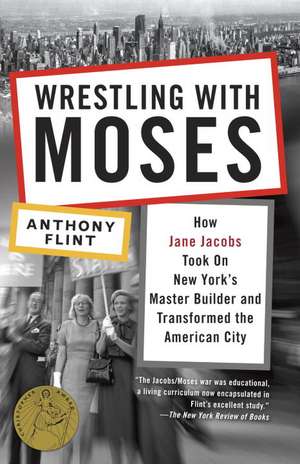

Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took on New York's Master Builder and Transformed the American City

Autor Anthony Flinten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2011

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Christopher Awards (2010)

Preț: 154.75 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 232

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.62€ • 30.80$ • 24.45£

29.62€ • 30.80$ • 24.45£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812981360

ISBN-10: 0812981367

Pagini: 231

Ilustrații: 16-PP B/W PHOTO SECTION + CHAPTER-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812981367

Pagini: 231

Ilustrații: 16-PP B/W PHOTO SECTION + CHAPTER-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Anthony Flint is the director of public affairs at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a think-tank on land and development issues located in Cambridge, MA, and was a reporter at The Boston Globe for sixteen years. He is the author of This Land: The Battle Over Sprawl and the Future of America. He lives in Boston.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

The Girl from Scranton

As the rattling subway train slowed to a stop, Jane Butzner looked up to see the name of the station, its colorful lettering standing out against the white-tile station walls as it flashed by again and again, finally readable: Christopher Street/Sheridan Square. As the doors opened, she watched as a crowd poured out, moving past pretty mosaics to the exit.

She had moved to New York from her hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, and had joined her sister, Betty, in a small apartment in Brooklyn a few months before. She was hunting for a job, but the morning's interview had concluded swiftly, so she'd decided to explore her new city. She darted out before the doors slid shut and made her way through the turnstile and up a set of stairs to the street. Without knowing it, Jane had alighted in the heart of Greenwich Village, the place she would call home for decades to come.

As she emerged, she immediately noticed that the streets ran off at odd angles in all directions. She saw storefronts with awnings shading cluttered sidewalks, kids chasing one another in front of a grocery, delivery trucks stopping and starting their way up the street. Walking north on Seventh Avenue, she saw the skyscrapers of midtown in the distance and, when she turned around, the cluster of tall buildings in the financial district to the south. But in this spot most buildings were two or three stories, and few were higher than five or six. They were simple: no grand entrances, no soaring edifices. She gazed at shopwindows full of leather handbags and watches and jewelry, strolled past barbershops and cafés, and ran her fingers over the daily newspapers stacked high in front of shelves inside filled with candy and cigars. Everywhere she looked she saw people-people talking to one another, it seemed, every few feet, among them longshoremen headed to taverns at the end of their shifts, casually dressed women window-shopping, old men with hands clasped on canes sitting on the benches in a triangular park. Mothers sat on stoops watching over it all. Everyone looked, she thought, the way she felt: unpretentious, genuine, living their lives. This was home.

Arriving at her Brooklyn apartment that evening, Jane described the wonders of the neighborhood she had seen, concluding simply, "Betty, I found out where we have to live."

"Where is it?" Betty asked.

"I don't know, but you get in the subway and you get out at a place called Christopher Street."

Jane had moved to New York City in 1934. Armed with a high-school diploma, a recently acquired knowledge of shorthand, and the wisdom of a few months working in the newsroom of a Scranton newspaper, she hoped to break into journalism. She knew it wasn't going to be easy to succeed in a business dominated by men; her assignments in Scranton had been limited to covering weddings, social events, and the meetings of women's civic organizations with names like the Women of the Moose and the Ladies' Nest of Owls No. 3. It was the thick of the Great Depression, and any job was difficult to come by.

Her older sister, Betty, twenty-four, had warned her. Betty had come to New York a few years before with hopes of finding work as an interior designer, but was now grateful to have a job as a salesgirl in the home furnishings section of the Abraham & Straus department store. The headstrong Jane came to the big city anyway, joining her sister in the top floor of a six-floor walk-up in Brooklyn Heights, a neighborhood of Greek and Gothic Revival mansions and Italianate brownstones at the edge of the East River, overlooking Manhattan.

Within weeks of arriving, Jane realized that breaking into journalism was going to take time and that, in the meantime, she'd need to support herself. She began poring over employment agency listings looking for any clerical position she could find, and soon settled into a routine. Each morning she would walk from her apartment building, across the Brooklyn Bridge, and into lower Manhattan, where most of her interviews took place. The rest of her day would be spent exploring the city; she would invest a nickel for a subway ride and get out at random stops. She had been to New York only once before, as a girl of twelve, and now, at eighteen, she was drinking in the sights and sounds of a metropolis that could not be more different from Scranton.

Greenwich Village seemed to capture all the promise of moving to New York City for the young bespectacled girl from eastern Pennsylvania. As soon as she could, Jane brought her sister to Greenwich Village. Betty shared her enthusiasm for the neighborhood, and they quickly found an apartment on Morton Street, just south of the Christopher Street subway station. Morton Street was a classic Greenwich Village lane, running four blocks from east to west from the Hudson River, bending at a forty-five-degree angle in glorious violation of the orderly street grid of the rest of Manhattan. It was lined with petite trees, front-yard gardens, iron fences, and stately rows of four- and five-story brownstones and town houses.

Their neighbors there ranged from truckers and railway workers to artists, painters, and poets, including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and e. e. cummings. The White Horse Tavern, which for decades had been a gathering place for the bohemians of Greenwich Village, stood just around the corner on Hudson Street.

As excited as they were to be there, money was tight. After paying the rent, Jane and Betty had so little to spare that they resorted to mixing Pablum, a nutritious but notably bland cereal for infants, with milk for sustenance.

Their father's advice proved to be wise counsel in this time: that while the girls should pursue the careers of their dreams, they should also learn a practical skill to fall back on. The degree from the Powell secretarial and stenography school in Scranton gave Jane enough of an edge in the barren job market that after months of searching, she finally landed a job as a secretary for a candy manufacturing company. She would serve in similar clerical positions at a clock maker and a drapery hardware business in the years that followed. In her off time, she worked toward her dream career, honing her journalistic skills.

On those afternoons exploring the city after job interviews, and in her off-hours once she started working, she had begun writing down her observations of the city. In time she began to work them into articles. Early on she noticed that every few blocks of the city seemed to have a specialty trade-a little economy all their own. She sought to learn everything she could about these trades, striking up conversations with the shopkeepers and workers pushing racks of furs down the streets, and the leather makers in the deep back rooms into which she peered. Buckets of flowers on the sidewalk would prompt her to probe into the cut-flower trade; wandering through the diamond district on the Bowery on Manhattan's scrappy Lower East Side, she familiarized herself with the intricate system of jewelry auctions.

Immediately upon arriving home from work, she would toss her handbag on the sofa and settle in front of her manual typewriter in her room and write. After a while, she began to submit her pieces to popular magazines of the day. Much to her surprise, she arrived home one evening to find an envelope from an editor at Vogue who wanted to publish a story she had written on the fur district. The editors liked her plainspoken style and keen observations and wished to retain her as a freelance contributor. They proposed that she write four essays over the next two years, for which they would pay her $40 per article, a slightly better rate than the $12 per week she was making as a secretary. Her career as a writer in New York City had officially begun.

Her early journalism reflected an eye for the detail and the drama beneath the quotidian. A 1937 piece on the flower market in lower Manhattan, titled "Flowers Come to Town," began with a typical flourish:

All the ingredients of a lavender-and-old-lace love story, with a rip- roaring, contrasting background, are in New York's wholesale flower district, centered around Twenty-Eighth Street and Sixth Avenue. Under the melodramatic roar of the "El," encircled by hash-houses and Turkish baths, are the shops of hard-boiled, stalwart men, who shyly admit that they are dottles for love, sentiment, and romance.

She went on to describe in detail the 5:00 a.m. arrival of orchids, gardenias, peonies, and lilacs from Connecticut, Long Island, and New Jersey that were then meted out into buckets for sale by retailers. She considered the city's voracious demand for cut flowers and foliage-200 million ferns, 150,000 roses a day from just one grower in a season. It made sense when she thought about it: office reception areas, wedding receptions, society functions, and funerals all needed flowers. It was a big market, but the competition was fierce; she noted how the merchants adopted a set of rules to maintain a level playing field, such as agreeing not to open hampers in the flower market until 6:00 a.m., at the sound of a gong. She was fascinated not only with the mores of the city but with the way systems seemed to self-organize to prosper.

In another article, Jane wrote about the diamond district, which in the 1930s was centered on the Bowery across from the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. She described how the dealers in their beards and hats jotted down notes on the cut stones, rings, necklaces, and lockets that pawnbrokers had sent for display at auction, then made their bids with silent gestures or by squeezing the auctioneer's arm. "Upstairs, in the small light rooms over the stores, diamonds are cut and polished and set or re-set, and silver is buffed. The doors and vestibules to the rooms are barred and there is no superfluous furniture, just the tools and tables where the skillful workmen sit with leather hammocks to catch the chips and dust of diamond and metal," she wrote. "Silver is polished against a cloth-covered revolving wheel . . . All the sweepings are carefully saved to be refined and the silver recovered. The walls and ceilings are brushed and the old oilcloth coverings and work clothes of the men are burned to extract the silver dust. Even the water in which the workmen wash their hands is saved. A small room where silver is polished may yield to a refiner hundreds of dollars worth of metal a year." Outside, meanwhile, is the "lusty tumultuous life of the lower East Side"-the rumble of the elevated subway, "Chinamen from Mott Street," exotic aromas, and bums on the curbstones.

In those first years in New York, Jane worked forty hours a week, typing, filing, and taking dictation. All the while she continued to scout the far reaches of the city, writing for Vogue as well as other periodicals. On one outing she turned her attention to manhole covers, decoding their cryptic inscriptions in order to map the underground rivers of electricity and gas lines, the tributaries of brine to chill the storage areas of produce markets, and the pipes carrying steam to heat skyscrapers. Her account of this subterranean maze, which showed how urban life was made possible by what was underneath, appeared in a New York magazine called Cue, which primarily published theater and restaurant listings. She also wrote feature stories for the Sunday Herald Tribune.

She began to range beyond purely urban subjects, writing about the way fishing boats operated in Chesapeake Bay, the pagan origins of Christmas, and the decorative buttons on military uniform sleeves (originally meant to keep soldiers from using them to wipe their noses). She even tried her hand at short stories, in one piece depicting the decapitation of James Madison in a creative rewriting of American history-"bump, bump, bump" went the founding father's head on the floor, she wrote. An editor at Reader's Digest deemed the piece "too gruesome for us," and apparently other editors reacted in a similar fashion. Jacobs experimented with science fiction, too, writing a story about fast-growing plants with fantastical intentions that similarly went unsold.

But writing about the city remained her passion. She often went up to the rooftop of her apartment building and watched the garbage trucks as they made their way through the city streets, picking the sidewalks clean. She would think, "What a complicated great place this is, and all these pieces of it that make it work." The more she investigated and explored neighborhoods, infrastructure, and business districts for her stories, the more she began to see the city as a living, breathing thing-complex, wondrous, and self-perpetuating.

As she approached her fourth year in New York, Jane began to reconsider her opinion on higher education. It had become clear to her that she needed a boost to get a full-time job as a journalist. From a young age she had rebelled against what she viewed as the insipid curriculum of the Scranton schools, and scorned her teachers, whom she considered dim-witted. She was known to stick her tongue out when teachers' backs were turned and to challenge her teachers routinely. When a fourth-grade teacher claimed that cities formed only around rivers with waterfalls to provide electric power, Jane pointed out that Scranton had a waterfall but it had nothing to do with powering the city or the economy of the place. Another teacher asked her students to promise to brush their teeth every day. But Jane's father had just told her never to make a promise unless she was absolutely certain she could keep it. So she refused and urged her fellow students to do the same. The teacher kicked her out of the classroom, and Jane wandered along empty railroad tracks on her way home for lunch.

Now, in 1938, she used money from her parents to enroll at Columbia University's School of General Studies, more than a hundred blocks north of Greenwich Village, which had open enrollment for "nontraditional" students-those who had interrupted their education or needed to attend part-time. The school's lack of a set curriculum appealed to Jacobs.

At Columbia, she signed up for courses in any subject that interested her-chemistry, geography, geology, law, political science, psychology, and zoology. Before long she was enjoying school for the first time, feeding her curiosity about how the world worked. By 1940, with good grades and a pile of credits to her name, she was poised to earn a degree not from the School of General Studies, which was open to all, but from Barnard, Columbia University's distinguished college for women, the equivalent of Radcliffe at Harvard. To do so, however, she would have to take a few mandatory courses. Citing her lackluster high-school record, college officials told her she couldn't waive the requirements. Jane walked away in a huff and never looked back.

"Fortunately, my [high school] grades were so bad they wouldn't have me and I could continue to get an education," Jacobs said later-an education in the real world, that is. From that point on, Jacobs would scoff at academic credentials, rebuff universities seeking to give her honorary degrees, and refuse to be called an "expert" in print.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Girl from Scranton

As the rattling subway train slowed to a stop, Jane Butzner looked up to see the name of the station, its colorful lettering standing out against the white-tile station walls as it flashed by again and again, finally readable: Christopher Street/Sheridan Square. As the doors opened, she watched as a crowd poured out, moving past pretty mosaics to the exit.

She had moved to New York from her hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, and had joined her sister, Betty, in a small apartment in Brooklyn a few months before. She was hunting for a job, but the morning's interview had concluded swiftly, so she'd decided to explore her new city. She darted out before the doors slid shut and made her way through the turnstile and up a set of stairs to the street. Without knowing it, Jane had alighted in the heart of Greenwich Village, the place she would call home for decades to come.

As she emerged, she immediately noticed that the streets ran off at odd angles in all directions. She saw storefronts with awnings shading cluttered sidewalks, kids chasing one another in front of a grocery, delivery trucks stopping and starting their way up the street. Walking north on Seventh Avenue, she saw the skyscrapers of midtown in the distance and, when she turned around, the cluster of tall buildings in the financial district to the south. But in this spot most buildings were two or three stories, and few were higher than five or six. They were simple: no grand entrances, no soaring edifices. She gazed at shopwindows full of leather handbags and watches and jewelry, strolled past barbershops and cafés, and ran her fingers over the daily newspapers stacked high in front of shelves inside filled with candy and cigars. Everywhere she looked she saw people-people talking to one another, it seemed, every few feet, among them longshoremen headed to taverns at the end of their shifts, casually dressed women window-shopping, old men with hands clasped on canes sitting on the benches in a triangular park. Mothers sat on stoops watching over it all. Everyone looked, she thought, the way she felt: unpretentious, genuine, living their lives. This was home.

Arriving at her Brooklyn apartment that evening, Jane described the wonders of the neighborhood she had seen, concluding simply, "Betty, I found out where we have to live."

"Where is it?" Betty asked.

"I don't know, but you get in the subway and you get out at a place called Christopher Street."

Jane had moved to New York City in 1934. Armed with a high-school diploma, a recently acquired knowledge of shorthand, and the wisdom of a few months working in the newsroom of a Scranton newspaper, she hoped to break into journalism. She knew it wasn't going to be easy to succeed in a business dominated by men; her assignments in Scranton had been limited to covering weddings, social events, and the meetings of women's civic organizations with names like the Women of the Moose and the Ladies' Nest of Owls No. 3. It was the thick of the Great Depression, and any job was difficult to come by.

Her older sister, Betty, twenty-four, had warned her. Betty had come to New York a few years before with hopes of finding work as an interior designer, but was now grateful to have a job as a salesgirl in the home furnishings section of the Abraham & Straus department store. The headstrong Jane came to the big city anyway, joining her sister in the top floor of a six-floor walk-up in Brooklyn Heights, a neighborhood of Greek and Gothic Revival mansions and Italianate brownstones at the edge of the East River, overlooking Manhattan.

Within weeks of arriving, Jane realized that breaking into journalism was going to take time and that, in the meantime, she'd need to support herself. She began poring over employment agency listings looking for any clerical position she could find, and soon settled into a routine. Each morning she would walk from her apartment building, across the Brooklyn Bridge, and into lower Manhattan, where most of her interviews took place. The rest of her day would be spent exploring the city; she would invest a nickel for a subway ride and get out at random stops. She had been to New York only once before, as a girl of twelve, and now, at eighteen, she was drinking in the sights and sounds of a metropolis that could not be more different from Scranton.

Greenwich Village seemed to capture all the promise of moving to New York City for the young bespectacled girl from eastern Pennsylvania. As soon as she could, Jane brought her sister to Greenwich Village. Betty shared her enthusiasm for the neighborhood, and they quickly found an apartment on Morton Street, just south of the Christopher Street subway station. Morton Street was a classic Greenwich Village lane, running four blocks from east to west from the Hudson River, bending at a forty-five-degree angle in glorious violation of the orderly street grid of the rest of Manhattan. It was lined with petite trees, front-yard gardens, iron fences, and stately rows of four- and five-story brownstones and town houses.

Their neighbors there ranged from truckers and railway workers to artists, painters, and poets, including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and e. e. cummings. The White Horse Tavern, which for decades had been a gathering place for the bohemians of Greenwich Village, stood just around the corner on Hudson Street.

As excited as they were to be there, money was tight. After paying the rent, Jane and Betty had so little to spare that they resorted to mixing Pablum, a nutritious but notably bland cereal for infants, with milk for sustenance.

Their father's advice proved to be wise counsel in this time: that while the girls should pursue the careers of their dreams, they should also learn a practical skill to fall back on. The degree from the Powell secretarial and stenography school in Scranton gave Jane enough of an edge in the barren job market that after months of searching, she finally landed a job as a secretary for a candy manufacturing company. She would serve in similar clerical positions at a clock maker and a drapery hardware business in the years that followed. In her off time, she worked toward her dream career, honing her journalistic skills.

On those afternoons exploring the city after job interviews, and in her off-hours once she started working, she had begun writing down her observations of the city. In time she began to work them into articles. Early on she noticed that every few blocks of the city seemed to have a specialty trade-a little economy all their own. She sought to learn everything she could about these trades, striking up conversations with the shopkeepers and workers pushing racks of furs down the streets, and the leather makers in the deep back rooms into which she peered. Buckets of flowers on the sidewalk would prompt her to probe into the cut-flower trade; wandering through the diamond district on the Bowery on Manhattan's scrappy Lower East Side, she familiarized herself with the intricate system of jewelry auctions.

Immediately upon arriving home from work, she would toss her handbag on the sofa and settle in front of her manual typewriter in her room and write. After a while, she began to submit her pieces to popular magazines of the day. Much to her surprise, she arrived home one evening to find an envelope from an editor at Vogue who wanted to publish a story she had written on the fur district. The editors liked her plainspoken style and keen observations and wished to retain her as a freelance contributor. They proposed that she write four essays over the next two years, for which they would pay her $40 per article, a slightly better rate than the $12 per week she was making as a secretary. Her career as a writer in New York City had officially begun.

Her early journalism reflected an eye for the detail and the drama beneath the quotidian. A 1937 piece on the flower market in lower Manhattan, titled "Flowers Come to Town," began with a typical flourish:

All the ingredients of a lavender-and-old-lace love story, with a rip- roaring, contrasting background, are in New York's wholesale flower district, centered around Twenty-Eighth Street and Sixth Avenue. Under the melodramatic roar of the "El," encircled by hash-houses and Turkish baths, are the shops of hard-boiled, stalwart men, who shyly admit that they are dottles for love, sentiment, and romance.

She went on to describe in detail the 5:00 a.m. arrival of orchids, gardenias, peonies, and lilacs from Connecticut, Long Island, and New Jersey that were then meted out into buckets for sale by retailers. She considered the city's voracious demand for cut flowers and foliage-200 million ferns, 150,000 roses a day from just one grower in a season. It made sense when she thought about it: office reception areas, wedding receptions, society functions, and funerals all needed flowers. It was a big market, but the competition was fierce; she noted how the merchants adopted a set of rules to maintain a level playing field, such as agreeing not to open hampers in the flower market until 6:00 a.m., at the sound of a gong. She was fascinated not only with the mores of the city but with the way systems seemed to self-organize to prosper.

In another article, Jane wrote about the diamond district, which in the 1930s was centered on the Bowery across from the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. She described how the dealers in their beards and hats jotted down notes on the cut stones, rings, necklaces, and lockets that pawnbrokers had sent for display at auction, then made their bids with silent gestures or by squeezing the auctioneer's arm. "Upstairs, in the small light rooms over the stores, diamonds are cut and polished and set or re-set, and silver is buffed. The doors and vestibules to the rooms are barred and there is no superfluous furniture, just the tools and tables where the skillful workmen sit with leather hammocks to catch the chips and dust of diamond and metal," she wrote. "Silver is polished against a cloth-covered revolving wheel . . . All the sweepings are carefully saved to be refined and the silver recovered. The walls and ceilings are brushed and the old oilcloth coverings and work clothes of the men are burned to extract the silver dust. Even the water in which the workmen wash their hands is saved. A small room where silver is polished may yield to a refiner hundreds of dollars worth of metal a year." Outside, meanwhile, is the "lusty tumultuous life of the lower East Side"-the rumble of the elevated subway, "Chinamen from Mott Street," exotic aromas, and bums on the curbstones.

In those first years in New York, Jane worked forty hours a week, typing, filing, and taking dictation. All the while she continued to scout the far reaches of the city, writing for Vogue as well as other periodicals. On one outing she turned her attention to manhole covers, decoding their cryptic inscriptions in order to map the underground rivers of electricity and gas lines, the tributaries of brine to chill the storage areas of produce markets, and the pipes carrying steam to heat skyscrapers. Her account of this subterranean maze, which showed how urban life was made possible by what was underneath, appeared in a New York magazine called Cue, which primarily published theater and restaurant listings. She also wrote feature stories for the Sunday Herald Tribune.

She began to range beyond purely urban subjects, writing about the way fishing boats operated in Chesapeake Bay, the pagan origins of Christmas, and the decorative buttons on military uniform sleeves (originally meant to keep soldiers from using them to wipe their noses). She even tried her hand at short stories, in one piece depicting the decapitation of James Madison in a creative rewriting of American history-"bump, bump, bump" went the founding father's head on the floor, she wrote. An editor at Reader's Digest deemed the piece "too gruesome for us," and apparently other editors reacted in a similar fashion. Jacobs experimented with science fiction, too, writing a story about fast-growing plants with fantastical intentions that similarly went unsold.

But writing about the city remained her passion. She often went up to the rooftop of her apartment building and watched the garbage trucks as they made their way through the city streets, picking the sidewalks clean. She would think, "What a complicated great place this is, and all these pieces of it that make it work." The more she investigated and explored neighborhoods, infrastructure, and business districts for her stories, the more she began to see the city as a living, breathing thing-complex, wondrous, and self-perpetuating.

As she approached her fourth year in New York, Jane began to reconsider her opinion on higher education. It had become clear to her that she needed a boost to get a full-time job as a journalist. From a young age she had rebelled against what she viewed as the insipid curriculum of the Scranton schools, and scorned her teachers, whom she considered dim-witted. She was known to stick her tongue out when teachers' backs were turned and to challenge her teachers routinely. When a fourth-grade teacher claimed that cities formed only around rivers with waterfalls to provide electric power, Jane pointed out that Scranton had a waterfall but it had nothing to do with powering the city or the economy of the place. Another teacher asked her students to promise to brush their teeth every day. But Jane's father had just told her never to make a promise unless she was absolutely certain she could keep it. So she refused and urged her fellow students to do the same. The teacher kicked her out of the classroom, and Jane wandered along empty railroad tracks on her way home for lunch.

Now, in 1938, she used money from her parents to enroll at Columbia University's School of General Studies, more than a hundred blocks north of Greenwich Village, which had open enrollment for "nontraditional" students-those who had interrupted their education or needed to attend part-time. The school's lack of a set curriculum appealed to Jacobs.

At Columbia, she signed up for courses in any subject that interested her-chemistry, geography, geology, law, political science, psychology, and zoology. Before long she was enjoying school for the first time, feeding her curiosity about how the world worked. By 1940, with good grades and a pile of credits to her name, she was poised to earn a degree not from the School of General Studies, which was open to all, but from Barnard, Columbia University's distinguished college for women, the equivalent of Radcliffe at Harvard. To do so, however, she would have to take a few mandatory courses. Citing her lackluster high-school record, college officials told her she couldn't waive the requirements. Jane walked away in a huff and never looked back.

"Fortunately, my [high school] grades were so bad they wouldn't have me and I could continue to get an education," Jacobs said later-an education in the real world, that is. From that point on, Jacobs would scoff at academic credentials, rebuff universities seeking to give her honorary degrees, and refuse to be called an "expert" in print.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“The Jacobs/Moses war was educational, a living curriculum now encapsulated in Flint’s excellent study.”—The New York Review of Books

“[A] winning account . . . dramatically described . . . [Anthony] Flint looks at a seminal struggle of twentieth-century city planning, one that involved two giants with utterly differing views of how cities should look and develop.”—The Boston Globe

“[This book] shows how these mythic characters shaped each other’s work and reputations. . . . If there’s such a thing as beach reading for the urban studies set, it’s Wrestling with Moses.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“Lively and informative . . . Wrestling with Moses is about those who fought back against the power broker and in so doing helped set the stage for the city’s revitalization.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Well told . . . one of America’s greatest David and Goliath stories.”—The Hartford Courant

“[A] winning account . . . dramatically described . . . [Anthony] Flint looks at a seminal struggle of twentieth-century city planning, one that involved two giants with utterly differing views of how cities should look and develop.”—The Boston Globe

“[This book] shows how these mythic characters shaped each other’s work and reputations. . . . If there’s such a thing as beach reading for the urban studies set, it’s Wrestling with Moses.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“Lively and informative . . . Wrestling with Moses is about those who fought back against the power broker and in so doing helped set the stage for the city’s revitalization.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Well told . . . one of America’s greatest David and Goliath stories.”—The Hartford Courant

Premii

- Christopher Awards Winner, 2010