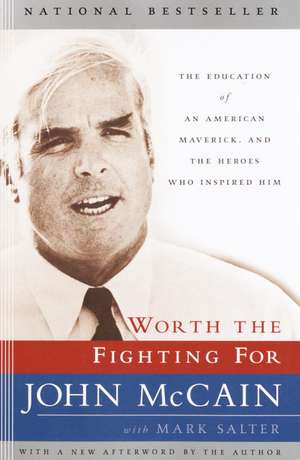

Worth the Fighting for: The Education of an American Maverick, and the Heroes Who Inspired Him

Autor John McCain Mark Salteren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2003

Worth the Fighting For

After five and a half years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam, naval aviator John McCain returned home a changed man. Regaining his health and flight-eligibility status, he resumed his military career, commanding carrier pilots and serving as the navy’s liaison to what is sometimes ironically called the world’s most exclusive club, the United States Senate. Accompanying Senators John Tower and Henry “Scoop” Jackson on international trips, McCain began his political education in the company of two masters, leaders whose standards he would strive to maintain upon his election to the U.S. Congress. There, he learned valuable lessons in cooperation from a good-humored congressman from the other party, Morris Udall. In 1986, McCain was elected to the U.S. Senate, inheriting the seat of another role model, Barry Goldwater.

During his time in public office, McCain has seen acts of principle and acts of craven self-interest. He describes both ex-tremes in these pages, with his characteristic straight talk and humor. He writes honestly of the lowest point in his career, the Keating Five savings and loan debacle, as well as his triumphant moments—his return to Vietnam and his efforts to normalize relations between the U.S. and Vietnamese governments; his fight for campaign finance reform; and his galvanizing bid for the presidency in 2000.

Writes McCain: “A rebel without a cause is just a punk. Whatever you’re called—rebel, unorthodox, nonconformist, radical—it’s all self-indulgence without a good cause to give your life meaning.” This is the story of McCain’s causes, the people who made him do it, and the meaning he found. Worth the Fighting For reminds us of what’s best in America, and in ourselves.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 75.69 lei

Preț vechi: 89.54 lei

-15% Nou

Puncte Express: 114

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.49€ • 14.96$ • 12.06£

14.49€ • 14.96$ • 12.06£

Disponibilitate incertă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812969740

ISBN-10: 081296974X

Pagini: 404

Ilustrații: 19 SECTION-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Rh Trade Pbk.

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 081296974X

Pagini: 404

Ilustrații: 19 SECTION-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Rh Trade Pbk.

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

John McCain is a United States senator from Arizona. He retired from the navy as a captain in 1981, and was first elected to Congress in 1982. He is currently serving his third term in the Senate. He and his wife, Cindy, live with their children in Phoenix, Arizona. With Mark Salter, he is at work on his third book, about courage, which Random House will publish in the fall of 2003.

Mark Salter has worked on Senator McCain’s staff for thirteen years and is the co-author of Faith of My Fathers. Hired as a legislative assistant in 1989, he has served as the senator’s administrative assistant since 1993. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with his wife, Diane, and their two daughters.

From the Hardcover edition.

Mark Salter has worked on Senator McCain’s staff for thirteen years and is the co-author of Faith of My Fathers. Hired as a legislative assistant in 1989, he has served as the senator’s administrative assistant since 1993. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with his wife, Diane, and their two daughters.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

From Chapter 1

Last Salute

We buried my father on a morning in the early spring of 1981. He had died of heart failure five days before, over the Atlantic, with my mother, his wife of forty-eight years, by his side.

He had been in poor health for most of the nine years that had passed since he had reluctantly retired from the navy. In his last few years, you could see life draining out of him. He had lost weight and become quite frail. He walked slowly, with his shoulders stooped, and was easily tired. He spent most of every day in his study, where he would read and nap on and off for hours. In his last year of active duty, as commander in chief of U.S. forces in the Pacific, he had suffered a seizure, which was initially believed to be a small stroke. For the remainder of his life, the seizures would recur more and more frequently, each one worse than the last, enfeebling him and destroying the great spirit that had enabled such a small man to live courageously a big, accomplished, adventurous life.

His doctors could never determine the cause of his convulsions. In his last years, they were as dramatic as grand mal seizures suffered by epileptics. He would bite through objects placed in his mouth to prevent him from swallowing his tongue. It seemed his brain would just quit functioning for longer and longer intervals. We would take him to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, where he would convalesce for a few weeks, while doctors searched futilely for a diagnosis.

I have always suspected that my father's long years of binge drinking had ruined his health. He had given up drinking years before, joined Alcoholics Anonymous, and although he would occasionally fall off the wagon, for the most part he maintained an admirable discipline in his sober years. But I suspect the damage had been done long ago, and with the onset of old age, the effects of his vice had shortened his life.

More damaging than drink, however, was the sadness he struggled to keep at bay since the day President Richard Nixon had presided over his change of command as a navy CINC, effectively ending more than forty years of active duty in the United States Navy. I've never known anyone who loved his profession more than my father had loved the navy. It was his whole life, from birth to death. He loved my mother, my sister, and my brother. But had you asked him to describe his family relationships, he would have answered, "I'm the son of an admiral and the father of a captain." He was so proud to be a sailor, considered himself so blessed to have remained always in the company of sailors, to have fought at sea, to have risen to the rank his father held, that any other life seemed dismal and insignificant to him.

Annually, all the CINCs are required to testify before the Armed Services Committees of the House and Senate. In his last testimony, aware that his career was near an end, he had complained that he didn't want to retire. But having reached the pinnacle of his career, having held the highest operational command in the navy, he knew his age and declining health had left him bereft of any hope that he would die in the uniform of his country. I am certain he would have preferred to leave this earth, as his father had, triumphantly, as his last war and command ended.

Even if his health had been better, even if his retirement had been occupied with important work and adventures, I doubt it would have alleviated his despair over leaving the navy. He kept the company of old sailors, which he cherished, but their society couldn't compensate him for the work he had lost, for his sense of purpose, for the ships that sailed at another's command, for the bluejackets who loved him, for the sea. He wasn't an invalid, but the seizures were debilitating, his spirits were poor, the quality of his life degraded. On good days, he would go downtown to the Army-Navy Club and swap stories with his old cronies. Most days, however, he remained in his study.

He did manage to travel fairly often. My parents loved to travel, especially my mother, and there were few countries they had not visited in the course of his long career. They tried to maintain their peripatetic lives to the extent my father's health would permit it. And it was on a return flight from Europe that he suffered the seizure that stopped his heart.

I received a call from my former wife, Carol, on a Sunday evening, March 22, 1981. Navy officials had contacted her after they had failed to locate me. They left it to her to inform me that my father had died, which she did with great kindness and tact. A crew member of the air force C-5 cargo plane had radioed a message that my father had suffered a heart attack on board and was presumed dead. The plane had landed at Bangor, Maine, to refuel, where a doctor confirmed my father's death and from there left for Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, D.C., where I would meet it. It was about a twenty-minute drive from my home to Andrews. I remember nothing of it. I cannot recall what I was thinking, or anything I said to my wife, Cindy, during the drive, or what she said to me.

The C-5 is a massive airplane, the largest plane ever built. It had three levels. On the top level, behind the cockpit and the seats for the rest of the crew, was a small passenger compartment with about twelve seats. You had to climb two ladders to reach it, and as I did so, I wondered how my father had managed the climb. My mother greeted us as we entered the compartment. She was very composed, very matter-of-fact, as she informed me, "John, your father is dead." My mother had dedicated her entire life to my father and his career. She loved him greatly. But she is a strong woman, indomitable. No loss, no matter how grievous, could undo her. Her face blank, she stared into my eyes for a long moment, as much, I suppose, to convey her own formidable resolve to maintain her dignity as to see if I could maintain mine. I looked past her toward a space behind the passenger seats, where he was lying, covered with a blue blanket, his brown shoes still on his feet, sticking out from under the blanket.

I remember little of the five days between that moment and the morning we buried him at Arlington National Cemetery, among the rows of white headstones that mark the many thousands of carefully tended graves on its sloping green acres, not far from where his father lay. My brother, Joe, had worked with the navy to make most of the funeral and burial arrangements. I was preparing to move across the country, and my mother was occupied with hundreds of sympathy calls and visits.

The funeral service was held in the Ft. Myers Chapel next to the cemetery. Mourners filled all its pews and stood along its walls and in the back. Nancy Reagan, just a few days after her husband, the president, had narrowly survived an assassination attempt, attended, as did Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger.

The navy, past and present, was represented by many of its most senior and honored officers, along with many eminent officers from the other services. The chief of naval operations, Admiral Tom Hayward, was there, as were his predecessors, Admirals Tom Moorer and George Anderson. Also among the mourners was Admiral Ike Kidd, a dear friend of my parents and the son of the famous Admiral Kidd (who had been killed at Pearl Harbor and received the Medal of Honor posthumously). He was overcome with grief, and one of my most poignant memories of the funeral is of Admiral Kidd sobbing loudly and struggling to regain his composure. The pallbearers included Admiral Arleigh Burke, whom my father had served under and revered; Admiral "Red" Ramage, a classmate, fellow submariner, and Medal of Honor recipient; General Eugene Tighe of the U.S. Air Force; Ellsworth Bunker, who had served as ambassador to South Vietnam when my father held the Pacific Command; Chief Roque Acuavera and Chief Ricardo San Victories, each of whom had served my father as chief steward for many years and who had loved him and been loved by him.

Joe and I were the only eulogists. Joe spoke first and gave a fine tribute, eloquently sketching his career and character. I spoke briefly and remember only joking that my father had probably greeted St. Peter with his lecture on "The Four Ocean Navy and the Soviet Threat." I closed my remarks with the Robert Louis Stevenson poem "Requiem," the beautiful homage to one man's free will that we had both loved.

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

After the funeral service had ended, the mourners preceded my father's body to his burial site. It was a cool, overcast day; the trees were still bare and seemed so black against the gray sky and deep green field. We watched as a riderless horse slowly led the caisson and procession from chapel to grave. As they arrived, the Navy Band played a solemn march by Handel, the music that had accompanied Lord Nelson's funeral procession as it moved through the streets of London to his resting place at St. Paul's Cathedral. I kept my head erect and my eyes fixed straight ahead during the brief graveside service and as his casket was lowered into the earth.

After the service, my mother hosted a reception in her large Connecticut Avenue apartment. I was not distraught at the service or at the reception, but I was weary and had to force myself to be affable. At times I found it trying just to thank people for coming and for their expressions of sympathy. But my mother, my amazing mother, more than compensated for my reserve as she whirled around the apartment, seeming to take part in every conversation, as always, the center of attention.

My father's death and funeral occurred at a moment of great change for me and for the tradition that had brought honor to three generations of John McCains. I had arrived at my mother's apartment still wearing my dress blue uniform. I would never wear it again.

I left the reception after an hour or so and drove to an office in a nondescript building in Crystal City, Virginia, with the typically bureaucratic title Navy Personnel Support Activity Center. There I signed my discharge papers, applied for my retirement pay and health coverage, and turned in my identification card, ending nearly twenty-three years on active duty. For the first time in the twentieth century, and possibly forever, the name John McCain was missing from navy rosters. From there, I drove to the airport and boarded a plane with Cindy and her parents for Phoenix, Arizona, and a new life altogether.

From the Hardcover edition.

Last Salute

We buried my father on a morning in the early spring of 1981. He had died of heart failure five days before, over the Atlantic, with my mother, his wife of forty-eight years, by his side.

He had been in poor health for most of the nine years that had passed since he had reluctantly retired from the navy. In his last few years, you could see life draining out of him. He had lost weight and become quite frail. He walked slowly, with his shoulders stooped, and was easily tired. He spent most of every day in his study, where he would read and nap on and off for hours. In his last year of active duty, as commander in chief of U.S. forces in the Pacific, he had suffered a seizure, which was initially believed to be a small stroke. For the remainder of his life, the seizures would recur more and more frequently, each one worse than the last, enfeebling him and destroying the great spirit that had enabled such a small man to live courageously a big, accomplished, adventurous life.

His doctors could never determine the cause of his convulsions. In his last years, they were as dramatic as grand mal seizures suffered by epileptics. He would bite through objects placed in his mouth to prevent him from swallowing his tongue. It seemed his brain would just quit functioning for longer and longer intervals. We would take him to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, where he would convalesce for a few weeks, while doctors searched futilely for a diagnosis.

I have always suspected that my father's long years of binge drinking had ruined his health. He had given up drinking years before, joined Alcoholics Anonymous, and although he would occasionally fall off the wagon, for the most part he maintained an admirable discipline in his sober years. But I suspect the damage had been done long ago, and with the onset of old age, the effects of his vice had shortened his life.

More damaging than drink, however, was the sadness he struggled to keep at bay since the day President Richard Nixon had presided over his change of command as a navy CINC, effectively ending more than forty years of active duty in the United States Navy. I've never known anyone who loved his profession more than my father had loved the navy. It was his whole life, from birth to death. He loved my mother, my sister, and my brother. But had you asked him to describe his family relationships, he would have answered, "I'm the son of an admiral and the father of a captain." He was so proud to be a sailor, considered himself so blessed to have remained always in the company of sailors, to have fought at sea, to have risen to the rank his father held, that any other life seemed dismal and insignificant to him.

Annually, all the CINCs are required to testify before the Armed Services Committees of the House and Senate. In his last testimony, aware that his career was near an end, he had complained that he didn't want to retire. But having reached the pinnacle of his career, having held the highest operational command in the navy, he knew his age and declining health had left him bereft of any hope that he would die in the uniform of his country. I am certain he would have preferred to leave this earth, as his father had, triumphantly, as his last war and command ended.

Even if his health had been better, even if his retirement had been occupied with important work and adventures, I doubt it would have alleviated his despair over leaving the navy. He kept the company of old sailors, which he cherished, but their society couldn't compensate him for the work he had lost, for his sense of purpose, for the ships that sailed at another's command, for the bluejackets who loved him, for the sea. He wasn't an invalid, but the seizures were debilitating, his spirits were poor, the quality of his life degraded. On good days, he would go downtown to the Army-Navy Club and swap stories with his old cronies. Most days, however, he remained in his study.

He did manage to travel fairly often. My parents loved to travel, especially my mother, and there were few countries they had not visited in the course of his long career. They tried to maintain their peripatetic lives to the extent my father's health would permit it. And it was on a return flight from Europe that he suffered the seizure that stopped his heart.

I received a call from my former wife, Carol, on a Sunday evening, March 22, 1981. Navy officials had contacted her after they had failed to locate me. They left it to her to inform me that my father had died, which she did with great kindness and tact. A crew member of the air force C-5 cargo plane had radioed a message that my father had suffered a heart attack on board and was presumed dead. The plane had landed at Bangor, Maine, to refuel, where a doctor confirmed my father's death and from there left for Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, D.C., where I would meet it. It was about a twenty-minute drive from my home to Andrews. I remember nothing of it. I cannot recall what I was thinking, or anything I said to my wife, Cindy, during the drive, or what she said to me.

The C-5 is a massive airplane, the largest plane ever built. It had three levels. On the top level, behind the cockpit and the seats for the rest of the crew, was a small passenger compartment with about twelve seats. You had to climb two ladders to reach it, and as I did so, I wondered how my father had managed the climb. My mother greeted us as we entered the compartment. She was very composed, very matter-of-fact, as she informed me, "John, your father is dead." My mother had dedicated her entire life to my father and his career. She loved him greatly. But she is a strong woman, indomitable. No loss, no matter how grievous, could undo her. Her face blank, she stared into my eyes for a long moment, as much, I suppose, to convey her own formidable resolve to maintain her dignity as to see if I could maintain mine. I looked past her toward a space behind the passenger seats, where he was lying, covered with a blue blanket, his brown shoes still on his feet, sticking out from under the blanket.

I remember little of the five days between that moment and the morning we buried him at Arlington National Cemetery, among the rows of white headstones that mark the many thousands of carefully tended graves on its sloping green acres, not far from where his father lay. My brother, Joe, had worked with the navy to make most of the funeral and burial arrangements. I was preparing to move across the country, and my mother was occupied with hundreds of sympathy calls and visits.

The funeral service was held in the Ft. Myers Chapel next to the cemetery. Mourners filled all its pews and stood along its walls and in the back. Nancy Reagan, just a few days after her husband, the president, had narrowly survived an assassination attempt, attended, as did Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger.

The navy, past and present, was represented by many of its most senior and honored officers, along with many eminent officers from the other services. The chief of naval operations, Admiral Tom Hayward, was there, as were his predecessors, Admirals Tom Moorer and George Anderson. Also among the mourners was Admiral Ike Kidd, a dear friend of my parents and the son of the famous Admiral Kidd (who had been killed at Pearl Harbor and received the Medal of Honor posthumously). He was overcome with grief, and one of my most poignant memories of the funeral is of Admiral Kidd sobbing loudly and struggling to regain his composure. The pallbearers included Admiral Arleigh Burke, whom my father had served under and revered; Admiral "Red" Ramage, a classmate, fellow submariner, and Medal of Honor recipient; General Eugene Tighe of the U.S. Air Force; Ellsworth Bunker, who had served as ambassador to South Vietnam when my father held the Pacific Command; Chief Roque Acuavera and Chief Ricardo San Victories, each of whom had served my father as chief steward for many years and who had loved him and been loved by him.

Joe and I were the only eulogists. Joe spoke first and gave a fine tribute, eloquently sketching his career and character. I spoke briefly and remember only joking that my father had probably greeted St. Peter with his lecture on "The Four Ocean Navy and the Soviet Threat." I closed my remarks with the Robert Louis Stevenson poem "Requiem," the beautiful homage to one man's free will that we had both loved.

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

After the funeral service had ended, the mourners preceded my father's body to his burial site. It was a cool, overcast day; the trees were still bare and seemed so black against the gray sky and deep green field. We watched as a riderless horse slowly led the caisson and procession from chapel to grave. As they arrived, the Navy Band played a solemn march by Handel, the music that had accompanied Lord Nelson's funeral procession as it moved through the streets of London to his resting place at St. Paul's Cathedral. I kept my head erect and my eyes fixed straight ahead during the brief graveside service and as his casket was lowered into the earth.

After the service, my mother hosted a reception in her large Connecticut Avenue apartment. I was not distraught at the service or at the reception, but I was weary and had to force myself to be affable. At times I found it trying just to thank people for coming and for their expressions of sympathy. But my mother, my amazing mother, more than compensated for my reserve as she whirled around the apartment, seeming to take part in every conversation, as always, the center of attention.

My father's death and funeral occurred at a moment of great change for me and for the tradition that had brought honor to three generations of John McCains. I had arrived at my mother's apartment still wearing my dress blue uniform. I would never wear it again.

I left the reception after an hour or so and drove to an office in a nondescript building in Crystal City, Virginia, with the typically bureaucratic title Navy Personnel Support Activity Center. There I signed my discharge papers, applied for my retirement pay and health coverage, and turned in my identification card, ending nearly twenty-three years on active duty. For the first time in the twentieth century, and possibly forever, the name John McCain was missing from navy rosters. From there, I drove to the airport and boarded a plane with Cindy and her parents for Phoenix, Arizona, and a new life altogether.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Praise for Faith of My Fathers

“Poignant, harrowing, and sometimes hilarious.”

—The Washington Post

“Hard to top and impossible to read without being moved.”

—USA Today

“Compelling, even inspiring.” —Time

“Not only moving but wise.” —Los Angeles Times

From the Hardcover edition.

“Poignant, harrowing, and sometimes hilarious.”

—The Washington Post

“Hard to top and impossible to read without being moved.”

—USA Today

“Compelling, even inspiring.” —Time

“Not only moving but wise.” —Los Angeles Times

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The "New York Times" bestseller follows the education of an American maverickand the heroes who inspired him, by "one of the most inspiring public figuresof our time" ("Washington Post Book World").