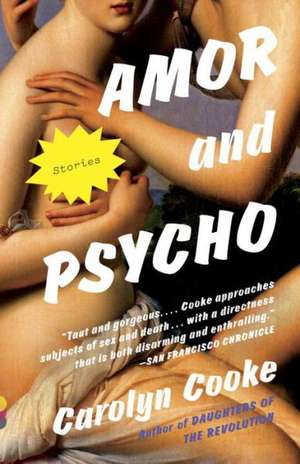

Amor and Psycho: Vintage Contemporaries

Autor Carolyn Cookeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 mai 2014

In “Francis Bacon,” an aspiring writer learns essential lessons from an aging pornographer. In “The Snake,” a restless Jungian analyst sheds one existence after another. In “The Boundary,” a muralist falls in love with a troubled boy from the rez. In the surreal “She Bites,” a man builds an architecturally distinguished doghouse as his wife slowly transforms. And in the transcendent, three-part title story, two best friends face their strange fates, linked by a determination to wrest meaning and coherence from lives spiraling out of control.

At once philosophical and compulsively readable, Amor and Psycho dives into our darkest spaces, confronting the absurdity, poetry and brutality of human existence.

Din seria Vintage Contemporaries

-

Preț: 109.95 lei

Preț: 109.95 lei -

Preț: 101.80 lei

Preț: 101.80 lei -

Preț: 96.52 lei

Preț: 96.52 lei -

Preț: 107.46 lei

Preț: 107.46 lei -

Preț: 91.77 lei

Preț: 91.77 lei -

Preț: 100.35 lei

Preț: 100.35 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 96.11 lei

Preț: 96.11 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 97.34 lei

Preț: 97.34 lei -

Preț: 111.92 lei

Preț: 111.92 lei -

Preț: 117.87 lei

Preț: 117.87 lei -

Preț: 95.92 lei

Preț: 95.92 lei -

Preț: 113.56 lei

Preț: 113.56 lei -

Preț: 101.88 lei

Preț: 101.88 lei -

Preț: 108.09 lei

Preț: 108.09 lei -

Preț: 115.42 lei

Preț: 115.42 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 119.87 lei

Preț: 119.87 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 87.84 lei

Preț: 87.84 lei -

Preț: 99.51 lei

Preț: 99.51 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 99.30 lei

Preț: 99.30 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 103.74 lei

Preț: 103.74 lei -

Preț: 100.98 lei

Preț: 100.98 lei -

Preț: 100.76 lei

Preț: 100.76 lei -

Preț: 89.19 lei

Preț: 89.19 lei -

Preț: 115.94 lei

Preț: 115.94 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 125.13 lei

Preț: 125.13 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 132.88 lei

Preț: 132.88 lei -

Preț: 139.63 lei

Preț: 139.63 lei -

Preț: 93.85 lei

Preț: 93.85 lei -

Preț: 106.45 lei

Preț: 106.45 lei -

Preț: 89.91 lei

Preț: 89.91 lei -

Preț: 107.92 lei

Preț: 107.92 lei -

Preț: 77.02 lei

Preț: 77.02 lei -

Preț: 125.21 lei

Preț: 125.21 lei -

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 99.75 lei -

Preț: 112.11 lei

Preț: 112.11 lei -

Preț: 83.94 lei

Preț: 83.94 lei -

Preț: 97.15 lei

Preț: 97.15 lei -

Preț: 105.82 lei

Preț: 105.82 lei -

Preț: 87.13 lei

Preț: 87.13 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 129.78 lei

Preț: 129.78 lei -

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 110.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 166

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.14€ • 22.60$ • 17.62£

21.14€ • 22.60$ • 17.62£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307741479

ISBN-10: 0307741478

Pagini: 177

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

ISBN-10: 0307741478

Pagini: 177

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

Notă biografică

Carolyn Cooke’s Daughters of the Revolution was listed among the best novels of 2011 by the San Francisco Chronicle and The New Yorker. Her short fiction, collected in The Bostons, won the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award and has appeared in AGNI, The Paris Review and two volumes each of The Best American Short Stories and The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories. She teaches in the MFA writing program at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco.

Recenzii

Praise for Amor and Psycho

“Erotic, whimsical, profound . . . Cooke writes with passion, empathy, and considerable humor as her characters face life-changing issues of divorce, illness, self-destruction, and impending death.”

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Cooke’s stories twist and turn, playing games with language . . . They leave you with something: shards of phrases; a lifetime of attitudes conveyed in a word or an aside; or odd, perfect details that stick in your mind.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Wondrous . . . Within each shadowy narrative, author Carolyn Cooke creates a wholly original voice, perspective, and set of circumstances, making for an altogether rich and remarkable read . . . As all of Cooke’s characters endure the grueling work of letting go, they are occasionally granted redemption, but for the reader, the journey always proves rewarding.”

—Aritzia

“An edgy collection of powerful, engaging, offbeat stories . . . The product of a mature and considerable talent.”

—Booklist

“Cooke takes readers to various cultures and times to examine the anxiety, hopes, struggles, and, above all, the ever-present human quest for love and acceptance . . . A definite page-turner, leaving the discerning reader with memorable character upon which to reflect . . . Cooke keeps readers aware of the travails and triumphs of their humanity.”

—Library Journal

“Erotic, whimsical, profound . . . Cooke writes with passion, empathy, and considerable humor as her characters face life-changing issues of divorce, illness, self-destruction, and impending death.”

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Cooke’s stories twist and turn, playing games with language . . . They leave you with something: shards of phrases; a lifetime of attitudes conveyed in a word or an aside; or odd, perfect details that stick in your mind.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Wondrous . . . Within each shadowy narrative, author Carolyn Cooke creates a wholly original voice, perspective, and set of circumstances, making for an altogether rich and remarkable read . . . As all of Cooke’s characters endure the grueling work of letting go, they are occasionally granted redemption, but for the reader, the journey always proves rewarding.”

—Aritzia

“An edgy collection of powerful, engaging, offbeat stories . . . The product of a mature and considerable talent.”

—Booklist

“Cooke takes readers to various cultures and times to examine the anxiety, hopes, struggles, and, above all, the ever-present human quest for love and acceptance . . . A definite page-turner, leaving the discerning reader with memorable character upon which to reflect . . . Cooke keeps readers aware of the travails and triumphs of their humanity.”

—Library Journal

Extras

Chapter One- Franics Bacon

In the early eighties, I often spent afternoons at Bob’s House, which is what everyone called the twenty-thousand-square-foot Beaux-Arts mansion on East Sixty-seventh Street, said to be the largest private residence in Manhattan. There were always women there, always called “girls,” and Laya looked like all of them to me—soft, fat, seventeen-year-old eager-to-please mouth breathers who signed their contracts with made-up first names and requested, for their take-out lunch, Classic Americans from Burger Heaven. Having grown up poor in a small town myself just three or four years ahead of Laya and her ilk, I felt the pinch of proximity as we strove upstream together toward what I hoped would become a vast gulf between these girls and me. Meanwhile, I lived in terror of being mistaken for one of them. To guard against losing my edge (I hoped to become a writer), I’d refused to take a serious job, preferring the professional twilight zone of the men’s magazine industry. The vulgarity of the writing assignments didn’t bother me; I imagined myself in the position of the Isaac Babel character in his story “Guy de Maupassant” and considered myself lucky that, with my English major and thirty WPM, I hadn’t been forced to become a gofer at a fashion magazine. I also enjoyed Bob’s blurred, autocratic presence, his white shirt unbuttoned to the belt of his sharkskin slacks, the chains around his neck, the long gray chest hair. His empire was worth $300 million that year; he was nearly at the height of his power to shock.

At that time, I needed little, apart from interesting experience, in order to live. While working for Bob, I subsisted on fancy lunches paid for in company scrip, and free cock- tails and hors d’oeuvres at openings for artists the company knew.

My responsibilities entailed exactly what we were doing on this day: traveling across town to Bob’s House, listening to Bob’s orgiastic creative direction, then putting words into the mouths of Babes. Later, from a gray-carpeted cubicle on Broadway near Lincoln Center, I would create implausible erotic monologues (based on implausible true-life experiences) that suggested unspeakably childish innocence, the slight resistance one might encounter parting a raw silk curtain in the dark, accompanied by some subtle but binding statement of adult acquiescence. What better training for a writer than inventing little stories, arousing a casual reader with ordinary language thrillingly unspooled? The story arc was simple, sexual: foreplay, action, climax, denouement. Not that I supposed the men who read our magazine required much in the way of denouement; most of them probably closed the book once they’d spunked. The magazine took great pains—wasted—to expose corporate and government crimes and cover-ups. (We hated cover-ups!) We published the steamier fictions of Roth and Oates.

Working for Bob made me feel like a real writer, commissioned, dared: Give me twenty-four hours and I could give you a story about a lonely coed and a washing machine that could leave you breathless and satisfied.

Exposure to Bob’s antiquities and follies had awakened my capacity for judgment. I felt contemptuous of every lapse in his taste—the carved marble toilets, the glazed fabrics, the white piano, the gallons of gilt. (My own shotgun flat, which I shared with my old college friend Mira, contained no furniture we hadn’t plucked from the street. It was here in this studio, with its cold radiators and scuttling cockroaches, where I did my “real” work at night, brutally scribbling over fresh drafts of my austere prose poems.)

We traveled by taxi across the park to Sixty-seventh Street—an executive, a graphic designer, and a “writer.” In- side the town house, we waited for Bob. We always waited; we waited for hours. It was Bob’s dime; we were Bob’s army, the pornographer’s pornographers. Sometimes we waited all day while topless females cavorted with eunuchy-looking men in European bathing suits by the Roman-style swimming pool, which had been carved out of several venerable rooms. Or we sat in Regency chairs arranged around a fireplace whose panels contained decorative carvings of six-breasted women. Sometimes we waited until we saw Bob and his girlfriend, Kathy, dressed for the evening, descending the stairs and leaving by the front door. (Bob’s face—before the cosmetic work—was sculpted into marble columns along the stairs, and the wall sconces that illuminated the way up to Bob’s “office” were—or at least looked very like—molded testicles of glass.)

When we arrived, Laya—the girl-woman we were going to give away in a contest—was waiting, too, surrounded by the usual surplus of yellow-eyed men in their fifties and six- ties, dyspeptics drinking seltzer water. One of these men immediately offered Laya a weekend in East Hampton. She slid off one strappy sandal, tucked a bare foot under her round bottom and leaned toward her interlocutor. “Is that on the beach?” she asked.

When she saw our trio, she lit up, as if she could have any idea who or what we were, and said, “Hi—I’m Laya!” The “creative team” introduced ourselves, then Ernie, the leering butler, appeared with a tray of vodka drinks. Laya asked for a can of Tab. From another room, or possibly some kind of intercom system, I heard someone say, “Put that nipple up again, or I’ll have to come over and do it for you.”

I resented waiting (dogged by the feeling that I had more important work to do), but Laya seemed to be enjoying her- self the way a hunter enjoys oiling his gun, the way a whale enjoys breaching. We drank our drinks. Laya deployed her long hair as she turned the beam of her attention from one yellow-eyed man to the other. Stray bits of her monologue escaped, which I mentally filed for future use: “Capricorn,” “unicorn,” “nineteen,” “calligraphy.”

Bob eventually sent word via Ernie, and we ascended the stairway of faces and testicles. He stood for Laya, and took her hand. Bob saw himself as an innovator, an idea man, a feminist. He liked to establish this right away. “I’ve arguably done more to advance the status of working-class women than Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem,” he told her.

“Absolutely,” said Bob’s girlfriend, Kathy. Bob had met Kathy—a brilliant dancer with a background in finance and science—at a men’s club in London in 1969, the same year he launched his magazine. Entranced by her beauty and talent, he had bribed his way backstage to her dressing room, where they discussed nuclear fusion. Now Bob and Kathy were funding a team of eighty-five scientists to “work around the clock” in New Mexico; Bob was investing twenty million dollars in a casino and a nuclear power plant. His seemingly unlimited capital came from profits from his magazine, where his innovations to the print centerfold had made him rich, rich, rich!

Bob spoke generally to the room, continuing his feminist theme: “We were the first to show full frontal nudity, the first to show pubic hair, genital penetration. We remain the innovators, the leaders. We pushed the sexual revolution forward.” Bob looked the way he always looked—blurred, boyish, reddish and old, his white silk shirt unbuttoned to his belt. “You are all a part of it,” Bob told us, spreading his arms to include Laya, Kathy, a few cretinous men, the “creative” department, even the paintings on the walls—the Picassos, the El Grecos. We were all a part of it.

One of the themes of his expensive art collection was, naturally, flesh—some of which I recognized from my survey course in art history. Bob owned a number of those fantastically macabre still lifes of Chaim Soutine, flayed rabbits and ducks hanging upside down, pools of blood spilling out among the crystal wineglasses, decanters and blood oranges.

But today Bob had a new enthusiasm—the painter Francis Bacon. I’d never heard of him. A Bacon leaned against a wall. We stood around it, looking down. In the center of the painting, a lone figure howled to the point of implosion. “Bacon,” Bob said, “didn’t paint seriously until his late thirties. You know why? He was looking for a subject that would occupy his attention. This is it. The figure. The orifice.

“Our magazine is inspired by these ideas. It’s vivid and bold, and it’s all about opening up the figure. I want a woman who does not simply lie naked representing a woman. I want to make photographs that immediately connect the viewer with the sensation of being in the presence of this woman. I am not interested in the woman; the woman means what- ever she wants herself to mean. What interests me is the sensation produced by the photograph.”

Laya looked studiously at the painting, as if it might teach her how to be.

Even Kathy’s Rhodesian ridgebacks sniffed around the Bacon. Laya tripped on her heels avoiding one of the dogs, and Bob reached out to grab her. The canvas sighed and fell to the rug. One dog, quivering, escaped from beneath it. Bob picked the painting up and leaned it back against the wall. “Don’t worry,” he said, looking the painting over. “Art canvas. It’s strong.”

We sat, finally, at an oval table, overlooking a platter of raw meat artfully arranged around a bowl filled with tooth- picks. Bob got to the point: “With all this in mind, I want to run a contest. Two weeks in Rio or Paris—someplace like that. Laya’s the grand prize.”

Kathy slowly raised a cube of meat in the air. The Rhodesian ridgebacks trembled with anticipation, then broke into competition.

Bob turned his soft, blurred eyes on Laya and said, “The contest will be tastefully done.” Laya nodded encouragingly at Bob. Of course, of course, tastefully done.

My job, Bob explained, would be to help to shape the story in such a way as to eliminate any tawdry elements. Laya and I would spend an hour together in the “red room” in conversation, from which I would extract her adorable essence, her hopes and dreams, which would appear in the promotional material. One of the cretins handed me a press kit, which contained Laya’s résumé, a high school report card, her height (5 ́2 ̋), her measurements (35ߝ22ߝ35) and her ambitions: “too model and act.”

Bob and Kathy left us to go have dinner at an Italian restaurant famous for its lewd murals and Neapolitan pasta puttanesca. After dinner, Bob and Kathy would stop by some wealthy industrialist’s house for half an hour, as long as Bob ever stayed at a social gathering. He had a phobia about being kidnapped and held for ransom, and also he had little in the way of conversation. But this going out into the evening and coming home at nine or ten was one of the great things, I thought, about Bob. He did not hang out with the other porn kings. He lived and socialized right on East Sixty-seventh Street, and was rather abstemious in his habits.

In the early eighties, I often spent afternoons at Bob’s House, which is what everyone called the twenty-thousand-square-foot Beaux-Arts mansion on East Sixty-seventh Street, said to be the largest private residence in Manhattan. There were always women there, always called “girls,” and Laya looked like all of them to me—soft, fat, seventeen-year-old eager-to-please mouth breathers who signed their contracts with made-up first names and requested, for their take-out lunch, Classic Americans from Burger Heaven. Having grown up poor in a small town myself just three or four years ahead of Laya and her ilk, I felt the pinch of proximity as we strove upstream together toward what I hoped would become a vast gulf between these girls and me. Meanwhile, I lived in terror of being mistaken for one of them. To guard against losing my edge (I hoped to become a writer), I’d refused to take a serious job, preferring the professional twilight zone of the men’s magazine industry. The vulgarity of the writing assignments didn’t bother me; I imagined myself in the position of the Isaac Babel character in his story “Guy de Maupassant” and considered myself lucky that, with my English major and thirty WPM, I hadn’t been forced to become a gofer at a fashion magazine. I also enjoyed Bob’s blurred, autocratic presence, his white shirt unbuttoned to the belt of his sharkskin slacks, the chains around his neck, the long gray chest hair. His empire was worth $300 million that year; he was nearly at the height of his power to shock.

At that time, I needed little, apart from interesting experience, in order to live. While working for Bob, I subsisted on fancy lunches paid for in company scrip, and free cock- tails and hors d’oeuvres at openings for artists the company knew.

My responsibilities entailed exactly what we were doing on this day: traveling across town to Bob’s House, listening to Bob’s orgiastic creative direction, then putting words into the mouths of Babes. Later, from a gray-carpeted cubicle on Broadway near Lincoln Center, I would create implausible erotic monologues (based on implausible true-life experiences) that suggested unspeakably childish innocence, the slight resistance one might encounter parting a raw silk curtain in the dark, accompanied by some subtle but binding statement of adult acquiescence. What better training for a writer than inventing little stories, arousing a casual reader with ordinary language thrillingly unspooled? The story arc was simple, sexual: foreplay, action, climax, denouement. Not that I supposed the men who read our magazine required much in the way of denouement; most of them probably closed the book once they’d spunked. The magazine took great pains—wasted—to expose corporate and government crimes and cover-ups. (We hated cover-ups!) We published the steamier fictions of Roth and Oates.

Working for Bob made me feel like a real writer, commissioned, dared: Give me twenty-four hours and I could give you a story about a lonely coed and a washing machine that could leave you breathless and satisfied.

Exposure to Bob’s antiquities and follies had awakened my capacity for judgment. I felt contemptuous of every lapse in his taste—the carved marble toilets, the glazed fabrics, the white piano, the gallons of gilt. (My own shotgun flat, which I shared with my old college friend Mira, contained no furniture we hadn’t plucked from the street. It was here in this studio, with its cold radiators and scuttling cockroaches, where I did my “real” work at night, brutally scribbling over fresh drafts of my austere prose poems.)

We traveled by taxi across the park to Sixty-seventh Street—an executive, a graphic designer, and a “writer.” In- side the town house, we waited for Bob. We always waited; we waited for hours. It was Bob’s dime; we were Bob’s army, the pornographer’s pornographers. Sometimes we waited all day while topless females cavorted with eunuchy-looking men in European bathing suits by the Roman-style swimming pool, which had been carved out of several venerable rooms. Or we sat in Regency chairs arranged around a fireplace whose panels contained decorative carvings of six-breasted women. Sometimes we waited until we saw Bob and his girlfriend, Kathy, dressed for the evening, descending the stairs and leaving by the front door. (Bob’s face—before the cosmetic work—was sculpted into marble columns along the stairs, and the wall sconces that illuminated the way up to Bob’s “office” were—or at least looked very like—molded testicles of glass.)

When we arrived, Laya—the girl-woman we were going to give away in a contest—was waiting, too, surrounded by the usual surplus of yellow-eyed men in their fifties and six- ties, dyspeptics drinking seltzer water. One of these men immediately offered Laya a weekend in East Hampton. She slid off one strappy sandal, tucked a bare foot under her round bottom and leaned toward her interlocutor. “Is that on the beach?” she asked.

When she saw our trio, she lit up, as if she could have any idea who or what we were, and said, “Hi—I’m Laya!” The “creative team” introduced ourselves, then Ernie, the leering butler, appeared with a tray of vodka drinks. Laya asked for a can of Tab. From another room, or possibly some kind of intercom system, I heard someone say, “Put that nipple up again, or I’ll have to come over and do it for you.”

I resented waiting (dogged by the feeling that I had more important work to do), but Laya seemed to be enjoying her- self the way a hunter enjoys oiling his gun, the way a whale enjoys breaching. We drank our drinks. Laya deployed her long hair as she turned the beam of her attention from one yellow-eyed man to the other. Stray bits of her monologue escaped, which I mentally filed for future use: “Capricorn,” “unicorn,” “nineteen,” “calligraphy.”

Bob eventually sent word via Ernie, and we ascended the stairway of faces and testicles. He stood for Laya, and took her hand. Bob saw himself as an innovator, an idea man, a feminist. He liked to establish this right away. “I’ve arguably done more to advance the status of working-class women than Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem,” he told her.

“Absolutely,” said Bob’s girlfriend, Kathy. Bob had met Kathy—a brilliant dancer with a background in finance and science—at a men’s club in London in 1969, the same year he launched his magazine. Entranced by her beauty and talent, he had bribed his way backstage to her dressing room, where they discussed nuclear fusion. Now Bob and Kathy were funding a team of eighty-five scientists to “work around the clock” in New Mexico; Bob was investing twenty million dollars in a casino and a nuclear power plant. His seemingly unlimited capital came from profits from his magazine, where his innovations to the print centerfold had made him rich, rich, rich!

Bob spoke generally to the room, continuing his feminist theme: “We were the first to show full frontal nudity, the first to show pubic hair, genital penetration. We remain the innovators, the leaders. We pushed the sexual revolution forward.” Bob looked the way he always looked—blurred, boyish, reddish and old, his white silk shirt unbuttoned to his belt. “You are all a part of it,” Bob told us, spreading his arms to include Laya, Kathy, a few cretinous men, the “creative” department, even the paintings on the walls—the Picassos, the El Grecos. We were all a part of it.

One of the themes of his expensive art collection was, naturally, flesh—some of which I recognized from my survey course in art history. Bob owned a number of those fantastically macabre still lifes of Chaim Soutine, flayed rabbits and ducks hanging upside down, pools of blood spilling out among the crystal wineglasses, decanters and blood oranges.

But today Bob had a new enthusiasm—the painter Francis Bacon. I’d never heard of him. A Bacon leaned against a wall. We stood around it, looking down. In the center of the painting, a lone figure howled to the point of implosion. “Bacon,” Bob said, “didn’t paint seriously until his late thirties. You know why? He was looking for a subject that would occupy his attention. This is it. The figure. The orifice.

“Our magazine is inspired by these ideas. It’s vivid and bold, and it’s all about opening up the figure. I want a woman who does not simply lie naked representing a woman. I want to make photographs that immediately connect the viewer with the sensation of being in the presence of this woman. I am not interested in the woman; the woman means what- ever she wants herself to mean. What interests me is the sensation produced by the photograph.”

Laya looked studiously at the painting, as if it might teach her how to be.

Even Kathy’s Rhodesian ridgebacks sniffed around the Bacon. Laya tripped on her heels avoiding one of the dogs, and Bob reached out to grab her. The canvas sighed and fell to the rug. One dog, quivering, escaped from beneath it. Bob picked the painting up and leaned it back against the wall. “Don’t worry,” he said, looking the painting over. “Art canvas. It’s strong.”

We sat, finally, at an oval table, overlooking a platter of raw meat artfully arranged around a bowl filled with tooth- picks. Bob got to the point: “With all this in mind, I want to run a contest. Two weeks in Rio or Paris—someplace like that. Laya’s the grand prize.”

Kathy slowly raised a cube of meat in the air. The Rhodesian ridgebacks trembled with anticipation, then broke into competition.

Bob turned his soft, blurred eyes on Laya and said, “The contest will be tastefully done.” Laya nodded encouragingly at Bob. Of course, of course, tastefully done.

My job, Bob explained, would be to help to shape the story in such a way as to eliminate any tawdry elements. Laya and I would spend an hour together in the “red room” in conversation, from which I would extract her adorable essence, her hopes and dreams, which would appear in the promotional material. One of the cretins handed me a press kit, which contained Laya’s résumé, a high school report card, her height (5 ́2 ̋), her measurements (35ߝ22ߝ35) and her ambitions: “too model and act.”

Bob and Kathy left us to go have dinner at an Italian restaurant famous for its lewd murals and Neapolitan pasta puttanesca. After dinner, Bob and Kathy would stop by some wealthy industrialist’s house for half an hour, as long as Bob ever stayed at a social gathering. He had a phobia about being kidnapped and held for ransom, and also he had little in the way of conversation. But this going out into the evening and coming home at nine or ten was one of the great things, I thought, about Bob. He did not hang out with the other porn kings. He lived and socialized right on East Sixty-seventh Street, and was rather abstemious in his habits.