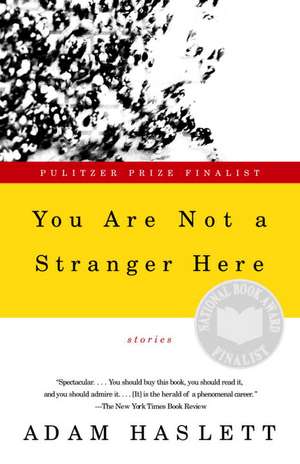

You Are Not a Stranger Here

Autor Adam Hasletten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2003

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

National Book Awards (2002)

An elderly inventor, burning with manic creativity, tries to reconcile with his estranged gay son. A bereaved boy draws a thuggish classmate into a relationship of escalating guilt and violence. A genteel middle-aged woman, a long-time resident of a psychiatric hospital, becomes the confidante of a lovelorn teenaged volunteer. Told with Chekhovian restraint and compassion, and conveying both the sorrow of life and the courage with which people rise to meet it, You Are Not a Stranger Here is a triumph of storytelling.

Preț: 78.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 117

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.98€ • 15.43$ • 12.64£

14.98€ • 15.43$ • 12.64£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385720724

ISBN-10: 0385720726

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385720726

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Adam Haslett is the author of You Are Not A Stranger Here, a short story collection, which was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award, and won the PEN/Winship Award. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Nation, Zoetrope, and Best American Short Stories as well as National Public Radio’s Selected Shorts. He is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and the Yale Law school and has received fellowships from the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center and the Michener/Copernicus Society of America. He lives in New York City, where he works part-time as a legal consultant.

Extras

Notes to My Biographer

Two things to get straight from the beginning: I hate doctors and have never joined a support group in my life. At seventy-three, I'm not about to change. The mental health establishment can go screw itself on a barren hill top in the rain before I touch their snake oil or listen to the visionless chatter of men half my age. I have shot Germans in the fields of Normandy, filed twenty-six patents, married three women, survived them all and am currently the subject of an investigation by the IRS, which has about as much chance of collecting from me as Shylock did of getting his pound of flesh. Bureaucracies have trouble thinking clearly. I, on the other hand, am perfectly lucid.

Note for instance how I obtained the Saab I'm presently driving into the Los Angeles basin: a niece in Scotsdale lent it to me. Do you think she'll ever see it again? Unlikely. Of course when I borrowed it from her I had every intention of returning it and in a few days or weeks I may feel that way again, but for now forget her and her husband and three children who looked at me over the kitchen table like I was a museum piece sent to bore them. I could run circles around those kids. They're spoon fed ritalin and private schools and have eyes that say give me things I don't have. I wanted to read them a book on the history of the world, its migrations, plagues, and wars, but the shelves of their outsized condominium were full of ceramics and biographies of the stars. The whole thing depressed the hell out of me and I'm glad to be gone.

A week ago I left Baltimore with the idea of seeing my son Graham. I've been thinking about him a lot recently, days we spent together in the barn at the old house, how with him as my audience ideas came quickly and I don't know when I'll get to see him again. I thought I might as well catch up with some of the other relatives along the way and planned to start at my daughter Linda's in Atlanta but when I arrived it turned out she'd moved. I called Graham and when he got over the shock of hearing my voice, he said Linda didn't want to see me. By the time my younger brother Ernie refused to do anything more than have lunch with me after I'd taken a bus all the way to Houston, I began to get the idea this episodic reunion thing might be more trouble than it was worth. Scotsdale did nothing to alter my opinion. These people seem to think they'll have another chance, that I'll be coming around again. The fact is I've completed my will, made bequests of my patent rights, and am now just composing a few notes to my biographer who, in a few decades when the true influence of my work becomes apparent, may need them to clarify certain issues.

*Franklin Caldwell Singer, b.1924, Baltimore, Maryland.

*Child of a German machinist and a banker's daughter.

*My psych discharge following "desertion" in Paris was trumped up by an army intern resentful of my superior knowledge of the diagnostic manual. The nude dancing incident at the Louvre in a room full of Rubens had occurred weeks earlier and was of a piece with other celebrations at the time.

*BA, PhD Engineering, Johns Hopkins University.

*1952. First and last electro-shock treatment for which I will never, never, never forgive my parents.

*1954-1965 Researcher, Eastman Kodak Laboratories. As with so many institutions in this country, talent was resented. I was fired as soon as I began to point out flaws in the management structure. Two years later I filed a patent on a shutter mechanism that Kodak eventually broke down and purchased (then Vice-President for Product Development, Arch Vendellini WAS having an affair with his daughter's best friend, contrary to what he will tell you. Notice the way his left shoulder twitches when he's lying).

*All subsequent diagnoses--and let me tell you there have been a number--are the result of two forces, both in their way pernicious. 1) The attempt by the psychiatric establishment over the last century to redefine eccentricity as illness, and 2) the desire of members of my various families to render me docile and if possible immobile.

*The electric bread slicer concept was stolen from me by a man in a diner in Chevy Chase dressed as a reindeer whom I could not possibly have known was an employee of Westinghouse.

*That I have no memories of the years 1988-90 and believed until very recently that Ed Meese was still the Attorney General is not owing to my purported paranoid black-out but on the contrary to the fact my third wife took it upon herself to lace my coffee with tranquilizers. Believe nothing you hear about the divorce settlement.

When I ring the buzzer at Graham's place in Venice, a Jew in his late twenties with some fancy looking musculature answers the door. He appears nervous and says, "We weren't expecting you 'til tomorrow," and I ask him who we are and he says, "Me and Graham," adding hurriedly, "we're friends, you know, only friends. I don't live here, I'm just over to use the computer."

All I can think is I hope this guy isn't out here trying to get acting jobs, because it's obvious to me right away that my son is gay and is screwing this character with the expensive looking glasses. There was a lot of that in the military and I learned early on that it comes in all shapes and sizes, not just the fairy types everyone expects. Nonetheless, I am briefly shocked by the idea that my twenty-nine year old boy has never seen fit to share with me the fact that he is a fruitcake--no malice intended--and I resolve right away to talk to him about it when I see him. Marlon Brando overcomes his stupor and lifting my suitcase from the car leads me through the back garden past a lemon tree in bloom to a one room cottage with a sink and plenty of light to which I take an instant liking.

"This will do nicely," I say and then I ask him, "How long have you been sleeping with my son?" It's obvious he thinks I'm some brand of geriatric homophobe getting ready to come on in a religiously heavy manner and seeing that deer-caught-in-the-headlights look in his eye I take pity and disabuse him. I've seen women run down by tanks. I'm not about to get worked up about the prospect of fewer grandchildren. When I start explaining to him that social prejudice of all stripes runs counter to my Enlightenment ideals--ideals tainted by centuries of partial application--it becomes clear to me that Graham has given him the family line. His face grows patient and his smile begins to leak the sympathy of the ignorant: poor old guy suffering from mental troubles his whole life, up one month, down the next, spewing grandiose notions that slip like sand through his fingers to which I always say, you just look up Frank Singer at the U.S. Patent Office. In any case, this turkey probably thinks the Enlightenment is a marketing scheme for General Electric; I spare him the seminar I could easily conduct and say, "Look, if the two of you share a bed, it's fine with me."

"That drive must have worn you out," he says hopefully. "Do you want to lie down for a bit?"

I tell him I could hook a chain to my niece's Saab and drag it through a marathon. This leaves him nonplussed. We walk back across the yard together into the kitchen of the bungalow. I ask him for pen, paper, and a calculator and begin sketching an idea that came to me just a moment ago--I can feel the presence of Graham already--for a bicycle capable of storing the energy generated on the downward slope in a small battery and releasing it through a handle bar control when needed on the up hill--a potential gold mine when you consider the aging population and the increase in leisure time created by early retirement. I have four pages of specs and the estimated cost of a prototype done by the time Graham arrives two hours later. He walks into the kitchen wearing a blue linen suit, a briefcase held to his chest, and seeing me at the table goes stiff as a board. I haven't seen him in five years and the first thing I notice is that he's got bags under his eyes. When I open my arms to embrace him he takes a step backwards.

"What's the matter?" I ask. Here is my child wary of me in a strange kitchen in California, his mother's ashes spread long ago over the Potomac, the objects of our lives together stored in boxes or sold.

"You actually came," he says.

"I've invented a new bicycle," I say but this seems to reach him like news of some fresh death. Eric hugs Graham there in front of me. I watch my son rest his head against this fellow's shoulder like a tired solider on a train. "It's going to have a self-charging battery," I say sitting again at the table to review my sketches.

With Graham here my idea is picking up speed and while he's in the shower I unpack my bags, rearrange the furniture in the cottage, and tack my specs to the wall. Returning to the house, I ask Eric if I can use the phone and he says that's fine and then he tells me, "Graham hasn't been sleeping so great lately, but I know he really does want to see you."

"Sure no hard feelings fine."

"He's been dealing with a lot recently. Maybe some things you could talk to him about . . . and I think you might--"

"Sure, sure no hard feelings," and then I call my lawyer, my engineer, my model builder, three advertising firms whose numbers I find in the yellow pages, the American Association of Retired Persons--that market will be key, an old college friend whom I remember once told me he'd competed in the Tour de France figuring he'll know the bicycle industry angle, my bank manager to discuss financing, the Patent Office, the Cal Tech physics lab, the woman I took to dinner the week before I left Baltimore and three local liquor stores before I find one that will deliver a case of Don Perignon.

"That'll be for me!" I call out to Graham as he emerges from the bedroom to answer the door what seems only minutes later. He moves slowly and seems sapped of life.

"What's this?"

"We're celebrating! There's a new project in the pipeline!"

Graham stares at the bill as though he's having trouble reading it. Finally, he says, "This is twelve-hundred dollars. We're not buying it."

I tell him Schwinn will drop that on donuts for the sales reps when I'm done with this bike, that Ophra Winfrey's going to ride it through the half-time show at the Super Bowl.

"There's been a mistake," he says to the delivery guy.

I end up having to go outside and pay for it through the window of the truck with a credit card the man is naive enough to except and I carry it back to the house myself.

"What am I going to do?" I hear Graham whisper.

I round the corner in to the kitchen and they fall silent. The two of them make a handsome couple standing there in the gauzy, expiring light of evening. When I was born you could have arrested them for kissing. There ensues an argument that I only half bother to participate in concerning the champagne and my enthusiasm, a recording he learned from his mother; he presses play and the fraction of his ancestry that suffered from conventionalism speaks through his mouth like a ventriloquist: your-idea-is-fantasy-calm-down-it-will-be-the-ruin-of-you-medication-medicat ion-medication. He has a good mind my son, always has, and somewhere the temerity to use it, to spear mediocrity in the eye, but in a world that encourages nothing of the sort the curious boy becomes the anxious man. He must suffer his people's regard for appearances. Sad. I begin to articulate this with Socratic lucidity, which seems only to exacerbate the situation.

"Why don't we just have some champagne," Eric interjects. "You two can talk this over at dinner."

An admirable suggestion. I take three glasses from the cupboard, remove a bottle from the case, pop the cork, fill the glasses and propose a toast to their health.

My niece's Saab does eighty-five without a shudder on the way to dinner. With the roof down, smog blowing through my hair, I barely hear Graham who's shouting something from the passenger's seat. He's probably worried about a ticket, which for the high of this ride I'd pay twice over and tip the officer to boot. Sailing down the freeway I envision a lane of bicycles quietly recycling efficiencies once lost to the simple act of pedaling. We'll have to get the environmentalists involved which could mean government money for research and a lobbying arm to navigate any legislative interference. Test marketing in L.A. will increase the chance of celebrity endorsements and I'll probably need to do a book on the germination of the idea for release with the first wave of product. I'm thinking early 2003. The advertising tag line hits me as we glide beneath an overpass: Make Every Revolution Count.

There's a line at the restaurant and when I try to slip the maitre'd a twenty, Graham holds me back.

"Dad," he says, "you can't do that."

"Remember the time I took you to the Ritz and you told me the chicken in your sandwich was tough and I spoke to the manager and we got the meal for free? And you drew a diagram of the tree fort you wanted and it gave me an idea for storage containers."

He nods his head.

"Come on, where's your smile?"

I walk up to the maitre'd but when I hand him the twenty he gives me a funny look and I tell him he's a lousy shit for pretending he's above that sort of thing. "You want a hundred?" I ask and am about to give him an even larger piece of my mind when Graham turns me around and says, "Please don't."

"What kind of work are you doing?" I ask him.

"Dad," he says, "just settle down." His voice is so quiet, so meek.

"I asked you what kind of work you do?"

"I work at a brokerage."

From the Hardcover edition.

Two things to get straight from the beginning: I hate doctors and have never joined a support group in my life. At seventy-three, I'm not about to change. The mental health establishment can go screw itself on a barren hill top in the rain before I touch their snake oil or listen to the visionless chatter of men half my age. I have shot Germans in the fields of Normandy, filed twenty-six patents, married three women, survived them all and am currently the subject of an investigation by the IRS, which has about as much chance of collecting from me as Shylock did of getting his pound of flesh. Bureaucracies have trouble thinking clearly. I, on the other hand, am perfectly lucid.

Note for instance how I obtained the Saab I'm presently driving into the Los Angeles basin: a niece in Scotsdale lent it to me. Do you think she'll ever see it again? Unlikely. Of course when I borrowed it from her I had every intention of returning it and in a few days or weeks I may feel that way again, but for now forget her and her husband and three children who looked at me over the kitchen table like I was a museum piece sent to bore them. I could run circles around those kids. They're spoon fed ritalin and private schools and have eyes that say give me things I don't have. I wanted to read them a book on the history of the world, its migrations, plagues, and wars, but the shelves of their outsized condominium were full of ceramics and biographies of the stars. The whole thing depressed the hell out of me and I'm glad to be gone.

A week ago I left Baltimore with the idea of seeing my son Graham. I've been thinking about him a lot recently, days we spent together in the barn at the old house, how with him as my audience ideas came quickly and I don't know when I'll get to see him again. I thought I might as well catch up with some of the other relatives along the way and planned to start at my daughter Linda's in Atlanta but when I arrived it turned out she'd moved. I called Graham and when he got over the shock of hearing my voice, he said Linda didn't want to see me. By the time my younger brother Ernie refused to do anything more than have lunch with me after I'd taken a bus all the way to Houston, I began to get the idea this episodic reunion thing might be more trouble than it was worth. Scotsdale did nothing to alter my opinion. These people seem to think they'll have another chance, that I'll be coming around again. The fact is I've completed my will, made bequests of my patent rights, and am now just composing a few notes to my biographer who, in a few decades when the true influence of my work becomes apparent, may need them to clarify certain issues.

*Franklin Caldwell Singer, b.1924, Baltimore, Maryland.

*Child of a German machinist and a banker's daughter.

*My psych discharge following "desertion" in Paris was trumped up by an army intern resentful of my superior knowledge of the diagnostic manual. The nude dancing incident at the Louvre in a room full of Rubens had occurred weeks earlier and was of a piece with other celebrations at the time.

*BA, PhD Engineering, Johns Hopkins University.

*1952. First and last electro-shock treatment for which I will never, never, never forgive my parents.

*1954-1965 Researcher, Eastman Kodak Laboratories. As with so many institutions in this country, talent was resented. I was fired as soon as I began to point out flaws in the management structure. Two years later I filed a patent on a shutter mechanism that Kodak eventually broke down and purchased (then Vice-President for Product Development, Arch Vendellini WAS having an affair with his daughter's best friend, contrary to what he will tell you. Notice the way his left shoulder twitches when he's lying).

*All subsequent diagnoses--and let me tell you there have been a number--are the result of two forces, both in their way pernicious. 1) The attempt by the psychiatric establishment over the last century to redefine eccentricity as illness, and 2) the desire of members of my various families to render me docile and if possible immobile.

*The electric bread slicer concept was stolen from me by a man in a diner in Chevy Chase dressed as a reindeer whom I could not possibly have known was an employee of Westinghouse.

*That I have no memories of the years 1988-90 and believed until very recently that Ed Meese was still the Attorney General is not owing to my purported paranoid black-out but on the contrary to the fact my third wife took it upon herself to lace my coffee with tranquilizers. Believe nothing you hear about the divorce settlement.

When I ring the buzzer at Graham's place in Venice, a Jew in his late twenties with some fancy looking musculature answers the door. He appears nervous and says, "We weren't expecting you 'til tomorrow," and I ask him who we are and he says, "Me and Graham," adding hurriedly, "we're friends, you know, only friends. I don't live here, I'm just over to use the computer."

All I can think is I hope this guy isn't out here trying to get acting jobs, because it's obvious to me right away that my son is gay and is screwing this character with the expensive looking glasses. There was a lot of that in the military and I learned early on that it comes in all shapes and sizes, not just the fairy types everyone expects. Nonetheless, I am briefly shocked by the idea that my twenty-nine year old boy has never seen fit to share with me the fact that he is a fruitcake--no malice intended--and I resolve right away to talk to him about it when I see him. Marlon Brando overcomes his stupor and lifting my suitcase from the car leads me through the back garden past a lemon tree in bloom to a one room cottage with a sink and plenty of light to which I take an instant liking.

"This will do nicely," I say and then I ask him, "How long have you been sleeping with my son?" It's obvious he thinks I'm some brand of geriatric homophobe getting ready to come on in a religiously heavy manner and seeing that deer-caught-in-the-headlights look in his eye I take pity and disabuse him. I've seen women run down by tanks. I'm not about to get worked up about the prospect of fewer grandchildren. When I start explaining to him that social prejudice of all stripes runs counter to my Enlightenment ideals--ideals tainted by centuries of partial application--it becomes clear to me that Graham has given him the family line. His face grows patient and his smile begins to leak the sympathy of the ignorant: poor old guy suffering from mental troubles his whole life, up one month, down the next, spewing grandiose notions that slip like sand through his fingers to which I always say, you just look up Frank Singer at the U.S. Patent Office. In any case, this turkey probably thinks the Enlightenment is a marketing scheme for General Electric; I spare him the seminar I could easily conduct and say, "Look, if the two of you share a bed, it's fine with me."

"That drive must have worn you out," he says hopefully. "Do you want to lie down for a bit?"

I tell him I could hook a chain to my niece's Saab and drag it through a marathon. This leaves him nonplussed. We walk back across the yard together into the kitchen of the bungalow. I ask him for pen, paper, and a calculator and begin sketching an idea that came to me just a moment ago--I can feel the presence of Graham already--for a bicycle capable of storing the energy generated on the downward slope in a small battery and releasing it through a handle bar control when needed on the up hill--a potential gold mine when you consider the aging population and the increase in leisure time created by early retirement. I have four pages of specs and the estimated cost of a prototype done by the time Graham arrives two hours later. He walks into the kitchen wearing a blue linen suit, a briefcase held to his chest, and seeing me at the table goes stiff as a board. I haven't seen him in five years and the first thing I notice is that he's got bags under his eyes. When I open my arms to embrace him he takes a step backwards.

"What's the matter?" I ask. Here is my child wary of me in a strange kitchen in California, his mother's ashes spread long ago over the Potomac, the objects of our lives together stored in boxes or sold.

"You actually came," he says.

"I've invented a new bicycle," I say but this seems to reach him like news of some fresh death. Eric hugs Graham there in front of me. I watch my son rest his head against this fellow's shoulder like a tired solider on a train. "It's going to have a self-charging battery," I say sitting again at the table to review my sketches.

With Graham here my idea is picking up speed and while he's in the shower I unpack my bags, rearrange the furniture in the cottage, and tack my specs to the wall. Returning to the house, I ask Eric if I can use the phone and he says that's fine and then he tells me, "Graham hasn't been sleeping so great lately, but I know he really does want to see you."

"Sure no hard feelings fine."

"He's been dealing with a lot recently. Maybe some things you could talk to him about . . . and I think you might--"

"Sure, sure no hard feelings," and then I call my lawyer, my engineer, my model builder, three advertising firms whose numbers I find in the yellow pages, the American Association of Retired Persons--that market will be key, an old college friend whom I remember once told me he'd competed in the Tour de France figuring he'll know the bicycle industry angle, my bank manager to discuss financing, the Patent Office, the Cal Tech physics lab, the woman I took to dinner the week before I left Baltimore and three local liquor stores before I find one that will deliver a case of Don Perignon.

"That'll be for me!" I call out to Graham as he emerges from the bedroom to answer the door what seems only minutes later. He moves slowly and seems sapped of life.

"What's this?"

"We're celebrating! There's a new project in the pipeline!"

Graham stares at the bill as though he's having trouble reading it. Finally, he says, "This is twelve-hundred dollars. We're not buying it."

I tell him Schwinn will drop that on donuts for the sales reps when I'm done with this bike, that Ophra Winfrey's going to ride it through the half-time show at the Super Bowl.

"There's been a mistake," he says to the delivery guy.

I end up having to go outside and pay for it through the window of the truck with a credit card the man is naive enough to except and I carry it back to the house myself.

"What am I going to do?" I hear Graham whisper.

I round the corner in to the kitchen and they fall silent. The two of them make a handsome couple standing there in the gauzy, expiring light of evening. When I was born you could have arrested them for kissing. There ensues an argument that I only half bother to participate in concerning the champagne and my enthusiasm, a recording he learned from his mother; he presses play and the fraction of his ancestry that suffered from conventionalism speaks through his mouth like a ventriloquist: your-idea-is-fantasy-calm-down-it-will-be-the-ruin-of-you-medication-medicat ion-medication. He has a good mind my son, always has, and somewhere the temerity to use it, to spear mediocrity in the eye, but in a world that encourages nothing of the sort the curious boy becomes the anxious man. He must suffer his people's regard for appearances. Sad. I begin to articulate this with Socratic lucidity, which seems only to exacerbate the situation.

"Why don't we just have some champagne," Eric interjects. "You two can talk this over at dinner."

An admirable suggestion. I take three glasses from the cupboard, remove a bottle from the case, pop the cork, fill the glasses and propose a toast to their health.

My niece's Saab does eighty-five without a shudder on the way to dinner. With the roof down, smog blowing through my hair, I barely hear Graham who's shouting something from the passenger's seat. He's probably worried about a ticket, which for the high of this ride I'd pay twice over and tip the officer to boot. Sailing down the freeway I envision a lane of bicycles quietly recycling efficiencies once lost to the simple act of pedaling. We'll have to get the environmentalists involved which could mean government money for research and a lobbying arm to navigate any legislative interference. Test marketing in L.A. will increase the chance of celebrity endorsements and I'll probably need to do a book on the germination of the idea for release with the first wave of product. I'm thinking early 2003. The advertising tag line hits me as we glide beneath an overpass: Make Every Revolution Count.

There's a line at the restaurant and when I try to slip the maitre'd a twenty, Graham holds me back.

"Dad," he says, "you can't do that."

"Remember the time I took you to the Ritz and you told me the chicken in your sandwich was tough and I spoke to the manager and we got the meal for free? And you drew a diagram of the tree fort you wanted and it gave me an idea for storage containers."

He nods his head.

"Come on, where's your smile?"

I walk up to the maitre'd but when I hand him the twenty he gives me a funny look and I tell him he's a lousy shit for pretending he's above that sort of thing. "You want a hundred?" I ask and am about to give him an even larger piece of my mind when Graham turns me around and says, "Please don't."

"What kind of work are you doing?" I ask him.

"Dad," he says, "just settle down." His voice is so quiet, so meek.

"I asked you what kind of work you do?"

"I work at a brokerage."

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Spectacular. . . . You should buy this book, you should read it, and you should admire it. . . . [It] is the herald of a phenomenal career.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Extraordinary. . . . Frighteningly tender. . . . Displays an order as natural as a tree branch in winter—lithe and achingly austere.” —The Boston Globe

“Haslett possesses a rich assortment of literary gifts: an instinctive empathy for his characters and an ability to map their inner lives in startling detail; a knack for graceful, evocative prose; and a determination to trace the hidden arithmetic of relationships.” —The New York Times

“Fascinating. . . . Haslett is an eloquent, precise miniaturist.” —The New Yorker

“Elegant. . . . Invigorating. . . . [Haslett has an] assured, almost democratic empathy for his admirably varied characters. . . . These are graceful, mature, witty stories.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Extraordinary. . . . Frighteningly tender. . . . Displays an order as natural as a tree branch in winter—lithe and achingly austere.” —The Boston Globe

“Haslett possesses a rich assortment of literary gifts: an instinctive empathy for his characters and an ability to map their inner lives in startling detail; a knack for graceful, evocative prose; and a determination to trace the hidden arithmetic of relationships.” —The New York Times

“Fascinating. . . . Haslett is an eloquent, precise miniaturist.” —The New Yorker

“Elegant. . . . Invigorating. . . . [Haslett has an] assured, almost democratic empathy for his admirably varied characters. . . . These are graceful, mature, witty stories.” —San Francisco Chronicle

Descriere

Nine stories of surpassing maturity, poise, and intelligence that dramatize sometimes harrowing psychological situations with astonishing emotional effect.

Premii

- National Book Awards Finalist, 2002