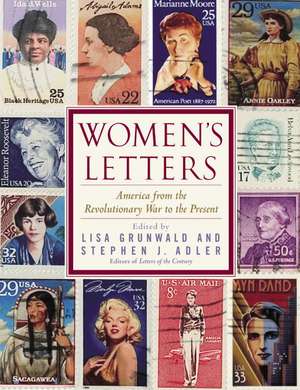

Women's Letters: America from the Revolutionary War to the Present

Autor Stephen J. Adler, Lisa Grunwalden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2008

New York City firefighter, asking him, “Were you afraid?”

The letters gathered here also offer fresh insight into the personal milestones in women’s lives. Here is a mid-nineteenth-century missionary describing a mastectomy performed without anesthesia; Marilyn Monroe asking her doctor to spare her ovaries in a handwritten note she taped to her stomach before appendix surgery; an eighteen-year-old telling her mother about her decision to have an abortion the year after Roe v. Wade; and a woman writing to her parents and in-laws about adopting a Chinese baby.

With more than 400 letters and over 100 stunning photographs, Women’s Letters is a work of astonishing breadth and scope, and a remarkable testament to the women who lived–and made–history.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 149.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 225

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.65€ • 29.60$ • 23.84£

28.65€ • 29.60$ • 23.84£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385335560

ISBN-10: 0385335563

Pagini: 824

Dimensiuni: 181 x 232 x 43 mm

Greutate: 1.42 kg

Editura: Dial Press

ISBN-10: 0385335563

Pagini: 824

Dimensiuni: 181 x 232 x 43 mm

Greutate: 1.42 kg

Editura: Dial Press

Notă biografică

Lisa Grunwald is the author of the novels Whatever Makes You Happy, New Year’s Eve, The Theory of Everything, and Summer. She is a former magazine editor.

Stephen J. Adler is editor in chief of Business Week magazine and author of The Jury: Trial and Error in the American Courtroom. Grunwald and Adler live with their two children in New York City.

From the Hardcover edition.

Stephen J. Adler is editor in chief of Business Week magazine and author of The Jury: Trial and Error in the American Courtroom. Grunwald and Adler live with their two children in New York City.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Revolution

1775-1799

I hear by Captn Wm Riley news that makes me very Sorry for he Says you proved a Grand Coward when the fight was at Bunkers hill. . . . If you are afraid pray own the truth & come home & take care of our Children & I will be Glad to Come & take your place, & never will be Called a Coward, neither will I throw away one Cartridge but exert myself bravely in so good a Cause.

—Abigail Grant to her husband

August 19, 1776

BETWEEN 1775 AND 1799 . . . 1775: Patrick Henry attempts to persuade Virginia to arm its militia against the British, declaring: “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death.” The first shots of the Revolutionary War are fired at Lexington and Concord. In Salem, following the first news of the war, 13-year-old Susan Mason Smith chooses not to remove her shoes for several days, wanting to be prepared in case her family decides to flee. Only about half the white women in the colonies are literate enough to sign their names. 1776: With her husband, John, away at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Abigail Adams writes to him frequently and urges him to make sure that he and his colleagues “Remember the Ladies” while they are shaping the new nation; if they don’t, she warns him, “we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.” Thomas Paine publishes Common Sense, a 50-page pamphlet that urges Americans to fight not only against taxation but also for independence; it sells more than half a million copies within its first few months. Betsy Ross (according to the legend that’s been neither proven nor refuted by evidence) is visited by George Washington and asked to make a national flag; the stars on her design will have five points, rather than the six Washington suggests. In his first draft of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson writes: “We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness.” For 67 days, the new country is called “The United Colonies of America”; in September, Congress gives the USA its official name. 1777: Sybil Ludington, the 16-year-old daughter of a New York militia officer, rides almost 40 miles to muster troops against the British. More than 100 women gather at the Boston store of Thomas Boylston to protest the merchant’s high wartime prices. General George Washington leads 11,000 militiamen to Valley Forge near British-occupied Philadelphia, where they are forced to spend a bitterly cold winter, plagued by widespread dysentery and typhus and a severe lack of food, clothes, and basic supplies. Washington writes in a letter that the soldiers’ “marches might be tracked by the blood from their feet.” 1778: During the Battle of Monmouth Court House in New Jersey, Mary McCauly earns the name “Molly Pitcher” after making frequent trips with water to cool down both the men and the cannon in her husband’s regiment. 1781: Los Angeles is founded by Spanish settlers; its full name is El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles de Porciuncula. 1783: The British evacuate New York. The Paris Peace Treaty ends the Revolutionary War. New Jersey, alone among the 13 states, enacts a statute giving women the vote; it will be put into sporadic use starting in 1787—and overturned in 1807. 1784: Abel Buell engraves and publishes the first map of the United States, “layd down from the latest observations and best authority agreeable to the peace of 1783.” Judith Sergeant Murray publishes her essay “Desultory Thoughts upon the Utility of Encouraging a Degree of Self-Complacency, Especially in Female Bosoms,” arguing that in the absence of sufficient confidence, women all too often marry precipitously to avoid the epithet spinster. 1786: In his sermon “On Dress,” John Wesley declares: “slovenliness is no part of religion. . . . ‘Cleanliness is, indeed, next to godliness,’ ” but warns: “The wearing [of] gay or costly apparel naturally tends to breed and to increase vanity. . . . You know in your hearts, it is with a view to be admired that you thus adorn yourselves, and that you would not be at the pains were none to see you but God and his holy angels.” 1787: Despite Congress’s plan merely to revise the 1777 Articles of Confederation, delegates draft a new constitution that gives increased power to a central government. 1788: Nine states ratify the Constitution, and it goes into effect. 1789: Though rich in land, George Washington must borrow £600 in cash to travel from Mount Vernon to New York City for his inauguration. 1790: The total population of the United States is 3,893,874, of whom 694,207 are slaves. Among white males, 791,901 are under the age of 16; 807,312 are 16 and over. 1791: Vermont becomes the fourteenth state. The national debt is $75,463,000, or roughly $18 a person. The Bill of Rights is ratified. 1792: George Washington signs an act providing for the creation of copper pennies and stipulating that “no copper coins or pieces whatsoever except the said cents and half-cents, shall pass current as money.” The Old Farmer’s Almanac debuts, offering weather predictions, tide tables, and occasional advice; it costs sixpence and has a first-year circulation of 3,000 that will triple in a year and after two centuries pass four million. 1794: Eli Whitney is granted a patent for the cotton gin, which combs and deseeds cotton 10 times faster than the nonmechanical process. 1796: Amelia Simmons publishes the first American cookbook under the title American Cookery, or the Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables, and the Best Modes of Making Puff-Pastries, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, from the Imperial Plum to Plain Cake—Adapted to This Country and All Grades of Life. 1798: More than 2,000 people die in a yellow fever epidemic in New York City. 1799: A Philadelphia Quaker named Elizabeth Drinker writes in her journal about the nearly novel experience of taking a bath: “I bore it better than I expected, not having been wett all over att once, for 28 years past.”

1775: Circa April 18

Rachel Revere to Paul Revere

On April 18, 1775, Paul Revere (1735–1818) made his famous midnight ride to Lexington, Massachusetts, warning his countrymen of the British troops’ planned attack. Revere was captured later that night, but his actions marshaled colonial troops to the famous first battle on Lexington Green, where the American Revolution began the next day. Once released, Revere started back toward Boston, despite having neither money nor horse. With this note, his worried wife, Rachel Walker Revere (1745–1813), tried to send him help. Dr. Benjamin Church was trusted by Rachel as a fellow rebel but was in fact a British spy. Rachel’s letter was promptly turned over to the British.

My dear by Doctr Church I send a hundred & twenty five pounds and beg you will take the best care of your self and not attempt coming in to this town again and if I have an opportunity of coming or sending out any thing or any of the Children I shall do it pray keep up your spirits and trust your self and us in the hands of a good God who will take care of us tis all my dependance for vain is the help of man aduie my

Love from your

affectionate R Revere

1775: April 22

Anne Hulton to Elizabeth Lightbody

Anne Hulton (?–1779) was a sister of Boston’s commissioner of customs and, like some 15 to 35 percent of the white colonial population, a British Loyalist. In this letter to her friend Elizabeth Lightbody, in Liverpool, she described the beginning of the war as it would come to be seen on the other side of the Atlantic, right down to the outrage of having His Majesty’s troops attacked from behind trees and fences. By the end of the year, having endured months in a besieged city, Hulton would sail for England.

Inst was a common abbreviation for instant, meaning “the month this was written.” The Grenadiers were elite British troops who wore long red coats and tall bearskin hats. A magazine, in this context, was a warehouse. Hugh Percy was a British brigadier general. The Otter was a British sloop that would engage in battle in the first week of May.

I acknowledged the receipt of My Dear Friends kind favor of the 20th Septr the begin’ing of last Month, tho’ did not fully Answer it, purposing as I intimated to write again soon, be assured as your favors are always very acceptable, so nothing you say, passes unnoticed, or appears unimportant to me. but at present my mind is too much agitated to attend to any subject but one, and it is that which you will be most desirous to hear particulars of, I doubt not in regard to your friends here, as to our Situation, as well as the Publick events. I will give you the best account I can, which you may rely on for truth.

On the 18th instt at 11 at Night, about 800 Grenadiers & light Infantry were ferry’d across the Bay to Cambridge, from whence they marchd to Concord, about 20 Miles. The Congress had been lately assembled at that place, & it was imagined that the General had intelligence of a Magazine being formed there & that they were going to destroy it.

The People in the Country (who are all furnished with Arms & have what they call Minute Companys in every Town ready to march on any alarm), had a signal it’s supposed by a light from one of the Steeples in Town, Upon the Troops embarkg. The alarm spread thro’ the Country, so that before daybreak the people in general were in Arms & on their March to Concord. About Daybreak a number of the People appeard before the Troops near Lexington. They were called to, to disperse. when they fired on the Troops & ran off, Upon which the Light Infantry pursued them & brought down about fifteen of them. The Troops went on to Concord & executed the business they were sent on, & on their return found two or three of their people Lying in the Agonies of Death, scalp’d & their Noses & ears cut off & Eyes bored out—Which exasperated the Soldiers exceedingly—a prodigious number of the People now occupying the Hills, woods, & Stone Walls along the road. The Light Troops drove some parties from the hills, but all the road being inclosed with Stone Walls Served as a cover to the Rebels, from whence they fired on the Troops still running off whenever they had fired, but still supplied by fresh Numbers who came from many parts of the Country. In this manner were the Troops harrased in thier return for Seven on eight Miles, they were almost exhausted & had expended near the whole of their Ammunition when to their great joy they were releived by a Brigade of Troops under the command of Lord Percy with two pieces of Artillery. The Troops now combated with fresh Ardour, & marched in their return with undaunted countenances, recieving Sheets of fire all the way for many Miles, yet having no visible Enemy to combat with, for they never woud face ’em in an open field, but always skulked & fired from behind Walls, & trees, & out of Windows of Houses, but this cost them dear for the Soldiers enterd those dwellings, & put all the Men to death. Lord Percy has gained great honor by his conduct thro’ this day of severe Servise, he was exposed to the hottest of the fire & animated the Troops with great coolness & spirit. Several officers are wounded & about 100 Soldiers. The killed amount to near 50, as to the Enemy we can have no exact acct but it is said there was about ten times the Number of them engaged, & that near 1000 of ’em have fallen

The Troops returned to Charlestown about Sunset after having some of ’em marched near fifty miles, & being engaged from Daybreak in Action, without respite, or refreshment, & about ten in the Evening they were brought back to Boston. The next day the Country pourd down its Thousands, and at this time from the entrance of Boston Neck at Roxbury round by Cambridge to Charlestown is surrounded by at least 20,000 Men, who are raising batteries on three or four different Hills. We are now cut off from all communication with the Country & many people must soon perish with famine in this place. Some families have laid in store of Provissions against a Siege. We are threatned that whilst the Out Lines are attacked wth a rising of the Inhabitants within, & fire & sword, a dreadful prospect before us, and you know how many & how dear are the objects of our care. The Lord preserve us all & grant us an happy Issue out of these troubles.

For several nights past, I have expected to be roused by the firing of Cannon. Tomorrow is Sunday, & we may hope for one day of rest, at present a Solemn dead silence reigns in the Streets, numbers have packed up their effects, & quited the Town, but the General has put a Stop to any more removing, & here remains in Town about 9000 Souls (besides the Servants of the Crown) These are the greatest Security, the General declared that if a Gun is fired within the Town the inhabitants shall fall a Sacrifice. Amidst our distress & apprehension, I am rejoyced our British Hero was preserved, My Lord Percy had a great many & miraculous escapes in the late Action. This amiable Young Nobleman with the Graces which attracts Admiration, possesses the virtues of the heart, & all those qualities that form the great Soldier—Vigilent Active, temperate, humane, great Command of temper, fortitude in enduring hardships & fatigue, & Intrepidity in dangers. His Lordships behavior in the day of trial has done honor to the Percys. indeed all the Officers & Soldiers behaved with the greatest bravery it is said

I hope you and yours are all well & shall be happy to hear so. I woud beg of you whenever you write to mention the dates of my Letters which you have rec’d since you wrote specialy my last of March 2d

I am not able at present to write to our Dear friends at Chester woud desire the favor of you to write as soon as you receive this, & present my respects to your & my friends there, and likewise the same to those who are near to you.

I wrote not long ago both to Miss Tylston & to my Aunt H:—have not heard yet from the Bahamas

Have never heard from Mr Gildart or Mr Earl yet

The Otter Man of War is just arrived Sunday Morng

What is marked with these Lines, you are at Liberty to make as publick as you please Let the merits of Lord Percy be known as far as you can.

1775: April 29

Christian Barnes to Elizabeth Inman

A known Loyalist, merchant Henry “Tory” Barnes was forced to leave his home in Marlborough, Massachusetts, to avoid capture. Terrified by the visit of a rebel soldier, Barnes’s wife, Christian, described the incident to Elizabeth Inman (1726–1786), a Cambridge friend who shared her sympathies, if not her immediate peril. Along with hundreds of others who sympathized with the British, Henry Barnes would be officially banished from Boston in the fall.

It is now a week since I had a line from my dear Mrs. Inman, in which time I have had some severe trials, but the greatest terror I was ever thrown into was on Sunday last. A man came up to the gate and loaded his musket, and before I could determine which way to run he entered the house and demanded a dinner. I sent him the best I had upon the table. He was not contented, but insisted upon bringing in his gun and dining with me; this terrified the young folks, and they ran out of the house. I went in and endeavored to pacify him by every method in my power, but I found it was to no purpose. He still continued to abuse me, and said when he had eat his dinner he should want a horse and if I did not let him have one he would blow my brains out. He pretended to have an order from the General for one of my horses, but did not produce it. His language was so dreadful and his looks so frightful that I could not remain in the house, but fled to the store and locked myself in. He followed me and declared he would break the door open. Some people very luckily passing to meeting prevented his doing any mischief and staid by me until he was out of sight, but I did not recover from my fright for several days. The sound of drum or the sight of a gun put me into such a tremor that I could not command myself. I have met with but little molestation since this affair, which I attribute to the protection sent me by Col. Putnam and Col. Whitcomb. I returned them a card of thanks for their goodness tho’ I knew it was thro’ your interest I obtained this favor. . . . The people here are weary at [Mr. Barnes’s] absence, but at the same time give it as their opinion that he could not pass the guards. . . . I do not doubt but upon a proper remonstrance I might procure a pass for him through the Camp from our two good Colonels. . . . I know he must be very unhappy in Boston. It was never his intention to quit his family. . . .

1775: Circa June 15

Sarah Deming to Sally Coverley

All we know about Sarah Winslow Deming (1722–1788) is that she was born in Massachusetts, the daughter of John and Sarah Winslow, and that, as this letter attests, she was a terrified witness to the very beginnings of the American Revolution. The troops she referred to were British, and this letter to her niece was a vivid reminder that the war would be fought not in far-off battlefields, but on the colonists’ doorsteps.

General Thomas Gage was Britain’s military governor of Massachusetts. Aceldama refers to the land Judas purchased with the money he received for betraying Christ; the word means “field of blood.” The Sally Sarah referred to in the letter was a different niece; Lucinda was a servant.

My Dear Niece

I engaged to give you & by you your papa and mamma some account of my peregrinations with the reasons thereof. The cause is too well known to need a word upon it.

I was very unquiet from the moment I was informed that more troops were coming to Boston. ’Tis true that those who had wintered there, had not given us much molestation, but an additional strength I dreaded and determined if possible to get out of their reach, and to take with me as much of my little interest as I could. Your uncle Deming was very far from being of my mind from which has proceeded those diflcutics which peculiarly related to myself—but I now say not a word of this to him; we are joint sufferers and no doubt it is God’s will that it should be so.

Many a time have I thought that could I be out of Boston together with my family and my friends, I could be content with the meanest fare and slenderest accommodation. Out of Boston, out of Boston at almost any rate—away as far as possible from the infection of smallpox & the din of drums & martial musick as it is called and horrors of war—but my distress is not to be described—I attempt not to describe it.

On Saterday the 15th April p.m. I had a visit from Mr. Barrow. I never saw him with such a countenance.

The Monday following, April 17, I was told that all the boats belonging to the men of war were launched on Saterday night while the town inhabitants were sleeping except some faithful watchmen who gave the intelligence. In the evening Mr. Deming wrote to Mr Withington of Dorchester to come over with his carts the very first fair day (the evening of this day promising rain on the next, which accordingly fell in plenty) to carry off our best goods.

On Tuesday evening 18 April we were informed that the companies above mentioned were in motion, that the men of war boats were rowed round to Charlestown ferry, Barton’s point and bottom of ye common, that the soldiers were run thro the streets on tip toe (the moon not having risen) in the dark of ye evening, that there were a number of handcuffs in one of the boats, which were taken at the long wharf, & that two days provision had been cooked for ’em on board one of the transport ships lying in ye harbor. That whatever other business they might have, the main was to take possession of the bodies of Mess. Adams & Hancock whom they & we knew where they were lodged. We had no doubt of the truth of all this, and that expresses were sent forth both over the neck & Charlestown ferry to give our friends timely notice that they might escape. N.B. I did not git to bed this night till after 12 oclock, nor to sleep till long after that, and then my sleep was much broken as it had been for many nights before.

Early on Wednesday the fatal 19th April before I had quited my chamber one after another came running to tell me that the kings troops had fired upon and killed 8 of our neighbors at Lexington in their way to Concord.

All the intelligence of this day was dreadful. Almost every countenance expressing anxiety and distress: but description fails here. I went to bed about 12 o. c. this night, having taken but little food thro the day, having resolved to quit the town before the next setting sun, should life and limbs be spared me. Towards morning I fell into a profound sleep, from which I was waked by Mr. Deming between 6 and 7 o. c. informing me that I was Gen. Gage’s prisoner all egress & regress being cut off between the town and the country. Here again description fails. No words can paint my distress—I feel it at this instant (just eight weeks after) so sensibly that I must pause before I proceed.

From the Hardcover edition.

1775-1799

I hear by Captn Wm Riley news that makes me very Sorry for he Says you proved a Grand Coward when the fight was at Bunkers hill. . . . If you are afraid pray own the truth & come home & take care of our Children & I will be Glad to Come & take your place, & never will be Called a Coward, neither will I throw away one Cartridge but exert myself bravely in so good a Cause.

—Abigail Grant to her husband

August 19, 1776

BETWEEN 1775 AND 1799 . . . 1775: Patrick Henry attempts to persuade Virginia to arm its militia against the British, declaring: “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death.” The first shots of the Revolutionary War are fired at Lexington and Concord. In Salem, following the first news of the war, 13-year-old Susan Mason Smith chooses not to remove her shoes for several days, wanting to be prepared in case her family decides to flee. Only about half the white women in the colonies are literate enough to sign their names. 1776: With her husband, John, away at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Abigail Adams writes to him frequently and urges him to make sure that he and his colleagues “Remember the Ladies” while they are shaping the new nation; if they don’t, she warns him, “we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.” Thomas Paine publishes Common Sense, a 50-page pamphlet that urges Americans to fight not only against taxation but also for independence; it sells more than half a million copies within its first few months. Betsy Ross (according to the legend that’s been neither proven nor refuted by evidence) is visited by George Washington and asked to make a national flag; the stars on her design will have five points, rather than the six Washington suggests. In his first draft of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson writes: “We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness.” For 67 days, the new country is called “The United Colonies of America”; in September, Congress gives the USA its official name. 1777: Sybil Ludington, the 16-year-old daughter of a New York militia officer, rides almost 40 miles to muster troops against the British. More than 100 women gather at the Boston store of Thomas Boylston to protest the merchant’s high wartime prices. General George Washington leads 11,000 militiamen to Valley Forge near British-occupied Philadelphia, where they are forced to spend a bitterly cold winter, plagued by widespread dysentery and typhus and a severe lack of food, clothes, and basic supplies. Washington writes in a letter that the soldiers’ “marches might be tracked by the blood from their feet.” 1778: During the Battle of Monmouth Court House in New Jersey, Mary McCauly earns the name “Molly Pitcher” after making frequent trips with water to cool down both the men and the cannon in her husband’s regiment. 1781: Los Angeles is founded by Spanish settlers; its full name is El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles de Porciuncula. 1783: The British evacuate New York. The Paris Peace Treaty ends the Revolutionary War. New Jersey, alone among the 13 states, enacts a statute giving women the vote; it will be put into sporadic use starting in 1787—and overturned in 1807. 1784: Abel Buell engraves and publishes the first map of the United States, “layd down from the latest observations and best authority agreeable to the peace of 1783.” Judith Sergeant Murray publishes her essay “Desultory Thoughts upon the Utility of Encouraging a Degree of Self-Complacency, Especially in Female Bosoms,” arguing that in the absence of sufficient confidence, women all too often marry precipitously to avoid the epithet spinster. 1786: In his sermon “On Dress,” John Wesley declares: “slovenliness is no part of religion. . . . ‘Cleanliness is, indeed, next to godliness,’ ” but warns: “The wearing [of] gay or costly apparel naturally tends to breed and to increase vanity. . . . You know in your hearts, it is with a view to be admired that you thus adorn yourselves, and that you would not be at the pains were none to see you but God and his holy angels.” 1787: Despite Congress’s plan merely to revise the 1777 Articles of Confederation, delegates draft a new constitution that gives increased power to a central government. 1788: Nine states ratify the Constitution, and it goes into effect. 1789: Though rich in land, George Washington must borrow £600 in cash to travel from Mount Vernon to New York City for his inauguration. 1790: The total population of the United States is 3,893,874, of whom 694,207 are slaves. Among white males, 791,901 are under the age of 16; 807,312 are 16 and over. 1791: Vermont becomes the fourteenth state. The national debt is $75,463,000, or roughly $18 a person. The Bill of Rights is ratified. 1792: George Washington signs an act providing for the creation of copper pennies and stipulating that “no copper coins or pieces whatsoever except the said cents and half-cents, shall pass current as money.” The Old Farmer’s Almanac debuts, offering weather predictions, tide tables, and occasional advice; it costs sixpence and has a first-year circulation of 3,000 that will triple in a year and after two centuries pass four million. 1794: Eli Whitney is granted a patent for the cotton gin, which combs and deseeds cotton 10 times faster than the nonmechanical process. 1796: Amelia Simmons publishes the first American cookbook under the title American Cookery, or the Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables, and the Best Modes of Making Puff-Pastries, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, from the Imperial Plum to Plain Cake—Adapted to This Country and All Grades of Life. 1798: More than 2,000 people die in a yellow fever epidemic in New York City. 1799: A Philadelphia Quaker named Elizabeth Drinker writes in her journal about the nearly novel experience of taking a bath: “I bore it better than I expected, not having been wett all over att once, for 28 years past.”

1775: Circa April 18

Rachel Revere to Paul Revere

On April 18, 1775, Paul Revere (1735–1818) made his famous midnight ride to Lexington, Massachusetts, warning his countrymen of the British troops’ planned attack. Revere was captured later that night, but his actions marshaled colonial troops to the famous first battle on Lexington Green, where the American Revolution began the next day. Once released, Revere started back toward Boston, despite having neither money nor horse. With this note, his worried wife, Rachel Walker Revere (1745–1813), tried to send him help. Dr. Benjamin Church was trusted by Rachel as a fellow rebel but was in fact a British spy. Rachel’s letter was promptly turned over to the British.

My dear by Doctr Church I send a hundred & twenty five pounds and beg you will take the best care of your self and not attempt coming in to this town again and if I have an opportunity of coming or sending out any thing or any of the Children I shall do it pray keep up your spirits and trust your self and us in the hands of a good God who will take care of us tis all my dependance for vain is the help of man aduie my

Love from your

affectionate R Revere

1775: April 22

Anne Hulton to Elizabeth Lightbody

Anne Hulton (?–1779) was a sister of Boston’s commissioner of customs and, like some 15 to 35 percent of the white colonial population, a British Loyalist. In this letter to her friend Elizabeth Lightbody, in Liverpool, she described the beginning of the war as it would come to be seen on the other side of the Atlantic, right down to the outrage of having His Majesty’s troops attacked from behind trees and fences. By the end of the year, having endured months in a besieged city, Hulton would sail for England.

Inst was a common abbreviation for instant, meaning “the month this was written.” The Grenadiers were elite British troops who wore long red coats and tall bearskin hats. A magazine, in this context, was a warehouse. Hugh Percy was a British brigadier general. The Otter was a British sloop that would engage in battle in the first week of May.

I acknowledged the receipt of My Dear Friends kind favor of the 20th Septr the begin’ing of last Month, tho’ did not fully Answer it, purposing as I intimated to write again soon, be assured as your favors are always very acceptable, so nothing you say, passes unnoticed, or appears unimportant to me. but at present my mind is too much agitated to attend to any subject but one, and it is that which you will be most desirous to hear particulars of, I doubt not in regard to your friends here, as to our Situation, as well as the Publick events. I will give you the best account I can, which you may rely on for truth.

On the 18th instt at 11 at Night, about 800 Grenadiers & light Infantry were ferry’d across the Bay to Cambridge, from whence they marchd to Concord, about 20 Miles. The Congress had been lately assembled at that place, & it was imagined that the General had intelligence of a Magazine being formed there & that they were going to destroy it.

The People in the Country (who are all furnished with Arms & have what they call Minute Companys in every Town ready to march on any alarm), had a signal it’s supposed by a light from one of the Steeples in Town, Upon the Troops embarkg. The alarm spread thro’ the Country, so that before daybreak the people in general were in Arms & on their March to Concord. About Daybreak a number of the People appeard before the Troops near Lexington. They were called to, to disperse. when they fired on the Troops & ran off, Upon which the Light Infantry pursued them & brought down about fifteen of them. The Troops went on to Concord & executed the business they were sent on, & on their return found two or three of their people Lying in the Agonies of Death, scalp’d & their Noses & ears cut off & Eyes bored out—Which exasperated the Soldiers exceedingly—a prodigious number of the People now occupying the Hills, woods, & Stone Walls along the road. The Light Troops drove some parties from the hills, but all the road being inclosed with Stone Walls Served as a cover to the Rebels, from whence they fired on the Troops still running off whenever they had fired, but still supplied by fresh Numbers who came from many parts of the Country. In this manner were the Troops harrased in thier return for Seven on eight Miles, they were almost exhausted & had expended near the whole of their Ammunition when to their great joy they were releived by a Brigade of Troops under the command of Lord Percy with two pieces of Artillery. The Troops now combated with fresh Ardour, & marched in their return with undaunted countenances, recieving Sheets of fire all the way for many Miles, yet having no visible Enemy to combat with, for they never woud face ’em in an open field, but always skulked & fired from behind Walls, & trees, & out of Windows of Houses, but this cost them dear for the Soldiers enterd those dwellings, & put all the Men to death. Lord Percy has gained great honor by his conduct thro’ this day of severe Servise, he was exposed to the hottest of the fire & animated the Troops with great coolness & spirit. Several officers are wounded & about 100 Soldiers. The killed amount to near 50, as to the Enemy we can have no exact acct but it is said there was about ten times the Number of them engaged, & that near 1000 of ’em have fallen

The Troops returned to Charlestown about Sunset after having some of ’em marched near fifty miles, & being engaged from Daybreak in Action, without respite, or refreshment, & about ten in the Evening they were brought back to Boston. The next day the Country pourd down its Thousands, and at this time from the entrance of Boston Neck at Roxbury round by Cambridge to Charlestown is surrounded by at least 20,000 Men, who are raising batteries on three or four different Hills. We are now cut off from all communication with the Country & many people must soon perish with famine in this place. Some families have laid in store of Provissions against a Siege. We are threatned that whilst the Out Lines are attacked wth a rising of the Inhabitants within, & fire & sword, a dreadful prospect before us, and you know how many & how dear are the objects of our care. The Lord preserve us all & grant us an happy Issue out of these troubles.

For several nights past, I have expected to be roused by the firing of Cannon. Tomorrow is Sunday, & we may hope for one day of rest, at present a Solemn dead silence reigns in the Streets, numbers have packed up their effects, & quited the Town, but the General has put a Stop to any more removing, & here remains in Town about 9000 Souls (besides the Servants of the Crown) These are the greatest Security, the General declared that if a Gun is fired within the Town the inhabitants shall fall a Sacrifice. Amidst our distress & apprehension, I am rejoyced our British Hero was preserved, My Lord Percy had a great many & miraculous escapes in the late Action. This amiable Young Nobleman with the Graces which attracts Admiration, possesses the virtues of the heart, & all those qualities that form the great Soldier—Vigilent Active, temperate, humane, great Command of temper, fortitude in enduring hardships & fatigue, & Intrepidity in dangers. His Lordships behavior in the day of trial has done honor to the Percys. indeed all the Officers & Soldiers behaved with the greatest bravery it is said

I hope you and yours are all well & shall be happy to hear so. I woud beg of you whenever you write to mention the dates of my Letters which you have rec’d since you wrote specialy my last of March 2d

I am not able at present to write to our Dear friends at Chester woud desire the favor of you to write as soon as you receive this, & present my respects to your & my friends there, and likewise the same to those who are near to you.

I wrote not long ago both to Miss Tylston & to my Aunt H:—have not heard yet from the Bahamas

Have never heard from Mr Gildart or Mr Earl yet

The Otter Man of War is just arrived Sunday Morng

What is marked with these Lines, you are at Liberty to make as publick as you please Let the merits of Lord Percy be known as far as you can.

1775: April 29

Christian Barnes to Elizabeth Inman

A known Loyalist, merchant Henry “Tory” Barnes was forced to leave his home in Marlborough, Massachusetts, to avoid capture. Terrified by the visit of a rebel soldier, Barnes’s wife, Christian, described the incident to Elizabeth Inman (1726–1786), a Cambridge friend who shared her sympathies, if not her immediate peril. Along with hundreds of others who sympathized with the British, Henry Barnes would be officially banished from Boston in the fall.

It is now a week since I had a line from my dear Mrs. Inman, in which time I have had some severe trials, but the greatest terror I was ever thrown into was on Sunday last. A man came up to the gate and loaded his musket, and before I could determine which way to run he entered the house and demanded a dinner. I sent him the best I had upon the table. He was not contented, but insisted upon bringing in his gun and dining with me; this terrified the young folks, and they ran out of the house. I went in and endeavored to pacify him by every method in my power, but I found it was to no purpose. He still continued to abuse me, and said when he had eat his dinner he should want a horse and if I did not let him have one he would blow my brains out. He pretended to have an order from the General for one of my horses, but did not produce it. His language was so dreadful and his looks so frightful that I could not remain in the house, but fled to the store and locked myself in. He followed me and declared he would break the door open. Some people very luckily passing to meeting prevented his doing any mischief and staid by me until he was out of sight, but I did not recover from my fright for several days. The sound of drum or the sight of a gun put me into such a tremor that I could not command myself. I have met with but little molestation since this affair, which I attribute to the protection sent me by Col. Putnam and Col. Whitcomb. I returned them a card of thanks for their goodness tho’ I knew it was thro’ your interest I obtained this favor. . . . The people here are weary at [Mr. Barnes’s] absence, but at the same time give it as their opinion that he could not pass the guards. . . . I do not doubt but upon a proper remonstrance I might procure a pass for him through the Camp from our two good Colonels. . . . I know he must be very unhappy in Boston. It was never his intention to quit his family. . . .

1775: Circa June 15

Sarah Deming to Sally Coverley

All we know about Sarah Winslow Deming (1722–1788) is that she was born in Massachusetts, the daughter of John and Sarah Winslow, and that, as this letter attests, she was a terrified witness to the very beginnings of the American Revolution. The troops she referred to were British, and this letter to her niece was a vivid reminder that the war would be fought not in far-off battlefields, but on the colonists’ doorsteps.

General Thomas Gage was Britain’s military governor of Massachusetts. Aceldama refers to the land Judas purchased with the money he received for betraying Christ; the word means “field of blood.” The Sally Sarah referred to in the letter was a different niece; Lucinda was a servant.

My Dear Niece

I engaged to give you & by you your papa and mamma some account of my peregrinations with the reasons thereof. The cause is too well known to need a word upon it.

I was very unquiet from the moment I was informed that more troops were coming to Boston. ’Tis true that those who had wintered there, had not given us much molestation, but an additional strength I dreaded and determined if possible to get out of their reach, and to take with me as much of my little interest as I could. Your uncle Deming was very far from being of my mind from which has proceeded those diflcutics which peculiarly related to myself—but I now say not a word of this to him; we are joint sufferers and no doubt it is God’s will that it should be so.

Many a time have I thought that could I be out of Boston together with my family and my friends, I could be content with the meanest fare and slenderest accommodation. Out of Boston, out of Boston at almost any rate—away as far as possible from the infection of smallpox & the din of drums & martial musick as it is called and horrors of war—but my distress is not to be described—I attempt not to describe it.

On Saterday the 15th April p.m. I had a visit from Mr. Barrow. I never saw him with such a countenance.

The Monday following, April 17, I was told that all the boats belonging to the men of war were launched on Saterday night while the town inhabitants were sleeping except some faithful watchmen who gave the intelligence. In the evening Mr. Deming wrote to Mr Withington of Dorchester to come over with his carts the very first fair day (the evening of this day promising rain on the next, which accordingly fell in plenty) to carry off our best goods.

On Tuesday evening 18 April we were informed that the companies above mentioned were in motion, that the men of war boats were rowed round to Charlestown ferry, Barton’s point and bottom of ye common, that the soldiers were run thro the streets on tip toe (the moon not having risen) in the dark of ye evening, that there were a number of handcuffs in one of the boats, which were taken at the long wharf, & that two days provision had been cooked for ’em on board one of the transport ships lying in ye harbor. That whatever other business they might have, the main was to take possession of the bodies of Mess. Adams & Hancock whom they & we knew where they were lodged. We had no doubt of the truth of all this, and that expresses were sent forth both over the neck & Charlestown ferry to give our friends timely notice that they might escape. N.B. I did not git to bed this night till after 12 oclock, nor to sleep till long after that, and then my sleep was much broken as it had been for many nights before.

Early on Wednesday the fatal 19th April before I had quited my chamber one after another came running to tell me that the kings troops had fired upon and killed 8 of our neighbors at Lexington in their way to Concord.

All the intelligence of this day was dreadful. Almost every countenance expressing anxiety and distress: but description fails here. I went to bed about 12 o. c. this night, having taken but little food thro the day, having resolved to quit the town before the next setting sun, should life and limbs be spared me. Towards morning I fell into a profound sleep, from which I was waked by Mr. Deming between 6 and 7 o. c. informing me that I was Gen. Gage’s prisoner all egress & regress being cut off between the town and the country. Here again description fails. No words can paint my distress—I feel it at this instant (just eight weeks after) so sensibly that I must pause before I proceed.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"An almost panoramic look at our history and culture through the eyes of American women."—Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

"A delightful collection of belles letters in the most literal sense of the term, and a worthy successor to the editors' previous volume [Letters of the Century]."—Publishers Weekly

"Whether as a rich primary source or simply an illuminating read, Women's Letters is.... sure to be required reading not just for devotees of women's history or the fine art of letter writing but also for surveying the broad scope of American history itself."—Library Journal

"These 400 letters chronicle the changes in women’s status even as their personal lives continue to revolve around family and friends, telling the stories of their lives and the life of the nation with incredible breadth and depth."—Booklist, starred review

"Women's Letters ranges far and wide, both across the country and across the landscape of experience.... Reading the personal, unfiltered words of so many women through the centuries spurs a much more intimate connection with the past—and a better understanding of it—than most college textbooks can. Too bad "Women's Letters" wasn't around when we were trudging across the dry terrain of American History 101."—Minneapolis Star Tribune

From the Hardcover edition.

"A delightful collection of belles letters in the most literal sense of the term, and a worthy successor to the editors' previous volume [Letters of the Century]."—Publishers Weekly

"Whether as a rich primary source or simply an illuminating read, Women's Letters is.... sure to be required reading not just for devotees of women's history or the fine art of letter writing but also for surveying the broad scope of American history itself."—Library Journal

"These 400 letters chronicle the changes in women’s status even as their personal lives continue to revolve around family and friends, telling the stories of their lives and the life of the nation with incredible breadth and depth."—Booklist, starred review

"Women's Letters ranges far and wide, both across the country and across the landscape of experience.... Reading the personal, unfiltered words of so many women through the centuries spurs a much more intimate connection with the past—and a better understanding of it—than most college textbooks can. Too bad "Women's Letters" wasn't around when we were trudging across the dry terrain of American History 101."—Minneapolis Star Tribune

From the Hardcover edition.