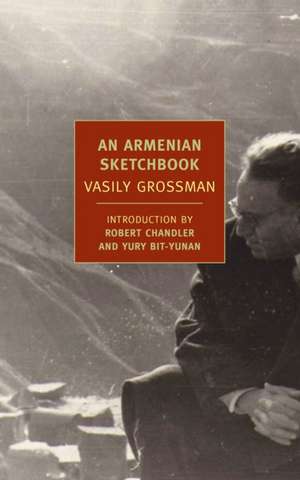

An Armenian Sketchbook: New York Review Books Classics

Autor Vasily Grossman Traducere de Robert Chandler, Elizabeth Chandleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 feb 2013

Few writers had to confront as many of the last century’s mass tragedies as Vasily Grossman, who wrote with terrifying clarity about the Shoah, the Battle of Stalingrad, and the Terror Famine in the Ukraine. An Armenian Sketchbook, however, shows us a very different Grossman, notable for his tenderness, warmth, and sense of fun.

After the Soviet government confiscated—or, as Grossman always put it, “arrested”—Life and Fate, he took on the task of revising a literal Russian translation of a long Armenian novel. The novel was of little interest to him, but he needed money and was evidently glad of an excuse to travel to Armenia. An Armenian Sketchbook is his account of the two months he spent there.

This is by far the most personal and intimate of Grossman’s works, endowed with an air of absolute spontaneity, as though he is simply chatting to the reader about his impressions of Armenia—its mountains, its ancient churches, its people—while also examining his own thoughts and moods. A wonderfully human account of travel to a faraway place, An Armenian Sketchbook also has the vivid appeal of a self-portrait.

Din seria New York Review Books Classics

-

Preț: 88.86 lei

Preț: 88.86 lei -

Preț: 99.24 lei

Preț: 99.24 lei - 16%

Preț: 79.25 lei

Preț: 79.25 lei -

Preț: 77.73 lei

Preț: 77.73 lei -

Preț: 124.55 lei

Preț: 124.55 lei -

Preț: 98.73 lei

Preț: 98.73 lei -

Preț: 83.30 lei

Preț: 83.30 lei -

Preț: 113.45 lei

Preț: 113.45 lei -

Preț: 102.47 lei

Preț: 102.47 lei -

Preț: 81.20 lei

Preț: 81.20 lei -

Preț: 174.64 lei

Preț: 174.64 lei -

Preț: 110.73 lei

Preț: 110.73 lei -

Preț: 119.57 lei

Preț: 119.57 lei -

Preț: 94.01 lei

Preț: 94.01 lei -

Preț: 85.29 lei

Preț: 85.29 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 182.08 lei

Preț: 182.08 lei -

Preț: 142.67 lei

Preț: 142.67 lei -

Preț: 90.72 lei

Preț: 90.72 lei -

Preț: 103.29 lei

Preț: 103.29 lei -

Preț: 113.30 lei

Preț: 113.30 lei -

Preț: 100.59 lei

Preț: 100.59 lei -

Preț: 126.41 lei

Preț: 126.41 lei -

Preț: 107.40 lei

Preț: 107.40 lei -

Preț: 174.03 lei

Preț: 174.03 lei -

Preț: 107.44 lei

Preț: 107.44 lei -

Preț: 89.27 lei

Preț: 89.27 lei -

Preț: 85.34 lei

Preț: 85.34 lei -

Preț: 90.09 lei

Preț: 90.09 lei -

Preț: 119.36 lei

Preț: 119.36 lei -

Preț: 99.60 lei

Preț: 99.60 lei -

Preț: 102.25 lei

Preț: 102.25 lei -

Preț: 127.42 lei

Preț: 127.42 lei -

Preț: 96.27 lei

Preț: 96.27 lei -

Preț: 85.97 lei

Preț: 85.97 lei -

Preț: 136.91 lei

Preț: 136.91 lei -

Preț: 161.86 lei

Preț: 161.86 lei -

Preț: 105.17 lei

Preț: 105.17 lei -

Preț: 88.86 lei

Preț: 88.86 lei -

Preț: 94.83 lei

Preț: 94.83 lei -

Preț: 118.21 lei

Preț: 118.21 lei -

Preț: 87.20 lei

Preț: 87.20 lei -

Preț: 95.45 lei

Preț: 95.45 lei -

Preț: 97.50 lei

Preț: 97.50 lei -

Preț: 111.96 lei

Preț: 111.96 lei -

Preț: 133.18 lei

Preț: 133.18 lei -

Preț: 100.18 lei

Preț: 100.18 lei -

Preț: 75.23 lei

Preț: 75.23 lei -

Preț: 91.13 lei

Preț: 91.13 lei -

Preț: 94.86 lei

Preț: 94.86 lei

Preț: 93.37 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 140

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.87€ • 19.42$ • 15.02£

17.87€ • 19.42$ • 15.02£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781590176184

ISBN-10: 1590176189

Pagini: 135

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

Seria New York Review Books Classics

ISBN-10: 1590176189

Pagini: 135

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

Seria New York Review Books Classics

Notă biografică

Vasily Semyonovich Grossman was born on December 12, 1905, in Berdichev, a Ukrainian town that was home to one of Europe’s largest Jewish communities. In 1934 he published both “In the Town of Berdichev”—a short story that won the admiration of such diverse writers as Maksim Gorky, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Isaak Babel—and a novel, Glyukauf, about the life of the Donbass miners. During the Second World War, Grossman worked as a reporter for the army newspaper Red Star, covering nearly all of the most important battles from the defense of Moscow to the fall of Berlin. His vivid yet sober “The Hell of Treblinka” (late 1944), one of the first articles in any language about a Nazi death camp, was translated and used as testimony in the Nuremberg trials. His novel For a Just Cause (originally titled Stalingrad) was published to great acclaim in 1952 and then fiercely attacked. A new wave of purges—directed against the Jews—was about to begin; but for Stalin’s death, in March 1953, Grossman would almost certainly have been arrested himself. During the next few years Grossman, while enjoying public success, worked on his two masterpieces, neither of which was to be published in Russia until the late 1980s: Life and Fate and Everything Flows. The KGB confiscated the manuscript of Life and Fate in February 1961. Grossman was able, however, to continue working on Everything Flows, a novel even more critical of Soviet society than Life and Fate, until his last days in the hospital. He died on September 14, 1964, on the eve of the twenty-third anniversary of the massacre of the Jews of Berdichev in which his mother had died.

Robert Chandler is the author of Alexander Pushkin and the editor of two anthologies for Penguin Classics: Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida and Russian Magic Tales from

Pushkin to Platonov. His translations of Sappho and Guillaume Apollinaire are published in the Everyman’s Poetry series. His translations from Russian include Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, Everything Flows, and The Road (all published by NYRB Classics); Leskov’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk; and Aleksander Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter. Together with Olga Meerson and his wife, Elizabeth, he has translated a number of works by Andrey Platonov. One of these, Soul, won the 2004 AATSEEL (American Association of Teachers of Slavonic and East European Languages) Prize. His translation of Hamid Ismailov’s The Railway won the AATSEEL Prize for 2007 and received a special commendation from the judges of the 2007 Rossica Translation Prize.

Elizabeth Chandler is a co-translator, with her husband, of Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter; of Vasily Grossman’s Everything Flows and The Road; and of several volumes of Andrey Platonov: The Return, The Portable Platonov, Happy Moscow, and Soul.

Yury Bit-Yunan was born in Bryansk, in western Russia. He graduated from the Russian State University for the Humanities in Moscow, and completed his doctorate on the work of Vasily

Grossman. At present he is lecturing on literary criticism at the Russian State University while continuing to research Grossman’s life and work.

Robert Chandler is the author of Alexander Pushkin and the editor of two anthologies for Penguin Classics: Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida and Russian Magic Tales from

Pushkin to Platonov. His translations of Sappho and Guillaume Apollinaire are published in the Everyman’s Poetry series. His translations from Russian include Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, Everything Flows, and The Road (all published by NYRB Classics); Leskov’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk; and Aleksander Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter. Together with Olga Meerson and his wife, Elizabeth, he has translated a number of works by Andrey Platonov. One of these, Soul, won the 2004 AATSEEL (American Association of Teachers of Slavonic and East European Languages) Prize. His translation of Hamid Ismailov’s The Railway won the AATSEEL Prize for 2007 and received a special commendation from the judges of the 2007 Rossica Translation Prize.

Elizabeth Chandler is a co-translator, with her husband, of Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter; of Vasily Grossman’s Everything Flows and The Road; and of several volumes of Andrey Platonov: The Return, The Portable Platonov, Happy Moscow, and Soul.

Yury Bit-Yunan was born in Bryansk, in western Russia. He graduated from the Russian State University for the Humanities in Moscow, and completed his doctorate on the work of Vasily

Grossman. At present he is lecturing on literary criticism at the Russian State University while continuing to research Grossman’s life and work.

Extras

1

My first impressions of Armenia were from the train, in the morning: greenish-grey rock ߝ in the form not of a mountain or cliff but as a flat deposit, a field of stone. A mountain had died, its skeleton had been scattered over the ground. Time had aged the mountain, it had killed the mountain ߝ and here lay its bones.

Rows of barbed wire stretched along beside the railway line. It took me a while to grasp that the train was running parallel to the Turkish border. I saw a little white house, and then, beside it, a little donkey ߝ not one of our own donkeys but a Turkish donkey. There was no one to be seen. The Turkish soldiers were all asleep.

Armenian village houses, are low, flat-roofed rectangles, put together from large slabs of grey stone. There is no greenery; houses are surrounded not by trees and flowers but by dense scatterings of grey stone. The houses seem not to have been built by human hands. Sometimes a grey stone comes to life and begins to move. Sheep. The sheep too have been engendered by stone, and they probably eat powdered stone and drink stone dust. There is no grass anywhere, no water, nothing but flat, stony steppe ߝ nothing but large, jagged, grey, greenish or black stones.

The peasants are wearing the mighty uniform of all Soviet working folk: thick wadded jackets, grey or black. The people are like the stones they live among, their faces dark both from a natural swarthiness and from being unshaven. Many of them are wearing long white, woollen socks, pulled up over their trousers. The women wear grey headscarves, wound round their heads, covering their mouths and their foreheads as far as their eyes. Even the scarves are the colour of stone.

Then, all of a sudden, I see a couple of women in bright-red dresses, in red blouses, red waistcoats, red sashes and red headscarves. Every part of their dress is a different red, crying out piercingly in its own red voice. These are Kurds ߝ wives to men who have been breeding cattle for thousands of years. Perhaps this is their red mutiny against grey centuries spent amid grey stone.

………………

A man in the compartment with me keeps comparing the heavenly fertility of Georgia with the stones of Armenia. He is young and critically minded ߝ if the conversation turns to the seven-kilometre tunnel built straight through the basalt, he says, “That was built back in the reign of Nicholas II.” Then, he tells me about the opportunities for buying dollars or imperial gold coins; he tells me the black market exchange rate. It seems he really envies those who are serious wheeler-dealers. Later, he tells me about a Yerevan craftsman who fashions metal wreaths adorned with metal leaves. Apparently even the most modest of funerals in Yerevan are attended by two or three hundred people ߝ and there are usually only a few less wreaths than people. This creator of funeral wreaths has become very rich indeed. Then, my neighbour treats me to a pomegranate bought in Moscow. But the journey from Moscow to Yerevan is a long and huge country in itself; when we got on at the Kursk station, my fellow traveller was clean-shaven, but by Yerevan his face was covered with black stubble.

2

On a hill above Yerevan stands a statue of Stalin. No matter where you are in the city, you can clearly see the gigantic bronze marshal. If a cosmonaut from a far-off planet were to see this bronze giant towering over the capital of Armenia, he would understand at once that it is a monument to a great and terrible ruler.

Stalin is wearing a long bronze greatcoat, and he has a military forage cap on his head. One of his bronze hands is tucked beneath the breast (??lapel) of his greatcoat. He is striding along, and his stride is slow, smooth and weighty. It is the stride of a master, the stride of a world ruler; he is in no hurry. Two very different forces come together in him, and this is strange and troubling. He is the expression of a power so vast that it can belong only to God; and he is the expression of a coarse, earthly power, the power of a soldier or government official.

I arrived in Yerevan at the time of the Twenty-Second Party Congress, when the city’s most beautiful street, a broad, straight street lined on either side with plane trees and lit by a central row of streetlamps ߝ was renamed; I arrived when Prospect Stalin was renamed Prospect Lenin.

My Armenian companions, one of whom had once been among the eminent figures entrusted with the task of unveiling the statue of Stalin, seemed very uneasy indeed when I praised the gigantic monument.

My attempts to say a word about Stalin’s role in the construction of the Soviet State were all entirely in vain. My companions would not concede that he had played even the tiniest role in the construction of heavy industry, in the conduct of the war, in the creation of the Soviet apparatus of State. Everything was achieved despite of him, in spite of him. Their lack of objectivity was so glaring that I began to feel an involuntary urge to stand up for Stalin.

In the darkness I walked up to the statue of Stalin. I saw an amazing picture. Dozens of artillery pieces formed a half circle around the base of the monument. With each salvo, the long tongues of flame from the cannons lit up the surrounding mountains and the figure of Stalin would suddenly emerge out of the darkness. Bright incandescent smoke and flame swirled around the bronze feet of the Master. It was as if the Generalissimo were commanding his artillery for the last time. Again and again, fire and thunder split open the darkness; hundreds of soldiers worked frantically away around the cannons. Silence and darkness would return. And then once again a command would be shouted out and the terrible bronze god in a greatcoat would step out from the mountain darkness. No, no, it was impossible not to give this figure his due ߝ he, who had committed countless inhuman crimes, was the leader, the merciless builder of a great and terrible State.

He could not simply be dismissed as a mama dzogla. ‘The son of a bitch’ was no more appropriate a title than ‘Father and Friend of the Peoples of the Earth’.

Officials from the Yerevan City Party Committee informed me that, at a general meeting of collective farmers in a village in the valley of Ararat, someone had put forward a proposal to take down the statue of Stalin. In response, the peasants had said, ‘The State collected a hundred thousand roubles from us in order to erect this statue. Now the State wants to destroy it. By all means, go ahead and destroy it ߝ but give us back our hundred thousand roubles.’ And there had been one old man who had proposed taking down the statue and burying it intact. ‘Who knows? If a new government comes to power, the statue may come in useful. Then we won’t need to fork out a second time.’

When Andreas saw that Stalin had vanished, he was furiously angry. He shook his staff in the air. He attacked drivers; he attacked children; he attacked old Karapet; he attacked students who had come from Yerevan on skiing trips.

For him, Stalin was the man who had defeated the Germans. And the Germans were the allies of the Turks. It followed that the statue of Stalin had been destroyed by Turkish agents. And the Turks had killed Armenian women and children. The Turks had executed Armenian old men. They had brutally annihilated peaceful and entirely innocent people: peasants, workers and craftsmen. They had killed writers, scholars and poets. The Turks had killed Armenian merchants and Armenian beggars; they had killed the Armenian people. The great Russian general Andronik Pasha fought against the Turks. And the Commander in Chief of the Russian Army that destroyed the Turks’ all-powerful allies was Stalin.

Everyone in the village was amused by Andreas’s rage; he had confused two different wars ߝ the first World War and the Second. The crazed old man demanded that the gilded plaster cast of Stalin be returned to the main square in Tsakhkadzor ߝ it was, after all, Stalin who had routed the Germans, who had defeated Hitler. Everyone laughed at the old man: he was insane, whereas the people around him were not insane.

The State took a hundred thousand roubles from us in order to erect that statue. Now the State wants to destroy it. Please go ahead and destroy it ߝ but give us back our hundred thousand roubles.’ One old man, however, suggested taking the statue down and burying it intact: ‘Who knows? He may yet come in useful. It means we won’t have to fork out again if a new government comes to power.’

Recenzii

“Vasily Grossman is the Tolstoy of the USSR.” —Martin Amis

“…it is only a matter of time before Grossman is acknowledged as one of the great writers of the 20th century.” —The Guardian

“Charming. Grossman digresses as nimbly about the master craftsmen of Russian stoves found in the homes of the high-mountain villagers as he does about the touching customs of a rustic wedding he attended. Living among the Armenians, he witnessed a kind of timeless biblical nobility he conveys with artless simplicity in his own work.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Like history, human nature is open-ended; people are capable of doing evil as much as good…[Vasily Grossman] the writer sought to probe the historical fabric and future potential of his society. Perhaps it's because of this stance that his work is finding its way back into print…” —The Nation

“Vasily Grossman’s writing sneaks up on you, its simplicity building to powerful impressions as he records the small things that occur in people's lives as they experience - or endure - larger events.” —The Jewish Chronicle

“…it is only a matter of time before Grossman is acknowledged as one of the great writers of the 20th century.” —The Guardian

“Charming. Grossman digresses as nimbly about the master craftsmen of Russian stoves found in the homes of the high-mountain villagers as he does about the touching customs of a rustic wedding he attended. Living among the Armenians, he witnessed a kind of timeless biblical nobility he conveys with artless simplicity in his own work.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Like history, human nature is open-ended; people are capable of doing evil as much as good…[Vasily Grossman] the writer sought to probe the historical fabric and future potential of his society. Perhaps it's because of this stance that his work is finding its way back into print…” —The Nation

“Vasily Grossman’s writing sneaks up on you, its simplicity building to powerful impressions as he records the small things that occur in people's lives as they experience - or endure - larger events.” —The Jewish Chronicle

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Vasily Grossman, author of Life and Fate, reflects on a season spent in Armenia.