady of Sorrows cradling her dead son on the sanctuary wall behind the altar straight ahead of us, in plain view.

I remember Mike kneeling beside me after Communion. I remember because his posture was just a little different than normal. He usually looked ahead, or down at a misbehaving son, or just rested his chin on his folded hands. That morning, I remember, he knelt there, his face buried in his hands.

I remember that we went to Whole Foods after Mass and the boys picked out muffins and Katie got a croissant and Mike wandered off to look for something and he came back with a bag of loose tea because that was his latest thing. He said this was part of his renewed project of getting back into shape, a project interrupted by our move and the substantial pressures of his new job as director of evangelization (and the Pro-Life Office . . . and the Family Life Office . . . and the Campus Ministry Office . . . and the Child Protection Office . . . he seemed to add a job every month we’d lived there) for the diocese. Mike was a man of routines, and this transition had messed with his running and lifting schedule in a big way. He wasn’t in the worst shape he’d ever been but neither was he in the best, so in this new year, he’d get back on track.

For some reason, the tea would evidently be a part of that. I remember him walking down the aisle, cradling boxes of tea and a box of filters in his arms. The tea was green, because cutting down on caffeine would be part of the renewed health regime too.

And I remember him wrapping his arms around me at the Botanical Gardens a few hours later.

It was February, and although a few weeks later it would snow, that day it was mild enough for a walk in and through the various, quite diverse areas of that beautiful public space: the Japanese garden, hills rich with ferns, the greenhouse desert—all of us except Katie, who stayed back at the apartment, swamped with homework.

I remember how when we had arrived and I was getting ready to close up and lock the car, I held my camera in my hand and debated whether I should bring it along or not.

I looked around at the still mostly dead, not quite budding vegetation. I considered the boys and Mike waiting for me near the fountain at the entrance. No, I decided. There will be another time—later, when there’s more in bloom and more color. We’ll all come back then and there will be more pictures.

Yes, I remember how Mike grabbed me and hugged me in the middle of the Alabama Woodlands, boys tramping through the dry brown leaves thick across the ground around us. I remember how happy we were—ecstatic, even— to be back in the South, to never have to endure another northern Indiana winter, those months of backbreaking snow that just seemed to go on and on. Not here. Very soon, the dogwoods would be budding, the pink and violet azaleas would be blossoming, and we would return to walk in the gardens again, to see the colors, to relax in the certainty of new life gently but surely overwhelming the old. It would all happen, we were certain: another walk, another spring. Years of them, stretching ahead.

I remember the next evening, which was February 2, the Feast of the Presentation, a celebration of the day Joseph and Mary took the baby Jesus to the Temple forty days after his birth as a symbolic offering of their child to God. I decided we would do a special prayer before dinner, so I printed out a very condensed version of Night Prayer: the last of the daily prayers in the Liturgy of the Hours. Now, that Night Prayer, or Compline, always includes a prayer called the Nunc Dimittis, words taken directly from the Gospel of Luke. An elderly man named Simeon met the Holy Family at the Temple that day and thanked God in words very appropriate for those minutes before we release ourselves to sleep:

Now, Master, you may let your servant go in peace, according to your word, for my eyes have seen your salvation, which you prepared in sight of all the peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and glory for your people Israel.

Those of us who could read, recited it aloud; those of us who couldn’t, fidgeted. Mike knew it by heart because he prayed these prayers every day himself, and had almost his whole adult life, as a seminarian, as a Catholic priest, and after leaving active priestly ministry in 1993, as a layman working in education and Catholic publishing. He never stopped praying those prayers. I remember that deep voice. I can hear it now.

Lord, now you may let your servant go in peace . . .

I remember him sitting on the couch after dinner, laughing at a sitcom. I remember him raising himself grudgingly from that couch to head trudging, so tired, into our room, where his computer waited for him, and where he needed to fi nish up his column for the diocesan newspaper, due tomorrow. He had been so tired so early in the evenings for the past couple of months, so tired so early at night, it sometimes seemed as if he wouldn’t make it down that short hall from the living room to the bedroom. But, he had been saying, getting into shape would take care of it. He would get his energy back.

Still thinking about that column, he posted on Facebook in the early evening. Eventually, he got it done, that column. He wrote things in it like, “None of us knows what the future holds,” and, quoting his friend Fr. Benedict Groeschel, “We have no plans except to be led by God.”

That’s what the man wrote.

I remember.

If I could put it all in a bottle, snap the lid on tight, and keep it forever, I would. But this— this is the best I can do.

***

The next afternoon—it was a Tuesday—I slumped against the cool tiled wall of a hospital emergency room, looking at him for the first time since he and Joseph had left the apartment earlier that morning.

He was covered with a light blue sheet up to his bare shoulders; he looked as if he were dozing on the table on the other side of the room.

But he was dead.

He had been dead all day, and I didn’t even know it.

***

They had left the apartment that morning, he and seven-year- old Joseph, just as they always did, around 7:30. He’d dropped Joseph off at school, then driven directly to the YMCA down the road. He’d just started going there; they didn’t know him at the front desk yet, couldn’t tell you who he was. He went to the locker room, changed his clothes, stepped on a treadmill, and started to run.

After about ten minutes, he raised the speed. I know this because the woman running next to him noticed, impressed because he was holding that quicker pace.

Then he dropped to the floor, hard. She was a dentist and had CPR training, so she knew what to do and what to look for. “His eyes were open,” she told me kindly but bluntly over the phone two weeks later, “but there was nothing there.”

I was grateful to her. But I was also jealous. Resentful, even. She’d been with him when my husband, my best friend, drew his last breath.

Not me.

So what was I doing while my husband died? Mundane things, the things I did most every day. I had basically spent the morning blogging about churchy matters, throwing some laundry into the wash, reading to four-year- old Michael, and being irritated about the inevitability of dinner. I was at a point of great frustration with everyone’s varied culinary and dietary needs and desires—a daughter convinced she was fat but who wouldn’t eat fresh vegetables, a husband who only wanted to eat fresh vegetables, and two little boys who really wouldn’t eat anything that didn’t lie on the color spectrum from beige to brown. Yes, having to deal with dinner for this picky crowd struck me as a big problem, an obstacle to my complete happiness.

The phone call came at one, just as Michael had gone for his nap on his lower bunk in the boys’ room. The caller ID screen on the phone in the kitchen identified the source of the call as a local hospital, and I almost didn’t answer it, assuming it was a wrong number. But I did and I listened in growing confusion as the woman on the other end asked if my name was Amy. After I said yes, she told me that there was someone named Mike at the hospital there who was associated with someone named Amy and they wondered if I was the Amy in question so would I please come down so they could check it out. Seriously. That was all I could get out of the woman except the advice to leave my young child at home. They wouldn’t even answer my direct questions. “Is it ‘Dubruiel’? Is he alive?”

“Please just come down. Ask for Lee. Do you know where to park?”

So over the course of a hideous forty-five minutes, I put Michael in the car, trying not to wake him, drove to Katie’s school, got her out of class, and drove back to the apartment, where she would stay with him. On the drive, I whispered a report of the phone call, telling her and telling myself that even if something had happened to Mike, he was probably still alive. Surely. We told ourselves that. But even as I assured her, I was shaking, inside and out.

On the way downtown by myself, I prayed and cried hard. I banged the steering wheel and shook it; I told myself, He’s alive, he’s alive, he’s alive . . . I tried to tell God— I shouted at God— to make sure he remembered, we just moved here . . . he’s only fifty . . . two little boys . . .

. . . he’s alive, he’s alive.

Please.

***

It’s late June now, almost five months after that day, and the four of us, Katie, the two little boys, and I—without a drop of Italian blood between us—are hauling suitcases over cobblestones in a tiny little town in the north of Sicily. We make a ridiculous, embarrassing amount of noise as we bump our way through a small plaza past a small fountain, headed to one of the three streets in this tiny, quiet village.

I had parked the compact white rental car in the lot outside the village, only understanding later, in retrospect, what the elderly lot attendant had been trying to tell me, in his mix of Italian and English— that although cars were prohibited in the village, generally, it would be perfectly all right for me to pull up to the door of the B and B and unload.

But I didn’t understand, and I see him shake his head at us as we walk away, clattering. Except for all our commotion, the street—which seems to be the only real street in the village—is empty. We pass a large stone fountain in the middle of the tiny square, pouring out fresh acqua from its spout. We keep walking, suitcase wheels taking a beating, past a vending machine that sells contact lenses, past the parish church, past white plastic tables and chairs in a shaded courtyard, and finally arrive at the pensione where we would spend the next few days of summer.

Just down the hill, a half mile away, the Mediterranean glistened, a brilliant blue. We drove along it on our way here from the Palermo airport, and we would step into its waters several times over the next two weeks to let ourselves be cooled by the sea. We would wade in it and plunge into it here in the north, and a week later, far on the other side, the southern coast of Sicily. In between, we would see ruins and castles, we’d get lost, eat gelato, light candles in dark churches, and pray under stars. And every moment of it, I would look for him.

It was like that every day at home, anyway, so why not? Why not take that daily routine of remembering and searching, of excavation of life and death, those memories of my husband laughing, of his body cooling under a blue sheet, that constant deep, frantic prayer for his little boys, why not take the cross and the empty tomb, weeping mothers and wounds probed by a doubter—why not take it all out of a beige- colored third-floor apartment in an Alabama summer, heavy with humidity, memories, and landmarks, why not wrest the top off the bottle of the past and spill it out here?

In the pictures in the guidebooks to Sicily, all I saw was the past, remnants of what was dead and gone. It seemed right. Maybe here in Sicily, picking my way on worn- down paths around tumbling ancient walls and broken columns, I will catch a clue as to how to live with it all. And because here the veil between past and present seems as thin as the cooling breeze from the sea, maybe, just once in a while, it will whip aside, it will lift, and I’ll see.

***

This book is about how we got from here to there, from February to June, from Alabama to Sicily, and why. It’s not my autobiography or his biography or a portrait of our marriage. It’s not a theological treatise on the Last Things—far from it—or a guide on how to live with grief. It’s a memoir of what we—mostly I—went through, thought, prayed, and did during a trip to Sicily, a place I had never once before thought about going in forty-nine years of life, a trip I impulsively planned about a month after my husband died of a heart attack.

I wrote it because, as a longtime book, column, and blog writer about matters of faith and life, I could not avoid writing about grief and loss and faith in the months after Mike’s death. I did wait, though. I hesitated every time before tapping the “publish” button on my blog because I didn’t want to be seen as seeking sympathy or exploiting it. Exploiting him.

But then every time I would go ahead and post a blog entry related to grief, readers’ reactions—as they thanked me and, most helpfully, shared their own experiences—convinced me it might be all right.

There was something else, too.

People kept dying. They just wouldn’t stop.

The mother of one of my daughter’s classmates, a woman younger than I am, dropped dead of an aneurysm. Two weeks later, another classmate of Katie’s died in a car accident.

An online friend of mine, a fellow writer nicknamed the “Internet Monk,” Michael Spencer, was diagnosed with cancer in the late fall and died the day after Easter, aged fi fty-two.

The fall after Mike died, in fact, eight months to the day, on October 3, my good friend Molly, who lived in Florida, died. She had taught my children, I hers, and she had been battling various forms of cancer for years. That evening, one of her daughters wrote, she “went peacefully home.”

If we are Christians, we have two kinds of hope constantly held out to us: the hope that the cross gives, that our sins have no more power over us, that in our suffering we are not alone, that God knows, that God suffers, mysteriously with us; and the hope of the empty tomb, that death has no more power over us either, that Jesus Christ lives.

But still, in the midst of the hope, the pietà remains. There is Our Lady of Sorrows, there is the mother standing at the cross, weeping, there are the friends, uncomprehending and regretful, there is a suddenly empty space and strange silence, there are the doubters scoffing from afar, challenging, Where is your hope now?

So we went to Sicily, to see.

I raced into the backyard just after midnight.

Barefoot, in pajamas, I raised an empty brown pill bottle into the frigid Kansas darkness, swept it through the air, snapped the white disc of a lid on top, and then rushed back into the silent house, through the hall into my room, wrote on a slip of paper, and taped it to the bottle.

Air—the label said— from 1970.

The bottle still rattles around in a drawer in my father’s house, I think. I wouldn’t throw it away if I ran across it. I wouldn’t open it either. I don’t know why. After all, it’s only air.

***

Here’s what I remember from the first days of a February years later.

Sunday morning, we arrived at Mass at Our Lady of Sorrows parish so late that the only seats left were in the balcony. The first scripture reading was already happening by the time the fi ve of us squeezed into the pew: me; my husband, Mike; our two little boys, Joseph and Michael; and Katie, my teenaged daughter from my first marriage.

The elderly pastor—elfin in appearance, but resonant and dramatic in tone, always ending his sentences with a forceful, downward emphasis as if his words were screws he was forcing into a particularly tough board—began to preach from the sanctuary below us. In the Gospel that morning, Jesus had exorcised demons, but this would not be Monsignor’s subject. That would be death, of course.

Mike and I glanced at each other, amused. For in the fi ve months we had attended Mass in the parish in our new city of Birmingham, Alabama, we’d noticed this about the pastor: he liked to talk about death. No matter what the Gospel or the feast, it seemed, he’d find his way to it: we are all going to die and there is no more important task than preparing for the certainty. No surprise, really. The man had spent his adult life ministering to the dying and the grieving, and he was in his late seventies himself. Death might be on his mind.

***

So that morning, nodding only briefly to Jesus and the demons, Monsignor moved on to a book he’d been given about life- after-death experiences, and here we were again at death’s door, where he would talk to us about death and—always his most repeated point—being prepared for it.

So yes, I remember glancing at Mike and him glancing back and I remember sharing knowing, slight smiles at death’s introduction. And we settled back to listen, to pray, to think about work tomorrow, about the next book or article deadline, all of us up there in the balcony, an enormous bas-relief of that Lady of Sorrows cradling her dead son on the sanctuary wall behind the altar straight ahead of us, in plain view.

I remember Mike kneeling beside me after Communion. I remember because his posture was just a little different than normal. He usually looked ahead, or down at a misbehaving son, or just rested his chin on his folded hands. That morning, I remember, he knelt there, his face buried in his hands.

I remember that we went to Whole Foods after Mass and the boys picked out muffins and Katie got a croissant and Mike wandered off to look for something and he came back with a bag of loose tea because that was his latest thing. He said this was part of his renewed project of getting back into shape, a project interrupted by our move and the substantial pressures of his new job as director of evangelization (and the Pro-Life Office . . . and the Family Life Office . . . and the Campus Ministry Office . . . and the Child Protection Office . . . he seemed to add a job every month we’d lived there) for the diocese. Mike was a man of routines, and this transition had messed with his running and lifting schedule in a big way. He wasn’t in the worst shape he’d ever been but neither was he in the best, so in this new year, he’d get back on track.

For some reason, the tea would evidently be a part of that. I remember him walking down the aisle, cradling boxes of tea and a box of filters in his arms. The tea was green, because cutting down on caffeine would be part of the renewed health regime too.

And I remember him wrapping his arms around me at the Botanical Gardens a few hours later.

It was February, and although a few weeks later it would snow, that day it was mild enough for a walk in and through the various, quite diverse areas of that beautiful public space: the Japanese garden, hills rich with ferns, the greenhouse desert—all of us except Katie, who stayed back at the apartment, swamped with homework.

I remember how when we had arrived and I was getting ready to close up and lock the car, I held my camera in my hand and debated whether I should bring it along or not.

I looked around at the still mostly dead, not quite budding vegetation. I considered the boys and Mike waiting for me near the fountain at the entrance. No, I decided. There will be another time—later, when there’s more in bloom and more color. We’ll all come back then and there will be more pictures.

Yes, I remember how Mike grabbed me and hugged me in the middle of the Alabama Woodlands, boys tramping through the dry brown leaves thick across the ground around us. I remember how happy we were—ecstatic, even— to be back in the South, to never have to endure another northern Indiana winter, those months of backbreaking snow that just seemed to go on and on. Not here. Very soon, the dogwoods would be budding, the pink and violet azaleas would be blossoming, and we would return to walk in the gardens again, to see the colors, to relax in the certainty of new life gently but surely overwhelming the old. It would all happen, we were certain: another walk, another spring. Years of them, stretching ahead.

I remember the next evening, which was February 2, the Feast of the Presentation, a celebration of the day Joseph and Mary took the baby Jesus to the Temple forty days after his birth as a symbolic offering of their child to God. I decided we would do a special prayer before dinner, so I printed out a very condensed version of Night Prayer: the last of the daily prayers in the Liturgy of the Hours. Now, that Night Prayer, or Compline, always includes a prayer called the Nunc Dimittis, words taken directly from the Gospel of Luke. An elderly man named Simeon met the Holy Family at the Temple that day and thanked God in words very appropriate for those minutes before we release ourselves to sleep:

Now, Master, you may let your servant go in peace, according to your word, for my eyes have seen your salvation, which you prepared in sight of all the peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and glory for your people Israel.

Those of us who could read, recited it aloud; those of us who couldn’t, fidgeted. Mike knew it by heart because he prayed these prayers every day himself, and had almost his whole adult life, as a seminarian, as a Catholic priest, and after leaving active priestly ministry in 1993, as a layman working in education and Catholic publishing. He never stopped praying those prayers. I remember that deep voice. I can hear it now.

Lord, now you may let your servant go in peace . . .

I remember him sitting on the couch after dinner, laughing at a sitcom. I remember him raising himself grudgingly from that couch to head trudging, so tired, into our room, where his computer waited for him, and where he needed to fi nish up his column for the diocesan newspaper, due tomorrow. He had been so tired so early in the evenings for the past couple of months, so tired so early at night, it sometimes seemed as if he wouldn’t make it down that short hall from the living room to the bedroom. But, he had been saying, getting into shape would take care of it. He would get his energy back.

Still thinking about that column, he posted on Facebook in the early evening. Eventually, he got it done, that column. He wrote things in it like, “None of us knows what the future holds,” and, quoting his friend Fr. Benedict Groeschel, “We have no plans except to be led by God.”

That’s what the man wrote.

I remember.

If I could put it all in a bottle, snap the lid on tight, and keep it forever, I would. But this— this is the best I can do.

***

The next afternoon—it was a Tuesday—I slumped against the cool tiled wall of a hospital emergency room, looking at him for the first time since he and Joseph had left the apartment earlier that morning.

He was covered with a light blue sheet up to his bare shoulders; he looked as if he were dozing on the table on the other side of the room.

But he was dead.

He had been dead all day, and I didn’t even know it.

***

They had left the apartment that morning, he and seven-year- old Joseph, just as they always did, around 7:30. He’d dropped Joseph off at school, then driven directly to the YMCA down the road. He’d just started going there; they didn’t know him at the front desk yet, couldn’t tell you who he was. He went to the locker room, changed his clothes, stepped on a treadmill, and started to run.

After about ten minutes, he raised the speed. I know this because the woman running next to him noticed, impressed because he was holding that quicker pace.

Then he dropped to the floor, hard. She was a dentist and had CPR training, so she knew what to do and what to look for. “His eyes were open,” she told me kindly but bluntly over the phone two weeks later, “but there was nothing there.”

I was grateful to her. But I was also jealous. Resentful, even. She’d been with him when my husband, my best friend, drew his last breath.

Not me.

So what was I doing while my husband died? Mundane things, the things I did most every day. I had basically spent the morning blogging about churchy matters, throwing some laundry into the wash, reading to four-year- old Michael, and being irritated about the inevitability of dinner. I was at a point of great frustration with everyone’s varied culinary and dietary needs and desires—a daughter convinced she was fat but who wouldn’t eat fresh vegetables, a husband who only wanted to eat fresh vegetables, and two little boys who really wouldn’t eat anything that didn’t lie on the color spectrum from beige to brown. Yes, having to deal with dinner for this picky crowd struck me as a big problem, an obstacle to my complete happiness.

The phone call came at one, just as Michael had gone for his nap on his lower bunk in the boys’ room. The caller ID screen on the phone in the kitchen identified the source of the call as a local hospital, and I almost didn’t answer it, assuming it was a wrong number. But I did and I listened in growing confusion as the woman on the other end asked if my name was Amy. After I said yes, she told me that there was someone named Mike at the hospital there who was associated with someone named Amy and they wondered if I was the Amy in question so would I please come down so they could check it out. Seriously. That was all I could get out of the woman except the advice to leave my young child at home. They wouldn’t even answer my direct questions. “Is it ‘Dubruiel’? Is he alive?”

“Please just come down. Ask for Lee. Do you know where to park?”

So over the course of a hideous forty-five minutes, I put Michael in the car, trying not to wake him, drove to Katie’s school, got her out of class, and drove back to the apartment, where she would stay with him. On the drive, I whispered a report of the phone call, telling her and telling myself that even if something had happened to Mike, he was probably still alive. Surely. We told ourselves that. But even as I assured her, I was shaking, inside and out.

On the way downtown by myself, I prayed and cried hard. I banged the steering wheel and shook it; I told myself, He’s alive, he’s alive, he’s alive . . . I tried to tell God— I shouted at God— to make sure he remembered, we just moved here . . . he’s only fifty . . . two little boys . . .

. . . he’s alive, he’s alive.

Please.

***

It’s late June now, almost five months after that day, and the four of us, Katie, the two little boys, and I—without a drop of Italian blood between us—are hauling suitcases over cobblestones in a tiny little town in the north of Sicily. We make a ridiculous, embarrassing amount of noise as we bump our way through a small plaza past a small fountain, headed to one of the three streets in this tiny, quiet village.

I had parked the compact white rental car in the lot outside the village, only understanding later, in retrospect, what the elderly lot attendant had been trying to tell me, in his mix of Italian and English— that although cars were prohibited in the village, generally, it would be perfectly all right for me to pull up to the door of the B and B and unload.

But I didn’t understand, and I see him shake his head at us as we walk away, clattering. Except for all our commotion, the street—which seems to be the only real street in the village—is empty. We pass a large stone fountain in the middle of the tiny square, pouring out fresh acqua from its spout. We keep walking, suitcase wheels taking a beating, past a vending machine that sells contact lenses, past the parish church, past white plastic tables and chairs in a shaded courtyard, and finally arrive at the pensione where we would spend the next few days of summer.

Just down the hill, a half mile away, the Mediterranean glistened, a brilliant blue. We drove along it on our way here from the Palermo airport, and we would step into its waters several times over the next two weeks to let ourselves be cooled by the sea. We would wade in it and plunge into it here in the north, and a week later, far on the other side, the southern coast of Sicily. In between, we would see ruins and castles, we’d get lost, eat gelato, light candles in dark churches, and pray under stars. And every moment of it, I would look for him.

It was like that every day at home, anyway, so why not? Why not take that daily routine of remembering and searching, of excavation of life and death, those memories of my husband laughing, of his body cooling under a blue sheet, that constant deep, frantic prayer for his little boys, why not take the cross and the empty tomb, weeping mothers and wounds probed by a doubter—why not take it all out of a beige- colored third-floor apartment in an Alabama summer, heavy with humidity, memories, and landmarks, why not wrest the top off the bottle of the past and spill it out here?

In the pictures in the guidebooks to Sicily, all I saw was the past, remnants of what was dead and gone. It seemed right. Maybe here in Sicily, picking my way on worn- down paths around tumbling ancient walls and broken columns, I will catch a clue as to how to live with it all. And because here the veil between past and present seems as thin as the cooling breeze from the sea, maybe, just once in a while, it will whip aside, it will lift, and I’ll see.

***

This book is about how we got from here to there, from February to June, from Alabama to Sicily, and why. It’s not my autobiography or his biography or a portrait of our marriage. It’s not a theological treatise on the Last Things—far from it—or a guide on how to live with grief. It’s a memoir of what we—mostly I—went through, thought, prayed, and did during a trip to Sicily, a place I had never once before thought about going in forty-nine years of life, a trip I impulsively planned about a month after my husband died of a heart attack.

I wrote it because, as a longtime book, column, and blog writer about matters of faith and life, I could not avoid writing about grief and loss and faith in the months after Mike’s death. I did wait, though. I hesitated every time before tapping the “publish” button on my blog because I didn’t want to be seen as seeking sympathy or exploiting it. Exploiting him.

But then every time I would go ahead and post a blog entry related to grief, readers’ reactions—as they thanked me and, most helpfully, shared their own experiences—convinced me it might be all right.

There was something else, too.

People kept dying. They just wouldn’t stop.

The mother of one of my daughter’s classmates, a woman younger than I am, dropped dead of an aneurysm. Two weeks later, another classmate of Katie’s died in a car accident.

An online friend of mine, a fellow writer nicknamed the “Internet Monk,” Michael Spencer, was diagnosed with cancer in the late fall and died the day after Easter, aged fi fty-two.

The fall after Mike died, in fact, eight months to the day, on October 3, my good friend Molly, who lived in Florida, died. She had taught my children, I hers, and she had been battling various forms of cancer for years. That evening, one of her daughters wrote, she “went peacefully home.”

If we are Christians, we have two kinds of hope constantly held out to us: the hope that the cross gives, that our sins have no more power over us, that in our suffering we are not alone, that God knows, that God suffers, mysteriously with us; and the hope of the empty tomb, that death has no more power over us either, that Jesus Christ lives.

But still, in the midst of the hope, the pietà remains. There is Our Lady of Sorrows, there is the mother standing at the cross, weeping, there are the friends, uncomprehending and regretful, there is a suddenly empty space and strange silence, there are the doubters scoffing from afar, challenging, Where is your hope now?

So we went to Sicily, to see.

Recenzii

"Amy Welborn's latest book is a must-read spiritual treasure. It reveals not only the heart-wrenching dynamics of grief but also the odd and wonderful way grace illuminates even the thickest darkness. Funny, engagingly written, spiritually profound, Wish You Were Here is a gem." —Robert Baron, author of Catholicism: A Journey to the Heart of the Faith

“Amy Welborn says it best: ‘Everything but love has been burned away and a feast awaits.’ A brave and true memoir of grief, resurrected.”

—Heather King, author of Shirt of Flame: A Year with Saint Thérèse of Lisieux

“Amy Welborn says it best: ‘Everything but love has been burned away and a feast awaits.’ A brave and true memoir of grief, resurrected.”

—Heather King, author of Shirt of Flame: A Year with Saint Thérèse of Lisieux