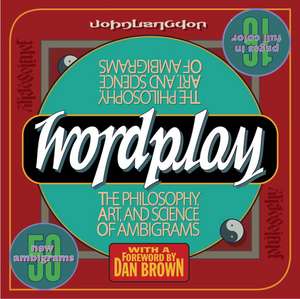

Wordplay: The Philosophy, Art, and Science of Ambigrams

Autor John Langdonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2005

You may be familiar with the John Langdon’s ambigrams from Dan Brown’s bestseller Angels & Demons (see pages 186 and 188 of Wordplay), but if this is your first experience with the art of the ambigram, prepare to be dazzled! This lovely updated edition of the classic collection of ambigrams features a section of full-color ambigrams and dozens of stunning, mind-bending examples of this cryptic art form. Each strikingly beautiful and arresting illustration is accompanied by a short essay—sometimes serious, sometimes witty—to delight your brain as much as your eyes. Taken together, the art and the essays show how the very shape of letters can change our idea of words and their meanings. As Dan Brown says in the Foreword of this revised edition, John Langdon brilliantly rearranges the familiar, casting it in a new light.

Both playful and profound, Wordplay will challenge you to take a second look at your world.

Preț: 112.94 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.61€ • 22.33$ • 17.98£

21.61€ • 22.33$ • 17.98£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 februarie-12 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767920759

ISBN-10: 0767920759

Pagini: 203

Ilustrații: 16 PAGE COLOR INSERT

Dimensiuni: 207 x 206 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767920759

Pagini: 203

Ilustrații: 16 PAGE COLOR INSERT

Dimensiuni: 207 x 206 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

Graphic designer JOHN LANGDON has won numerous awards for his logo designs; his ambigrams have appeared in countless publications; and the first museum show of his paintings was held in late 2004 at the Noyes Museum of Art in New Jersey.He is the creator of the ambigrams in Dan Brown’s Angels & Demons. Langdon teaches at the College of Media Arts & Design at Drexel University, and lives in Philadelphia.

Extras

Discovering the Tao

The first time I saw the yin and yang symbol was one of those moments that become permanent mental photographs. I didn't know back in 1966 what lay beyond the door, but it is now clear that a door had opened for me. Yin and yang made a deep and immediate impression--an impression I was aware of somewhere between my nervous system and the source of my emotions, but would have been hard pressed to identify or describe out loud. If I had said anything, I might have quoted the introduction to the 1960s TV program Ben Casey: "Man . . . woman . . . birth . . . death . . . infinity . . . ," followed perhaps by "summer, winter, hot, cold, north, south, on, off, up, down," and so on. Although it would be several years before I ever heard of Taoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy from which yin and yang originates, I seem to have subconsciously sensed that the symbol's simple representation of polarized opposites and harmonious complements applied perfectly to most of the major forces inherent in our existence.

I pondered the yin and yang symbol and fooled around with it graphically for years, at first unaware of the interest in Eastern thought that was to grow steadily in popularity through the ensuing decades. After seeing parts of this book in its early stages, a young physics student wrote to me: "Taoist imagery of interaction and of a natural, flowing, universal holism is becoming more and more infused into our consciousness. Such ideas have been a latent part of our psyche for centuries. Their lineage can be traced, almost directly, from the Renaissance hermeticists, to the alchemists and early scientists, through writers such as Eliot and Joyce, and finally into aspects of our own popular culture."

The sixties' pop culture included a significant amount of interest in Eastern thought, which has since filtered into many more mainstream facets of Western culture.

In the same way that the cross could be thought of as a logo for Christianity and the Star of David as a logo for Judaism, the yin and yang symbol is a logo for Taoism. As such, it is one of the best logos ever designed. A logo should communicate, in as simple and efficient a form as possible, a maximum of information about the entity it represents. And by the time I began to read about Taoism, I found to my amazement that I had already inferred virtually all that I was reading, simply by applying the ideas of polarized opposites and harmonious complements to a seemingly infinite number of situations that exist in our lives and in the workings of the universe. This, I learned, is quite appropriate to Taoism, a basic tenet of which holds that each person should find his own way. In the words of Lao-tzu, "Without leaving my house, I [can] know the whole universe."

It seems likely that Taoism developed in much the same way as the physical sciences did--through observation of the world around us. Sir Isaac Newton is perhaps best known for his third law, which states that "for every action, there is opposed an equal and opposite reaction." The yin and yang symbol may as well have been designed to illustrate that idea. In his letter to me, the physics student also said, "Science has directly encountered [the yin/yang] theme in the study of dynamical systems, popularly termed 'chaos theory.' Chaotic behavior . . . is dependent on a feedback mechanism, in which each of several factors interacts to determine the value of the others. It can be said that fractals are none other than microscopic images, resolvable to infinite but never ultimate detail, of the interaction between yin and yang." "Chaos" may not be the best name for this relatively new area of scientific study. The subjects of its interest have indeed appeared to be chaotic for centuries, but as they begin to be understood, they exhibit instead a different kind of order--one that has eluded classical scientific methods. Yin-and-yang-like relationships are beginning to emerge between, for example, order and disorder, and stability and instability.

I began to investigate other basic scientific principles and often found either visual representations of data, such as the "normal bell curve," or descriptions of visible physical phenomena, like wave patterns. For instance, not only does a path worn by a random sampling of a population walking across an open area of grass describe a "path" of least resistance, but its depression into the earth is virtually a normal distribution curve, albeit an inverted one, caused by the majority of people walking down the middle of it. The spiral is frequently found in patterns that nature creates, from the microscopic DNA helix, through snail shells and sunflowers, to galaxies thousands of light-years across. Often the shapes and proportions of these spirals mathematically follow the Fibonacci series: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, etc. Wavelengths seem similar to a series of normal distribution curves, and the infinity symbol could be seen as two normal bell curves curled around and linked to complete a circuit. They all seem graphically, philosophically, and scientifically related to one another and to the yin and yang symbol. They all appealed to me in the same way that yin and yang had--as simple and beautiful shapes that represented basic and powerful universal principles. Naturally, the names of these symbols and concepts became candidates for word designs that might illuminate the ideas they represent and demonstrate their relationships to the overriding yin and yang principle. And so they became ambigrams.

The yin/yang principle was, for many years, a dominant focus of my private thinking and my personal development. It has in recent years become less an object of my meditations, and more an underlying principle of how I see the world.

Yin and Yang

In the act of creation, a man brings together two facets of reality and, by discovering a likeness between them, makes them one.

Science and Human Values, Jacob Bronowski

Taoism is an ancient Chinese philosophy that is based on the observation that the universe is a dynamic system driven by the interplay of opposing and complementary forces.

The yin and yang symbol represents that system with elegant effectiveness. The black yin shape synthesizes the feminine principle: darkness, inwardness, yielding, and the unknown; the white yang represents the masculine principle: light, protrusion, aggressiveness, and the overt.

Since none of these characteristics could exist without its counterpart, each is necessarily an aspect of the other. To be more accurate, each yin and each yang is an integral aspect or part of a greater whole: "yinandyang"--or the Tao.

The Tao (pronounced "dow") can be an elusive concept. Indeed, the predominant piece of Taoist literature, the Tao Te Ching, begins with "The tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal Name." This seems to parallel imponderables and proscriptions in other spiritual traditions. We obviously need to acknowledge that there is something way, way beyond our ability to understand. The word Tao is perhaps best understood as "the way" or "the path." Those definitions can be thought of as meaning "the way" the universe works, and "the path" we would choose to live in harmony with the way of the universe around us.

Yin and yang looks fluid, and it is, in fact, quite flexible. Taking it to an extreme, but a thought-provoking point of view, philosopher Alan Watts said that at times he felt that he was yang and the entire rest of the universe was yin.

The shapes of the yin and the yang not only resemble droplets of liquid, but they aptly describe the ebb and flow of various fluid rhythms, in both time and space. As a pendulum changes its course when it has reached the extreme point of its swing in one direction, so yang begins at a tiny point where yin reaches its greatest width. Immediately following summer's "longest day of the year," the amount of daily darkness begins, imperceptibly perhaps, to move back toward winter. In other words, a characteristic symptom of winter can first be detected in midsummer. How far can you walk into the woods? Only halfway. After that, you're walking out.

Adjacent to the point where yang begins, in the middle of the maximum width of yin, is a dot of white. This signifies the idea that the very act of reaching a maximum point creates the seed (as it's often described) of an opposite reaction. It's as if, in its final push to expand to its maximum, yin has ruptured itself, creating a small gap. It's two centimeters dilated and about to give birth--to yang.

Another way of looking at this idea would demonstrate that in a complementary relationship between entities, the total elimination of one by the other is impossible. Because it is light that creates darkness, in the form of shadows, light cannot ever do away with all darkness. Unless perhaps someday--and it would be day!--all mass is converted to light energy. In a hypothetical relationship, with one species feeding only on one other, it would be impossible for the predator species to devour all of its prey. As the population of the prey dwindled to the point where the members of the predator species could not all be fed, the predators would begin to die off. The trend would reverse, and soon the population of the prey species could begin to increase. An all-andnothing relationship can be approached, but yin and yang's natural tendency toward balance prevents it from being achieved.

While the complementary "halves" of such relationships may not always appear to be equal, eventually most of them do turn out that way. Day and night are equal amounts of time only twice a year, at the equinoxes. But over the course of a year, every place on earth has day and night half of the time. Seeing Taoist balance often requires that the viewer step back, in either space or time, and take a longer view.

Yin and yang can function as a graph in which such complementary relationships are described. Much of the time the complementary opposites exist in a dominant and subordinate relationship. But yin and yang is never static.

Sociological research may show a majority point of view continuing to grow in popularity, but eventually the human instinct for individuality will react and a countermovement will arise. The social upheaval of the sixties was in direct response not only to the Vietnam War, the overt oppression of African-Americans, and the thinly veiled oppression of women, but also to the widespread acceptance of the fifties' postwar values. Conformity, convenience, and anticommunism were stretched so far over all aspects of American society that they became shallow and transparent. The larger the balloon grows, the more vulnerable it becomes. Oppression always breeds rebellion. So natural is this instinct that for the most part, things tend not to shift to extremes. The need for relative stability and balance usually keeps things hovering in a range near the center, but the greater the trend in one direction, the more extreme the response will be.

Yin and yang represents nature's ability to keep things in balance in a constantly shifting process of give and take.

Philosophy, Art, & Science

The search for truth will continue as long as there are human beings with curiosity. It will be pursued forever and never attained. This is due to the attitudes and working processes of those whose mission it is to define truth: philosophers, artists, and scientists.

The processes of philosophy require that strict logic be adhered to, and that conventions of argument be followed. For example, if A is true, then it must follow that B is also true. Or since A and B are true, then C cannot be true. A philosophical idea must be supported by logic and is likely to be subjected to challenge from another logical construct, another point of view. In general, philosophers do not attempt to establish immutable truths. Philosophers gain respect and gather adherents, knowing full well that they may, in time, lose both. The field seems to accept that there will always be another person with a new approach to "The Truth." The word philosophy does not mean a love of, or a knowledge of, truth. Rather it means "a love of wisdom"--having the capacity to ponder truths. In other words, it's not whether you win or lose, it's how smart a game you play.

The root of the word science, on the other hand, is the Latin word "to know." Historically, science has tried to reach conclusions. But the standards for acceptance are much more rigorous. Scientists attempt to ascertain their truths through hypothesis, experiment, deduction, and proof. A hypothesis often meets its ultimate test in the practice of disproof. It may be supported by any number of experiments, but if it can be disproved as well, it cannot be thought of as a truth, no matter how logical it may seem.

When a hypothesis has been proved and cannot be disproved, it may be thought of as being true, for the time being, at least. Strong hypotheses, supported by successful experiments, can build a "theory"--an interlocking set of laws that explain certain phenomena. When verified, hypotheses become theories--and are accepted as "provisionally true." Einstein's hypotheses regarding space and time have been borne out many times in the past several decades, so they have become known as "The Theory of Relativity." But science is always willing to replace "truths" with newer "truths."

Testing each new "truth" exposes new information, which raises new questions, and thereby engenders new hypotheses. With the demands made upon scientific process and the acceptance that truths may be only temporary, we see once again that Ultimate Truths are something of a Holy Grail--a carrot at the end of the stick. As Jacob Bronowski says, in Science and Human Values, "Science is not a mechanism but a human progress, and not a set of findings but the search for them."

Completing the equilateral triangle of truth seekers are the artists. Bronowski goes on: "The creative act is alike in art as in science; but it cannot be identical in the two; there must be a difference as well as a likeness . . . the artist in his creation surely has open to him a dimension of freedom which is closed to the scientist." Whereas philosophers are guided and constrained by logic, and scientists are careful to use strict controls to assure the accuracy of their data and findings, artists are free to approach truths by any path with no expectation of following what was done before. Artists can hardly expect not to follow, as it is too late to precede, but they try not to be led, at least. They often proceed by way of a synthesizing process, looking not to the recent past but to a more distant antecedent to blend with their own very current ideas. Thus the viewer looks at something familiar in a completely different way. This is the case with the ambigrams in this book: they pull together ancient philosophies, traditional science, and unorthodox lettering design. Their goal is to engender a new point of view toward words that may have long been familiar.

The first time I saw the yin and yang symbol was one of those moments that become permanent mental photographs. I didn't know back in 1966 what lay beyond the door, but it is now clear that a door had opened for me. Yin and yang made a deep and immediate impression--an impression I was aware of somewhere between my nervous system and the source of my emotions, but would have been hard pressed to identify or describe out loud. If I had said anything, I might have quoted the introduction to the 1960s TV program Ben Casey: "Man . . . woman . . . birth . . . death . . . infinity . . . ," followed perhaps by "summer, winter, hot, cold, north, south, on, off, up, down," and so on. Although it would be several years before I ever heard of Taoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy from which yin and yang originates, I seem to have subconsciously sensed that the symbol's simple representation of polarized opposites and harmonious complements applied perfectly to most of the major forces inherent in our existence.

I pondered the yin and yang symbol and fooled around with it graphically for years, at first unaware of the interest in Eastern thought that was to grow steadily in popularity through the ensuing decades. After seeing parts of this book in its early stages, a young physics student wrote to me: "Taoist imagery of interaction and of a natural, flowing, universal holism is becoming more and more infused into our consciousness. Such ideas have been a latent part of our psyche for centuries. Their lineage can be traced, almost directly, from the Renaissance hermeticists, to the alchemists and early scientists, through writers such as Eliot and Joyce, and finally into aspects of our own popular culture."

The sixties' pop culture included a significant amount of interest in Eastern thought, which has since filtered into many more mainstream facets of Western culture.

In the same way that the cross could be thought of as a logo for Christianity and the Star of David as a logo for Judaism, the yin and yang symbol is a logo for Taoism. As such, it is one of the best logos ever designed. A logo should communicate, in as simple and efficient a form as possible, a maximum of information about the entity it represents. And by the time I began to read about Taoism, I found to my amazement that I had already inferred virtually all that I was reading, simply by applying the ideas of polarized opposites and harmonious complements to a seemingly infinite number of situations that exist in our lives and in the workings of the universe. This, I learned, is quite appropriate to Taoism, a basic tenet of which holds that each person should find his own way. In the words of Lao-tzu, "Without leaving my house, I [can] know the whole universe."

It seems likely that Taoism developed in much the same way as the physical sciences did--through observation of the world around us. Sir Isaac Newton is perhaps best known for his third law, which states that "for every action, there is opposed an equal and opposite reaction." The yin and yang symbol may as well have been designed to illustrate that idea. In his letter to me, the physics student also said, "Science has directly encountered [the yin/yang] theme in the study of dynamical systems, popularly termed 'chaos theory.' Chaotic behavior . . . is dependent on a feedback mechanism, in which each of several factors interacts to determine the value of the others. It can be said that fractals are none other than microscopic images, resolvable to infinite but never ultimate detail, of the interaction between yin and yang." "Chaos" may not be the best name for this relatively new area of scientific study. The subjects of its interest have indeed appeared to be chaotic for centuries, but as they begin to be understood, they exhibit instead a different kind of order--one that has eluded classical scientific methods. Yin-and-yang-like relationships are beginning to emerge between, for example, order and disorder, and stability and instability.

I began to investigate other basic scientific principles and often found either visual representations of data, such as the "normal bell curve," or descriptions of visible physical phenomena, like wave patterns. For instance, not only does a path worn by a random sampling of a population walking across an open area of grass describe a "path" of least resistance, but its depression into the earth is virtually a normal distribution curve, albeit an inverted one, caused by the majority of people walking down the middle of it. The spiral is frequently found in patterns that nature creates, from the microscopic DNA helix, through snail shells and sunflowers, to galaxies thousands of light-years across. Often the shapes and proportions of these spirals mathematically follow the Fibonacci series: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, etc. Wavelengths seem similar to a series of normal distribution curves, and the infinity symbol could be seen as two normal bell curves curled around and linked to complete a circuit. They all seem graphically, philosophically, and scientifically related to one another and to the yin and yang symbol. They all appealed to me in the same way that yin and yang had--as simple and beautiful shapes that represented basic and powerful universal principles. Naturally, the names of these symbols and concepts became candidates for word designs that might illuminate the ideas they represent and demonstrate their relationships to the overriding yin and yang principle. And so they became ambigrams.

The yin/yang principle was, for many years, a dominant focus of my private thinking and my personal development. It has in recent years become less an object of my meditations, and more an underlying principle of how I see the world.

Yin and Yang

In the act of creation, a man brings together two facets of reality and, by discovering a likeness between them, makes them one.

Science and Human Values, Jacob Bronowski

Taoism is an ancient Chinese philosophy that is based on the observation that the universe is a dynamic system driven by the interplay of opposing and complementary forces.

The yin and yang symbol represents that system with elegant effectiveness. The black yin shape synthesizes the feminine principle: darkness, inwardness, yielding, and the unknown; the white yang represents the masculine principle: light, protrusion, aggressiveness, and the overt.

Since none of these characteristics could exist without its counterpart, each is necessarily an aspect of the other. To be more accurate, each yin and each yang is an integral aspect or part of a greater whole: "yinandyang"--or the Tao.

The Tao (pronounced "dow") can be an elusive concept. Indeed, the predominant piece of Taoist literature, the Tao Te Ching, begins with "The tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal Name." This seems to parallel imponderables and proscriptions in other spiritual traditions. We obviously need to acknowledge that there is something way, way beyond our ability to understand. The word Tao is perhaps best understood as "the way" or "the path." Those definitions can be thought of as meaning "the way" the universe works, and "the path" we would choose to live in harmony with the way of the universe around us.

Yin and yang looks fluid, and it is, in fact, quite flexible. Taking it to an extreme, but a thought-provoking point of view, philosopher Alan Watts said that at times he felt that he was yang and the entire rest of the universe was yin.

The shapes of the yin and the yang not only resemble droplets of liquid, but they aptly describe the ebb and flow of various fluid rhythms, in both time and space. As a pendulum changes its course when it has reached the extreme point of its swing in one direction, so yang begins at a tiny point where yin reaches its greatest width. Immediately following summer's "longest day of the year," the amount of daily darkness begins, imperceptibly perhaps, to move back toward winter. In other words, a characteristic symptom of winter can first be detected in midsummer. How far can you walk into the woods? Only halfway. After that, you're walking out.

Adjacent to the point where yang begins, in the middle of the maximum width of yin, is a dot of white. This signifies the idea that the very act of reaching a maximum point creates the seed (as it's often described) of an opposite reaction. It's as if, in its final push to expand to its maximum, yin has ruptured itself, creating a small gap. It's two centimeters dilated and about to give birth--to yang.

Another way of looking at this idea would demonstrate that in a complementary relationship between entities, the total elimination of one by the other is impossible. Because it is light that creates darkness, in the form of shadows, light cannot ever do away with all darkness. Unless perhaps someday--and it would be day!--all mass is converted to light energy. In a hypothetical relationship, with one species feeding only on one other, it would be impossible for the predator species to devour all of its prey. As the population of the prey dwindled to the point where the members of the predator species could not all be fed, the predators would begin to die off. The trend would reverse, and soon the population of the prey species could begin to increase. An all-andnothing relationship can be approached, but yin and yang's natural tendency toward balance prevents it from being achieved.

While the complementary "halves" of such relationships may not always appear to be equal, eventually most of them do turn out that way. Day and night are equal amounts of time only twice a year, at the equinoxes. But over the course of a year, every place on earth has day and night half of the time. Seeing Taoist balance often requires that the viewer step back, in either space or time, and take a longer view.

Yin and yang can function as a graph in which such complementary relationships are described. Much of the time the complementary opposites exist in a dominant and subordinate relationship. But yin and yang is never static.

Sociological research may show a majority point of view continuing to grow in popularity, but eventually the human instinct for individuality will react and a countermovement will arise. The social upheaval of the sixties was in direct response not only to the Vietnam War, the overt oppression of African-Americans, and the thinly veiled oppression of women, but also to the widespread acceptance of the fifties' postwar values. Conformity, convenience, and anticommunism were stretched so far over all aspects of American society that they became shallow and transparent. The larger the balloon grows, the more vulnerable it becomes. Oppression always breeds rebellion. So natural is this instinct that for the most part, things tend not to shift to extremes. The need for relative stability and balance usually keeps things hovering in a range near the center, but the greater the trend in one direction, the more extreme the response will be.

Yin and yang represents nature's ability to keep things in balance in a constantly shifting process of give and take.

Philosophy, Art, & Science

The search for truth will continue as long as there are human beings with curiosity. It will be pursued forever and never attained. This is due to the attitudes and working processes of those whose mission it is to define truth: philosophers, artists, and scientists.

The processes of philosophy require that strict logic be adhered to, and that conventions of argument be followed. For example, if A is true, then it must follow that B is also true. Or since A and B are true, then C cannot be true. A philosophical idea must be supported by logic and is likely to be subjected to challenge from another logical construct, another point of view. In general, philosophers do not attempt to establish immutable truths. Philosophers gain respect and gather adherents, knowing full well that they may, in time, lose both. The field seems to accept that there will always be another person with a new approach to "The Truth." The word philosophy does not mean a love of, or a knowledge of, truth. Rather it means "a love of wisdom"--having the capacity to ponder truths. In other words, it's not whether you win or lose, it's how smart a game you play.

The root of the word science, on the other hand, is the Latin word "to know." Historically, science has tried to reach conclusions. But the standards for acceptance are much more rigorous. Scientists attempt to ascertain their truths through hypothesis, experiment, deduction, and proof. A hypothesis often meets its ultimate test in the practice of disproof. It may be supported by any number of experiments, but if it can be disproved as well, it cannot be thought of as a truth, no matter how logical it may seem.

When a hypothesis has been proved and cannot be disproved, it may be thought of as being true, for the time being, at least. Strong hypotheses, supported by successful experiments, can build a "theory"--an interlocking set of laws that explain certain phenomena. When verified, hypotheses become theories--and are accepted as "provisionally true." Einstein's hypotheses regarding space and time have been borne out many times in the past several decades, so they have become known as "The Theory of Relativity." But science is always willing to replace "truths" with newer "truths."

Testing each new "truth" exposes new information, which raises new questions, and thereby engenders new hypotheses. With the demands made upon scientific process and the acceptance that truths may be only temporary, we see once again that Ultimate Truths are something of a Holy Grail--a carrot at the end of the stick. As Jacob Bronowski says, in Science and Human Values, "Science is not a mechanism but a human progress, and not a set of findings but the search for them."

Completing the equilateral triangle of truth seekers are the artists. Bronowski goes on: "The creative act is alike in art as in science; but it cannot be identical in the two; there must be a difference as well as a likeness . . . the artist in his creation surely has open to him a dimension of freedom which is closed to the scientist." Whereas philosophers are guided and constrained by logic, and scientists are careful to use strict controls to assure the accuracy of their data and findings, artists are free to approach truths by any path with no expectation of following what was done before. Artists can hardly expect not to follow, as it is too late to precede, but they try not to be led, at least. They often proceed by way of a synthesizing process, looking not to the recent past but to a more distant antecedent to blend with their own very current ideas. Thus the viewer looks at something familiar in a completely different way. This is the case with the ambigrams in this book: they pull together ancient philosophies, traditional science, and unorthodox lettering design. Their goal is to engender a new point of view toward words that may have long been familiar.

Descriere

Award-winning graphic designer John Langdon was perhaps the first practitioner of the art of ambigrams. In this updated edition he adds a significant amount of new material to further enhance the reader's enjoyment of the peculiar illusion created when a word can be read right-side up and upside down.