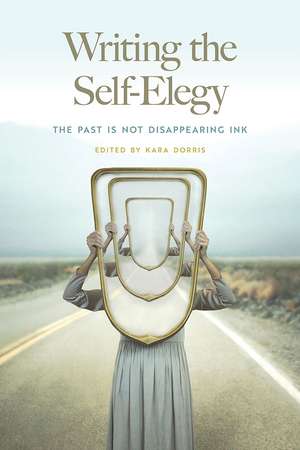

Writing the Self-Elegy: The Past Is Not Disappearing Ink

Editat de Kara Dorris Contribuţii de Teresa Leo, Jennifer McCauley, John Chavez, Katherine C. Jueds, Catherine Kyle, Adam Crittenden, Rigoberto Gonzalez, Kyle McCord, Jane Wong, Naomi Ortiz, Denise Leto, Carol Berg, Kristy Bowen, Floydd Michael Elliot, Jehanne Dubrow, Carl Phillips, Bruce Bond, Kevin Prufer, Rusane Morrison, Sheila Black, Lauren Shellberg, Anne Kaier, TC Tolbert, Raymond Luczak, Stephanie Heit, Juliet Cook, Tanaya Winderen Limba Engleză Paperback – 15 mai 2023

An innovative roadmap to facing our past and present selves

Honest, aching, and intimate, self-elegies are unique poems focusing on loss rather than death, mourning versions of the self that are forgotten or that never existed. Within their lyrical frame, multiple selves can coexist—wise and naïve, angry and resigned—along with multiple timelines, each possible path stemming from one small choice that both creates new selves and negates potential selves. Giving voice to pain while complicating personal truths, self-elegies are an ideal poetic form for our time, compelling us to question our close-minded certainties, heal divides, and rethink our relation to others.

In Writing the Self-Elegy, poet Kara Dorris introduces us to this prismatic tradition and its potential to forge new worlds. The self-elegies she includes in this anthology mix autobiography and poetics, blending craft with race, gender, sexuality, ability and disability, and place—all of the private and public elements that build individual and social identity. These poems reflect our complicated present while connecting us to our past, acting as lenses for understanding, and defining the self while facilitating reinvention. The twenty-eight poets included in this volume each practice self-elegy differently, realizing the full range of the form. In addition to a short essay that encapsulates the core value of the genre and its structural power, each poet’s contribution concludes with writing prompts that will be an inspiration inside the classroom and out. This is an anthology readers will keep close and share, exemplifying a style of writing that is as playful as it is interrogative and that restores the self in its confrontation with grief.

Honest, aching, and intimate, self-elegies are unique poems focusing on loss rather than death, mourning versions of the self that are forgotten or that never existed. Within their lyrical frame, multiple selves can coexist—wise and naïve, angry and resigned—along with multiple timelines, each possible path stemming from one small choice that both creates new selves and negates potential selves. Giving voice to pain while complicating personal truths, self-elegies are an ideal poetic form for our time, compelling us to question our close-minded certainties, heal divides, and rethink our relation to others.

In Writing the Self-Elegy, poet Kara Dorris introduces us to this prismatic tradition and its potential to forge new worlds. The self-elegies she includes in this anthology mix autobiography and poetics, blending craft with race, gender, sexuality, ability and disability, and place—all of the private and public elements that build individual and social identity. These poems reflect our complicated present while connecting us to our past, acting as lenses for understanding, and defining the self while facilitating reinvention. The twenty-eight poets included in this volume each practice self-elegy differently, realizing the full range of the form. In addition to a short essay that encapsulates the core value of the genre and its structural power, each poet’s contribution concludes with writing prompts that will be an inspiration inside the classroom and out. This is an anthology readers will keep close and share, exemplifying a style of writing that is as playful as it is interrogative and that restores the self in its confrontation with grief.

Preț: 288.94 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 433

Preț estimativ în valută:

55.29€ • 57.88$ • 45.75£

55.29€ • 57.88$ • 45.75£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809339068

ISBN-10: 0809339064

Pagini: 262

Dimensiuni: 152 x 235 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

ISBN-10: 0809339064

Pagini: 262

Dimensiuni: 152 x 235 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Notă biografică

Kara Dorris is an assistant professor of English at Illinois College and the author of When the Body is a Guardrail and Have Ruin, Will Travel.

Contributions by: Carol Berg, Lauren Berry, Sheila Black, Bruce Bond, Kristy Bowen, John Chavez, Juliet Cook, Adam Crittenden, Jehanne Dubrow, Floydd Michael Elliott, Rigoberto González, Stephanie Heit, Kasey Jueds, Anne Kaier, Catherine Kyle, Teresa Leo, Denise Leto, Raymond Luczak, Jennifer Maritza McCauley, Kyle McCord, Rusty Morrison, Naomi Ortiz, Carl Phillips, Kevin Prufer, T.C. Tolbert, Tanaya Winder, and Jane Wong.

Contributions by: Carol Berg, Lauren Berry, Sheila Black, Bruce Bond, Kristy Bowen, John Chavez, Juliet Cook, Adam Crittenden, Jehanne Dubrow, Floydd Michael Elliott, Rigoberto González, Stephanie Heit, Kasey Jueds, Anne Kaier, Catherine Kyle, Teresa Leo, Denise Leto, Raymond Luczak, Jennifer Maritza McCauley, Kyle McCord, Rusty Morrison, Naomi Ortiz, Carl Phillips, Kevin Prufer, T.C. Tolbert, Tanaya Winder, and Jane Wong.

Extras

HANDMADE INK (AN INTRODUCTION)

Today, in a time when “selfies” are popular, even leading to the invention of the “selfie stick,” it is not surprising that we would become more internally reflective while externally revealing our most personal desires. Historically, we have been trying to understand and share ourselves long before the invention of smart phones and filters—Narcissus staring at himself in water, bronze and silver-backed mirrors, artistic self-portraits by Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Kahlo, Sherman. Even the first recorded selfie, a daguerreotype taken in 1839, acts as a memorial and decorates its subject’s tombstone, American Robert Cornelius. Today, you can step into 3-D selfie machines, recreating and preserving an exact moment. An image is rarely just an image but a way of seeing, a reminder, a collection of choices and feelings that blend to create a singular experience. As long as we fear being forgotten, fear losing what we love, fear death, we will try to preserve, catalog, and share our lives. Familiar or not, this fear feels no less relevant.

Social media has made cataloging and sharing our lives even easier. When we add in the forced isolation of a global pandemic, hindsight and what-if possibilities, the fear of missing out becomes even more urgent. I wonder if we wrote notes for our pandemic selves, what would we say? Who were we before? Who will be after? That’s where the self-elegy comes in. To catalogue the good and bad, known and unknown, what could be or might never be.

For me, the self-elegy is reflective, reinventive, and confrontational, interrogating and elegizing past versions of self. To say self-elegy is new would be naive; as I read numerous elegies, from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 71 to Laura Kasischke’s “Space, in Chains,” I found moments of self-elegizing—for how can we truly mourn another without mourning the self created through that relationship? Yet, this awareness of self (and how the self is created) seems more prevalent than ever before. With self in the description, when the self is often considered an individualized construct, does a self-elegy have to only mourn the self or an aspect of the self to be classified as a self-elegy? And if so, why would we want to impose such a limitation?

Sometimes I think comparing contemporary self-elegies to selfies is a brilliant strategy; other times, an oversimplification or even wishful thinking—both are cultural artifacts stemming from a time of accessibility, excess, and reflection; both serve as remembrances allowing us to revisit past moments; both have the potential to promote agency, urging us to control and share our own narratives even as these same mediums shape those narratives and perceptions.

At its core, isn’t a selfie an artifact, a memorial of a moment gone too fast, a moment to remember, to celebrate, and ultimately mourn? Proof of a self already changing? A want? A wish? Then again, perhaps I am looking only as a poet looks at the world and sees an opportunity to stage, to reflect, to understand. Which leads us to primary motivations behind selfies and, arguably, behind self-elegies as well: defining and framing our own self-creation myths. The question is: are selfies isolationist narcissism or building blocks for self and community? Are we trying to present a false, superficial perfection, consciously or not, or are we genuinely trying to share our truest selves, warts and all? One prevents connection, the other welcomes it. And does it have to be one or the other? Let’s look at my story.

Can you remember your first time? My first selfie, that I remember consciously setting out to take, was standing before the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum. It’s 2001, and I’m 20 years old wearing jeans, Diesel shoes, and an orange tank top. My long reddish-brown hair pulled up on a messy bun. The camera is held tight against my face, my reflection reflected in glass, superimposed over stone. I wanted proof that I existed in that particular space and time. In the picture, I am more prominent than the stone, but the stone as a translation miracle informed my need to mark the moment. Without the stone, I wouldn’t have stopped to take the picture. Without the glass case, my image wouldn’t even have been captured, which, I guess was the point: without knowing it, I was already framing my body to hide my disability. Seven years later, I wrote my first self-elegy, “Osteochondroma Lineage,” even if I didn’t know it at the time, which traced the influence my hereditary bone disorder has had on my life as a way of seeing, of understanding. By writing this poem, I was better able to understand how my bone disorder frames my experiences, past and present.

Self-elegies can allow poets to question without expectation of clear answers, to analyze the self bluntly without a coat of sugar, to be angry and melancholic at the inevitable loss time offers us. The past has a finality of death—we cannot change it—only try to understand how it influences today and tomorrow. My identity as a mourner, as one who was born to lose everything—emotionally and physically—defines me. Self-elegy allows me to define myself, create my own rehearsal space where I can dance between loss and self-reinvention—and hopefully afterwards, I will understand the world better and my place in it. I will understand that disability is not shameful and does not make us less. I am not a dancer, but the dream of being one still defines me, as does the story about a failed typing class, as well as the retelling of that story in these pages. So, yes, I mourn versions of myself that never existed or versions left behind. I mourn that wannabe dancer who never knew genetics outweigh determination. Why not just bury those dead versions of myself? I need those versions like I need my left radial bone or intestines. It’s all integral. All vital. Physical and mental skeleton and viscera. If I wrote a self-elegy to my fifteen-year-old self I would say the self is multiple and contradictory, a fickle mystery we continuously try to unravel. So what if you hold your left elbow out like an arabesque when you type? You won’t know it is wrong until someone tells you. You will lose something that day. Don’t waste every day after chasing it. Of course, she probably wouldn’t have listened, but I’m listening now.

[end of excerpt]

Today, in a time when “selfies” are popular, even leading to the invention of the “selfie stick,” it is not surprising that we would become more internally reflective while externally revealing our most personal desires. Historically, we have been trying to understand and share ourselves long before the invention of smart phones and filters—Narcissus staring at himself in water, bronze and silver-backed mirrors, artistic self-portraits by Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Kahlo, Sherman. Even the first recorded selfie, a daguerreotype taken in 1839, acts as a memorial and decorates its subject’s tombstone, American Robert Cornelius. Today, you can step into 3-D selfie machines, recreating and preserving an exact moment. An image is rarely just an image but a way of seeing, a reminder, a collection of choices and feelings that blend to create a singular experience. As long as we fear being forgotten, fear losing what we love, fear death, we will try to preserve, catalog, and share our lives. Familiar or not, this fear feels no less relevant.

Social media has made cataloging and sharing our lives even easier. When we add in the forced isolation of a global pandemic, hindsight and what-if possibilities, the fear of missing out becomes even more urgent. I wonder if we wrote notes for our pandemic selves, what would we say? Who were we before? Who will be after? That’s where the self-elegy comes in. To catalogue the good and bad, known and unknown, what could be or might never be.

For me, the self-elegy is reflective, reinventive, and confrontational, interrogating and elegizing past versions of self. To say self-elegy is new would be naive; as I read numerous elegies, from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 71 to Laura Kasischke’s “Space, in Chains,” I found moments of self-elegizing—for how can we truly mourn another without mourning the self created through that relationship? Yet, this awareness of self (and how the self is created) seems more prevalent than ever before. With self in the description, when the self is often considered an individualized construct, does a self-elegy have to only mourn the self or an aspect of the self to be classified as a self-elegy? And if so, why would we want to impose such a limitation?

Sometimes I think comparing contemporary self-elegies to selfies is a brilliant strategy; other times, an oversimplification or even wishful thinking—both are cultural artifacts stemming from a time of accessibility, excess, and reflection; both serve as remembrances allowing us to revisit past moments; both have the potential to promote agency, urging us to control and share our own narratives even as these same mediums shape those narratives and perceptions.

At its core, isn’t a selfie an artifact, a memorial of a moment gone too fast, a moment to remember, to celebrate, and ultimately mourn? Proof of a self already changing? A want? A wish? Then again, perhaps I am looking only as a poet looks at the world and sees an opportunity to stage, to reflect, to understand. Which leads us to primary motivations behind selfies and, arguably, behind self-elegies as well: defining and framing our own self-creation myths. The question is: are selfies isolationist narcissism or building blocks for self and community? Are we trying to present a false, superficial perfection, consciously or not, or are we genuinely trying to share our truest selves, warts and all? One prevents connection, the other welcomes it. And does it have to be one or the other? Let’s look at my story.

Can you remember your first time? My first selfie, that I remember consciously setting out to take, was standing before the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum. It’s 2001, and I’m 20 years old wearing jeans, Diesel shoes, and an orange tank top. My long reddish-brown hair pulled up on a messy bun. The camera is held tight against my face, my reflection reflected in glass, superimposed over stone. I wanted proof that I existed in that particular space and time. In the picture, I am more prominent than the stone, but the stone as a translation miracle informed my need to mark the moment. Without the stone, I wouldn’t have stopped to take the picture. Without the glass case, my image wouldn’t even have been captured, which, I guess was the point: without knowing it, I was already framing my body to hide my disability. Seven years later, I wrote my first self-elegy, “Osteochondroma Lineage,” even if I didn’t know it at the time, which traced the influence my hereditary bone disorder has had on my life as a way of seeing, of understanding. By writing this poem, I was better able to understand how my bone disorder frames my experiences, past and present.

Self-elegies can allow poets to question without expectation of clear answers, to analyze the self bluntly without a coat of sugar, to be angry and melancholic at the inevitable loss time offers us. The past has a finality of death—we cannot change it—only try to understand how it influences today and tomorrow. My identity as a mourner, as one who was born to lose everything—emotionally and physically—defines me. Self-elegy allows me to define myself, create my own rehearsal space where I can dance between loss and self-reinvention—and hopefully afterwards, I will understand the world better and my place in it. I will understand that disability is not shameful and does not make us less. I am not a dancer, but the dream of being one still defines me, as does the story about a failed typing class, as well as the retelling of that story in these pages. So, yes, I mourn versions of myself that never existed or versions left behind. I mourn that wannabe dancer who never knew genetics outweigh determination. Why not just bury those dead versions of myself? I need those versions like I need my left radial bone or intestines. It’s all integral. All vital. Physical and mental skeleton and viscera. If I wrote a self-elegy to my fifteen-year-old self I would say the self is multiple and contradictory, a fickle mystery we continuously try to unravel. So what if you hold your left elbow out like an arabesque when you type? You won’t know it is wrong until someone tells you. You will lose something that day. Don’t waste every day after chasing it. Of course, she probably wouldn’t have listened, but I’m listening now.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

CONTENTS

Handmade Ink (An Introduction)

Agency: The Framing Effect

Teresa Leo

Jennifer Maritza McCauley

John Chavez

Kasey Jueds

Catherine Kyle

Adam Crittenden

Rigoberto González

Kyle McCord

Jane Wong

Naomi Ortiz

Multiplicity: Multiple Timelines and Selves

Denise Leto

Carol Berg

Kristy Bowen

Floydd Michael Elliott

Kara Dorris

Jehanne Dubrow

Carl Phillips

Bruce Bond

Kevin Prufer

Other: Defining Self through the External

Rusty Morrison

Sheila Black

Lauren Berry

Anne Kaier

TC Tolbert

Raymond Luczak

Stephanie Heit

Juliet Cook

Tanaya Winder

Contributor Bios

Acknowledgments

Handmade Ink (An Introduction)

Agency: The Framing Effect

Teresa Leo

Jennifer Maritza McCauley

John Chavez

Kasey Jueds

Catherine Kyle

Adam Crittenden

Rigoberto González

Kyle McCord

Jane Wong

Naomi Ortiz

Multiplicity: Multiple Timelines and Selves

Denise Leto

Carol Berg

Kristy Bowen

Floydd Michael Elliott

Kara Dorris

Jehanne Dubrow

Carl Phillips

Bruce Bond

Kevin Prufer

Other: Defining Self through the External

Rusty Morrison

Sheila Black

Lauren Berry

Anne Kaier

TC Tolbert

Raymond Luczak

Stephanie Heit

Juliet Cook

Tanaya Winder

Contributor Bios

Acknowledgments

Recenzii

“In this anthology, poets mourn the selves they used to be or never became. While some interrogate and confront, others introspect and reflect on those lost selves. Whether it's a memorialized moment or a choice that pivoted a life, each of these voices is listening to the past and speaking back to it.”—Traci Brimhall, author ofCome the Slumberless to the Land of Nod

“‘What if?’ This is the question that productively drives this engagement with the self-elegy: somewhere between dream and selfie; with bodyminds shifted, twisted and nailed. The poets in this book engage their form with elegance and ultimate joy in their acts of creation. They also invite you into their fold: each poet offers prompts to the reader, as well as essayistic thoughts, de-mystifying and re-mystifying these acts of (inter)corporeal magic.”—Petra Kuppers, author of Gut Botany + Eco Soma: Pain and Joy in Speculative Performance Encounters

"Underscoring 'agency,' 'multiplicity,' and 'other,' a trifecta of inter-related themes that remain central to a broad array of negotiating Disability experiences—both individual and collective—the 28 poets in this iconoclastic new volume edited by Kara Dorris bring the self-eulogy into palpable distinction for a new generation of readers and writers. Negotiating temporal transformation while centering body-mindedness, authors both emergent and well-known cohabitate to contribute boldly to a global and local burgeoning Disability and Crip poetics movement. Writing the Self-Elegy is an aching palimpsest, a vibrant hologram, and an uneasy anthem that unapologetically defies categorization with its secular grace. I trust this book—including its badass triumph over inspo-porn—will find accessible homes and meaningful engagement in imaginations, conversations, and classrooms everywhere."—Diane R. Wiener, author of The Golem Verses, Flashes Specks, and The Golem Returns, and Editor-in-Chief of Wordgathering: A Journal of Disability Poetry and Literature

“‘What if?’ This is the question that productively drives this engagement with the self-elegy: somewhere between dream and selfie; with bodyminds shifted, twisted and nailed. The poets in this book engage their form with elegance and ultimate joy in their acts of creation. They also invite you into their fold: each poet offers prompts to the reader, as well as essayistic thoughts, de-mystifying and re-mystifying these acts of (inter)corporeal magic.”—Petra Kuppers, author of Gut Botany + Eco Soma: Pain and Joy in Speculative Performance Encounters

"Underscoring 'agency,' 'multiplicity,' and 'other,' a trifecta of inter-related themes that remain central to a broad array of negotiating Disability experiences—both individual and collective—the 28 poets in this iconoclastic new volume edited by Kara Dorris bring the self-eulogy into palpable distinction for a new generation of readers and writers. Negotiating temporal transformation while centering body-mindedness, authors both emergent and well-known cohabitate to contribute boldly to a global and local burgeoning Disability and Crip poetics movement. Writing the Self-Elegy is an aching palimpsest, a vibrant hologram, and an uneasy anthem that unapologetically defies categorization with its secular grace. I trust this book—including its badass triumph over inspo-porn—will find accessible homes and meaningful engagement in imaginations, conversations, and classrooms everywhere."—Diane R. Wiener, author of The Golem Verses, Flashes Specks, and The Golem Returns, and Editor-in-Chief of Wordgathering: A Journal of Disability Poetry and Literature

Descriere

In Writing the Self-Elegy, poet Kara Dorris introduces us to the prismatic poetic tradition of self-elegy and its potential to forge new worlds. The twenty-eight poets featured in this anthology mix autobiography and poetics, blending craft with race, gender, sexuality, ability and disability, and place—all of the private and public elements that build individual and social identity.