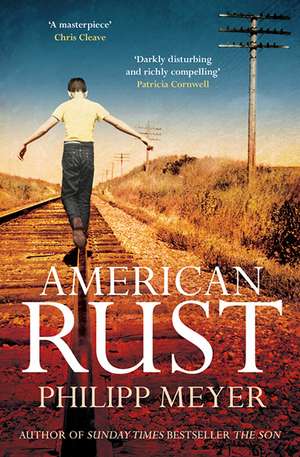

American Rust

Autor Philipp Meyeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 aug 2013

NOW A MAJOR TV SERIES STARRING JEFF DANIELS AND MAURA TIERNEY

An American voice reminiscent of Steinbeck – a debut novel on friendship, loyalty, and love, centering on a murder in a dying Pennsylvania steel town, from the bestselling author of THE SON.

Isaac is the smartest kid in town, left behind to care for his sick father after his mother dies by suicide and his sister Lee moves away. Now Isaac wants out too. Not even his best friend, Billy Poe, can stand in his way: broad-shouldered Billy, always ready for a fight, still living in his mother's trailer. Then, on the very day of Isaac's leaving, something happens that changes the friends' fates and tests the loyalties of their friendship and those of their lovers, families, and the town itself.

Evoking John Steinbeck's novels of restless lives during the Great Depression, American Rust is an extraordinarily moving novel about the bleak realities that battle our desire for transcendence, and the power of love and friendship to redeem us.

'A startlingly mature and impressive debut' KATE ATKINSON

'Darkly disturbing and darkly compelling' PATRICIA CORNWELL

'Written with considerable dramatic intensity and pace' COLM TÓIBÍN

'A masterpiece. The best book to come out of America since The Road' CHRIS CLEAVE

An American voice reminiscent of Steinbeck – a debut novel on friendship, loyalty, and love, centering on a murder in a dying Pennsylvania steel town, from the bestselling author of THE SON.

Isaac is the smartest kid in town, left behind to care for his sick father after his mother dies by suicide and his sister Lee moves away. Now Isaac wants out too. Not even his best friend, Billy Poe, can stand in his way: broad-shouldered Billy, always ready for a fight, still living in his mother's trailer. Then, on the very day of Isaac's leaving, something happens that changes the friends' fates and tests the loyalties of their friendship and those of their lovers, families, and the town itself.

Evoking John Steinbeck's novels of restless lives during the Great Depression, American Rust is an extraordinarily moving novel about the bleak realities that battle our desire for transcendence, and the power of love and friendship to redeem us.

'A startlingly mature and impressive debut' KATE ATKINSON

'Darkly disturbing and darkly compelling' PATRICIA CORNWELL

'Written with considerable dramatic intensity and pace' COLM TÓIBÍN

'A masterpiece. The best book to come out of America since The Road' CHRIS CLEAVE

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 42.80 lei 25-37 zile | +32.90 lei 4-10 zile |

| Simon&Schuster – 29 aug 2013 | 42.80 lei 25-37 zile | +32.90 lei 4-10 zile |

| Spiegel & Grau – 31 dec 2009 | 94.23 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 42.80 lei

Preț vechi: 64.18 lei

-33% Nou

Puncte Express: 64

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.19€ • 8.90$ • 6.89£

8.19€ • 8.90$ • 6.89£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-16 aprilie

Livrare express 14-20 martie pentru 42.89 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781471133701

ISBN-10: 1471133702

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster UK

ISBN-10: 1471133702

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster UK

Descriere

An American voice reminiscent of Steinbeck - a debut novel on friendship, loyalty, and love, centering on a murder in a dying Pennsylvania steel town

Recenzii

Praise for American Rust

“A novel as splendidly crafted and original as any written in recent decades, American Rust is both darkly disturbing and richly compelling. Philipp Meyer’s first novel signals the arrival of a new voice in American letters.”—Patricia Cornwell, author of Scarpetta

“With its strong narrative engine and understated social insight, American Rust is reminiscent of the best of Robert Stone and Russell Banks. Author Philipp Meyer locates the heart of his working class characters without false sentiment or condescension, and their world is artfully described. An extraordinary, compelling novel from a major talent.”—George Pelecanos, author of The Turnaround

“This is strong, clean stuff. Philipp Meyer deserves to be taken seriously.”—Pete Dexter, author of Paper Trails

“Philipp Meyer's American Rust is written with considerable dramatic intensity and pace. It manages an emotional accuracy, a deep and detailed conviction in its depiction of character. It also captures a sense of a menacing society, a wider world in the throes of decay and self-destruction.”—Colm Tóibín, author of The Master

“Meyer has a thrilling eye for failed dreams and writes uncommonly tense scenes of violence . . . Fans of Cormac McCarthy or Dennis Lehane will find in Meyer an author worth watching.”—Publishers Weekly

“A novel as splendidly crafted and original as any written in recent decades, American Rust is both darkly disturbing and richly compelling. Philipp Meyer’s first novel signals the arrival of a new voice in American letters.”—Patricia Cornwell, author of Scarpetta

“With its strong narrative engine and understated social insight, American Rust is reminiscent of the best of Robert Stone and Russell Banks. Author Philipp Meyer locates the heart of his working class characters without false sentiment or condescension, and their world is artfully described. An extraordinary, compelling novel from a major talent.”—George Pelecanos, author of The Turnaround

“This is strong, clean stuff. Philipp Meyer deserves to be taken seriously.”—Pete Dexter, author of Paper Trails

“Philipp Meyer's American Rust is written with considerable dramatic intensity and pace. It manages an emotional accuracy, a deep and detailed conviction in its depiction of character. It also captures a sense of a menacing society, a wider world in the throes of decay and self-destruction.”—Colm Tóibín, author of The Master

“Meyer has a thrilling eye for failed dreams and writes uncommonly tense scenes of violence . . . Fans of Cormac McCarthy or Dennis Lehane will find in Meyer an author worth watching.”—Publishers Weekly

Notă biografică

Philipp Meyer grew up in Baltimore, dropped out of high school, and got his GED when he was sixteen. After spending several years volunteering at a trauma center in downtown Baltimore, he attended Cornell University, where he studied English. Since graduating, Meyer has worked as a derivatives trader at UBS, a construction worker, and an EMT, among other jobs. His writing has been published in McSweeney's, The Iowa Review, Salon.com, and New Stories from the South. From 2005 to 2008 Meyer was a fellow at the Michener Center for Writers in Austin, Texas. He splits his time between Texas and upstate New York.

Extras

Book One

1.

Isaac's mother was dead five years but he hadn't stopped thinking about her. He lived alone in the house with the old man, twenty, small for his age, easily mistaken for a boy. Late morning and he walked quickly through the woods toward town--a small thin figure with a backpack, trying hard to keep out of sight. He'd taken four thousand dollars from the old man's desk; Stolen, he corrected himself. The nuthouse prisonbreak. Anyone sees you and it's Silas get the dogs.

Soon he reached the overlook: green rolling hills, a muddy winding river, an expanse of forest unbroken except for the town of Buell and its steelmill. The mill itself had been like a small city, but they had closed it in 1987, partially dismantled it ten years later; it now stood like an ancient ruin, its buildings grown over with bittersweet vine, devil's tear thumb, and tree of heaven. The footprints of deer and coyotes crisscrossed the grounds; there was only the occasional human squatter.

Still, it was a quaint town: neat rows of white houses wrapping the hillside, church steeples and cobblestone streets, the tall silver domes of an Orthodox cathedral. A place that had recently been well-off, its downtown full of historic stone buildings, mostly boarded now. On certain blocks there was still a pretense of keeping the trash picked up, but others had been abandoned completely. Buell, Fayette County, Pennsylvania. Fayette-nam, as it was often called.

Isaac walked the railroad tracks to avoid being seen, though there weren't many people out anyway. He could remember the streets at shiftchange, the traffic stopped, the flood of men emerging from the billet mill coated with steeldust and flickering in the sunlight; his father, tall and shimmering, reaching down to lift him. That was before the accident. Before he became the old man.

It was forty miles to Pittsburgh and the best way was to follow the tracks along the river--it was easy to jump a coal train and ride as long as you wanted. Once he made the city, he'd jump another train to California. He'd been planning this for a month. A long time overdue. Think Poe will come along? Probably not.

On the river he watched barges and a towboat pass, engines droning. It was pushing coal. Once the boat was gone the air got quiet and the water was slow and muddy and the forests ran down to the edge and it could have been anywhere, the Amazon, a picture from National Geographic. A bluegill jumped in the shallows--you weren't supposed to eat the fish but everyone did. Mercury and PCB. He couldn't remember what the letters stood for but it was poison.

In school he'd tutored Poe in math, though even now he wasn't sure why Poe was friends with him--Isaac English and his older sister were the two smartest kids in town, the whole Valley, probably; the sister had gone to Yale. A rising tide, Isaac had hoped, that might lift him as well. He'd looked up to his sister most of his life, but she had found a new place, had a husband in Connecticut that neither Isaac nor his father had met. You're doing fine alone, he thought. The kid needs to be less bitter. Soon he'll hit California--easy winters and the warmth of his own desert. A year to get residency and apply to school: astrophysics. Lawrence Livermore. Keck Observatory and the Very Large Array. Listen to yourself--does any of that still make sense?

Outside the town it got rural again and he decided to walk the trails to Poe's house instead of taking the road. He climbed steadily along. He knew the woods as well as an old poacher, kept notebooks of drawings he'd made of birds and other animals, though mostly it was birds. Half the weight of his pack was notebooks. He liked being outside. He wondered if that was because there were no people, but he hoped not. It was lucky growing up in a place like this because in a city, he didn't know, his mind was like a train where you couldn't control the speed. Give it a track and direction or it cracks up. The human condition put names to everything: bloodroot rockflower whip-poor-will, tulip bitternut hackberry. Shagbark and pin oak. Locust and king_nut. Plenty to keep your mind busy.

Meanwhile, right over your head, a thin blue sky, see clear to outer space: the last great mystery. Same distance to Pittsburgh--couple miles of air and then four hundred below zero, a fragile blanket. Pure luck. Odds are you shouldn't be alive--think about that, Watson. Can't say it in public or they'll put you in a straitjacket.

Except eventually the luck runs out--your sun turns into a red giant and the earth is burned whole. Giveth and taketh away. The entire human race would have to move before that happened and only the physicists could figure out how, they were the ones who would save people. Of course by then he'd be long dead. But at least he'd have made his contribution. Being dead didn't excuse your responsibility to the ones still alive. If there was anything he was sure of, it was that.

Poe lived at the top of a dirt road in a doublewide trailer that sat, like many houses outside town, on a large tract of woodland. Eighty acres, in this case, a frontier sort of feeling, a feeling of being the last man on earth, protected by all the green hills and hollows.

There was a muddy four-wheeler sitting in the yard near Poe's old Camaro, its three-thousand-dollar paintjob and blown transmission. Metal sheds in various states of collapse, a Number 3 Dale Earnhardt flag pinned across one of them, a wooden game pole for hanging deer. Poe was sitting at the top of the hill, looking out toward the river from his folding chair. If you could find a way to pay your mortgage, people always said, it was like living on God's back acre.

The whole town thought Poe would go to college to keep playing ball, not exactly Big Ten material but good enough for somewhere, only two years later here he was, living in his mother's trailer, sitting in the yard and looking like he intended to cut firewood. This week or maybe next. A year older than Isaac, his glory days already past, a dozen empty beer cans at his feet. He was tall and broad and squareheaded and at two hundred forty pounds, more than twice the size of Isaac. When he saw him, Poe said:

"Getting rid of you for good, huh?"

"Hide your tears," Isaac told him. He looked around. "Where's your bag?" It was a relief to see Poe, a distraction from the stolen money in his pocket.

Poe grinned and sipped his beer. He hadn't showered in days--he'd been laid off when the town hardware store cut its hours and was putting off applying to Wal-Mart as long as possible.

"As far as coming along, you know I've got all this stuff to take care of." He waved his arm generally at the rolling hills and woods in the distance. "No time for your little caper."

"You really are a coward, aren't you?"

"Christ, Mental, you can't seriously want me to come with you."

"I don't care either way," Isaac told him.

"Looking at it from my own selfish point of view, I'm still on goddamn probation. I'm better off robbing gas stations."

"Sure you are."

"You ain't gonna make me feel guilty. Drink a beer and sit down a minute."

"I don't have time," said Isaac.

Poe glanced around the yard in exasperation, but finally he stood up. He finished the rest of his drink and crumpled the can. "Alright," he said. "I'll ride with you up to the Conrail yard in the city. But after that, you're on your own."

From a distance, from the size of them, they might have been father and son. Poe with his big jaw and his small eyes and even now, two years out of school, a nylon football jacket, his name and player number on the front and buell eagles on the back. Isaac short and skinny, his eyes too large for his face, his clothes too large for him as well, his old backpack stuffed with his sleeping bag, a change of clothes, his notebooks. They went down the narrow dirt road toward the river, mostly it was woods and meadows, green and beautiful in the first weeks of spring. They passed an old house that had tipped face-first into a sinkhole--the ground in the Mid-Mon Valley was riddled with old coal mines, some properly stabilized, others not. Isaac winged a rock and knocked a ventstack off the roof. He'd always had a good arm, better than Poe's even, though of course Poe would never admit it.

Just before the river they came to the Cultrap farm with its cows sitting in the sun, heard a pig squeal for a long time in one of the outbuildings.

"Wish I hadn't heard that."

"Shit," said Poe. "Cultrap makes the best bacon around."

"It's still something dying."

"Maybe you should stop analyzing it."

"You know they use pig hearts to fix human hearts. The valves are basically the same."

"I'm gonna miss your factoids."

"Sure you will."

"I was exaggerating," said Poe. "I was being ironic."

They continued to walk.

"You know I would seriously owe you if you came with."

"Me and Jack Kerouac Junior. Who stole four grand from his old man and doesn't even know where the money came from."

"He's a cheap bastard with a steelworker's pension. He's got plenty of money now that he's not sending it all to my sister."

"Who probably needed it."

"Who graduated from Yale with about ten scholarships while I stayed back and looked after Little Hitler."

Poe sighed. "Poor angry Isaac."

"Who wouldn't be?"

"Well to share some wisdom from my own father, wherever you go, you still wake up and see the same face in the mirror."

"Words to live by."

"The old man's been around some."

"You're right about that."

"Come on now, Mental."

They turned north along the river, toward Pittsburgh; to the south it was state forest and coal mines. The coal was the reason for steel. They passed another old plant and its smokestack, it wasn't just steel, there were dozens of smaller industries that supported the mills and were supported by them: tool and die, specialty coating, mining equipment, the list went on. It had been an intricate system and when the mills shut down, the entire Valley had collapsed. Steel had been the heart. He wondered how long it would be before it all rusted away to nothing and the Valley returned to a primitive state. Only the stone would last.

For a hundred years the Valley had been the center of steel production in the country, in the entire world, technically, but in the time since Poe and Isaac were born, the area had lost 150,000 jobs--most of the towns could no longer afford basic services; many no longer had any police. As Isaac had overheard his sister tell someone from college: half the people went on welfare and the other half went back to hunting and gathering. Which was an exaggeration, but not by much.

There was no sign of any train and Poe was walking a step ahead, there was only the sound of the wind coming off the river and the gravel crunching under their feet. Isaac hoped for a long one, which all the bends in the river would keep slow. The shorter trains ran a lot faster; it was dangerous to try to catch them.

He looked out over the river, the muddiness of it, the things buried underneath. Different layers and all kinds of old crap buried in the muck, tractor parts and dinosaur bones. You aren't at the bottom but you aren't exactly at the surface, either. You are having a hard time seeing things. Hence the February swim. Hence the ripping off the old man. Feels like days since you've been home but it has probably only been two or three hours; you can still go back. No. Plenty of things worse than stealing, lying to yourself for example, your sister and the old man being champions in that. Acting like the last living souls.

Whereas you yourself take after your mother. Stick around and you're bound for the nuthouse. Embalming table. Stroll on the ice in February, the cold like being shocked. So cold you could barely breathe but you stayed until it stopped hurting, that was how she slipped in. Take it for a minute and you start to go warm. A life lesson. You would not have risen until now--April--the river gets warmer and the things that live inside you, quietly without you knowing it, it is them that make you rise. The teacher taught you that. Dead deer in winter look like bones, though in summer they swell their skins. Bacteria. Cold keeps them down but they get you in the end.

You're doing fine, he thought. Snap out of it.

But of course he could remember Poe dragging him out of the water, telling Poe I wanted to see what it felt like is all. Simple experiment. Then he was under the trees, it was dark and he was running, mud-covered, crashing through deadfall and fernbeds, there was a rushing in his ears and he came out in someone's field. Dead leaves crackling; he'd been cold so long he no longer felt cold at all. He knew he was at the end. But Poe had caught up to him again.

"Sorry what I said about your dad," he told Poe now.

"I don't give a shit," said Poe.

"We gonna keep walking like this?"

"Like what?"

"Not talking."

"Maybe I'm just being sad."

"Maybe you need to man up a little." Isaac grinned but Poe stayed serious.

"Some of us have their whole lives ahead of them. Others--"

"You can do whatever you want."

"Lay off it," said Poe.

Isaac let him walk ahead. The wind was picking up and snapping their clothes.

"You good to keep going if this storm comes in?"

"Not really," said Poe.

"There's an old plant up there once we get out of these woods. We can find a place to wait it out in there."

From the Hardcover edition.

1.

Isaac's mother was dead five years but he hadn't stopped thinking about her. He lived alone in the house with the old man, twenty, small for his age, easily mistaken for a boy. Late morning and he walked quickly through the woods toward town--a small thin figure with a backpack, trying hard to keep out of sight. He'd taken four thousand dollars from the old man's desk; Stolen, he corrected himself. The nuthouse prisonbreak. Anyone sees you and it's Silas get the dogs.

Soon he reached the overlook: green rolling hills, a muddy winding river, an expanse of forest unbroken except for the town of Buell and its steelmill. The mill itself had been like a small city, but they had closed it in 1987, partially dismantled it ten years later; it now stood like an ancient ruin, its buildings grown over with bittersweet vine, devil's tear thumb, and tree of heaven. The footprints of deer and coyotes crisscrossed the grounds; there was only the occasional human squatter.

Still, it was a quaint town: neat rows of white houses wrapping the hillside, church steeples and cobblestone streets, the tall silver domes of an Orthodox cathedral. A place that had recently been well-off, its downtown full of historic stone buildings, mostly boarded now. On certain blocks there was still a pretense of keeping the trash picked up, but others had been abandoned completely. Buell, Fayette County, Pennsylvania. Fayette-nam, as it was often called.

Isaac walked the railroad tracks to avoid being seen, though there weren't many people out anyway. He could remember the streets at shiftchange, the traffic stopped, the flood of men emerging from the billet mill coated with steeldust and flickering in the sunlight; his father, tall and shimmering, reaching down to lift him. That was before the accident. Before he became the old man.

It was forty miles to Pittsburgh and the best way was to follow the tracks along the river--it was easy to jump a coal train and ride as long as you wanted. Once he made the city, he'd jump another train to California. He'd been planning this for a month. A long time overdue. Think Poe will come along? Probably not.

On the river he watched barges and a towboat pass, engines droning. It was pushing coal. Once the boat was gone the air got quiet and the water was slow and muddy and the forests ran down to the edge and it could have been anywhere, the Amazon, a picture from National Geographic. A bluegill jumped in the shallows--you weren't supposed to eat the fish but everyone did. Mercury and PCB. He couldn't remember what the letters stood for but it was poison.

In school he'd tutored Poe in math, though even now he wasn't sure why Poe was friends with him--Isaac English and his older sister were the two smartest kids in town, the whole Valley, probably; the sister had gone to Yale. A rising tide, Isaac had hoped, that might lift him as well. He'd looked up to his sister most of his life, but she had found a new place, had a husband in Connecticut that neither Isaac nor his father had met. You're doing fine alone, he thought. The kid needs to be less bitter. Soon he'll hit California--easy winters and the warmth of his own desert. A year to get residency and apply to school: astrophysics. Lawrence Livermore. Keck Observatory and the Very Large Array. Listen to yourself--does any of that still make sense?

Outside the town it got rural again and he decided to walk the trails to Poe's house instead of taking the road. He climbed steadily along. He knew the woods as well as an old poacher, kept notebooks of drawings he'd made of birds and other animals, though mostly it was birds. Half the weight of his pack was notebooks. He liked being outside. He wondered if that was because there were no people, but he hoped not. It was lucky growing up in a place like this because in a city, he didn't know, his mind was like a train where you couldn't control the speed. Give it a track and direction or it cracks up. The human condition put names to everything: bloodroot rockflower whip-poor-will, tulip bitternut hackberry. Shagbark and pin oak. Locust and king_nut. Plenty to keep your mind busy.

Meanwhile, right over your head, a thin blue sky, see clear to outer space: the last great mystery. Same distance to Pittsburgh--couple miles of air and then four hundred below zero, a fragile blanket. Pure luck. Odds are you shouldn't be alive--think about that, Watson. Can't say it in public or they'll put you in a straitjacket.

Except eventually the luck runs out--your sun turns into a red giant and the earth is burned whole. Giveth and taketh away. The entire human race would have to move before that happened and only the physicists could figure out how, they were the ones who would save people. Of course by then he'd be long dead. But at least he'd have made his contribution. Being dead didn't excuse your responsibility to the ones still alive. If there was anything he was sure of, it was that.

Poe lived at the top of a dirt road in a doublewide trailer that sat, like many houses outside town, on a large tract of woodland. Eighty acres, in this case, a frontier sort of feeling, a feeling of being the last man on earth, protected by all the green hills and hollows.

There was a muddy four-wheeler sitting in the yard near Poe's old Camaro, its three-thousand-dollar paintjob and blown transmission. Metal sheds in various states of collapse, a Number 3 Dale Earnhardt flag pinned across one of them, a wooden game pole for hanging deer. Poe was sitting at the top of the hill, looking out toward the river from his folding chair. If you could find a way to pay your mortgage, people always said, it was like living on God's back acre.

The whole town thought Poe would go to college to keep playing ball, not exactly Big Ten material but good enough for somewhere, only two years later here he was, living in his mother's trailer, sitting in the yard and looking like he intended to cut firewood. This week or maybe next. A year older than Isaac, his glory days already past, a dozen empty beer cans at his feet. He was tall and broad and squareheaded and at two hundred forty pounds, more than twice the size of Isaac. When he saw him, Poe said:

"Getting rid of you for good, huh?"

"Hide your tears," Isaac told him. He looked around. "Where's your bag?" It was a relief to see Poe, a distraction from the stolen money in his pocket.

Poe grinned and sipped his beer. He hadn't showered in days--he'd been laid off when the town hardware store cut its hours and was putting off applying to Wal-Mart as long as possible.

"As far as coming along, you know I've got all this stuff to take care of." He waved his arm generally at the rolling hills and woods in the distance. "No time for your little caper."

"You really are a coward, aren't you?"

"Christ, Mental, you can't seriously want me to come with you."

"I don't care either way," Isaac told him.

"Looking at it from my own selfish point of view, I'm still on goddamn probation. I'm better off robbing gas stations."

"Sure you are."

"You ain't gonna make me feel guilty. Drink a beer and sit down a minute."

"I don't have time," said Isaac.

Poe glanced around the yard in exasperation, but finally he stood up. He finished the rest of his drink and crumpled the can. "Alright," he said. "I'll ride with you up to the Conrail yard in the city. But after that, you're on your own."

From a distance, from the size of them, they might have been father and son. Poe with his big jaw and his small eyes and even now, two years out of school, a nylon football jacket, his name and player number on the front and buell eagles on the back. Isaac short and skinny, his eyes too large for his face, his clothes too large for him as well, his old backpack stuffed with his sleeping bag, a change of clothes, his notebooks. They went down the narrow dirt road toward the river, mostly it was woods and meadows, green and beautiful in the first weeks of spring. They passed an old house that had tipped face-first into a sinkhole--the ground in the Mid-Mon Valley was riddled with old coal mines, some properly stabilized, others not. Isaac winged a rock and knocked a ventstack off the roof. He'd always had a good arm, better than Poe's even, though of course Poe would never admit it.

Just before the river they came to the Cultrap farm with its cows sitting in the sun, heard a pig squeal for a long time in one of the outbuildings.

"Wish I hadn't heard that."

"Shit," said Poe. "Cultrap makes the best bacon around."

"It's still something dying."

"Maybe you should stop analyzing it."

"You know they use pig hearts to fix human hearts. The valves are basically the same."

"I'm gonna miss your factoids."

"Sure you will."

"I was exaggerating," said Poe. "I was being ironic."

They continued to walk.

"You know I would seriously owe you if you came with."

"Me and Jack Kerouac Junior. Who stole four grand from his old man and doesn't even know where the money came from."

"He's a cheap bastard with a steelworker's pension. He's got plenty of money now that he's not sending it all to my sister."

"Who probably needed it."

"Who graduated from Yale with about ten scholarships while I stayed back and looked after Little Hitler."

Poe sighed. "Poor angry Isaac."

"Who wouldn't be?"

"Well to share some wisdom from my own father, wherever you go, you still wake up and see the same face in the mirror."

"Words to live by."

"The old man's been around some."

"You're right about that."

"Come on now, Mental."

They turned north along the river, toward Pittsburgh; to the south it was state forest and coal mines. The coal was the reason for steel. They passed another old plant and its smokestack, it wasn't just steel, there were dozens of smaller industries that supported the mills and were supported by them: tool and die, specialty coating, mining equipment, the list went on. It had been an intricate system and when the mills shut down, the entire Valley had collapsed. Steel had been the heart. He wondered how long it would be before it all rusted away to nothing and the Valley returned to a primitive state. Only the stone would last.

For a hundred years the Valley had been the center of steel production in the country, in the entire world, technically, but in the time since Poe and Isaac were born, the area had lost 150,000 jobs--most of the towns could no longer afford basic services; many no longer had any police. As Isaac had overheard his sister tell someone from college: half the people went on welfare and the other half went back to hunting and gathering. Which was an exaggeration, but not by much.

There was no sign of any train and Poe was walking a step ahead, there was only the sound of the wind coming off the river and the gravel crunching under their feet. Isaac hoped for a long one, which all the bends in the river would keep slow. The shorter trains ran a lot faster; it was dangerous to try to catch them.

He looked out over the river, the muddiness of it, the things buried underneath. Different layers and all kinds of old crap buried in the muck, tractor parts and dinosaur bones. You aren't at the bottom but you aren't exactly at the surface, either. You are having a hard time seeing things. Hence the February swim. Hence the ripping off the old man. Feels like days since you've been home but it has probably only been two or three hours; you can still go back. No. Plenty of things worse than stealing, lying to yourself for example, your sister and the old man being champions in that. Acting like the last living souls.

Whereas you yourself take after your mother. Stick around and you're bound for the nuthouse. Embalming table. Stroll on the ice in February, the cold like being shocked. So cold you could barely breathe but you stayed until it stopped hurting, that was how she slipped in. Take it for a minute and you start to go warm. A life lesson. You would not have risen until now--April--the river gets warmer and the things that live inside you, quietly without you knowing it, it is them that make you rise. The teacher taught you that. Dead deer in winter look like bones, though in summer they swell their skins. Bacteria. Cold keeps them down but they get you in the end.

You're doing fine, he thought. Snap out of it.

But of course he could remember Poe dragging him out of the water, telling Poe I wanted to see what it felt like is all. Simple experiment. Then he was under the trees, it was dark and he was running, mud-covered, crashing through deadfall and fernbeds, there was a rushing in his ears and he came out in someone's field. Dead leaves crackling; he'd been cold so long he no longer felt cold at all. He knew he was at the end. But Poe had caught up to him again.

"Sorry what I said about your dad," he told Poe now.

"I don't give a shit," said Poe.

"We gonna keep walking like this?"

"Like what?"

"Not talking."

"Maybe I'm just being sad."

"Maybe you need to man up a little." Isaac grinned but Poe stayed serious.

"Some of us have their whole lives ahead of them. Others--"

"You can do whatever you want."

"Lay off it," said Poe.

Isaac let him walk ahead. The wind was picking up and snapping their clothes.

"You good to keep going if this storm comes in?"

"Not really," said Poe.

"There's an old plant up there once we get out of these woods. We can find a place to wait it out in there."

From the Hardcover edition.