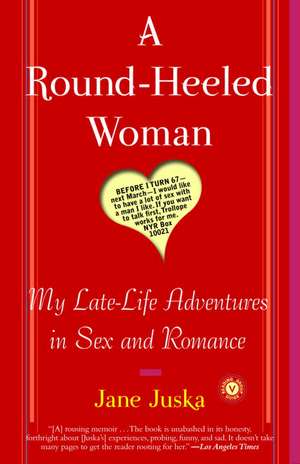

A Round-Heeled Woman: My Late-Life Adventures in Sex and Romance

Autor Jane Juskaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2004

Before I turn 67—next March—I would like to have a lot of sex with a man I like. If you want to talk first, Trollope works for me.

This closing reference was a nod to her favorite author, of course. The response was overwhelming, and Juska took a sabbatical from teaching to meet some of the men who had replied. And since her ad made it clear that she wasn’t expecting just hand-holding, her dates zipped from first base to home plate in record time.

Juska is a totally engaging, perceptive writer, funny and frank about her exploits. It’s high time someone revealed the fact that older single people are as eager for sex and intimacy as their younger counterparts. Jane Juska’s brave, honest memoir will probably raise eyebrows and blood pressure, but it will undoubtedly appeal to the very large audience of grown-up readers who will be fascinated and inspired by her daring adventure.

From the Hardcover edition.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 99.95 lei 3-5 săpt. | +8.41 lei 7-13 zile |

| Vintage Publishing – 30 iun 2004 | 99.95 lei 3-5 săpt. | +8.41 lei 7-13 zile |

| Villard Books – 30 apr 2004 | 106.45 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 106.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.37€ • 21.32$ • 16.85£

20.37€ • 21.32$ • 16.85£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812967876

ISBN-10: 0812967879

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Villard Books

ISBN-10: 0812967879

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Villard Books

Extras

At the Movies

Love is a great comedy, and so is life, when you are not playing one of the roles. —Louise Colet, in a letter to Flaubert

Do you think you’re a nymphomaniac?” Bill wants to know. We sit on my couch close enough for him to grab me should I offer the right answer. Bill obviously thinks there is a strong possibility, and inches closer. He is an attractive man of sixty-one, six years younger than I. He is rich, his jacket cashmere, his trousers a finely worsted wool. He drives a BMW and an Alfa Romeo, though not at the same time. He has brought me a bottle of expensive Chianti, a book he enjoyed, and a cactus fully in bloom. Shortly, we will walk out onto College Avenue and choose a restaurant where we will have dinner. Bill will order everything on the menu that looks interesting, and we will dip into four or five hors d’oeuvres and entrées. We will share a bottle of wine, French. We will return to my cottage, where Bill will continue to quiz me on my sex life.

A few months ago, I turned sixty-seven. My hair is mostly white, with glints of what once was: blond, brown, gray; my face is lined—with wisdom, ahem; my eyes—blue as ever they were—are bifocaled. My teeth, not as sparkling as they used to be, remain American: sturdy, straight, and made to last. Signs of age notwithstanding, dressed—with all of my clothes on—I look pretty good. Undressed is a different matter: my body is not twenty-five or forty-five; it’s not even fifty-five; and, because it has never been interfered with by plastic surgery, what once was firm is loose, what once went up goes down. Intimations of mortality are all about me. Now, though, sitting fully clothed next to Bill, I have possibilities; I can see he thinks so, too. Still, I am an unlikely candidate for the title of Ms. Nymphomania. How is it I am even in the running?

I may turn out to be the hero of my own life or the villain, who knows, but this I know for sure right now: I am easily aroused. And I offer this as a partial answer to Bill’s question. I am aroused by the sight of meadows, the sound of rushing creeks, by print. Not even erotic print. Sometimes, as I lie on my futon reading, say, the Times or The American Scholar, I will feel the familiar tickle between my legs. But mostly, I am aroused by men, parts of men. I love men’s asses, even the ones that aren’t perfect. I am aroused by the sight of John’s neck, of Bill’s forearm, of Sidney’s voice, Robert’s hands, Graham’s legs. Men have fabulous legs, no fat, long muscles. Walking down the street in the summertime, all those men in shorts, is a thrill for me. And I adore penises. They are different one from one another, straight and crooked, long and short, thick and thin, endlessly fascinating at rest or attention. They do wonderful things for me and I do wonderful things for them. Freud wrote that men desire women but women desire men’s desire of them. I suppose so, but, to my mind, women are missing a lot if they’re satisfied only with flared nostrils and heavy breathing.

My heels are very round. I’m an easy lay. An easy sixty-seven-year-old lay. ’Twas not always so. As these pages will show.

Psychologists say that a significant change in one’s life is preceded by a particular, specific event or experience. So it was with mine.

In the fall of 1999, when I was only sixty-six, I sat in the darkened movie theater, malted-milk balls pulsing in their paper bag, and stared at the screen where Eric Rohmer’s soignée heroine smiled coolly across the table at a gentleman clearly her inferior. I popped a ball and once again gave up the notion that I could make them last as long as the movie. With malted-milk balls, my urge was immediate, my discipline in short supply. Aided by the wisdom of advancing age, I no longer crunch the balls as I did when I was thirteen; now, to make them last, I suck on them until they begin to dissolve in my mouth. At exactly the right moment I will bite down (I would never do this to a man; they are so vulnerable there) on the small but rewarding hard center and smile inwardly at the little crunch. Malted-milk balls, like a lot of things, were better when I was young; today’s balls have a chalky taste, and I swear they are smaller. I know they are bad for me, another reason I like them so much. I have become a historian of balls.

Lately—have you noticed?—old people, people living on fixed incomes, people like me, have started to bring their own food to the movies. This is tacky. And it is noisy. The paper bags they bring from home filled with cold popcorn they have popped in their microwaves make noise when the old people rustle around in them. Professional movie sacks, like the one that holds my malted-milk balls, are made of softer material; professional sacks are very quiet. Occasionally, I turn and stare nastily at the miscreant. Mostly, the offender just glares back and continues to rustle. Sometimes, it seems to me, they rustle even louder. And in the dark of the theater, when I shush them, they look at me and their eyes turn red, like wolves’ eyes on nature programs, or like my grandmother’s when I forgot to say thank you. These people are my age; they are my peers. Why do they persist in embarrassing me?

Then there is the talking, which they do whenever they damn well feel like it. At what age—I want to know—does one get to ignore everybody but oneself? How old do you have to be to be rude? With this talking, sometimes, it is a wife explaining the movie to her hard-of-hearing husband, who has refused to wear his hearing aids: “What did he say?” the man will shout, and the wife will answer, in tones loud enough for the people back home to hear, “He said he’s going to kill her.” Then there are the ones who come in late: “I can’t see a thing,” one of them will call, though to whom is unclear since no one answers. And there are the folks who don’t seem to realize the movie has begun and who continue the conversation they started in the parking lot: “I told her she should call her daughter, she lives right down the street. . . .” Once, by mistake, I went to a movie at noontime, unaware that this particular showing was for deaf people. It was the best audience I have ever been privileged to be a part of—totally quiet. I seek them out now.

This movie, this Autumn Tale, engaged my attention at once, so that the claws of the elderly scuttling along the bottoms of their popcorn sacks went unnoticed. I like French films. Everything about them—the scenery, the people, even the plots—is interesting to me. Where the French live, what a middle-class apartment looks like, a café, a hotel room, what the French wear, is fascinating to me. I trust French filmmakers to show me French life. I do not trust American filmmakers to render a true picture of American life. What I see on the screen—a small town, a farm, a prison—is what Hollywood thinks those places ought to look like. So we get the perfect small town in State and Main, not a real one. I don’t learn anything except about Hollywood. The Matrix? The Sixth Sense? Traffic? It seems to me that French movies show the extraordinary in everyday people; American movies show extraordinary people who are, inside, just folks. So in France, in the film Belle de Jour, we have an ordinary, middle-aged, beautiful (she is, after all, French) woman living an ordinary life, who, by virtue of her own ingenuity, lives a secret and very sexy other life. In America, we have Julia Roberts, who, as Erin Brockovich, foul of mouth and pushed-up of bra, wants what we all want: security with a little justice on the side. I’d rather have a sexy secret life. And I will. Watch me.

The French are grown up. The French are cool. They are understated, like in this film, Autumn Tale: a wedding, and the guests, all except for a bold young thing in red, are dressed in the colors of autumn. They are subtle. They are elegant. All the women are tall and thin; that’s French, too. The men? Not one of them can hold a candle to the women even though they are married to them. That is definitely cool, making the men look ordinary, making the women smart to have seen beneath the surface to the steadiness below. Not one of those men is handsome, I thought, as I gazed at the screen. And all the women are. I love it.

The plot, the events of this movie that will change my life, is not unfamiliar: two best friends, women in their late forties, one married, one not. The married friend secretly places an ad in the personals column of the newspaper for her friend and complications ensue. In the vineyards of the Rhône Valley (a very cool place I have never been to), the movie ends happily, though maybe not. The French always leave room for the maybes; ambiguity is another sign of grown-upedness that the French do very well.

Though more than twenty years older than the women in the film, I identify with the unmarried one, the one for whom the ad was secretly placed. The woman is independent and stubborn; she is proud and she is lonely. Divorced and cynical, devoted to her work, she swears she wants nothing to do with men. And yet we see the downturn of her mouth, the nervous rubbing of her fingers, the torn cuticles, the careless tumble of her hair. My own cuticles will take a beating in the months to come. And I hear something of my own voice in the abrupt defensiveness of her speech, her insistence that her work is quite enough. All of us in the audience—young and old, noisy and not—know that the absence of men in her life, while bearable, is not desirable. We can see that she is just plain scared to do anything about it. I know the feeling.

I was divorced thirty years ago. Except for a few skirmishes with men that ended sadly, I lived a full and, in many ways, satisfying life. Teaching was my passion. I was lucky to have found it. It was work that demanded my energy and attention. A single parent, I had a son who demanded the same. And, just in case I found myself tempted, I got fat. No man would look at me. I was safe. Then came 1993. I retired from teaching. My son was grown up and gone. And I was no longer fat. However, men did not come flocking; no man came at all. My stage was bare; in fact, without a classroom I had no stage at all. At age sixty, I had put myself out to pasture after thirty-three years of thriving on a live audience: 150 kids during the day and one feisty son at night. So I was okay. Except there was no one for me to touch and no one to touch me.

From the Hardcover edition.

Love is a great comedy, and so is life, when you are not playing one of the roles. —Louise Colet, in a letter to Flaubert

Do you think you’re a nymphomaniac?” Bill wants to know. We sit on my couch close enough for him to grab me should I offer the right answer. Bill obviously thinks there is a strong possibility, and inches closer. He is an attractive man of sixty-one, six years younger than I. He is rich, his jacket cashmere, his trousers a finely worsted wool. He drives a BMW and an Alfa Romeo, though not at the same time. He has brought me a bottle of expensive Chianti, a book he enjoyed, and a cactus fully in bloom. Shortly, we will walk out onto College Avenue and choose a restaurant where we will have dinner. Bill will order everything on the menu that looks interesting, and we will dip into four or five hors d’oeuvres and entrées. We will share a bottle of wine, French. We will return to my cottage, where Bill will continue to quiz me on my sex life.

A few months ago, I turned sixty-seven. My hair is mostly white, with glints of what once was: blond, brown, gray; my face is lined—with wisdom, ahem; my eyes—blue as ever they were—are bifocaled. My teeth, not as sparkling as they used to be, remain American: sturdy, straight, and made to last. Signs of age notwithstanding, dressed—with all of my clothes on—I look pretty good. Undressed is a different matter: my body is not twenty-five or forty-five; it’s not even fifty-five; and, because it has never been interfered with by plastic surgery, what once was firm is loose, what once went up goes down. Intimations of mortality are all about me. Now, though, sitting fully clothed next to Bill, I have possibilities; I can see he thinks so, too. Still, I am an unlikely candidate for the title of Ms. Nymphomania. How is it I am even in the running?

I may turn out to be the hero of my own life or the villain, who knows, but this I know for sure right now: I am easily aroused. And I offer this as a partial answer to Bill’s question. I am aroused by the sight of meadows, the sound of rushing creeks, by print. Not even erotic print. Sometimes, as I lie on my futon reading, say, the Times or The American Scholar, I will feel the familiar tickle between my legs. But mostly, I am aroused by men, parts of men. I love men’s asses, even the ones that aren’t perfect. I am aroused by the sight of John’s neck, of Bill’s forearm, of Sidney’s voice, Robert’s hands, Graham’s legs. Men have fabulous legs, no fat, long muscles. Walking down the street in the summertime, all those men in shorts, is a thrill for me. And I adore penises. They are different one from one another, straight and crooked, long and short, thick and thin, endlessly fascinating at rest or attention. They do wonderful things for me and I do wonderful things for them. Freud wrote that men desire women but women desire men’s desire of them. I suppose so, but, to my mind, women are missing a lot if they’re satisfied only with flared nostrils and heavy breathing.

My heels are very round. I’m an easy lay. An easy sixty-seven-year-old lay. ’Twas not always so. As these pages will show.

Psychologists say that a significant change in one’s life is preceded by a particular, specific event or experience. So it was with mine.

In the fall of 1999, when I was only sixty-six, I sat in the darkened movie theater, malted-milk balls pulsing in their paper bag, and stared at the screen where Eric Rohmer’s soignée heroine smiled coolly across the table at a gentleman clearly her inferior. I popped a ball and once again gave up the notion that I could make them last as long as the movie. With malted-milk balls, my urge was immediate, my discipline in short supply. Aided by the wisdom of advancing age, I no longer crunch the balls as I did when I was thirteen; now, to make them last, I suck on them until they begin to dissolve in my mouth. At exactly the right moment I will bite down (I would never do this to a man; they are so vulnerable there) on the small but rewarding hard center and smile inwardly at the little crunch. Malted-milk balls, like a lot of things, were better when I was young; today’s balls have a chalky taste, and I swear they are smaller. I know they are bad for me, another reason I like them so much. I have become a historian of balls.

Lately—have you noticed?—old people, people living on fixed incomes, people like me, have started to bring their own food to the movies. This is tacky. And it is noisy. The paper bags they bring from home filled with cold popcorn they have popped in their microwaves make noise when the old people rustle around in them. Professional movie sacks, like the one that holds my malted-milk balls, are made of softer material; professional sacks are very quiet. Occasionally, I turn and stare nastily at the miscreant. Mostly, the offender just glares back and continues to rustle. Sometimes, it seems to me, they rustle even louder. And in the dark of the theater, when I shush them, they look at me and their eyes turn red, like wolves’ eyes on nature programs, or like my grandmother’s when I forgot to say thank you. These people are my age; they are my peers. Why do they persist in embarrassing me?

Then there is the talking, which they do whenever they damn well feel like it. At what age—I want to know—does one get to ignore everybody but oneself? How old do you have to be to be rude? With this talking, sometimes, it is a wife explaining the movie to her hard-of-hearing husband, who has refused to wear his hearing aids: “What did he say?” the man will shout, and the wife will answer, in tones loud enough for the people back home to hear, “He said he’s going to kill her.” Then there are the ones who come in late: “I can’t see a thing,” one of them will call, though to whom is unclear since no one answers. And there are the folks who don’t seem to realize the movie has begun and who continue the conversation they started in the parking lot: “I told her she should call her daughter, she lives right down the street. . . .” Once, by mistake, I went to a movie at noontime, unaware that this particular showing was for deaf people. It was the best audience I have ever been privileged to be a part of—totally quiet. I seek them out now.

This movie, this Autumn Tale, engaged my attention at once, so that the claws of the elderly scuttling along the bottoms of their popcorn sacks went unnoticed. I like French films. Everything about them—the scenery, the people, even the plots—is interesting to me. Where the French live, what a middle-class apartment looks like, a café, a hotel room, what the French wear, is fascinating to me. I trust French filmmakers to show me French life. I do not trust American filmmakers to render a true picture of American life. What I see on the screen—a small town, a farm, a prison—is what Hollywood thinks those places ought to look like. So we get the perfect small town in State and Main, not a real one. I don’t learn anything except about Hollywood. The Matrix? The Sixth Sense? Traffic? It seems to me that French movies show the extraordinary in everyday people; American movies show extraordinary people who are, inside, just folks. So in France, in the film Belle de Jour, we have an ordinary, middle-aged, beautiful (she is, after all, French) woman living an ordinary life, who, by virtue of her own ingenuity, lives a secret and very sexy other life. In America, we have Julia Roberts, who, as Erin Brockovich, foul of mouth and pushed-up of bra, wants what we all want: security with a little justice on the side. I’d rather have a sexy secret life. And I will. Watch me.

The French are grown up. The French are cool. They are understated, like in this film, Autumn Tale: a wedding, and the guests, all except for a bold young thing in red, are dressed in the colors of autumn. They are subtle. They are elegant. All the women are tall and thin; that’s French, too. The men? Not one of them can hold a candle to the women even though they are married to them. That is definitely cool, making the men look ordinary, making the women smart to have seen beneath the surface to the steadiness below. Not one of those men is handsome, I thought, as I gazed at the screen. And all the women are. I love it.

The plot, the events of this movie that will change my life, is not unfamiliar: two best friends, women in their late forties, one married, one not. The married friend secretly places an ad in the personals column of the newspaper for her friend and complications ensue. In the vineyards of the Rhône Valley (a very cool place I have never been to), the movie ends happily, though maybe not. The French always leave room for the maybes; ambiguity is another sign of grown-upedness that the French do very well.

Though more than twenty years older than the women in the film, I identify with the unmarried one, the one for whom the ad was secretly placed. The woman is independent and stubborn; she is proud and she is lonely. Divorced and cynical, devoted to her work, she swears she wants nothing to do with men. And yet we see the downturn of her mouth, the nervous rubbing of her fingers, the torn cuticles, the careless tumble of her hair. My own cuticles will take a beating in the months to come. And I hear something of my own voice in the abrupt defensiveness of her speech, her insistence that her work is quite enough. All of us in the audience—young and old, noisy and not—know that the absence of men in her life, while bearable, is not desirable. We can see that she is just plain scared to do anything about it. I know the feeling.

I was divorced thirty years ago. Except for a few skirmishes with men that ended sadly, I lived a full and, in many ways, satisfying life. Teaching was my passion. I was lucky to have found it. It was work that demanded my energy and attention. A single parent, I had a son who demanded the same. And, just in case I found myself tempted, I got fat. No man would look at me. I was safe. Then came 1993. I retired from teaching. My son was grown up and gone. And I was no longer fat. However, men did not come flocking; no man came at all. My stage was bare; in fact, without a classroom I had no stage at all. At age sixty, I had put myself out to pasture after thirty-three years of thriving on a live audience: 150 kids during the day and one feisty son at night. So I was okay. Except there was no one for me to touch and no one to touch me.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Advance praise for A Round-Heeled Woman

“Feisty, charming, moving and wise, this page-turner of a memoir proves that life for a woman—sexual and otherwise—hardly stops at thirty-nine . . . forty-nine or fifty-nine.” —Cathi Hanauer, editor of The Bitch in the House and author of My Sister’s Bones

“Juska has a good sense of humor, and of course, her favorite writer is Anthony Trollope. She likes the way he treats women in his novels. Let’s wish her a happy birthday and buy her book. I really liked it.” —Liz Smith, “Page Six,” New York Post

“Juska writes well about the sex . . . but even better about the seductions, which take on the luster of years served. Expressive and touching: readers will be rooting for Juska to get all that she wants.” —Kirkus Reviews

“There’s something universal in [Juska’s] love affair with the written word.” —Publishers Weekly

From the Hardcover edition.

“Feisty, charming, moving and wise, this page-turner of a memoir proves that life for a woman—sexual and otherwise—hardly stops at thirty-nine . . . forty-nine or fifty-nine.” —Cathi Hanauer, editor of The Bitch in the House and author of My Sister’s Bones

“Juska has a good sense of humor, and of course, her favorite writer is Anthony Trollope. She likes the way he treats women in his novels. Let’s wish her a happy birthday and buy her book. I really liked it.” —Liz Smith, “Page Six,” New York Post

“Juska writes well about the sex . . . but even better about the seductions, which take on the luster of years served. Expressive and touching: readers will be rooting for Juska to get all that she wants.” —Kirkus Reviews

“There’s something universal in [Juska’s] love affair with the written word.” —Publishers Weekly

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Juska's brave, honest memoir about late-life sexual exploits will probably raise eyebrows and blood pressure, but it will undoubtedly appeal to the very large audience of grown-up readers who will be fascinated and inspired by her daring adventure.

Notă biografică

Jane Juska