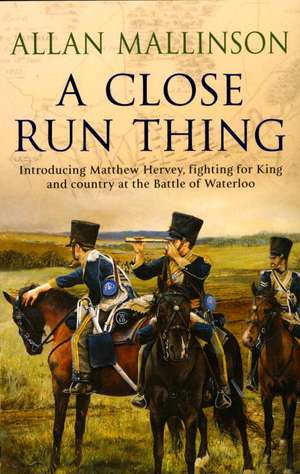

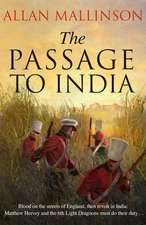

A Close Run Thing: Matthew Hervey

Autor Allan Mallinsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – mar 2000

For two decades, since the French Revolution, Britain and her allies have fought a seemingly endless war to loosen Bonaparte's stranglehold on Europe. And Englishmen such as Matthew Hervey, led by the "Iron Duke" of Wellington, have left the green pastures of home to follow the drum in His Majesty's cavalry. By 1814 Hervey, a twenty-three-year-old parson's son, has been on campaign with the 6th Light Dragoons for over five years--only to find his military career endangered by an impetuous act of gallantry....

With the French army at last defeated and Bonaparte exiled to Elba, Matthew's regiment is posted home. His return to Horningsham village reacquaints him with the vivacious beauty of Lady Henrietta Lindsay, his childhood sweetheart. But shortly he is called to duty in Ireland, where English landowners can be as pitiless as Bonaparte has been on the Continent, and where rebellion lurks in every hedgerow.

Torn by ambition and ensnared in the intrigues of Wellington's army, Matthew struggles to shape his destiny, but his efforts are about to be cast to the winds of fate. For, back amid the pounding of hooves, the flash of gunpowder, and the clash of sabers, he will find the dramatic fulfillment of his own purpose, himself a catalyst in the battle of thecentury...near the small Belgian village of Waterloo.

Written with stunning authenticity, and sweeping from battleground to country mansion, from French chateau to smoky Irish hovel, A Close Run Thing gilds history with a bold imagination in an unforgettable tale of the fortunes of war and the conflicts of the spirit.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 68.94 lei 26-32 zile | +24.51 lei 7-13 zile |

| PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC – mar 2000 | 68.94 lei 26-32 zile | +24.51 lei 7-13 zile |

| Bantam – 31 iul 2000 | 118.60 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 68.94 lei

Preț vechi: 82.37 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 103

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.19€ • 13.70$ • 11.00£

13.19€ • 13.70$ • 11.00£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 06-12 martie

Livrare express 15-21 februarie pentru 34.50 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553507133

ISBN-10: 0553507133

Pagini: 380

Ilustrații: map

Dimensiuni: 126 x 197 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Revised edition

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

Seria Matthew Hervey

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0553507133

Pagini: 380

Ilustrații: map

Dimensiuni: 126 x 197 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Revised edition

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

Seria Matthew Hervey

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Descriere

Waterloo, 1815As the war against Bonaparte rages to its bloody end upon the field of Waterloo, a young officer goes about his duty in the ranks of Wellington's army. He is Cornet Matthew Hervey of the 6th Light Dragoons - a soldier, gentleman and man or honour, who suddenly finds himself allotted a hero's role ...

Notă biografică

"Stirring...stimulating...entertaining...a richness of detail."

-USA Today

"Now at last a highly literate, deeply read cavalry officer of high rank shows one the nature of horse-borne warfare....Colonel Mallinson's a close run thing is very much to be welcomed."

-Patrick O'Brian author of the Aubrey-Maturin series

"An astonishingly impressive debut in the field of Napoleonic fiction. Convincingly drawn, perfectly paced, and expertly written, this cavalryman's tale is a joy to read."

-Anthony Beevor, author of Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege

"A rousing...tale of valiant heroism and dashing derring-do."

-Kirkus Reviews

"Mallinson expertly captures both the glory and the gore of the battlefield in this sweeping saga.... An exciting historical adventure steeped in authentic military detail."

-Booklist

-USA Today

"Now at last a highly literate, deeply read cavalry officer of high rank shows one the nature of horse-borne warfare....Colonel Mallinson's a close run thing is very much to be welcomed."

-Patrick O'Brian author of the Aubrey-Maturin series

"An astonishingly impressive debut in the field of Napoleonic fiction. Convincingly drawn, perfectly paced, and expertly written, this cavalryman's tale is a joy to read."

-Anthony Beevor, author of Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege

"A rousing...tale of valiant heroism and dashing derring-do."

-Kirkus Reviews

"Mallinson expertly captures both the glory and the gore of the battlefield in this sweeping saga.... An exciting historical adventure steeped in authentic military detail."

-Booklist

Extras

Britain had persevered in war with revolutionary France, with but one short break, since 1793. The Royal Navy, at Aboukir in 1798 and Trafalgar in 1805, had confined Bonaparte to Europe; British money had financed the allies when they were ready to come forward; and a British army in the Iberian peninsula had, from 1809, maintained a front which had drained French resources and given hope to other Europeans. By the beginning of 1814, Bonaparte could defend only France. Russian, Prussian, and Austrian armies were closing in from the east, while the British, already in the Pyrenees, stood ready to invade from the southwest.

Chapter 1: In the Heat of Battle

The Convent of St. Mary of Magdala, Toulouse, April 12, 1814

"It is a very singular thing indeed, Mr. Hervey, for a cornet to be placed in arrest upon the field of battle."

Joseph Edmonds was deploying all his considerable facility with words in order to convey the gravity of the matter at hand.

"Tell me, if you please, precisely and dispassionately, the circumstances by which this was brought about."

Cornet Hervey stood rigidly to attention before the major's desk, his left hand clasping the sword scabbard to his side, his right hand clenched with the thumb pointing downward along the double yellow stripe of his overalls. His eyes were set front, and filling the limited arc of their fixed gaze were two symbols which, while if not to his mind entirely contradictory, in their juxtaposition seemed somehow incongruous. For on the wall behind the desk was a large wooden cross with a painted figure of the crucified Christ. Next to it--perhaps even leaning against it--was the regimental guidon, a piece of red silk on a beechwood staff, its richly embroidered battle honors still resplendent despite the staining and fading. The irony, that he had been raised in a household whose world was shaped by the first symbol, and had then elected to throw himself wholeheartedly behind the second, was not lost on him even at this exigent moment. He had little imagined such a convergence, however, nor its place--a nunnery hastily and rudely requisitioned for the purposes of the military. He drew in a deep breath, his stomach feeling tighter than ever it had done when he had been awaiting combat, and began the recollection of the events which had brought him now before his commanding officer.

"Sir, yesterday forenoon I was in command of the flank picket, as you had placed me, one-quarter of a league to the west of our lines of attack upon this city. . . ."

The fateful encounter with authority had begun spectacularly. Edmonds had not expected any affair on the left flank. Not that that was why he had entrusted the picket to Hervey: he had long been of the conviction that the worst that could happen in battle usually did (and as a consequence he had never been wrong footed--at least, that is, in the field), and Hervey and his standing patrol were a trusty yet economical insurance.

Hervey had disposed his command, a half troop (by the Sixth's depleted muster scarcely two dozen men), in the dead ground to the rear of a shallow ridge running obliquely to the army's front. They were dismounted and standing easy. Posted as vidette a furlong to their front, with a view into the valley beyond the ridge, was his picket serjeant. And it was the sudden animation in that sentinel that alerted Hervey now.

"Mount!" he called, and his troopers began tightening girths before springing back into their saddles. Without an order the contact man-- the picket corporal--galloped off to Serjeant Armstrong, who had by now worked his way in cover along the ridge and farther to the flank.

Five minutes passed before the corporal returned, with intelligence that thrilled through the ranks: "Sir, there is a horse battery, six guns, approaching."

"And supports?" pressed Hervey.

"None observed, sir."

"None? No supports? That is not possible!"

"Serjeant Armstrong says there are none within the mile as he can see, sir."

Hervey could scarce believe it. But, supports or no, it would still be David and Goliath if the guns came into action before they could close with them. He hesitated not another second and took the patrol in a brisk hand gallop toward Armstrong. As they broached the ridge he held them up and edged forward with just his covering corporal to where Serjeant Armstrong was crouching in the saddle to observe over the bracken.

"They've halted, sir, just this minute," said the serjeant in his melodious Tyneside.

"Whyever do you suppose they have stopped there?" asked Hervey, peering through his telescope.

"Can't make it out at all," Armstrong replied.

They both watched the battery, halted in the valley two full furlongs away, eager to know in which direction it would next move. Armstrong thought it must turn about; Hervey was sure it would wheel left and run parallel to the ridge. Suddenly both their predictions were confounded: the French began dismounting to unlimber the guns.

Hervey's reaction was instinctive: "Draw swords! Charge!" he cried, ramming the telescope into its saddle holster and digging his spurs into his mare's flanks.

His troopers took off after him as eager as greyhounds springing a hare, but Hervey would not check his pace for the sake of dressing: he was a dozen lengths clear of the front rank by the time they were halfway to the battery, only his covering corporal within challenging distance. The French, who had seen them the instant they crested the ridge, were now frantically ramming charges down the barrels of the eight-pounders, the limbers racing back whence they had come. At a hundred yards Hervey stretched his sword arm fully to the engage and fixed on the narrow gap between the center guns. Not one had managed to load with canister by the time the troopers fell on them. In a panic two guns were fired with charges only, adding smoke to the confusion but nothing more injurious than the deafening reports. Had the gunners taken up sidearms instead, they might have inflicted some damage, but it was too late now. Hervey slashed at the battery commander as the Frenchman belatedly reached for his pistol, and the officer fell from his horse screaming, his arm all but severed at the shoulder. Hervey galloped on to the limbers, which were making heavy weather of crossing a half-sunken track (the guns were no immediate threat now and could wait--the limbers and teams would not). They showed no sign of yielding as Hervey made for the lead team, and he glanced behind to see who was with him. More than a dozen, and he could see Serjeant Armstrong still at the guns. It would do.

If only the drivers had yielded. Then they could have been made prisoner, or even set free. But no, they tried to run. In panic, or in duty to the teams? There was no time to care, even had there been time to think. Hervey pointed rather than cut at the lead driver, using his forward momentum to take the blade halfway to the hilt in the Frenchman's side. He followed through as if at sword drill in camp, effortlessly recovering the saber to set about the wheeler drivers in the same fashion. Behind him it was the same, his dragoons doing swift execution. And then they cut the traces to set loose the teams, and began driving them back toward the British lines.

Still the fight was not gone from the battery, and small-arms fire (albeit ragged) began at the guns. Hervey galloped at once to the relief of Serjeant Armstrong and his half-dozen prizetakers, but the firing was ended by the time he came up. "Start spiking, then, Serjeant Armstrong," he called, "and fire the limbers."

"Aye, sir," Armstrong replied grimly. "Jesus, but some of these bastards were a time dying!"

Hervey sheathed his saber and leaned forward in the saddle to adjust the breastplate, which had somehow twisted. In that instant a bombardier sprang from beneath one of the guns and thrust a spontoon in his thigh. Hervey's covering corporal leaped from his horse and launched so ferocious an assault that the Frenchman had no time to parry the downward swordstroke. It cleaved his skull in two, and blood bubbled like a spring for a full minute where the body lay twitching. Armstrong rushed to support Hervey in the saddle.

"Leave go," he said sharply, angry with himself for the lapse of alertness that was costing so much pain to body and pride.

Corporal Collins spluttered an apology.

"Don't be a fool, man," snapped Hervey, gripping the gash hard. "I'm not a greenhead. For heaven's sake, Serjeant Armstrong, let's get these guns spiked and then back to our post before worse arrives."

Chapter 1: In the Heat of Battle

The Convent of St. Mary of Magdala, Toulouse, April 12, 1814

"It is a very singular thing indeed, Mr. Hervey, for a cornet to be placed in arrest upon the field of battle."

Joseph Edmonds was deploying all his considerable facility with words in order to convey the gravity of the matter at hand.

"Tell me, if you please, precisely and dispassionately, the circumstances by which this was brought about."

Cornet Hervey stood rigidly to attention before the major's desk, his left hand clasping the sword scabbard to his side, his right hand clenched with the thumb pointing downward along the double yellow stripe of his overalls. His eyes were set front, and filling the limited arc of their fixed gaze were two symbols which, while if not to his mind entirely contradictory, in their juxtaposition seemed somehow incongruous. For on the wall behind the desk was a large wooden cross with a painted figure of the crucified Christ. Next to it--perhaps even leaning against it--was the regimental guidon, a piece of red silk on a beechwood staff, its richly embroidered battle honors still resplendent despite the staining and fading. The irony, that he had been raised in a household whose world was shaped by the first symbol, and had then elected to throw himself wholeheartedly behind the second, was not lost on him even at this exigent moment. He had little imagined such a convergence, however, nor its place--a nunnery hastily and rudely requisitioned for the purposes of the military. He drew in a deep breath, his stomach feeling tighter than ever it had done when he had been awaiting combat, and began the recollection of the events which had brought him now before his commanding officer.

"Sir, yesterday forenoon I was in command of the flank picket, as you had placed me, one-quarter of a league to the west of our lines of attack upon this city. . . ."

The fateful encounter with authority had begun spectacularly. Edmonds had not expected any affair on the left flank. Not that that was why he had entrusted the picket to Hervey: he had long been of the conviction that the worst that could happen in battle usually did (and as a consequence he had never been wrong footed--at least, that is, in the field), and Hervey and his standing patrol were a trusty yet economical insurance.

Hervey had disposed his command, a half troop (by the Sixth's depleted muster scarcely two dozen men), in the dead ground to the rear of a shallow ridge running obliquely to the army's front. They were dismounted and standing easy. Posted as vidette a furlong to their front, with a view into the valley beyond the ridge, was his picket serjeant. And it was the sudden animation in that sentinel that alerted Hervey now.

"Mount!" he called, and his troopers began tightening girths before springing back into their saddles. Without an order the contact man-- the picket corporal--galloped off to Serjeant Armstrong, who had by now worked his way in cover along the ridge and farther to the flank.

Five minutes passed before the corporal returned, with intelligence that thrilled through the ranks: "Sir, there is a horse battery, six guns, approaching."

"And supports?" pressed Hervey.

"None observed, sir."

"None? No supports? That is not possible!"

"Serjeant Armstrong says there are none within the mile as he can see, sir."

Hervey could scarce believe it. But, supports or no, it would still be David and Goliath if the guns came into action before they could close with them. He hesitated not another second and took the patrol in a brisk hand gallop toward Armstrong. As they broached the ridge he held them up and edged forward with just his covering corporal to where Serjeant Armstrong was crouching in the saddle to observe over the bracken.

"They've halted, sir, just this minute," said the serjeant in his melodious Tyneside.

"Whyever do you suppose they have stopped there?" asked Hervey, peering through his telescope.

"Can't make it out at all," Armstrong replied.

They both watched the battery, halted in the valley two full furlongs away, eager to know in which direction it would next move. Armstrong thought it must turn about; Hervey was sure it would wheel left and run parallel to the ridge. Suddenly both their predictions were confounded: the French began dismounting to unlimber the guns.

Hervey's reaction was instinctive: "Draw swords! Charge!" he cried, ramming the telescope into its saddle holster and digging his spurs into his mare's flanks.

His troopers took off after him as eager as greyhounds springing a hare, but Hervey would not check his pace for the sake of dressing: he was a dozen lengths clear of the front rank by the time they were halfway to the battery, only his covering corporal within challenging distance. The French, who had seen them the instant they crested the ridge, were now frantically ramming charges down the barrels of the eight-pounders, the limbers racing back whence they had come. At a hundred yards Hervey stretched his sword arm fully to the engage and fixed on the narrow gap between the center guns. Not one had managed to load with canister by the time the troopers fell on them. In a panic two guns were fired with charges only, adding smoke to the confusion but nothing more injurious than the deafening reports. Had the gunners taken up sidearms instead, they might have inflicted some damage, but it was too late now. Hervey slashed at the battery commander as the Frenchman belatedly reached for his pistol, and the officer fell from his horse screaming, his arm all but severed at the shoulder. Hervey galloped on to the limbers, which were making heavy weather of crossing a half-sunken track (the guns were no immediate threat now and could wait--the limbers and teams would not). They showed no sign of yielding as Hervey made for the lead team, and he glanced behind to see who was with him. More than a dozen, and he could see Serjeant Armstrong still at the guns. It would do.

If only the drivers had yielded. Then they could have been made prisoner, or even set free. But no, they tried to run. In panic, or in duty to the teams? There was no time to care, even had there been time to think. Hervey pointed rather than cut at the lead driver, using his forward momentum to take the blade halfway to the hilt in the Frenchman's side. He followed through as if at sword drill in camp, effortlessly recovering the saber to set about the wheeler drivers in the same fashion. Behind him it was the same, his dragoons doing swift execution. And then they cut the traces to set loose the teams, and began driving them back toward the British lines.

Still the fight was not gone from the battery, and small-arms fire (albeit ragged) began at the guns. Hervey galloped at once to the relief of Serjeant Armstrong and his half-dozen prizetakers, but the firing was ended by the time he came up. "Start spiking, then, Serjeant Armstrong," he called, "and fire the limbers."

"Aye, sir," Armstrong replied grimly. "Jesus, but some of these bastards were a time dying!"

Hervey sheathed his saber and leaned forward in the saddle to adjust the breastplate, which had somehow twisted. In that instant a bombardier sprang from beneath one of the guns and thrust a spontoon in his thigh. Hervey's covering corporal leaped from his horse and launched so ferocious an assault that the Frenchman had no time to parry the downward swordstroke. It cleaved his skull in two, and blood bubbled like a spring for a full minute where the body lay twitching. Armstrong rushed to support Hervey in the saddle.

"Leave go," he said sharply, angry with himself for the lapse of alertness that was costing so much pain to body and pride.

Corporal Collins spluttered an apology.

"Don't be a fool, man," snapped Hervey, gripping the gash hard. "I'm not a greenhead. For heaven's sake, Serjeant Armstrong, let's get these guns spiked and then back to our post before worse arrives."

Recenzii

"Of recent years many eminent hands have undertaken to lead the reader deep into the Royal Navy of Nelson's time, describing the life of the service, the men who sailed those 'far-distant, storm-beaten ships, upon which the Grand Army never looked' but which 'stood between it and the dominion of the world.'

"Hitherto nobody that I know of has done anything like the same for the army, which did after all have a not inconsiderable share in winning the war; but now at last a highly literate, deeply read cavalry officer of high rank shows one the nature of horse-borne warfare in those times; and Colonel Mallinson's A Close Run Thing is very much to be welcomed."

--Patrick O'Brian, author of the Aubrey-Maturin series

"Mallinson's A Close Run Thing is an astonishingly impressive debut in the field of Napoleonic fiction. Convincingly drawn, perfectly paced and expertly written, this cavalryman's tale is a joy to read. I hope it will be the first of many."

--Antony Beevor, author of Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege

From the Hardcover edition.

"Hitherto nobody that I know of has done anything like the same for the army, which did after all have a not inconsiderable share in winning the war; but now at last a highly literate, deeply read cavalry officer of high rank shows one the nature of horse-borne warfare in those times; and Colonel Mallinson's A Close Run Thing is very much to be welcomed."

--Patrick O'Brian, author of the Aubrey-Maturin series

"Mallinson's A Close Run Thing is an astonishingly impressive debut in the field of Napoleonic fiction. Convincingly drawn, perfectly paced and expertly written, this cavalryman's tale is a joy to read. I hope it will be the first of many."

--Antony Beevor, author of Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege

From the Hardcover edition.