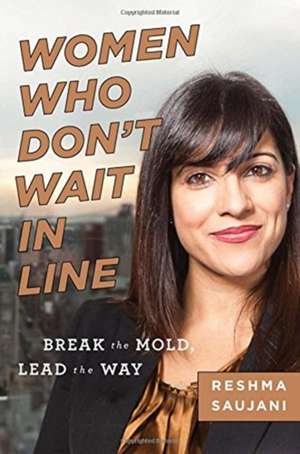

Women Who Don't Wait in Line: Break the Mold, Lead the Way

Autor Reshma Saujanien Limba Engleză Hardback – 7 oct 2013

Women Who Don’t Wait in Lineis an urgent wake-up call from politico and activist Reshma Saujani. The former New York City Deputy Public Advocate and founder of the national nonprofit Girls Who Code argues that aversion to risk and failure is the final hurdle holding women back in the workplace. Saujani advocates a new model of female leadership based on sponsorship—where women encourage each other to compete, take risks, embrace failure, and lift each other up personally and professionally.

Woven throughout the book are lessons and stories from accomplished women like Susan Lyne, Randi Zuckerberg, Mika Brzezinski, and Anne-Marie Slaughter, who have faced roadblocks and overcome them by forging new paths, being unapologetically ambitious, and never taking no for an answer. Readers are also offered a glimpse into Saujani’s personal story, including her immigrant upbringing and the insights she gleaned from running a spirited campaign for U.S. Congress in 2010.

Above all else,Women Who Don’t Wait in Lineis an inspiring call from a woman who is still deep in the trenches. Saujani aims to ignite her fellow women—and enlist them in remaking America.

Preț: 154.17 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 231

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.50€ • 32.04$ • 24.78£

29.50€ • 32.04$ • 24.78£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780544027787

ISBN-10: 0544027787

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: HMH Books

Colecția New Harvest

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0544027787

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: HMH Books

Colecția New Harvest

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

RESHMA

SAUJANI is

a

former

New

York

City

deputy

public

advocate

and

the

founder

of

Girls

Who

Code,

a

nonprofit

that

prepares

underserved

girls

for

careers

in

science

and

technology.

She

ran

for

U.S.

Congress

in

New

York’s

14th

District

as

a

Democrat

in

2010.

Extras

1

Fail Fast, Fail First, Fail Hard

In

January

2010,

when

I

officially

announced

my

decision

to

run

for

Congress,

so

many

years

after

first

having

dreamed

the

idea,

I

expected

to

feel

an

overwhelming

sense

of

relief

and

excitement.

Instead, to my surprise, I was racked with anxiety. Heart-pounding, ear-buzzing, stomach-churning anxiety. Often, as I was heading to important meetings, I’d find myself in a cold sweat.

Why, now that I was doing what I’d always wanted, was I feeling so panicked? It wasn’t that I questioned my own commitment — I wanted this job to make a difference more than anything. But nagging voices of self-doubt were echoing in my hand. Critics were charging that I was too young, too new, too different, too inexperienced. I got bogged down in how others saw me, and started losing sight of myself. What if I flubbed a policy question? Would I be dismissed as a lightweight? Did I have the chops, the smarts, the skills to handle this job?

In retrospect, my insecurities seem unwarranted. Sure, I was younger than my opponent — but, at thirty-four, hardly a fledgling. After all, there are numerous examples of even younger men who have been elected to the House of Representatives. For example, Aaron Schock, who at twenty-seven ran and won an election to represent Illinois’s Eighteenth Congressional District in 2009.

As for being a lightweight, I had a master’s degree in public policy from Harvard and a law degree from Yale. And I wasn’t a newbie to the political world: I had a decade of campaign experience working on presidential and local elections, and I had seen scores of candidates go through the firing squad of dense policy questions, so I knew what to expect. I’d been a civic activist, organizing young people and communities of color since I was thirteen years old. But in the moment, instead of focusing on all the things I knew that I knew, I stressed about what I didn’t know. Instead of feeling confident in who I was, I fretted about who — and what — I was not.

To manage my anxiety, I obsessed over my stump speech. The speech became a symbol of something I could control and perfect and use to mitigate my chances of losing the race. I convinced myself that if I could memorize the lines, and gracefully deliver each word, then somehow that polished performance would smooth over any perceived flaws. I spent hours in front of the computer, watching speech after speech on YouTube, trying to discern the secrets of great orators like Eleanor Roosevelt or Benazir Bhutto. I imagined delivering the speech in my head, over and over again. The perfect speech was going to become a stand-in for a perfect me.

On the day of a speech, I would pace up and down the length of my apartment, clutching the script, rehearsing my arguments before the empty room. Then, at game time, I would take a crumpled sheet of speech notes with me, keeping them at the podium, in a pocket, or in my purse, like Linus’s security blanket — a safeguard against the prospect that I might forget an important line.

My communications director kept scolding me for obsessing about memorization. “It isn’t how you say it,” he’d argue. “It’s what you have to say.” It took time for his words to sink in, but I finally came around.

By the end of the campaign trail, I had tossed the cheat sheet. No more trying to adhere to a faultless script. I spoke from the heart — about who I was, what I believed, and what I would do for my community if elected. I stopped trying to be perfect and just started to be me: all of me, even the part of me that occasionally fumbles words, trips over my tongue, or sometimes sounds inelegant. And I ultimately learned that having confidence in myself — believing that I was prepared enough, smart enough, and strong enough — was not only empowering, but it was also a self-fulfilling prophecy. I became these things. And confidence is also infectious, because that’s when my campaign took off. That’s when other people became passionately drawn to our call for change.

Instead, to my surprise, I was racked with anxiety. Heart-pounding, ear-buzzing, stomach-churning anxiety. Often, as I was heading to important meetings, I’d find myself in a cold sweat.

Why, now that I was doing what I’d always wanted, was I feeling so panicked? It wasn’t that I questioned my own commitment — I wanted this job to make a difference more than anything. But nagging voices of self-doubt were echoing in my hand. Critics were charging that I was too young, too new, too different, too inexperienced. I got bogged down in how others saw me, and started losing sight of myself. What if I flubbed a policy question? Would I be dismissed as a lightweight? Did I have the chops, the smarts, the skills to handle this job?

In retrospect, my insecurities seem unwarranted. Sure, I was younger than my opponent — but, at thirty-four, hardly a fledgling. After all, there are numerous examples of even younger men who have been elected to the House of Representatives. For example, Aaron Schock, who at twenty-seven ran and won an election to represent Illinois’s Eighteenth Congressional District in 2009.

As for being a lightweight, I had a master’s degree in public policy from Harvard and a law degree from Yale. And I wasn’t a newbie to the political world: I had a decade of campaign experience working on presidential and local elections, and I had seen scores of candidates go through the firing squad of dense policy questions, so I knew what to expect. I’d been a civic activist, organizing young people and communities of color since I was thirteen years old. But in the moment, instead of focusing on all the things I knew that I knew, I stressed about what I didn’t know. Instead of feeling confident in who I was, I fretted about who — and what — I was not.

To manage my anxiety, I obsessed over my stump speech. The speech became a symbol of something I could control and perfect and use to mitigate my chances of losing the race. I convinced myself that if I could memorize the lines, and gracefully deliver each word, then somehow that polished performance would smooth over any perceived flaws. I spent hours in front of the computer, watching speech after speech on YouTube, trying to discern the secrets of great orators like Eleanor Roosevelt or Benazir Bhutto. I imagined delivering the speech in my head, over and over again. The perfect speech was going to become a stand-in for a perfect me.

On the day of a speech, I would pace up and down the length of my apartment, clutching the script, rehearsing my arguments before the empty room. Then, at game time, I would take a crumpled sheet of speech notes with me, keeping them at the podium, in a pocket, or in my purse, like Linus’s security blanket — a safeguard against the prospect that I might forget an important line.

My communications director kept scolding me for obsessing about memorization. “It isn’t how you say it,” he’d argue. “It’s what you have to say.” It took time for his words to sink in, but I finally came around.

By the end of the campaign trail, I had tossed the cheat sheet. No more trying to adhere to a faultless script. I spoke from the heart — about who I was, what I believed, and what I would do for my community if elected. I stopped trying to be perfect and just started to be me: all of me, even the part of me that occasionally fumbles words, trips over my tongue, or sometimes sounds inelegant. And I ultimately learned that having confidence in myself — believing that I was prepared enough, smart enough, and strong enough — was not only empowering, but it was also a self-fulfilling prophecy. I became these things. And confidence is also infectious, because that’s when my campaign took off. That’s when other people became passionately drawn to our call for change.

Take the Leap

Women

tend

to

underestimate

their

own

abilities,

while

men

tend

to

overestimate

theirs.

This

phenomenon

even

affects

women

who

have

managed

to

overcome

their

insecurities,

taken

professional

risks,

and

are

at

the

height

of

their

careers.

Women are taught to be risk-averse. Starting at young age, we are taught to stay off the monkey bars, stay in the shallow end — with the result that too often, we prepare and prepare instead of boldly pursuing our dreams. Women take classes on everything from how to start a business to making investments, while men just forge ahead. Maybe that’s part of the reason why women seem stalled in the corporate hierarchy; why, even as there has been an explosion of women in management positions, so few are making it all the way to the top. And why, when women get to the top, they stay there, instead of taking even more risks to get to the next leadership level.

Take, for example, Virginia M. Rometty, who became CEO of IBM in January 2012. Rometty is outspoken about the importance of her willingness to take both personal and professional risks. She attributes her career success to “experiential” learning and her willingness to try to learn from new things. Nonetheless, theNew York Timesreported that when Rometty was offered the “big job,” she felt she lacked experience and would need time to consider the position.1

When she discussed the offer with her husband, he asked her, “Do you think a man would have ever answered that question that way?”

Rometty realized that not only was she qualified and ready for the job, but it was exactly the kind of challenge she needed to push herself even further. “People are their first worst critic, and it stops them from getting another experience,” she observed. It’s a vicious cycle: women give themselves more time to improve their skills, to gain one more qualification, and, as a result, they may pass up that promotion and the challenges that come with it, which is exactly what they need to grow professionally. According to Rometty, “Growth and comfort do not coexist.”2

Never hide. Learn by doing. I did not become a better speaker, and ultimately a better candidate, by waiting to ripen like fruit in a brown paper bag. I evolved by stepping out into the world and responding to the cues and feedback around me. I learned how to run for office by running for office. I learned how to be a compelling public speaker by speaking publicly. I evolved by taking big risks in pursuit of a big goal, knowing fully that I might fail.

Anxiety about whether we’re ready for the big challenge is a recurring theme and often leads women down the road of endless preparation, the pursuit of perfection, and the desire to prove we can do the job before we even dare to apply. My obsession with memorizing my stump speech fell into this category. I didn’t want to screw up or flub my first impression with voters. I was afraid that if I stumbled in my speech, the audience would conclude I wasn’t smart — and that, by the same token, a perfect delivery would be equated in their minds with a perfect candidate. So I practiced and practiced, rehearsed and rehearsed, and almost drove myself nuts in the process.

I’m not saying that women should be content with a subpar performance. But too often, the effect of holding ourselves to such high standards is that we forgo the chance to show our mettle at all. Either we hang back because we’re afraid we won’t excel, or we content ourselves with baby steps in our careers, instead of taking ambitious leaps.

This leads to the second issue that modern women must confront: getting comfortable with risk-taking.

There is a time to take risks and time to hedge your bets. For example, during the financial crisis, it was striking that there were no top female decision makers at any major Wall Street firm. It made me wonder, as many others did too: If Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters, would the company still be around today? If more women ran Wall Street, would the financial crisis have happened or been as catastrophic?

Evidence shows that this aversion to risk actually leads to higher investment returns when women are the ones making investment decisions. Professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean found that women’s portfolios outperform men’s portfolios by about 1 percent annually.3 Female investors trade in and out of stocks less frequently and avoid investment decisions that are more volatile.

That’s courage — and we need more of it. When our cautious instincts become intertwined with excessive doubt about our own abilities and qualifications, we are thwarting our potential and holding ourselves back from reaching new levels of success. It’s hard to win the race when women opt out before we even get to the starting line.

A few years ago I read a story about the GNOME Project, which designs free and open source software. The company advertised for a summer coding position and received almost two hundred applications — all of them from men. An observer might conclude that there simply weren’t any capable female programmers for the job. But the article went on to explain, “When GNOME advertised an identical program for women, emphasizing opportunities for learning and mentorship instead of tough competition, it received applications from more than 100 highly qualified females.”4

Anna Lewis, who wrote the article and also recruited talent for a private sector software company, recounted her surprise at learning from a female intern that the corporation’s slogan — “We Help the World’s Best Developers Make Better Software” — might alienate female candidates, because, as the intern put it, “when you hear the phrase ‘the world’s best developers,’ you see a guy.”5 How many times does this scenario play out — where capable women withdraw themselves from consideration for a position before they even apply?

There is an elephant in the room that we all need to get over: the fear of failure. No one likes failing — but women may take the prospect especially hard. Tiffany Dufu, an inspirational leader who ran the White House Project and is now the Chief Leadership Officer Levo League, credits her father with helping her overcome fear of failure from a very early age:

I got lots of practice very early doing a couple of things that are very challenging for women to do in terms of their leadership trajectory. One is I had to fail all the time publicly in front of people because if I wasn’t always going to win my student government election, I still had to come to school the next day having lost the race or lost the election.6

Of course, it’s too late for us to turn back the clock and run for elementary school student government, but there is much we can do to help one another assert the confidence to lead — and raise our daughters to trust their own voices, as Tiffany’s dad did with hers.

After all, the world’s most successful women have not achieved what they have achieved by avoiding failure. Many did not succeed the first, second, or even third time they tried for a big goal. But they kept at it, they kept pushing. Gertrude Stein submitted poem after poem for twenty years before one was accepted by a publication. Oprah Winfrey had a rocky start to her professional career and was fired for “being ‘unfit for TV.’”7 Marilyn Monroe was dropped from Twentieth Century–Fox one year into her contract and was told that she was not pretty and had no future in acting. Emily Dickinson had only a dozen of the more than eighteen hundred poems she wrote published during her lifetime. J. K. Rowling, the author of the bestselling book series Harry Potter, was a single mother living on welfare before her book was sold. Kathryn Stockett received sixty rejection letters for her novelThe Help. Lady Gaga got dropped by a label early in her career. The list goes on.

Women are taught to be risk-averse. Starting at young age, we are taught to stay off the monkey bars, stay in the shallow end — with the result that too often, we prepare and prepare instead of boldly pursuing our dreams. Women take classes on everything from how to start a business to making investments, while men just forge ahead. Maybe that’s part of the reason why women seem stalled in the corporate hierarchy; why, even as there has been an explosion of women in management positions, so few are making it all the way to the top. And why, when women get to the top, they stay there, instead of taking even more risks to get to the next leadership level.

Take, for example, Virginia M. Rometty, who became CEO of IBM in January 2012. Rometty is outspoken about the importance of her willingness to take both personal and professional risks. She attributes her career success to “experiential” learning and her willingness to try to learn from new things. Nonetheless, theNew York Timesreported that when Rometty was offered the “big job,” she felt she lacked experience and would need time to consider the position.1

When she discussed the offer with her husband, he asked her, “Do you think a man would have ever answered that question that way?”

Rometty realized that not only was she qualified and ready for the job, but it was exactly the kind of challenge she needed to push herself even further. “People are their first worst critic, and it stops them from getting another experience,” she observed. It’s a vicious cycle: women give themselves more time to improve their skills, to gain one more qualification, and, as a result, they may pass up that promotion and the challenges that come with it, which is exactly what they need to grow professionally. According to Rometty, “Growth and comfort do not coexist.”2

Never hide. Learn by doing. I did not become a better speaker, and ultimately a better candidate, by waiting to ripen like fruit in a brown paper bag. I evolved by stepping out into the world and responding to the cues and feedback around me. I learned how to run for office by running for office. I learned how to be a compelling public speaker by speaking publicly. I evolved by taking big risks in pursuit of a big goal, knowing fully that I might fail.

Anxiety about whether we’re ready for the big challenge is a recurring theme and often leads women down the road of endless preparation, the pursuit of perfection, and the desire to prove we can do the job before we even dare to apply. My obsession with memorizing my stump speech fell into this category. I didn’t want to screw up or flub my first impression with voters. I was afraid that if I stumbled in my speech, the audience would conclude I wasn’t smart — and that, by the same token, a perfect delivery would be equated in their minds with a perfect candidate. So I practiced and practiced, rehearsed and rehearsed, and almost drove myself nuts in the process.

I’m not saying that women should be content with a subpar performance. But too often, the effect of holding ourselves to such high standards is that we forgo the chance to show our mettle at all. Either we hang back because we’re afraid we won’t excel, or we content ourselves with baby steps in our careers, instead of taking ambitious leaps.

This leads to the second issue that modern women must confront: getting comfortable with risk-taking.

There is a time to take risks and time to hedge your bets. For example, during the financial crisis, it was striking that there were no top female decision makers at any major Wall Street firm. It made me wonder, as many others did too: If Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters, would the company still be around today? If more women ran Wall Street, would the financial crisis have happened or been as catastrophic?

Evidence shows that this aversion to risk actually leads to higher investment returns when women are the ones making investment decisions. Professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean found that women’s portfolios outperform men’s portfolios by about 1 percent annually.3 Female investors trade in and out of stocks less frequently and avoid investment decisions that are more volatile.

That’s courage — and we need more of it. When our cautious instincts become intertwined with excessive doubt about our own abilities and qualifications, we are thwarting our potential and holding ourselves back from reaching new levels of success. It’s hard to win the race when women opt out before we even get to the starting line.

A few years ago I read a story about the GNOME Project, which designs free and open source software. The company advertised for a summer coding position and received almost two hundred applications — all of them from men. An observer might conclude that there simply weren’t any capable female programmers for the job. But the article went on to explain, “When GNOME advertised an identical program for women, emphasizing opportunities for learning and mentorship instead of tough competition, it received applications from more than 100 highly qualified females.”4

Anna Lewis, who wrote the article and also recruited talent for a private sector software company, recounted her surprise at learning from a female intern that the corporation’s slogan — “We Help the World’s Best Developers Make Better Software” — might alienate female candidates, because, as the intern put it, “when you hear the phrase ‘the world’s best developers,’ you see a guy.”5 How many times does this scenario play out — where capable women withdraw themselves from consideration for a position before they even apply?

There is an elephant in the room that we all need to get over: the fear of failure. No one likes failing — but women may take the prospect especially hard. Tiffany Dufu, an inspirational leader who ran the White House Project and is now the Chief Leadership Officer Levo League, credits her father with helping her overcome fear of failure from a very early age:

I got lots of practice very early doing a couple of things that are very challenging for women to do in terms of their leadership trajectory. One is I had to fail all the time publicly in front of people because if I wasn’t always going to win my student government election, I still had to come to school the next day having lost the race or lost the election.6

Of course, it’s too late for us to turn back the clock and run for elementary school student government, but there is much we can do to help one another assert the confidence to lead — and raise our daughters to trust their own voices, as Tiffany’s dad did with hers.

After all, the world’s most successful women have not achieved what they have achieved by avoiding failure. Many did not succeed the first, second, or even third time they tried for a big goal. But they kept at it, they kept pushing. Gertrude Stein submitted poem after poem for twenty years before one was accepted by a publication. Oprah Winfrey had a rocky start to her professional career and was fired for “being ‘unfit for TV.’”7 Marilyn Monroe was dropped from Twentieth Century–Fox one year into her contract and was told that she was not pretty and had no future in acting. Emily Dickinson had only a dozen of the more than eighteen hundred poems she wrote published during her lifetime. J. K. Rowling, the author of the bestselling book series Harry Potter, was a single mother living on welfare before her book was sold. Kathryn Stockett received sixty rejection letters for her novelThe Help. Lady Gaga got dropped by a label early in her career. The list goes on.

Ladies, it’s time to stop worrying and start believing.

Everything you know and are is enough to snag that promotion; you are more capable than you give yourself credit for.

Never hide. Learn by doing.

Nothing wagered, nothing gained — it pays to take risks.

Get comfortable with failure. It’s a necessary part of progress.

Jump the Line

Throw a Failure Party

One of the best ways to bolster your confidence is to realize you’re not alone. The prospect of failure seems less scary when you know that women you admire have stumbled — or worse — and not just survived but thrived. So throw a Failure Party. Invite friends, colleagues, neighbors, people you admire to share the stories of their own mistakes. Ask all of your guests to prepare a two-minute story about their biggest failure to share with the room. Let’s get over our aversion to admitting or reflecting on failure. Truth-telling in this way is empowering.

It’s also refreshing. I mean, how many times have you heard panelists or presenters go on and on about all the things they got right without mentioning one thing about what they did wrong? It’s boring and unhelpful. Worse, half the time, those panels just make you feel bad about yourself.

The universal truth is that achieving success isn’t something that happens on a first try. It’s hard work for everyone. Women and men are failing around us all the time. As aspiring leaders, what we really want to know is how they ran their car off the track — and what they did to get back in the race.

To build an army of strong women we must be willing to admit our struggles to one another. Stephanie Harbour, the former president of Moms Corps NYC, sees failure as an opportunity to connect and support other women.

I really try to encourage young women that failure is okay — especially if you are the kind of woman who strives for excellence and almost always succeeds. You get into good schools. You do well at those schools. You get good jobs. And then you have a big failure and it can be absolutely devastating. Women fail silently a lot and suffer silently. [Instead,] we can help each other learn and be more open about those failures; that’s a huge area of opportunity for us to help pick each other up in pretty big ways.

Here’s the plan: Get a bunch of friends, colleagues, and mentors together for a meal and have a conversation about mistakes you’ve made and what you could have or should have done differently. Be vulnerable. Be honest. Let it all hang out. There is no shame in bearing your battle scars.

Angel investor and start-up adviser Joanne Wilson told a revealing story at the 2012 ITP’s Women Entrepreneurs Festival about how one of the women on the panel was asked a question about the first year of her business. Joanne said, “You hear from most entrepreneurs that everything is just great. There is this eternal optimism. The panelist said she pretty much cried every day of the first year. There was an audible sigh in the room.”8

I know the idea of celebrating failure may seem kind of weird. Talking about failure is emotionally unpleasant; reliving low moments — yours or anyone else’s — may not sound like how you want to spend a Saturday night. But some of the most innovative people in the world — scientists, entrepreneurs, inventors, designers — depend on this very approach. When they are looking at a product, they focus on the flaws. They know that sometimes, the biggest leaps forward begin with understanding what is wrong. We can learn a lot from being more scientific about our failures. We can stop fearing that big fat F word and start seeing failure as badge of courage and a springboard for professional growth.

In fact, several supporters declared that my loss in the New York congressional race was a blessing in disguise. I needed to experience failure in order to ultimately achieve my goals. I know now they were right.

Cuprins

Introduction xi

1. Fail Fast, Fail First, Fail Hard 1

2. Unapologetically Ambitious 21

3. Don’t Worry if They Don’t Like You 37

4. Follow Your Bliss 54

5. Be Authentic 66

6. Building a Sisterhood for the Twenty-First Century 86

7. Taking It to the Streets 103

Conclusion 128

Acknowledgments 131

Notes 136

Descriere

New

York

City

Deputy

Advocate

Reshma

Saujani

asks

why

women,

in

an

era

where

they

are

told

they

can

do

anything,

still

haven’t

joined

the

top

ranks

of

corporations

or

government.

Saujani

charts

the

paths

of

accomplished

women,

encouraging

all

women

to

take

risks,

compete,

embrace

failure,

and

build

support

through

a

twenty-first-century

sisterhood.