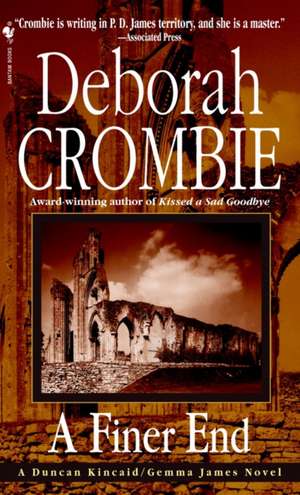

A Finer End: Duncan Kincaid/Gemma James Novel

Autor Deborah Crombieen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2002

A FINER END

When Duncan Kincaid’s cousin Jack calls from Glastonbury to ask for his help on a rather unusual matter, Duncan welcomes the chance to spend a relaxing weekend outside of London with Gemma--but relaxation isn’t on the agenda. Glastonbury is revered as the site of an ancient abbey, the mythical burial place of King Arthur and Guinevere, and a source of strong druid power. Jack has no more than a passing interest in its history--until he comes across an extraordinary chronicle almost a thousand years old. The record reveals something terrible and bloody shattered the abbey’s peace long ago--knowledge that will spark violence that reaches into the present. Soon it is up to Duncan and Gemma to find the truth the local police cannot see. But no one envisions the peril that lies ahead--or that there is more at stake than they ever dreamed possible.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 48.89 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Bantam – 30 apr 2002 | 48.89 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| MacMillan – 11 apr 2013 | 97.16 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 48.89 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 73

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.35€ • 9.79$ • 7.74£

9.35€ • 9.79$ • 7.74£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553579277

ISBN-10: 0553579274

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 108 x 176 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Ediția:Bantam Pbk.

Editura: Bantam

Seria Duncan Kincaid/Gemma James Novel

ISBN-10: 0553579274

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 108 x 176 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Ediția:Bantam Pbk.

Editura: Bantam

Seria Duncan Kincaid/Gemma James Novel

Notă biografică

Deborah Crombie's Duncan Kincaid/Gemma James novels have been nominated for the Agatha, Macavity, and Edgar Awards. She lives with her family in a small North Texas town, where she is at work on the next book of the series, And Justice There Is None.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

Imagination is a great gift, a Divine power of the mind, and may be trained and educated to create and to receive only that which is true.

-Frederick Bligh Bond, from The Gate of Remembrance

The shadows crept into Jack Montfort’s small office, filling the corners with a comfortable dimness. He’d come to look forward to his time alone at the day’s end, he told himself he got more done without phones ringing and the occasional client calling in, but perhaps, he thought wryly, it was merely that he had little enough reason to go home.

Standing at his window, he gazed down at the pedestrians hurrying along either side of Magdalene Street, and wondered idly where they were all scurrying off to so urgently on a Wednesday evening. Across the street the Abbey gates had shut at five, and as he watched, the guard let the last few stragglers out from the grounds. The March day had been bright with a biting wind, and Jack imagined that anyone who’d been enticed by the sun into wandering around the Abbey’s fishpond would be chilled to the bone. Now the remaining buttresses of the great church would be silhouetted against the clear rose of the eastern sky, a fitting reward for those who had braved the cold.

He’d counted himself lucky to get the two-room office suite with its first-floor view over the Market Square and the Abbey gate. It was a prime spot, and the restrictions involved in renovating a listed building hadn’t daunted him. His years in London had given him experience enough in working round constraints, and he’d managed to up- date the rooms to his satisfaction without going over his budget. He’d hired a secretary to preside over his new reception area, and begun the slow task of building an architectural practice.

And if a small voice still occasionally whispered, Why bother? he did his best to ignore it and get on with things the best way he knew how, although he’d learned in the last few years that plans were ephemeral blueprints. Even as a child, he’d had his life mapped out: university with first-class honors, a successful career as an architect . . . wife . . . family. What he hadn’t bargained for was life’s refusal to cooperate. Now they were all gone, his mum, his dad . . . Emily. At forty, he was back in Glastonbury. It was a move he’d have found inconceivable twenty years earlier, but here he was, alone in his parents’ old house on Ashwell Lane, besieged by memories.

Rolling up his shirtsleeves, he sat at his desk and positioned a blank sheet of paper in the pool of light cast by his Anglepoise lamp. Sitting round feeling sorry for himself wasn’t going to do a bit of good, and he had a client expecting a bid tomorrow morning on a residential refurbishment. And besides, if he finished his work quickly, he could look forward to the possibility of dinner with Winnie.

The thought of the unexpected entry of Winifred Catesby into his life made him smile. Besieged by arranged dates as soon as his mother’s well-meaning friends decided he’d endured a suitable period of mourning, he’d found the effort of making conversation with needy divorcees more depressing than time spent alone. He’d begged off so often that the do-gooders had declared him hopeless and finally left him alone.

Relieved of unwelcome obligations, he’d found himself driving the five miles to Wells for the solace of the Evensong service in the cathedral more and more frequently. The proximity of the cathedral choir was one of the things that had drawn him back to Glastonbury, he’d sung at Wells as a student in the cathedral school, and the experience had given him a lifelong passion for church music.

And then one evening a month ago, as he found his usual place in the ornately carved stall in the cathedral choir, she had slipped in beside him, a pleasantly ordinary-looking woman in her thirties, with light brown hair escaping from beneath a floppy velvet hat, and a slightly upturned nose. He had not noticed her particularly, just nodded in the vague way one did as she took her seat. The service began, and in that moment when the first high reach of the treble voices sent a shiver down his spine, she had met his eyes and smiled.

Afterwards, they had chatted easily, naturally, and as they walked out of the cathedral together, deep in discussion of the merits of various choirs, he’d impulsively invited her for a drink at the pub down the street. It wasn’t until he’d helped her out of her coat that he’d seen the clerical collar.

Emily, always chiding him for his conservatism, would have been delighted by his consternation. And Emily, he felt sure, would have liked Winnie. He extended a finger to touch the photograph on his desktop and Emily gazed back at him, her dark eyes alight with humor and intelligence.

His throat tightened. Would the ache of his loss always lie so near the surface? Or would it one day fade to a gentle awareness, as familiar and unremarkable as a burr beneath the skin? But did he really want that? Would he be less himself without Emily’s constant presence in his mind?

He grinned in spite of himself. Emily would tell him to stop being maudlin and get on with the task at hand. With a sigh, he looked down at his paper, then blinked in surprise.

He held a pen in his right hand, although he didn’t remember picking it up. And the page, which had been blank a moment ago, was covered in an unfamiliar script. Frowning, he checked for another sheet beneath the paper. But there was only the one page, and as he examined it more closely, he saw that the small, precise script seemed to be in Latin. As he recalled enough of his schoolboy vocabulary to make a rough translation, his frown deepened.

Know ye what we . . . Jack puzzled a moment before deciding on builded, then there was something he couldn’t make out, then the script continued, . . . in Glaston. Meaning Glastonbury? It was fair as, . . . any earthly thing, and had I not loved it overmuch my spirit would not cling to dreams of all now vanished.

Ye love full well what we have loved. The time . . . Here Jack was forced to resort to the dog-eared Latin dictionary in his bookcase, and after concluding that the phrase had something to do with sleeping or sleepers, went impatiently on . . . to wake, for Glaston to rise against the darkness. We have . . . something . . . long for you . . . it is in your hands. . . .

After this sentence there was a trailing squiggle beginning with an E, which might have been a signature, perhaps “Edmund.”

Was this some sort of a joke, invisible ink that appeared when exposed to the light? But his secretary didn’t strike him as a prankster, and he’d taken the paper from a ream he’d just unwrapped himself. That left only the explanation that he had penned these words, alien in both script and language. But that was absurd. How could he have done so, unaware?

The walls of Jack’s office leaned in on him, and the silence, usually so soothing, seemed alive with tension. He felt breathless, as if all the air in the small room had been used up.

Who were “they,” who had built in Glastonbury and who wrote in Latin? The monks of the Abbey, he supposed, a logical answer. And “he,” who had “loved it overmuch,” whose spirit “still clung to dreams long vanished”? The ghost of a monk? Worse by the minute.

What did “rise against the darkness” mean? And what had any of it to do with him? The whole thing was completely daft; he refused to consider it any further.

Crumpling the page, Jack swiveled his chair round, hand lifted to toss it in the bin, then stopped and returned the paper to his desk, smoothing the creases out with his palm.

Frederick Bligh Bond. The name sprang into his mind, dredged from the recesses of his childhood. The architect who, just before the First World War, had undertaken the first excavations at Glastonbury Abbey, then revealed that he had been directed by messages from the Abbey monks. Had Bond received communications like this? But Bond had been loony. Cracked!

Ripping the sheet of paper in half, Jack dropped the pieces in the bin, slipped into his jacket, and, sketch pad in hand, took the stairs down to the street two at a time.

He stepped out into Benedict Street, fumbling with unsteady fingers to lock his office door. Across the Market Square, the leaded windows of the George & Pilgrims beckoned. A drink, he thought with a shiver, was just what he needed. He’d work on his proposal, and the crowded bar of the old inn would surely make an antidote to whatever it was that had just happened to him.

Tugging his collar up against the wind, he sidestepped a group of adolescent skateboarders who found the smooth pavement round the Market Cross a perfect arena. A particularly fierce gust sent a sheet of paper spiraling past his cheek. He grabbed at it in instinctive self-defense, glancing absently at what he held in his fingers. Pink. A flyer, from the Avalon Society. Glastonbury Assembly Rooms, Saturday, 7:30 to 9:30. An introduction to crystal energy and its healing powers, showing how the chakras and crystals correspond. Make elixirs and learn how to energize your environment.

“Oh, bloody perfect,” he muttered, crumpling the paper and tossing it back to the wind. That was the worst sort of nonsense, just the type of thing that drew the most extreme New Age followers to Glastonbury. Ley lines . . . crop circles . . . Druid magic on Glastonbury Tor, the ancient, conical hill that rose above the town like a beacon . . .

Although Jack, like generations of his family, had grown up in the Tor’s shadow, he’d never given any credence to all the mystical rubbish associated with it, nor to the myths that described Glastonbury as some sort of cosmic mother lode.

So why on earth had he just scribbled what seemed to be a garbled message from some long-dead monk? Was he losing his mind? A delayed reaction to grief, perhaps? He had read about post-traumatic stress syndrome, could that explain what had happened to him? But somehow he sensed it was more than that. For an instant, he saw again the small, precise script, a thing of beauty in itself, and felt a tug of familiarity in the cadence of the language.

He resumed his walk to the pub, then a thought stopped him midstride. What if, what if it were even remotely possible that he had made contact with the dead? Did that mean . . . could it mean he was capable of instigating contact at will? Emily,

No. He couldn’t even allow the idea of such a thing. That way lay madness.

A skateboarder whooshed past him, wheels clacking. “You taking root, mister?” the boy called out. Jack lurched unsteadily on, across the bottom of the High Street towards the George & Pilgrims. As he reached the pub, the heavy door swung open and a knot of revelers pushed past him. An escaping hint of laughter and smoke offered safe haven before the wind snatched sound and scent away; and then, he could have sworn, he heard, faintly, the sound of bells.

The cats slept in the farmyard, taking advantage of the midday warmth of the pale spring sun. Each had its own spot, a flower pot, the sagging step at the kitchen door, the bonnet of the old white van that Garnet Todd used to deliver her tiles, and only the occasional twitch of a feline ear or tail betrayed their awareness of the rustle of mice in the straw.

Garnet stood in the doorway of her workshop, wiping her hands on the leather apron she wore as a protection against the heat of the kiln. She had almost completed her latest commission, the restoration of the tile flooring in a twelfth-century church near the edge of Salisbury Plain. The manufacture of the tiles was painstaking work. The pattern suggested by the few intact bits of floor must be matched, using only the materials and techniques available to the original artisans. Then came the installation, a delicate process requiring hours spent on hands and knees, breathing the dank and musty atmosphere of the ancient church.

But Garnet never minded that. She was most comfortable with old things. Even her work as a midwife, although it had honored the Goddess, had not given her enough visceral connection with the past.

Her farm, a ramshackle place she’d bought more than twenty-five years ago, was proof of how little use she had for the present. The house stood high on the western flank of the Tor, its pitted stone facade in the path of a wind that had scoured down from the hilltop for years beyond memory. The sheep that grazed the grassy slope were her nearest neighbors, and for the most part she preferred their company.

At first she’d meant to put in the electricity and running water, but the years had passed and she’d got used to doing without. Lantern light brought ochre warmth and comforting shadows, and why should she drink the chemically poisoned water the town pumped out of its tanks when the spring on her property bubbled right up from the heart of the sacred hill? Enough had been done in this town to dishonor the old and holy things without her adding to the damage.

A cloud shadow raced down the hillside and for a moment the yard darkened. Garnet shivered. Dion, the old calico cat who ruled the rest of the brood with regal disdain, uncurled herself from the flower pot and came to rub against Garnet’s ankles. “You sense it, too, don’t you, old girl?” Garnet said softly, bending to stroke her. “Something’s brewing.”

Once, long ago, she had caught that scent in the air, once before she had felt that prickle of foreboding, and the memory of the outcome filled her with dread.

Glastonbury had always been a place of power, a pivot point in the ancient battle between the light and the dark. If that delicate balance were disturbed, Garnet knew, not even the Goddess could foresee the consequences.

**********************

Glastonbury did strange things to people, as Nick Carlisle had reason to know. He’d come here for the Festival, part of his plan to take a few months off, see a bit of the world, after leaving Durham with a first in philosophy and theology. On a mild evening in late June he had rounded a bend in the Shepton Mallet Road and seen the great conical hump of the Tor rising above the plain, St. Michael’s Tower on its summit standing squarely against the bloodred western sky.

That had been more than a year ago, and he was still here, working in a New Age bookshop across from the Abbey for little more than minimum wage, living in a caravan in a farmer’s field in Compton Dundon, and trying to forget all that he had left behind.

He often came to the George & Pilgrims for a pint after work. A fine thing, when a pub did duty as his home away from home, but then his caravan didn’t count for much, a place to put the faded jeans, T-shirts, and sweatshirts that made up his meager wardrobe, along with the books he’d brought with him from Durham. The small fridge smelled of sour milk, and the two-ring gas cooker was as temperamental as his mother.

The thought of his mum made him grimace. Elizabeth Carlisle had raised her son alone from his infancy, and in the process had managed to make quite a successful career for herself penning North Country Aga sagas. She had managed her son’s life as efficiently as she did her characters’, and had then pronounced herself affronted by his resentment.

Furious at his mother’s usurping of his responsibilities, he had convinced himself that he would be able to sort out his life as soon as he escaped her orbit. But freedom had not turned out to be the panacea he’d expected: he had no more idea what he wanted to do with his life than he’d had a year ago. He only knew that something held him in Glastonbury, and yet he burned with a restless and unfulfilled energy.

From his corner table, he surveyed the pub’s clientele as he sipped his beer. There was an unusual yuppie element this evening, young men sporting designer suits, accompanied by polished girls in skimpy clothes. Nick could almost feel the rumble of displeasure among the regulars, clustered at the bar in instinctive solidarity.

One of the girls caught his eye and smiled. Nick looked away. Predators in makeup and spandex, girls meant nothing but trouble. First they liked his looks, then, once they found out who his mother was, they saw him as a ready-made meal ticket. But he’d learned his lesson well, and would not let himself fall into that trap again.

Turning his back on the group, he found his attention held by the man sitting alone at the bar’s end. The man was notable not only for his large size and fair hair, but also because his face was familiar. Nick had seen him often in Magdalene Street, he must work near the bookshop, and once or twice they had exchanged a friendly nod. Tonight he sat hunched over his drink, his usually amiable countenance set in a scowl.

Intrigued, Nick saw that he seemed to be writing or sketching on a pad, and that every few moments he raised visibly trembling fingers to brush a lock of hair from his forehead.

When Nick made his way to the bar for a refill, the blond man was staring fixedly at his beer glass, his pen poised over the paper. Nick glanced at the pad. It held neat architectural drawings and figures, and, scrawled haphazardly across the largest sketch, a few lines in what looked to be Latin. It is for my sins Glaston suffered . . . he translated silently.

“You’re a classics scholar?” Nick said aloud, surprised.

“What?” The man blinked owlishly at him. For a moment Nick wondered if he were drunk, but he’d been nursing the same drink since Nick had noticed him.

Nick tapped the sketch pad. “This. I don’t often see anyone writing in Latin.”

Glancing down, the man paled. “Oh, Christ. Not again.”

“Sorry?”

“No, no. It’s quite all right.” The man shook his head and seemed to make a great effort to focus on Nick. “Jack Montfort. I’ve seen you, haven’t I? You work in the bookshop.”

“Nick Carlisle.”

“My office is just upstairs from your shop.” Montfort gestured at Nick’s empty glass. “What are you drinking?”

Montfort bought two more pints, then turned back to Nick. Now he seemed eager to talk. “Working at the bookshop, I suppose you read a good bit?”

“Like a kid in a sweetshop. The manager’s a good egg, turns a blind eye. And I try not to dog-ear the merchandise.”

“I have to admit I’ve never been in the place. Interesting stuff, is it?”

“Some of it’s absolute crap,” Nick replied with a grin. “UFOs. Crop circles, everyone knows that’s a hoax. But some of it . . . well, you have to wonder. . . . Odd things do seem to happen in Glastonbury.”

“You could say that,” Montfort muttered into his beer, his scowl returning. Then he seemed to try to shake off his preoccupation. “You’re not from around here, are you? Do I detect a hint of Yorkshire?”

“It’s Northumberland, actually. I came for the Festival last year”, Nick shrugged, “and I’m still here.”

“Ah, the rock festival at Pilton. Somehow I never managed to get there. I suppose I missed something memorable.”

“Mud.” Nick grinned. “Oceans of it. And slogging about in some farmer’s field, being bitten by midges, drinking bad beer, and queuing for hours to use the toilets. Still . . .”

“There was something,” Montfort prompted.

“Yeah. I’d like to have seen it in its heyday, the early seventies, you know? Glastonbury Fayre, they called it. That must have been awesome. And even that didn’t compare to the original Glastonbury Festival, in terms of quality, not quantity.”

“Original festival?” Montfort repeated blankly.

“Started in 1914 by the composer Rutland Boughton,” Nick answered. “Boughton was extremely talented, his opera The Immortal Hour still holds the record for the longest-running operatic production. All sorts of luminaries were involved in the Festival: Shaw, Edward Elgar, Vaughan Williams, D. H. Lawrence. And Glastonbury had its own contributors to the cultural revival, people like Frederick Bligh Bond and Alice Buckton. . . . And then there was the business of Bond’s friend Dr. John Goodchild and the finding of the ‘Grail’ in Bride’s Well. That caused a few ripples. . . .” Aware that he was babbling, Nick paused and drank the foam off his pint.

Looking up, he saw that Montfort was staring at him. Nick flushed. “Sorry. I get a bit carried away some, “

“You know about Bligh Bond?”

The intensity in Montfort’s voice took Nick by surprise. “Well, it’s a fascinating story, isn’t it? Bond’s knowledge was prodigious, his excavations at the Abbey were proof of that. But I suppose one can’t blame the Church for being a bit uncomfortable with the idea that Bond had received his digging instructions from monks dead five centuries or more.”

“Uncomfortable?” Montfort snorted. “They fired him. He never worked successfully as an architect again and, if I remember rightly, died in poverty. If the man had had an ounce of bloody sense, he’d have kept his mouth shut.”

“He felt he had to share it, though, didn’t he? I’d say Bond was honest to a fault. And I don’t think he ever actually claimed he’d made contact with spirits. He thought he might have merely accessed some part of his own subconscious.”

“Do you believe it’s possible, whatever the source?”

“Bond’s not the only case. There have been well- documented instances where people have known things about the past that couldn’t be accounted for otherwise.” Glancing at the paper Montfort had partially covered with his hand, Nick felt a fizz of excitement. “But you’re not talking hypothetically, are you?”

“This is”, Montfort shook his head, “daft. Too daft to tell anyone. But the coincidence, meeting you here . . . I, “ He looked around, as if suddenly aware of the proximity of other customers, and lowered his voice.

“I was sitting at my desk tonight, and I wrote . . . something. In Latin I haven’t used since I was at school, and I had no memory of writing it. I tore the damned thing up. . . . Then this. . . .” He ran his fingertips across the scrawl on the sketch pad.

“Bugger,” Nick breathed, awed. “I’d swap my mum to have that happen to me.”

“But why me? I didn’t ask for this,” Montfort retorted fiercely. “I’m an architect, but my knowledge of the Abbey is no more than you’d expect from anyone who grew up here. I’m not particularly religious. I’ve never had any interest in spiritualism, or otherworldly things of any sort, for that matter.”

Nick pondered this for a moment. “I doubt these things are random. Maybe you have some connection to the Abbey that you’re not consciously aware of.”

“That’s a big help,” Montfort said, but there was a gleam of humor in his bright blue eyes. “So how do I find out what it is, and why this is happening to me?”

“Maybe I could help. You know it wasn’t Bond who did the actual writing, but his friend, John Bartlett. Bond guided him by asking questions.”

“You want to play Bond to my Bartlett, then?”

“You said you came from Glastonbury. That seems as good a place to start as any.”

“My father’s family’s been in Glastonbury and round about for eons, I should think. He was a solicitor. A large, serious man, very sure of where he stood in the world.” Montfort took a sip of his beer and his voice softened as he continued. “Now, my mother, she was a different sort altogether. She loved stories, loved to play make-believe with us when we were children.”

“Us?”

“My cousins and I. Duncan and Juliet. My aunt and uncle had a penchant for Shakespeare. We always visited them in Cheshire on our holidays. It was a different world. The canals, and then the hills of Wales rising in the distance. . . .”

Once more he fell silent, his eyes half closed. Nick was about to prompt him again, when, without warning, Montfort grasped the pen. His hand began to move steadily across the paper.

Nick translated the Latin as the words began to form. Deo juvante . . . With God’s help . . . you shall make it right. . . . Did that, he wondered, apply to him as well? Could he somehow set right what he had done?

In that instant, Nick knew why he had come to Glastonbury, and he knew why he had stayed.

Faith Wills rested her forehead against the cool plastic of the toilet seat, panting, her eyes swimming with the tears brought on by retching. She had nothing left to throw up but the lining of her stomach, yet somehow she was going to have to pull herself together, go out, and face the smell of her mother’s breakfast.

It was a bacon-and-egg morning, her mum believed all children should go off to school well fortified for the day. They alternated cooked eggs, or porridge, or brown toast and marmite; and on this Thursday morning in March, Faith had struck the worst possible option.

A whiff of bacon crept into the bathroom. Her stomach heaved treacherously just as her younger brother, Jonathan, pounded on the door. “You think you’re effing Madonna in there or something? Hurry bloody up, Faith!”

Without raising her head, Faith said, “Shut up,” but it came out a whisper.

Then her mother’s voice, “Jonathan, you watch your language,” and the crisp rap of knuckles on the door. “Faith, whatever’s the matter with you? You’re going to be late, and make Jon and Meredith late as well.”

“Coming.” Unsteadily, Faith pushed herself up, flushed the toilet, then blew her nose on a piece of toilet tissue. Easing the door open, she found her mum waiting, hands on hips, and beyond her, Jon, and her sister, Meredith, all three faces set in varying degrees of irritation. “What is this, a committee?” she asked, trying for a bit of attitude.

Her mother ignored her, taking her chin in firm fingers and turning her face towards the wan light filtering in from the sitting room. “You’re white as a sheet,” she pronounced. “Are you ill?”

Faith swallowed convulsively against the kitchen smells, then managed to croak, “I’m okay. Just exam nerves.”

Her dad emerged from the bedroom, tying his tie. “How many times have I told you not to leave studying until the last minute? And you know how important your GCSEs, “

“Just let me get my books, okay?”

“Don’t take that tone with me, young lady.” Her dad jerked tight the knot of his tie and reached for her. His fingertips dug into the flesh of her bare arm.

“Sorry,” Faith mumbled, not meeting his eyes. Tugging free, she escaped to the room she shared with her sister and, once inside, leaned against the door, praying for a moment’s peace before Meredith came back. It was a child’s room, she thought, seeing it suddenly anew. The walls were covered with posters of rock stars, the twin beds with bedraggled stuffed animals. Her hockey uniform spilled from her satchel; the sheets of music for that afternoon’s choir practice lay scattered on the floor. All things that had mattered so much to her, all utterly meaningless now.

She wouldn’t be fine, she realized, closing her eyes against the tide of despair that swept over her. Nothing would ever be fine again.

And she couldn’t tell her parents. In her mother’s perfect world, seventeen-year-olds didn’t start the day with their heads in the toilet, and her dad, well, she couldn’t think about that.

She had promised never to tell, and that was all that mattered.

Faith hugged herself, pressing her arms against the new and painful swelling of her breasts. Never, never, never. The word became a litany as she swayed gently.

Ever.

Imagination is a great gift, a Divine power of the mind, and may be trained and educated to create and to receive only that which is true.

-Frederick Bligh Bond, from The Gate of Remembrance

The shadows crept into Jack Montfort’s small office, filling the corners with a comfortable dimness. He’d come to look forward to his time alone at the day’s end, he told himself he got more done without phones ringing and the occasional client calling in, but perhaps, he thought wryly, it was merely that he had little enough reason to go home.

Standing at his window, he gazed down at the pedestrians hurrying along either side of Magdalene Street, and wondered idly where they were all scurrying off to so urgently on a Wednesday evening. Across the street the Abbey gates had shut at five, and as he watched, the guard let the last few stragglers out from the grounds. The March day had been bright with a biting wind, and Jack imagined that anyone who’d been enticed by the sun into wandering around the Abbey’s fishpond would be chilled to the bone. Now the remaining buttresses of the great church would be silhouetted against the clear rose of the eastern sky, a fitting reward for those who had braved the cold.

He’d counted himself lucky to get the two-room office suite with its first-floor view over the Market Square and the Abbey gate. It was a prime spot, and the restrictions involved in renovating a listed building hadn’t daunted him. His years in London had given him experience enough in working round constraints, and he’d managed to up- date the rooms to his satisfaction without going over his budget. He’d hired a secretary to preside over his new reception area, and begun the slow task of building an architectural practice.

And if a small voice still occasionally whispered, Why bother? he did his best to ignore it and get on with things the best way he knew how, although he’d learned in the last few years that plans were ephemeral blueprints. Even as a child, he’d had his life mapped out: university with first-class honors, a successful career as an architect . . . wife . . . family. What he hadn’t bargained for was life’s refusal to cooperate. Now they were all gone, his mum, his dad . . . Emily. At forty, he was back in Glastonbury. It was a move he’d have found inconceivable twenty years earlier, but here he was, alone in his parents’ old house on Ashwell Lane, besieged by memories.

Rolling up his shirtsleeves, he sat at his desk and positioned a blank sheet of paper in the pool of light cast by his Anglepoise lamp. Sitting round feeling sorry for himself wasn’t going to do a bit of good, and he had a client expecting a bid tomorrow morning on a residential refurbishment. And besides, if he finished his work quickly, he could look forward to the possibility of dinner with Winnie.

The thought of the unexpected entry of Winifred Catesby into his life made him smile. Besieged by arranged dates as soon as his mother’s well-meaning friends decided he’d endured a suitable period of mourning, he’d found the effort of making conversation with needy divorcees more depressing than time spent alone. He’d begged off so often that the do-gooders had declared him hopeless and finally left him alone.

Relieved of unwelcome obligations, he’d found himself driving the five miles to Wells for the solace of the Evensong service in the cathedral more and more frequently. The proximity of the cathedral choir was one of the things that had drawn him back to Glastonbury, he’d sung at Wells as a student in the cathedral school, and the experience had given him a lifelong passion for church music.

And then one evening a month ago, as he found his usual place in the ornately carved stall in the cathedral choir, she had slipped in beside him, a pleasantly ordinary-looking woman in her thirties, with light brown hair escaping from beneath a floppy velvet hat, and a slightly upturned nose. He had not noticed her particularly, just nodded in the vague way one did as she took her seat. The service began, and in that moment when the first high reach of the treble voices sent a shiver down his spine, she had met his eyes and smiled.

Afterwards, they had chatted easily, naturally, and as they walked out of the cathedral together, deep in discussion of the merits of various choirs, he’d impulsively invited her for a drink at the pub down the street. It wasn’t until he’d helped her out of her coat that he’d seen the clerical collar.

Emily, always chiding him for his conservatism, would have been delighted by his consternation. And Emily, he felt sure, would have liked Winnie. He extended a finger to touch the photograph on his desktop and Emily gazed back at him, her dark eyes alight with humor and intelligence.

His throat tightened. Would the ache of his loss always lie so near the surface? Or would it one day fade to a gentle awareness, as familiar and unremarkable as a burr beneath the skin? But did he really want that? Would he be less himself without Emily’s constant presence in his mind?

He grinned in spite of himself. Emily would tell him to stop being maudlin and get on with the task at hand. With a sigh, he looked down at his paper, then blinked in surprise.

He held a pen in his right hand, although he didn’t remember picking it up. And the page, which had been blank a moment ago, was covered in an unfamiliar script. Frowning, he checked for another sheet beneath the paper. But there was only the one page, and as he examined it more closely, he saw that the small, precise script seemed to be in Latin. As he recalled enough of his schoolboy vocabulary to make a rough translation, his frown deepened.

Know ye what we . . . Jack puzzled a moment before deciding on builded, then there was something he couldn’t make out, then the script continued, . . . in Glaston. Meaning Glastonbury? It was fair as, . . . any earthly thing, and had I not loved it overmuch my spirit would not cling to dreams of all now vanished.

Ye love full well what we have loved. The time . . . Here Jack was forced to resort to the dog-eared Latin dictionary in his bookcase, and after concluding that the phrase had something to do with sleeping or sleepers, went impatiently on . . . to wake, for Glaston to rise against the darkness. We have . . . something . . . long for you . . . it is in your hands. . . .

After this sentence there was a trailing squiggle beginning with an E, which might have been a signature, perhaps “Edmund.”

Was this some sort of a joke, invisible ink that appeared when exposed to the light? But his secretary didn’t strike him as a prankster, and he’d taken the paper from a ream he’d just unwrapped himself. That left only the explanation that he had penned these words, alien in both script and language. But that was absurd. How could he have done so, unaware?

The walls of Jack’s office leaned in on him, and the silence, usually so soothing, seemed alive with tension. He felt breathless, as if all the air in the small room had been used up.

Who were “they,” who had built in Glastonbury and who wrote in Latin? The monks of the Abbey, he supposed, a logical answer. And “he,” who had “loved it overmuch,” whose spirit “still clung to dreams long vanished”? The ghost of a monk? Worse by the minute.

What did “rise against the darkness” mean? And what had any of it to do with him? The whole thing was completely daft; he refused to consider it any further.

Crumpling the page, Jack swiveled his chair round, hand lifted to toss it in the bin, then stopped and returned the paper to his desk, smoothing the creases out with his palm.

Frederick Bligh Bond. The name sprang into his mind, dredged from the recesses of his childhood. The architect who, just before the First World War, had undertaken the first excavations at Glastonbury Abbey, then revealed that he had been directed by messages from the Abbey monks. Had Bond received communications like this? But Bond had been loony. Cracked!

Ripping the sheet of paper in half, Jack dropped the pieces in the bin, slipped into his jacket, and, sketch pad in hand, took the stairs down to the street two at a time.

He stepped out into Benedict Street, fumbling with unsteady fingers to lock his office door. Across the Market Square, the leaded windows of the George & Pilgrims beckoned. A drink, he thought with a shiver, was just what he needed. He’d work on his proposal, and the crowded bar of the old inn would surely make an antidote to whatever it was that had just happened to him.

Tugging his collar up against the wind, he sidestepped a group of adolescent skateboarders who found the smooth pavement round the Market Cross a perfect arena. A particularly fierce gust sent a sheet of paper spiraling past his cheek. He grabbed at it in instinctive self-defense, glancing absently at what he held in his fingers. Pink. A flyer, from the Avalon Society. Glastonbury Assembly Rooms, Saturday, 7:30 to 9:30. An introduction to crystal energy and its healing powers, showing how the chakras and crystals correspond. Make elixirs and learn how to energize your environment.

“Oh, bloody perfect,” he muttered, crumpling the paper and tossing it back to the wind. That was the worst sort of nonsense, just the type of thing that drew the most extreme New Age followers to Glastonbury. Ley lines . . . crop circles . . . Druid magic on Glastonbury Tor, the ancient, conical hill that rose above the town like a beacon . . .

Although Jack, like generations of his family, had grown up in the Tor’s shadow, he’d never given any credence to all the mystical rubbish associated with it, nor to the myths that described Glastonbury as some sort of cosmic mother lode.

So why on earth had he just scribbled what seemed to be a garbled message from some long-dead monk? Was he losing his mind? A delayed reaction to grief, perhaps? He had read about post-traumatic stress syndrome, could that explain what had happened to him? But somehow he sensed it was more than that. For an instant, he saw again the small, precise script, a thing of beauty in itself, and felt a tug of familiarity in the cadence of the language.

He resumed his walk to the pub, then a thought stopped him midstride. What if, what if it were even remotely possible that he had made contact with the dead? Did that mean . . . could it mean he was capable of instigating contact at will? Emily,

No. He couldn’t even allow the idea of such a thing. That way lay madness.

A skateboarder whooshed past him, wheels clacking. “You taking root, mister?” the boy called out. Jack lurched unsteadily on, across the bottom of the High Street towards the George & Pilgrims. As he reached the pub, the heavy door swung open and a knot of revelers pushed past him. An escaping hint of laughter and smoke offered safe haven before the wind snatched sound and scent away; and then, he could have sworn, he heard, faintly, the sound of bells.

The cats slept in the farmyard, taking advantage of the midday warmth of the pale spring sun. Each had its own spot, a flower pot, the sagging step at the kitchen door, the bonnet of the old white van that Garnet Todd used to deliver her tiles, and only the occasional twitch of a feline ear or tail betrayed their awareness of the rustle of mice in the straw.

Garnet stood in the doorway of her workshop, wiping her hands on the leather apron she wore as a protection against the heat of the kiln. She had almost completed her latest commission, the restoration of the tile flooring in a twelfth-century church near the edge of Salisbury Plain. The manufacture of the tiles was painstaking work. The pattern suggested by the few intact bits of floor must be matched, using only the materials and techniques available to the original artisans. Then came the installation, a delicate process requiring hours spent on hands and knees, breathing the dank and musty atmosphere of the ancient church.

But Garnet never minded that. She was most comfortable with old things. Even her work as a midwife, although it had honored the Goddess, had not given her enough visceral connection with the past.

Her farm, a ramshackle place she’d bought more than twenty-five years ago, was proof of how little use she had for the present. The house stood high on the western flank of the Tor, its pitted stone facade in the path of a wind that had scoured down from the hilltop for years beyond memory. The sheep that grazed the grassy slope were her nearest neighbors, and for the most part she preferred their company.

At first she’d meant to put in the electricity and running water, but the years had passed and she’d got used to doing without. Lantern light brought ochre warmth and comforting shadows, and why should she drink the chemically poisoned water the town pumped out of its tanks when the spring on her property bubbled right up from the heart of the sacred hill? Enough had been done in this town to dishonor the old and holy things without her adding to the damage.

A cloud shadow raced down the hillside and for a moment the yard darkened. Garnet shivered. Dion, the old calico cat who ruled the rest of the brood with regal disdain, uncurled herself from the flower pot and came to rub against Garnet’s ankles. “You sense it, too, don’t you, old girl?” Garnet said softly, bending to stroke her. “Something’s brewing.”

Once, long ago, she had caught that scent in the air, once before she had felt that prickle of foreboding, and the memory of the outcome filled her with dread.

Glastonbury had always been a place of power, a pivot point in the ancient battle between the light and the dark. If that delicate balance were disturbed, Garnet knew, not even the Goddess could foresee the consequences.

**********************

Glastonbury did strange things to people, as Nick Carlisle had reason to know. He’d come here for the Festival, part of his plan to take a few months off, see a bit of the world, after leaving Durham with a first in philosophy and theology. On a mild evening in late June he had rounded a bend in the Shepton Mallet Road and seen the great conical hump of the Tor rising above the plain, St. Michael’s Tower on its summit standing squarely against the bloodred western sky.

That had been more than a year ago, and he was still here, working in a New Age bookshop across from the Abbey for little more than minimum wage, living in a caravan in a farmer’s field in Compton Dundon, and trying to forget all that he had left behind.

He often came to the George & Pilgrims for a pint after work. A fine thing, when a pub did duty as his home away from home, but then his caravan didn’t count for much, a place to put the faded jeans, T-shirts, and sweatshirts that made up his meager wardrobe, along with the books he’d brought with him from Durham. The small fridge smelled of sour milk, and the two-ring gas cooker was as temperamental as his mother.

The thought of his mum made him grimace. Elizabeth Carlisle had raised her son alone from his infancy, and in the process had managed to make quite a successful career for herself penning North Country Aga sagas. She had managed her son’s life as efficiently as she did her characters’, and had then pronounced herself affronted by his resentment.

Furious at his mother’s usurping of his responsibilities, he had convinced himself that he would be able to sort out his life as soon as he escaped her orbit. But freedom had not turned out to be the panacea he’d expected: he had no more idea what he wanted to do with his life than he’d had a year ago. He only knew that something held him in Glastonbury, and yet he burned with a restless and unfulfilled energy.

From his corner table, he surveyed the pub’s clientele as he sipped his beer. There was an unusual yuppie element this evening, young men sporting designer suits, accompanied by polished girls in skimpy clothes. Nick could almost feel the rumble of displeasure among the regulars, clustered at the bar in instinctive solidarity.

One of the girls caught his eye and smiled. Nick looked away. Predators in makeup and spandex, girls meant nothing but trouble. First they liked his looks, then, once they found out who his mother was, they saw him as a ready-made meal ticket. But he’d learned his lesson well, and would not let himself fall into that trap again.

Turning his back on the group, he found his attention held by the man sitting alone at the bar’s end. The man was notable not only for his large size and fair hair, but also because his face was familiar. Nick had seen him often in Magdalene Street, he must work near the bookshop, and once or twice they had exchanged a friendly nod. Tonight he sat hunched over his drink, his usually amiable countenance set in a scowl.

Intrigued, Nick saw that he seemed to be writing or sketching on a pad, and that every few moments he raised visibly trembling fingers to brush a lock of hair from his forehead.

When Nick made his way to the bar for a refill, the blond man was staring fixedly at his beer glass, his pen poised over the paper. Nick glanced at the pad. It held neat architectural drawings and figures, and, scrawled haphazardly across the largest sketch, a few lines in what looked to be Latin. It is for my sins Glaston suffered . . . he translated silently.

“You’re a classics scholar?” Nick said aloud, surprised.

“What?” The man blinked owlishly at him. For a moment Nick wondered if he were drunk, but he’d been nursing the same drink since Nick had noticed him.

Nick tapped the sketch pad. “This. I don’t often see anyone writing in Latin.”

Glancing down, the man paled. “Oh, Christ. Not again.”

“Sorry?”

“No, no. It’s quite all right.” The man shook his head and seemed to make a great effort to focus on Nick. “Jack Montfort. I’ve seen you, haven’t I? You work in the bookshop.”

“Nick Carlisle.”

“My office is just upstairs from your shop.” Montfort gestured at Nick’s empty glass. “What are you drinking?”

Montfort bought two more pints, then turned back to Nick. Now he seemed eager to talk. “Working at the bookshop, I suppose you read a good bit?”

“Like a kid in a sweetshop. The manager’s a good egg, turns a blind eye. And I try not to dog-ear the merchandise.”

“I have to admit I’ve never been in the place. Interesting stuff, is it?”

“Some of it’s absolute crap,” Nick replied with a grin. “UFOs. Crop circles, everyone knows that’s a hoax. But some of it . . . well, you have to wonder. . . . Odd things do seem to happen in Glastonbury.”

“You could say that,” Montfort muttered into his beer, his scowl returning. Then he seemed to try to shake off his preoccupation. “You’re not from around here, are you? Do I detect a hint of Yorkshire?”

“It’s Northumberland, actually. I came for the Festival last year”, Nick shrugged, “and I’m still here.”

“Ah, the rock festival at Pilton. Somehow I never managed to get there. I suppose I missed something memorable.”

“Mud.” Nick grinned. “Oceans of it. And slogging about in some farmer’s field, being bitten by midges, drinking bad beer, and queuing for hours to use the toilets. Still . . .”

“There was something,” Montfort prompted.

“Yeah. I’d like to have seen it in its heyday, the early seventies, you know? Glastonbury Fayre, they called it. That must have been awesome. And even that didn’t compare to the original Glastonbury Festival, in terms of quality, not quantity.”

“Original festival?” Montfort repeated blankly.

“Started in 1914 by the composer Rutland Boughton,” Nick answered. “Boughton was extremely talented, his opera The Immortal Hour still holds the record for the longest-running operatic production. All sorts of luminaries were involved in the Festival: Shaw, Edward Elgar, Vaughan Williams, D. H. Lawrence. And Glastonbury had its own contributors to the cultural revival, people like Frederick Bligh Bond and Alice Buckton. . . . And then there was the business of Bond’s friend Dr. John Goodchild and the finding of the ‘Grail’ in Bride’s Well. That caused a few ripples. . . .” Aware that he was babbling, Nick paused and drank the foam off his pint.

Looking up, he saw that Montfort was staring at him. Nick flushed. “Sorry. I get a bit carried away some, “

“You know about Bligh Bond?”

The intensity in Montfort’s voice took Nick by surprise. “Well, it’s a fascinating story, isn’t it? Bond’s knowledge was prodigious, his excavations at the Abbey were proof of that. But I suppose one can’t blame the Church for being a bit uncomfortable with the idea that Bond had received his digging instructions from monks dead five centuries or more.”

“Uncomfortable?” Montfort snorted. “They fired him. He never worked successfully as an architect again and, if I remember rightly, died in poverty. If the man had had an ounce of bloody sense, he’d have kept his mouth shut.”

“He felt he had to share it, though, didn’t he? I’d say Bond was honest to a fault. And I don’t think he ever actually claimed he’d made contact with spirits. He thought he might have merely accessed some part of his own subconscious.”

“Do you believe it’s possible, whatever the source?”

“Bond’s not the only case. There have been well- documented instances where people have known things about the past that couldn’t be accounted for otherwise.” Glancing at the paper Montfort had partially covered with his hand, Nick felt a fizz of excitement. “But you’re not talking hypothetically, are you?”

“This is”, Montfort shook his head, “daft. Too daft to tell anyone. But the coincidence, meeting you here . . . I, “ He looked around, as if suddenly aware of the proximity of other customers, and lowered his voice.

“I was sitting at my desk tonight, and I wrote . . . something. In Latin I haven’t used since I was at school, and I had no memory of writing it. I tore the damned thing up. . . . Then this. . . .” He ran his fingertips across the scrawl on the sketch pad.

“Bugger,” Nick breathed, awed. “I’d swap my mum to have that happen to me.”

“But why me? I didn’t ask for this,” Montfort retorted fiercely. “I’m an architect, but my knowledge of the Abbey is no more than you’d expect from anyone who grew up here. I’m not particularly religious. I’ve never had any interest in spiritualism, or otherworldly things of any sort, for that matter.”

Nick pondered this for a moment. “I doubt these things are random. Maybe you have some connection to the Abbey that you’re not consciously aware of.”

“That’s a big help,” Montfort said, but there was a gleam of humor in his bright blue eyes. “So how do I find out what it is, and why this is happening to me?”

“Maybe I could help. You know it wasn’t Bond who did the actual writing, but his friend, John Bartlett. Bond guided him by asking questions.”

“You want to play Bond to my Bartlett, then?”

“You said you came from Glastonbury. That seems as good a place to start as any.”

“My father’s family’s been in Glastonbury and round about for eons, I should think. He was a solicitor. A large, serious man, very sure of where he stood in the world.” Montfort took a sip of his beer and his voice softened as he continued. “Now, my mother, she was a different sort altogether. She loved stories, loved to play make-believe with us when we were children.”

“Us?”

“My cousins and I. Duncan and Juliet. My aunt and uncle had a penchant for Shakespeare. We always visited them in Cheshire on our holidays. It was a different world. The canals, and then the hills of Wales rising in the distance. . . .”

Once more he fell silent, his eyes half closed. Nick was about to prompt him again, when, without warning, Montfort grasped the pen. His hand began to move steadily across the paper.

Nick translated the Latin as the words began to form. Deo juvante . . . With God’s help . . . you shall make it right. . . . Did that, he wondered, apply to him as well? Could he somehow set right what he had done?

In that instant, Nick knew why he had come to Glastonbury, and he knew why he had stayed.

Faith Wills rested her forehead against the cool plastic of the toilet seat, panting, her eyes swimming with the tears brought on by retching. She had nothing left to throw up but the lining of her stomach, yet somehow she was going to have to pull herself together, go out, and face the smell of her mother’s breakfast.

It was a bacon-and-egg morning, her mum believed all children should go off to school well fortified for the day. They alternated cooked eggs, or porridge, or brown toast and marmite; and on this Thursday morning in March, Faith had struck the worst possible option.

A whiff of bacon crept into the bathroom. Her stomach heaved treacherously just as her younger brother, Jonathan, pounded on the door. “You think you’re effing Madonna in there or something? Hurry bloody up, Faith!”

Without raising her head, Faith said, “Shut up,” but it came out a whisper.

Then her mother’s voice, “Jonathan, you watch your language,” and the crisp rap of knuckles on the door. “Faith, whatever’s the matter with you? You’re going to be late, and make Jon and Meredith late as well.”

“Coming.” Unsteadily, Faith pushed herself up, flushed the toilet, then blew her nose on a piece of toilet tissue. Easing the door open, she found her mum waiting, hands on hips, and beyond her, Jon, and her sister, Meredith, all three faces set in varying degrees of irritation. “What is this, a committee?” she asked, trying for a bit of attitude.

Her mother ignored her, taking her chin in firm fingers and turning her face towards the wan light filtering in from the sitting room. “You’re white as a sheet,” she pronounced. “Are you ill?”

Faith swallowed convulsively against the kitchen smells, then managed to croak, “I’m okay. Just exam nerves.”

Her dad emerged from the bedroom, tying his tie. “How many times have I told you not to leave studying until the last minute? And you know how important your GCSEs, “

“Just let me get my books, okay?”

“Don’t take that tone with me, young lady.” Her dad jerked tight the knot of his tie and reached for her. His fingertips dug into the flesh of her bare arm.

“Sorry,” Faith mumbled, not meeting his eyes. Tugging free, she escaped to the room she shared with her sister and, once inside, leaned against the door, praying for a moment’s peace before Meredith came back. It was a child’s room, she thought, seeing it suddenly anew. The walls were covered with posters of rock stars, the twin beds with bedraggled stuffed animals. Her hockey uniform spilled from her satchel; the sheets of music for that afternoon’s choir practice lay scattered on the floor. All things that had mattered so much to her, all utterly meaningless now.

She wouldn’t be fine, she realized, closing her eyes against the tide of despair that swept over her. Nothing would ever be fine again.

And she couldn’t tell her parents. In her mother’s perfect world, seventeen-year-olds didn’t start the day with their heads in the toilet, and her dad, well, she couldn’t think about that.

She had promised never to tell, and that was all that mattered.

Faith hugged herself, pressing her arms against the new and painful swelling of her breasts. Never, never, never. The word became a litany as she swayed gently.

Ever.

Recenzii

“CROMBIE has laid claim to the literary territory of moody psychological suspense owned by P. D. James and Barbara Vine.”

-The Washington Post

“Intricately layered.”

-The New York Times

“A finely nuanced novel complete with multilayered characters...CROMBIE at the top of her form.”

-Publishers Weekly

“Splendid entertainment.”

-Chicago Tribune

-The Washington Post

“Intricately layered.”

-The New York Times

“A finely nuanced novel complete with multilayered characters...CROMBIE at the top of her form.”

-Publishers Weekly

“Splendid entertainment.”

-Chicago Tribune

Descriere

Scotland Yard Detective Duncan Kincaid's cousin, Jack Montfort, calls from Glastonbury for help on an unusual matter. Revered as the site of an ancient abbey, Glastonbury is also the source of a strong druid power. When Jack comes across an ancient writing revealing something terrible happened long ago--something that can affect the present--Duncan and Sergeant Gemma James search for the truth. (June)