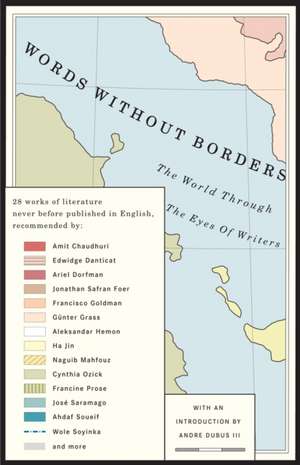

Words Without Borders: An Anthology

Editat de Samantha Schnee, Alane Salierno Mason, Dedi Felmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2007

In these pages, some of the most accomplished writers in world literature–among them Edwidge Danticat, Ha Jin, Cynthia Ozick, Javier Marias, and Nobel laureates Wole Soyinka, Günter Grass, Czeslaw Milosz, Wislawa Szymborska, and Naguib Mahfouz–have stepped forward to introduce us to dazzling literary talents virtually unknown to readers of English. Most of their work–short stories, poems, essays, and excerpts from novels–appears here in English for the first time.

The Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman introduces us to a story of extraordinary poise and spiritual intelligence by the Argentinian writer Juan Forn. The Romanian writer Norman Manea shares with us the sexy, sinister, and thrillingly avant garde fiction of his homeland’s leading female novelist. The Indian writer Amit Chaudhuri spotlights the Bengali writer Parashuram, whose hilarious comedy of manners imagines what might have happened if Britain had been colonized by Bengal. And Roberto Calasso writes admiringly of his fellow Italian Giorgio Manganelli, whose piece celebrates the Indian city of Madurai.

Every piece here–be it from the Americas, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, or the Caribbean–is a discovery, a colorful thread in a global weave of literary exchange.

Edited by Samantha Schnee, Alane Salierno Mason, and Dedi Felman

Preț: 118.78 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 178

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.75€ • 23.44$ • 19.06£

22.75€ • 23.44$ • 19.06£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400079759

ISBN-10: 1400079756

Pagini: 367

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400079756

Pagini: 367

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

ALANE SALIERNO MASON is a senior editor at W. W. Norton & Company. She lives in New York City.

DEDI FELMAN is a senior editor at Oxford University Press. She lives in Princeton, New Jersey.

SAMANTHA SCHNEE is the former senior editor of Zoetrope: All-Story. She lives in Houston, Texas.

All three are editors at WORDS WITHOUT BORDERS (WWB), the online magazine for international literature (www.wordswithoutborders.org). A partner of PEN American Center, WWB is hosted by Columbia University and Bard College and funded by the National Endowment for the Arts.

DEDI FELMAN is a senior editor at Oxford University Press. She lives in Princeton, New Jersey.

SAMANTHA SCHNEE is the former senior editor of Zoetrope: All-Story. She lives in Houston, Texas.

All three are editors at WORDS WITHOUT BORDERS (WWB), the online magazine for international literature (www.wordswithoutborders.org). A partner of PEN American Center, WWB is hosted by Columbia University and Bard College and funded by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Extras

MA JIAN

A sign painted on the wall of the hospital cafeteria reads: PRACTICE

REVOLUTIONARY HUMANISM. But the hospital won't care for those who can't pay for care; it leaves them begging at its gates. The crowds gawk, but don't intervene. Parents of those in need of help are helpless. What's left?

Ma Jian is impossible to classify. He writes politically, but he isn't a political writer. He employs surrealism without being a surrealist. Is he a comic nihilist? A tragic comedian? Ferocious? Generous? All and none, he explodes any title you might try to apply to him.

Except, perhaps, for "revolutionary humanist."

This story about a hospital is a hospital. A good, humane hospital, a revolutionary hospital that doesn't look like anything that came before it. But its characters aren't its patients. Its readers are.

Where are you running to? Characters in this story are running to different places--some to their pasts, some to their futures. Some are running to ideas of themselves, some to ideas that don't include people.

Readers are always running toward the same place when they open a book. We're trying to get to a greater understanding of ourselves. Books have no burden to entertain. Television and film and music are entertaining enough. Books don't need to be political or surreal or comic or tragic. They need to help us understand ourselves. Everything else a book does is incidental to that.

Writers are all running, too. They're running to meet their readers.

--JONATHAN SAFRAN FOER

WHERE ARE YOU RUNNING TO?

"Where are you running to?" shouts Zhao Chunyu, chairwoman of the local neighborhood committee, as she stands in the entrance to the staff accommodation block.

She's wearing cotton trousers and a tracksuit top that's faded to the color of old bricks. Her freshly washed hair, which was cut by her husband, Old Liu, and that's just been washed, is fluffing out in all directions, making her round face look even larger and her narrow eyes even smaller. At the moment, however, these small eyes are popping with rage; her arms are tightly folded across her chest, and a smell of raw celery is escaping from her mouth. A few minutes ago, she was chopping up vegetables for dinner. Old Liu walked in and, without washing his hands, broke off a stick of celery to have with his beer. Chunyu popped a piece into her mouth as well, and as they munched away, their son, Kai, leaped from his stool and rushed out of the door. Chunyu moved the bowl of celery onto the piano, out of Old Liu's reach, then followed her son downstairs.

"Where are you running to?" she shouts again.

"I don't want to play 'Pleading Child.' I hate slow pieces!"

"Well you can play 'Perfectly Contented' instead!"

"No, I won't play anything by Schumann! I refuse!"

"All right then. Tonight you can practice Chopin's Revolutionary Etude for a couple of hours. It's very fast, and it has that passage you like so much where the left hand plays in octaves."

"No, I won't play it! I won't!" Kai is shouting so loudly everyone in the block can hear. One wouldn't expect a ten-year-old child to be capable of producing such a noise.

"Come back here!" As Chunyu jumps down the two concrete steps below the entrance, Kai grabs on to a small willow tree that's just been planted, swings around in a half circle, then shoots off like a bullet down a small alleyway.

Chunyu hesitates for a while. Above her, she can hear her neighbor Old Jia saying to Old Zun, who lives on the third floor, "If Kai doesn't get into music school this time, he's had it. Next year he'll be too old."

"He's always playing the same pieces," Old Zun replies. "I know them by heart." Then he shouts down to Chunyu, "Your piano's sounding terrible these days! You should pay someone to come and tune it."

Chunyu ignores the men's remarks. She and her husband spent every last yuan they owned to buy that piano. Chunyu hasn't always been so poor--she was born into a wealthy family. When the Communists liberated China in 1949, she cut herself off from her parents and took active steps to join the party. As a result, she was able to secure a place at Beijing's Central Academy of Music. Unfortunately, just before she was due to graduate, an officer discovered an old photograph she'd been hiding that showed her playing the piano to a group of her parents' bourgeois friends. She was consequently labeled a rightist, and as Old Liu, who was her boyfriend at the time, refused to denounce her, they were both sent to a labor camp in the remote northwest where they remained for twenty-four years.

Chunyu scrapes back her hair and runs down the alleyway in pursuit of her son, shouting, "Come back, you little beast!"

In the light of the setting sun, she sees Kai swooping down the alley like a cockerel in flight. She steps up her speed. Since she isn't wearing socks, her feet grip well to her rubber-soled shoes. She feels as though she has the wind under her feet.

When she was eighteen, after a year of running more than ten kilometers a day from her Beijing lodgings to the Academy of Music and back, she became champion of the academy's annual long-distance race. Although she's now fifty-three years old, her legs are still strong. Last month she managed to chase after and catch a thief who'd stolen a tape recorder while wandering around her block pretending to deliver leaflets on a new brand of lipstick.

"Come back. If you don't stop, I'll kill you!"

Her son is wearing his school uniform: a white cotton suit with blue piping along the seams. His red necktie is as bright as a cockscomb. He pumps his arms as he runs. Chunyu is convinced that as long as she maintains her speed, she'll be able to catch him in less than twenty seconds. But she soon realizes that she can't match his pace, just as a duck can never match the pace of a chicken. She suspects that she's put on weight again. She's been concerned about her weight for the last ten years, ever since she and Old Liu were rehabilitated in 1981, and released from the labor camp. As soon as had she returned home, and arranged for a family portrait to be taken in a photographer's studio to celebrate the event, than her body started to balloon. As an adolescent, Chunyu was one of the prettiest girls in the town. Whenever she walked down the street, men would stop and gawk. But when she returned from the camp, her face looked so old that no one recognized her.

The little rascal who's running in front of her now was just three months old when the family portrait was taken. Chunyu was just forty-three, and still had a lot of life left to devote to the party and to herself. Within a few months, Old Liu's party membership was reinstated and he was assigned a post in the political office of a coal processing plant. Chunyu was appointed cultural officer of the Municipal Music Association, a post she held for nine years, until last year when she was promoted to chairwoman of the local neighborhood committee.

Back in 1981, her daughter, Xin, who was twelve years old, was preparing to take the entrance exam to the local music school. Chunyu had the key to the Music Association's piano room. During the day, she used the piano for teaching purposes, and let Xin practice on it in the evening. Chunyu bought all the sheet music that her daughter needed, and charged it to the Music Association. The family was now well provided for, and had a goal to work toward. Everything seemed to be going well. In 1983, Chunyu and Old Liu received eight thousand yuan in compensation for the years they spent in the labor camp. After Liu paid the 260-yuan party membership fee, they had just enough left over to order a small upright piano, which was delivered to them a year later. As life became easier following the implementation of the Open Door Policy, Chunyu's spirits improved, and so did her appetite. But, unlike Old Liu, she liked to keep active. Every day, she'd get up at dawn and hold dance classes outside the Open Door Club. She wanted to retrieve all the lost years of her youth, and was determined to keep her weight down to under seventy-five kilos. But she needn't have worried, because since Xin became ill six years ago, and then died two years later, Chunyu hasn't put on a gram of weight.

Her legs are now aching from the sudden sprint she made a few minutes ago. She's worried that her left kneecap has become dislodged. She watches her son swerve to the right and scurry down Construction Alley. That's where his school is.

"I bet he's going to jump over the school wall," she thinks to herself. "The little terror. He knows that I'm afraid of heights. I get vertigo just walking downstairs." When Chunyu was six years old, she once jumped off the balcony of her parents' apartment to avoid having to play the piano to her mother's friends. By then she could already play Beethoven's "Fur Elise" and Mendelssohn's "Spring Song" by heart. She injured herself so badly in the fall that she had to stay at home for three months. When she returned to school she was unable to catch up with the other children, so her parents decided to send her to a private music school instead, where she could concentrate on the piano.

"What's the hurry?" cries a friend of Old Liu's as Chunyu dashes past.

"Kai's trying to run away!" Chunyu shouts back, without turning around. It occurs to her that when her son was younger she didn't pay enough attention to him. She focused all of her energy on Xin. She was convinced that as long as Xin followed the practice plan that she'd devised, she would easily get a place at Beijing's Central Academy of Music. Xin looked just like Chunyu did as a young girl, but was even more talented. In the labor camp, when Xin saw a piano for the first time, in the film of the model play The Red Lantern, she immediately announced that she wanted to be a pianist when she grew up. Chunyu drew the notes of a keyboard along the edge of their brick bed, and within a few days, Xin was able to tap out the notes for the song "Nothing is redder than the sun, and no one is dearer to us than Chairman Mao Zedong." Xin's musical talent gave Chunyu a sense of purpose. She was determined that her daughter would become a great pianist, and succeed where she herself had failed.

But Chunyu could never have guessed that just four years after the family was released from the labor camp, her daughter would develop bone cancer. Xin was admitted to the hospital, and for the first two years, Chunyu's work unit paid for all the medical costs. But when Xin reached the age of eighteen, the payments came to an end. Without medical treatment, Xin's condition deteriorated drastically. The chief surgeon, Dr. Han, told Chunyu that Xin needed an emergency operation, and before this could take place, the hospital would require a payment of 40,000 yuan.

This sum was the equivalent of five years of Chunyu's and Old Liu's combined incomes. After a long discussion, the couple decided that Old Liu should take early retirement. From this he would gain a onetime pension award of 20,000 yuan. They calculated that they could then get 9,000 yuan from selling their piano and fridge, and borrow another 2,000 from close friends, which would give them a total of 31,000 yuan--just 9,000 yuan short of the sum the hospital demanded.

Through a backdoor connection, the couple asked an acquaintance to give the hospital director two bottles of French wine and two gift-wrapped jars of Nescafe and Coffee-mate. After accepting this bribe, the director agreed that Xin's operation could go ahead immediately, and gave the couple two weeks to pay the remaining 9,000 yuan. Xin underwent surgery the next day. After the operation, Dr. Han informed the couple that although the tumor had been successfully excised from Xin's pelvic bone, the cancer had spread to her stomach, and that she would now need a course of chemotherapy. For this additional treatment, the hospital required a further 10,000 yuan.

In an effort to start raising the money, Old Liu bought a wooden handcart and wheeled it around town looking for work. Many buildings were being demolished at the time, so there was plenty of work to be found. Old Liu could make forty or fifty yuan a day carting rubble from building sites to rubbish tips. Two weeks later, Old Liu handed the hospital the few hundred yuan that he'd made, and promised to pay the rest of the money as soon as he could. The director of the hospital told him that this money would cover only one more dose of anti-inflammatory drugs, and that once this was administered, his daughter would have to leave the hospital. Chunyu was devastated.

A sign painted on the wall of the hospital cafeteria reads: PRACTICE

REVOLUTIONARY HUMANISM. But the hospital won't care for those who can't pay for care; it leaves them begging at its gates. The crowds gawk, but don't intervene. Parents of those in need of help are helpless. What's left?

Ma Jian is impossible to classify. He writes politically, but he isn't a political writer. He employs surrealism without being a surrealist. Is he a comic nihilist? A tragic comedian? Ferocious? Generous? All and none, he explodes any title you might try to apply to him.

Except, perhaps, for "revolutionary humanist."

This story about a hospital is a hospital. A good, humane hospital, a revolutionary hospital that doesn't look like anything that came before it. But its characters aren't its patients. Its readers are.

Where are you running to? Characters in this story are running to different places--some to their pasts, some to their futures. Some are running to ideas of themselves, some to ideas that don't include people.

Readers are always running toward the same place when they open a book. We're trying to get to a greater understanding of ourselves. Books have no burden to entertain. Television and film and music are entertaining enough. Books don't need to be political or surreal or comic or tragic. They need to help us understand ourselves. Everything else a book does is incidental to that.

Writers are all running, too. They're running to meet their readers.

--JONATHAN SAFRAN FOER

WHERE ARE YOU RUNNING TO?

"Where are you running to?" shouts Zhao Chunyu, chairwoman of the local neighborhood committee, as she stands in the entrance to the staff accommodation block.

She's wearing cotton trousers and a tracksuit top that's faded to the color of old bricks. Her freshly washed hair, which was cut by her husband, Old Liu, and that's just been washed, is fluffing out in all directions, making her round face look even larger and her narrow eyes even smaller. At the moment, however, these small eyes are popping with rage; her arms are tightly folded across her chest, and a smell of raw celery is escaping from her mouth. A few minutes ago, she was chopping up vegetables for dinner. Old Liu walked in and, without washing his hands, broke off a stick of celery to have with his beer. Chunyu popped a piece into her mouth as well, and as they munched away, their son, Kai, leaped from his stool and rushed out of the door. Chunyu moved the bowl of celery onto the piano, out of Old Liu's reach, then followed her son downstairs.

"Where are you running to?" she shouts again.

"I don't want to play 'Pleading Child.' I hate slow pieces!"

"Well you can play 'Perfectly Contented' instead!"

"No, I won't play anything by Schumann! I refuse!"

"All right then. Tonight you can practice Chopin's Revolutionary Etude for a couple of hours. It's very fast, and it has that passage you like so much where the left hand plays in octaves."

"No, I won't play it! I won't!" Kai is shouting so loudly everyone in the block can hear. One wouldn't expect a ten-year-old child to be capable of producing such a noise.

"Come back here!" As Chunyu jumps down the two concrete steps below the entrance, Kai grabs on to a small willow tree that's just been planted, swings around in a half circle, then shoots off like a bullet down a small alleyway.

Chunyu hesitates for a while. Above her, she can hear her neighbor Old Jia saying to Old Zun, who lives on the third floor, "If Kai doesn't get into music school this time, he's had it. Next year he'll be too old."

"He's always playing the same pieces," Old Zun replies. "I know them by heart." Then he shouts down to Chunyu, "Your piano's sounding terrible these days! You should pay someone to come and tune it."

Chunyu ignores the men's remarks. She and her husband spent every last yuan they owned to buy that piano. Chunyu hasn't always been so poor--she was born into a wealthy family. When the Communists liberated China in 1949, she cut herself off from her parents and took active steps to join the party. As a result, she was able to secure a place at Beijing's Central Academy of Music. Unfortunately, just before she was due to graduate, an officer discovered an old photograph she'd been hiding that showed her playing the piano to a group of her parents' bourgeois friends. She was consequently labeled a rightist, and as Old Liu, who was her boyfriend at the time, refused to denounce her, they were both sent to a labor camp in the remote northwest where they remained for twenty-four years.

Chunyu scrapes back her hair and runs down the alleyway in pursuit of her son, shouting, "Come back, you little beast!"

In the light of the setting sun, she sees Kai swooping down the alley like a cockerel in flight. She steps up her speed. Since she isn't wearing socks, her feet grip well to her rubber-soled shoes. She feels as though she has the wind under her feet.

When she was eighteen, after a year of running more than ten kilometers a day from her Beijing lodgings to the Academy of Music and back, she became champion of the academy's annual long-distance race. Although she's now fifty-three years old, her legs are still strong. Last month she managed to chase after and catch a thief who'd stolen a tape recorder while wandering around her block pretending to deliver leaflets on a new brand of lipstick.

"Come back. If you don't stop, I'll kill you!"

Her son is wearing his school uniform: a white cotton suit with blue piping along the seams. His red necktie is as bright as a cockscomb. He pumps his arms as he runs. Chunyu is convinced that as long as she maintains her speed, she'll be able to catch him in less than twenty seconds. But she soon realizes that she can't match his pace, just as a duck can never match the pace of a chicken. She suspects that she's put on weight again. She's been concerned about her weight for the last ten years, ever since she and Old Liu were rehabilitated in 1981, and released from the labor camp. As soon as had she returned home, and arranged for a family portrait to be taken in a photographer's studio to celebrate the event, than her body started to balloon. As an adolescent, Chunyu was one of the prettiest girls in the town. Whenever she walked down the street, men would stop and gawk. But when she returned from the camp, her face looked so old that no one recognized her.

The little rascal who's running in front of her now was just three months old when the family portrait was taken. Chunyu was just forty-three, and still had a lot of life left to devote to the party and to herself. Within a few months, Old Liu's party membership was reinstated and he was assigned a post in the political office of a coal processing plant. Chunyu was appointed cultural officer of the Municipal Music Association, a post she held for nine years, until last year when she was promoted to chairwoman of the local neighborhood committee.

Back in 1981, her daughter, Xin, who was twelve years old, was preparing to take the entrance exam to the local music school. Chunyu had the key to the Music Association's piano room. During the day, she used the piano for teaching purposes, and let Xin practice on it in the evening. Chunyu bought all the sheet music that her daughter needed, and charged it to the Music Association. The family was now well provided for, and had a goal to work toward. Everything seemed to be going well. In 1983, Chunyu and Old Liu received eight thousand yuan in compensation for the years they spent in the labor camp. After Liu paid the 260-yuan party membership fee, they had just enough left over to order a small upright piano, which was delivered to them a year later. As life became easier following the implementation of the Open Door Policy, Chunyu's spirits improved, and so did her appetite. But, unlike Old Liu, she liked to keep active. Every day, she'd get up at dawn and hold dance classes outside the Open Door Club. She wanted to retrieve all the lost years of her youth, and was determined to keep her weight down to under seventy-five kilos. But she needn't have worried, because since Xin became ill six years ago, and then died two years later, Chunyu hasn't put on a gram of weight.

Her legs are now aching from the sudden sprint she made a few minutes ago. She's worried that her left kneecap has become dislodged. She watches her son swerve to the right and scurry down Construction Alley. That's where his school is.

"I bet he's going to jump over the school wall," she thinks to herself. "The little terror. He knows that I'm afraid of heights. I get vertigo just walking downstairs." When Chunyu was six years old, she once jumped off the balcony of her parents' apartment to avoid having to play the piano to her mother's friends. By then she could already play Beethoven's "Fur Elise" and Mendelssohn's "Spring Song" by heart. She injured herself so badly in the fall that she had to stay at home for three months. When she returned to school she was unable to catch up with the other children, so her parents decided to send her to a private music school instead, where she could concentrate on the piano.

"What's the hurry?" cries a friend of Old Liu's as Chunyu dashes past.

"Kai's trying to run away!" Chunyu shouts back, without turning around. It occurs to her that when her son was younger she didn't pay enough attention to him. She focused all of her energy on Xin. She was convinced that as long as Xin followed the practice plan that she'd devised, she would easily get a place at Beijing's Central Academy of Music. Xin looked just like Chunyu did as a young girl, but was even more talented. In the labor camp, when Xin saw a piano for the first time, in the film of the model play The Red Lantern, she immediately announced that she wanted to be a pianist when she grew up. Chunyu drew the notes of a keyboard along the edge of their brick bed, and within a few days, Xin was able to tap out the notes for the song "Nothing is redder than the sun, and no one is dearer to us than Chairman Mao Zedong." Xin's musical talent gave Chunyu a sense of purpose. She was determined that her daughter would become a great pianist, and succeed where she herself had failed.

But Chunyu could never have guessed that just four years after the family was released from the labor camp, her daughter would develop bone cancer. Xin was admitted to the hospital, and for the first two years, Chunyu's work unit paid for all the medical costs. But when Xin reached the age of eighteen, the payments came to an end. Without medical treatment, Xin's condition deteriorated drastically. The chief surgeon, Dr. Han, told Chunyu that Xin needed an emergency operation, and before this could take place, the hospital would require a payment of 40,000 yuan.

This sum was the equivalent of five years of Chunyu's and Old Liu's combined incomes. After a long discussion, the couple decided that Old Liu should take early retirement. From this he would gain a onetime pension award of 20,000 yuan. They calculated that they could then get 9,000 yuan from selling their piano and fridge, and borrow another 2,000 from close friends, which would give them a total of 31,000 yuan--just 9,000 yuan short of the sum the hospital demanded.

Through a backdoor connection, the couple asked an acquaintance to give the hospital director two bottles of French wine and two gift-wrapped jars of Nescafe and Coffee-mate. After accepting this bribe, the director agreed that Xin's operation could go ahead immediately, and gave the couple two weeks to pay the remaining 9,000 yuan. Xin underwent surgery the next day. After the operation, Dr. Han informed the couple that although the tumor had been successfully excised from Xin's pelvic bone, the cancer had spread to her stomach, and that she would now need a course of chemotherapy. For this additional treatment, the hospital required a further 10,000 yuan.

In an effort to start raising the money, Old Liu bought a wooden handcart and wheeled it around town looking for work. Many buildings were being demolished at the time, so there was plenty of work to be found. Old Liu could make forty or fifty yuan a day carting rubble from building sites to rubbish tips. Two weeks later, Old Liu handed the hospital the few hundred yuan that he'd made, and promised to pay the rest of the money as soon as he could. The director of the hospital told him that this money would cover only one more dose of anti-inflammatory drugs, and that once this was administered, his daughter would have to leave the hospital. Chunyu was devastated.

Cuprins

Introduction

ANDRE DUBUS I I I

Where Are You Running To?

MA JIAN

China

Introduced by Jonathan Safran Foer

Translated from the Chinese by Flora Drew

Meteorite Mountain

CAN XUE

China

Introduced by Ha Jin

Translated from the Chinese by Zhu Hong

Looking for the Elephant

JO KYUNG RAN

South Korea

Introduced by Don Lee

Translated from the Korean by Heinz Insu Fenkl

Children of the Sky

SENO GUMIRA AJIDARMA

Indonesia

Introduced by Pramoedya Ananta Toer

Translated from the Indonesian by John H.McGlynn

The Scripture Read Backward

PARASHURAM

Bangladesh

Introduced by Amit Chaudhuri

Translated from the Bengali by Sukanta Chaudhuri

The Unfinished Game

GOLI TARAGHI

Iran

Introduced by Francine Prose

Translated from the Persian by Zara Houshmand

The Day in Buenos Aires

JABBAR YUSSIN HUSSIN

Iraq

Introduced by Alberto Manguel

Translated from the Arabic by Randa Jarrar

Two Poems

SANIYYA SALEH

Syria

Introduced by Adonis

Translated from the Arabic by Issa J. Boullata

Faint Hints of Tranquillity

ADANIA SHIBLI

Palestine

Introduced by Anton Shammas

Translated from the Arabic by Anton Shammas

Shards of Reality and Glass

HASSAN KHADER

Palestine

Introduced by Ahdaf Soueif

Translated from the Arabic by Ahdaf Soueif

A Drowsy Haze

GAMAL AL-GHITANI

Egypt

Introduced by Naguib Mahfouz

Translated from the Arabic by William Maynard Hutchins

The Uses of English

AKINWUMI ISOLA

Nigeria

Introduced by Wole Soyinka

Translated from the Yoruba by Akinwumi Isola

from Provisional

GABRIELA ADAMESTEANU

Romania

Introduced by Norman Manea

Translated from the Romanian by Carrie Messenger

Two Poems

SENADIN MUSABEGOVIC´

Bosnia

Introduced by Aleksandar Hemon

Translated from the Bosnian by Ulvija Tanovi´c

from Experiment with India

GIORGIO MANGANELLI

Italy

Introduced by Roberto Calasso

Translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein

from The Fish of Berlin

ELEONORA HUMMEL

Germany

Introduced by Günter Grass

Translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky

Seven Poems

BRONISLAW MAJ

Poland

Introduced by the Editors

Translated by Clare Cavanagh

from His Majesty, Almighty Death

MYRIAM ANISSIMOV

France

Introduced by Cynthia Ozick

Translated from the French by C. Dickson

from October 27, 2003

ETEL ADNAN

France

Introduced by Diana Abu Jaber

Translated from the French by C. Dickson with Etel Adnan

Vietnam.Thursday.

JOHAN HARSTAD

Norway

Introduced by Heidi Julavits

Translated from the Norwegian by Deborah Dawkin and Erik Skuggevik

Lightweight Champ

JUAN VILLORO

Mexico

Introduced by Javier Marías

Translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

The Sheika’s Condition

MARIO BELLATIN

Mexico

Introduced by Francisco Goldman

Translated from the Spanish by Cindy Schuster

When I Was a Man

AMBAR PAST

Mexico

Introduced by Elena Poniatowska

Translated from the Spanish by Samantha Schnee

from Revulsion

HORACIO CASTELLANOS MOYA

El Salvador

Introduced by Roberto Bolaño

Translated from the Spanish by Beatriz Cortez

The Chareron Inheritance

EVELYNE TROUILLOT

Haiti

Introduced by Edwidge Danticat

Translated from the French by Avriel Goldberger

from Kind’s Silence

MARCELA SOLÁ

Argentina

Introduced by Luisa Valenzuela

Translated from the Spanish by Tobias Hecht

Baked Mud

JUAN JOSÉ SAER

Argentina

Introduced by José Saramago

Translated from the Spanish by Sergio Waisman

Swimming at Night

JUAN FORN

Argentina

Introduced by Ariel Dorfman

Translated from the Spanish by Marina Harss

ANDRE DUBUS I I I

Where Are You Running To?

MA JIAN

China

Introduced by Jonathan Safran Foer

Translated from the Chinese by Flora Drew

Meteorite Mountain

CAN XUE

China

Introduced by Ha Jin

Translated from the Chinese by Zhu Hong

Looking for the Elephant

JO KYUNG RAN

South Korea

Introduced by Don Lee

Translated from the Korean by Heinz Insu Fenkl

Children of the Sky

SENO GUMIRA AJIDARMA

Indonesia

Introduced by Pramoedya Ananta Toer

Translated from the Indonesian by John H.McGlynn

The Scripture Read Backward

PARASHURAM

Bangladesh

Introduced by Amit Chaudhuri

Translated from the Bengali by Sukanta Chaudhuri

The Unfinished Game

GOLI TARAGHI

Iran

Introduced by Francine Prose

Translated from the Persian by Zara Houshmand

The Day in Buenos Aires

JABBAR YUSSIN HUSSIN

Iraq

Introduced by Alberto Manguel

Translated from the Arabic by Randa Jarrar

Two Poems

SANIYYA SALEH

Syria

Introduced by Adonis

Translated from the Arabic by Issa J. Boullata

Faint Hints of Tranquillity

ADANIA SHIBLI

Palestine

Introduced by Anton Shammas

Translated from the Arabic by Anton Shammas

Shards of Reality and Glass

HASSAN KHADER

Palestine

Introduced by Ahdaf Soueif

Translated from the Arabic by Ahdaf Soueif

A Drowsy Haze

GAMAL AL-GHITANI

Egypt

Introduced by Naguib Mahfouz

Translated from the Arabic by William Maynard Hutchins

The Uses of English

AKINWUMI ISOLA

Nigeria

Introduced by Wole Soyinka

Translated from the Yoruba by Akinwumi Isola

from Provisional

GABRIELA ADAMESTEANU

Romania

Introduced by Norman Manea

Translated from the Romanian by Carrie Messenger

Two Poems

SENADIN MUSABEGOVIC´

Bosnia

Introduced by Aleksandar Hemon

Translated from the Bosnian by Ulvija Tanovi´c

from Experiment with India

GIORGIO MANGANELLI

Italy

Introduced by Roberto Calasso

Translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein

from The Fish of Berlin

ELEONORA HUMMEL

Germany

Introduced by Günter Grass

Translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky

Seven Poems

BRONISLAW MAJ

Poland

Introduced by the Editors

Translated by Clare Cavanagh

from His Majesty, Almighty Death

MYRIAM ANISSIMOV

France

Introduced by Cynthia Ozick

Translated from the French by C. Dickson

from October 27, 2003

ETEL ADNAN

France

Introduced by Diana Abu Jaber

Translated from the French by C. Dickson with Etel Adnan

Vietnam.Thursday.

JOHAN HARSTAD

Norway

Introduced by Heidi Julavits

Translated from the Norwegian by Deborah Dawkin and Erik Skuggevik

Lightweight Champ

JUAN VILLORO

Mexico

Introduced by Javier Marías

Translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

The Sheika’s Condition

MARIO BELLATIN

Mexico

Introduced by Francisco Goldman

Translated from the Spanish by Cindy Schuster

When I Was a Man

AMBAR PAST

Mexico

Introduced by Elena Poniatowska

Translated from the Spanish by Samantha Schnee

from Revulsion

HORACIO CASTELLANOS MOYA

El Salvador

Introduced by Roberto Bolaño

Translated from the Spanish by Beatriz Cortez

The Chareron Inheritance

EVELYNE TROUILLOT

Haiti

Introduced by Edwidge Danticat

Translated from the French by Avriel Goldberger

from Kind’s Silence

MARCELA SOLÁ

Argentina

Introduced by Luisa Valenzuela

Translated from the Spanish by Tobias Hecht

Baked Mud

JUAN JOSÉ SAER

Argentina

Introduced by José Saramago

Translated from the Spanish by Sergio Waisman

Swimming at Night

JUAN FORN

Argentina

Introduced by Ariel Dorfman

Translated from the Spanish by Marina Harss

Descriere

From the editors of "Words Without Borders," a trailblazing online magazine for international literature, comes this cutting-edge anthology of more than 20 literary discoveries from around the globe, each published in English for the first time.