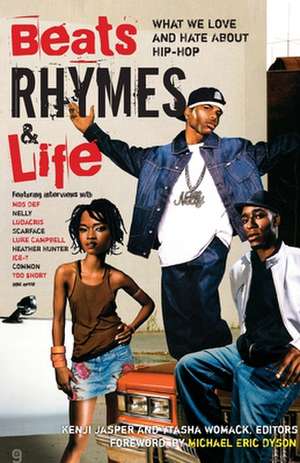

Beats Rhymes & Life: What We Love and Hate about Hip-Hop

Editat de Kenji Jasper, Ytasha Womack Fotografii de Robert H. Johnsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2007

Hip-hop culture has been in the mainstream for years. Suburban teens take their fashion cues from Diddy and expect to have Three 6 Mafia play their sweet-sixteen parties. From the “Boogie Down Bronx” to the heartland, hip-hop’s influence is major. But has the movement taken a wrong turn? In Beats Rhymes and Life, hot journalists Kenji Jasper and Ytasha Womack have focused on what they consider to be the most prominent symbols of the genre: the fan, the turntable, the ice, the dance floor, the shell casing, the buzz, the tag, the whip, the ass, the stiletto, the (pimp’s) cane, the coffin, the cross, and the corner. Each is the focus of an essay by a journalist who skillfully dissects what their chosen symbol means to them and to the hip-hop community.The collection also features many original interviews with some of rap’s biggest stars talking candidly about how they connect to the culture and their fans. With a foreword by the renowned scholar Michael Eric Dyson, Beats Rhymes and Life is an innovative and daring look at the state of the hip-hop nation.

Preț: 112.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.56€ • 22.42$ • 18.04£

21.56€ • 22.42$ • 18.04£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767919777

ISBN-10: 0767919777

Pagini: 307

Dimensiuni: 140 x 211 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Harlem Moon

ISBN-10: 0767919777

Pagini: 307

Dimensiuni: 140 x 211 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Harlem Moon

Notă biografică

KENJI JASPER is a commentator for NPR and has written for The Source, XXL, VIBE, and more. He lives in Brooklyn. YTASHA WOMACK is an editor-at-large for Upscale and has written for the Chicago Tribune, Essence, VIBE, and more. She lives in Chicago.

Extras

NELLY

The Interview 2002

A St. Louis–born rapper whose sing-along hooks etched his name in the annals of pop rap fame, Nelly carved room for midwestern hip-hop on the airwaves. Known for his drawl and lighthearted raps, Nelly steadily dominated in early 2000, shocking an industry that saw profitable hip–hop as purely coastal. He even risked all cool points by doing a country–and–western duet with Tim McGraw, and still came out on top. With four albums in nearly the same number of years, he is the spokesperson for hip–hop as is.

The biggest change [that comes with success] is how people perceive you, ’cause you still do the same things you’ve been doing, but obviously your life is gonna be different. Your life changes from grade school to middle school, from middle school to high school. It's [especially] different for me ’cause I moved around a lot, and in moving around so much the only person that moves around with you is your damn self. I switched like eight schools, so it was like every school I went to I was the only one. Every new household I went to stay in, no matter which side of the family or friends, I was the only one. [So all I know how to do is] treat people how I wanna be treated.

But a lot of people already got you picked when they see you. People are like, “This nigga sold 8.9 million albums, he gotta be a dickhead,” just flat out. Then after they meet a motherfucker they be like, “Oh word, you straight.” But you can’t please everybody. That’s the hardest thing to do. Just to let everybody know you can’t please everybody.

If it’s ten autographs out there I sign eight. Two people are gonna say, “Nelly’s a dickhead” or he’s big–headed or something. Or if it’s thirty girls out there and I give twenty–eight of ’em hugs, the other two are pissed. You can’t please everybody. You just gotta do what you gotta do. If I’m late for somewhere because of time, that’s my fault. If I’m signing autographs for two hours and I was supposed to be at MTV an hour ago, that’s my fault. Sometimes you get in predicaments where you can’t win, and that’s those times where you gotta make judgments for yourself, and I think that’s the hardest part about it.

The Grammy nominations, the Super Bowl, that shit there was bananas. Just my whole career, because I think when you get into it, you just wanna sell records. You just wanna be able to make another record. A lot of people don’t get a chance to make a second record, especially with some new and different shit. Just be able to do another record. That's all we really wanted. But to be able to knock it out and sell so many and have so many people really appreciate what you’re doing…

Everything has been a big moment for us: getting covers of magazines, having your moms flip out because she saw you on the cover of Ebony. Just anything. Just to see their faces, ’cause St. Louis is small but it’s a big city, so everybody knows everybody. [So people are] like, “Damn, that’s little Nell from down the way. This nigga is on the cover of every magazine.” It's a beautiful thing, man.

[When it comes to my music] I don’t wanna remind people that they're having a hard time right now, but I do feel there’s a need to touch on that. So I do have songs that touch on it. But for the most part I wanna keep you vibrant. I wanna keep you upbeat like, “Yeah, I wanna have a good time tonight. Let’s go call some girls. Let’s go kick it. Pop that Nelly in and let’s get it cracking.” We don’t diss nobody. We didn’t come out poking at nobody, saying, “We the best, fuck them!” We just put it out there like, “Yo, here it is. Like it or leave it.” And fortunately we still here.

THE DISGRUNTLED FAN

By Faraji Whalen

Black people would be better off without hip–hop.

That thundering clap you just heard was millions of chew sticks hitting the ground as every b–boy wannabe in America’s jaw dropped. Yet the stunned silence that follows will last about as long as Vanilla Ice’s street cred. And when it ends, there will be a deafening boom of disagreement from every last backpacker, throwbacker, gold–toothed crunk king, and aspiring Damon Dash that will be loud enough to rattle windows like four fifteen-inch subwoofers in the trunk of a ’77 Chevy.

But before the insults and accusations and outrage get started, I have to let you know that I am not Bill O’Reilly. I’m not even Bill Cosby. I’m just through with hip–hop.

I have listened to hip–hop for the vast majority of my life, and for most of that time, I have loved H.E.R. (“Hip–hop in its Essence and Real,” as Common put it). In fact, I still do. But much like your wayward cousin who gets high on embalming fluid and jacks 7–Elevens, my favorite music has gotten out of control. Maybe irreparably so. And while every critic worth his twenty–five cents a word has lamented the figurative death of originality and creativity in hip–hop, it’s the real–life deaths of people in the street that should be worrying pundits. Just as you sometimes secretly wish your cousin would get locked up so he won’t be a danger to the community, I’m really hoping hip–hop goes away for a while to get some rehab before it’s too late.

Much as you still see some good in that cousin of yours, there’s still a lot of good in the music. But somewhere in the past few years, we’ve hit that point at which hip–hop has become so degenerate (while at the same time so hardwired into African American culture) that it is doing irreversible and concrete harm to black people. The ridiculous and overblown black buffoons that major labels are selling to you as real–life Negro heroes to be emulated and worshipped are leading a people astray that barely has one foot on the right path.

The stars of today tell kids that they should be drug dealers, thugs, and womanizers. Because of the unique connection that hip–hop has historically held to realities in the urban streets, the music has the credibility to make these dangerous suggestions extremely influential.

However, we don’t have to accept the idea that these depictions of us are accurate. They are not. Most black people don’t live in poverty. Most of us have access to some kind of decent education. Most of us don’t have to do anything illegal just to get by. The children who listen to and absorb these messages have choices. But because hip–hop has become such a powerful force, it affects the choices these kids make. And far too frequently, these choices are bad ones.

From watching Rap City on any given weekday afternoon, it’s hard to believe the civil rights movement ever existed. The show is a seemingly never–ending parade of escaped slaves who have somehow found their way to a Bentley dealer and a gun shop. These almost coonish depictions do not represent real life for almost any African Americans, and yet the music’s creators continue to insist how “real” they are.

Believe me, if you told me when I was sixteen that shit like that would have ever left my mouth, I would have slapped you for lying to me, and then slapped myself in hopes of changing the future. But roughly ten years later, that’s where I stand. How I came to change my opinion is still something I’m not even certain about. Maybe it’s the way H.E.R. has degenerated in the time that has passed. Maybe it’s the laundry list of rappers who have found themselves in body bags or the fact that there are enough rappers in jail to film a celebrity edition of Oz on location. How many more bottles do we have to pour out onto the street for the likes of Biggie, Pac, Souljah Slim, Jam Master Jay, and Freaky Tah? And how many more rappers have to end up like Shyne, C–Murder, Cassidy, Young Turk, Freaky Zeeky, and Lil’ Kim?

Maybe I just got old and square; got a little money and got conservative (which is what black folks do when we get some money). Whatever the road that got me here, the destination remains the same. Hip–hop has become a problem for black America.

Do the drum patterns, the DJ scratching, or the rapper’s delivery have anything to do with bringing down the race? Of course not. The problem is the culture itself. But before all you stoic defenders of beatboxing, graffiti, and break dancing hop out of your b–boy stance to jump down my throat, understand what I mean by “the culture.”

Hip–hop in 2004 has little to nothing to do with what began in the late 1970s and exploded in the early to mid–1980s. The origins of hip–hop were a boiling stew of different socioeconomic, racial, cultural, and artistic factors that conspired to big–bang a host of new musical possibilities. Hip–hop was not just the music played in the parks and the housing projects in the Bronx and Queensbridge. It was an entire new way of life. I’ll spare the gentle reader the almost requisite journalistic fellating of hip–hop’s pioneers. If you don’t know who Afrika Bambaataa, Kool G Rap, Eric B, and Melle Mel are by now, no amount of ass–kissing on my part is going to make them particularly relevant to the topic of this discussion.

What would black youth be like had hip–hop never come about, or if it had been the flash in the pan that so many thought it would be? As it happened, it was the style, the swagger, and the beat of hip–hop music that triumphed as the reigning cultural force. With staccato verses over breaks and loops came the fashion sense that has evolved from nut–hugging Lees and shell–toe Adidas to Technicolor cross–colors, to jerseys for teams that no longer exist and $300 jeans. There were also the embarrassing synchronized dances of the mideighties: the Reebok, the prep, the cabbage patch, and so on, followed closely by the stoic head nod, the crip walk, and most recently the famed brushing of dirt off the shoulders.

Hip–hop became to this generation what rock and roll once was: a legitimate change in popular culture. Hip–hop once eclipsed country music as the largest–selling single musical genre. Hip–hop–inspired beats and tired amateur rappers have replaced Muzak and celebrity pitchmen to sell TV audiences soggy breakfast cereal and artery–clogging McHeartAttacks. We should be proud. Shouldn’t we?

Along with societal recognition and corporate profits so fat that Lyor Cohen can doggie–paddle through a swimming pool of gold coins like a latter–day Scrooge McDuck has come something much worse: the idea that black youth should conform to and emulate the worst possible racial stereotypes.

The entertainment business machine is marketing these over-the-top ghetto fantasies to white youth as entertainment. The end result: black people, who have been systematically degraded, oppressed, and destroyed, have now willingly picked up the banner of self–destruction and are marching with it like that topless lady in those French revolution portraits. Meanwhile, white people, who make up the vast majority of hip–hop’s listeners (come on, do you really think 5 million black people bought Ja Rule’s albums?), are bombarded with the ideas and images of black buffoonery, amorality, sexuality, and violence as a kind of ghetto fantasy. Now, I’m not one of those conspiracy–believing brothers who think the illuminati and heads of major corporations are holed up in some secret underground lair, plotting to inundate America with the idea that blacks are inferior. If they were, however, they’d be hard pressed to do better than today’s hip–hop.

Let’s take a look at a couple of the major characters in this sad drama. Amos and Andy ain’t got nothing on these boys. We’ll see who the originators are. (The originator title may go to the individual who first popularized the character, as opposed to the one who invented it. After all, Baby may have been the first on the scene with diamonds in his teeth, but it was Paul Wall who really made the shit pop.) And we’ll look at which other rappers have advanced the stereotype. We’ll judge them on a scale of 1 to 10 on the Keep It Real factor, a subscientific indicator of how closely their words match up with their reality, as well as the Damage to the Race factor, which measures exactly what negative effects these depictions have.

The Interview 2002

A St. Louis–born rapper whose sing-along hooks etched his name in the annals of pop rap fame, Nelly carved room for midwestern hip-hop on the airwaves. Known for his drawl and lighthearted raps, Nelly steadily dominated in early 2000, shocking an industry that saw profitable hip–hop as purely coastal. He even risked all cool points by doing a country–and–western duet with Tim McGraw, and still came out on top. With four albums in nearly the same number of years, he is the spokesperson for hip–hop as is.

The biggest change [that comes with success] is how people perceive you, ’cause you still do the same things you’ve been doing, but obviously your life is gonna be different. Your life changes from grade school to middle school, from middle school to high school. It's [especially] different for me ’cause I moved around a lot, and in moving around so much the only person that moves around with you is your damn self. I switched like eight schools, so it was like every school I went to I was the only one. Every new household I went to stay in, no matter which side of the family or friends, I was the only one. [So all I know how to do is] treat people how I wanna be treated.

But a lot of people already got you picked when they see you. People are like, “This nigga sold 8.9 million albums, he gotta be a dickhead,” just flat out. Then after they meet a motherfucker they be like, “Oh word, you straight.” But you can’t please everybody. That’s the hardest thing to do. Just to let everybody know you can’t please everybody.

If it’s ten autographs out there I sign eight. Two people are gonna say, “Nelly’s a dickhead” or he’s big–headed or something. Or if it’s thirty girls out there and I give twenty–eight of ’em hugs, the other two are pissed. You can’t please everybody. You just gotta do what you gotta do. If I’m late for somewhere because of time, that’s my fault. If I’m signing autographs for two hours and I was supposed to be at MTV an hour ago, that’s my fault. Sometimes you get in predicaments where you can’t win, and that’s those times where you gotta make judgments for yourself, and I think that’s the hardest part about it.

The Grammy nominations, the Super Bowl, that shit there was bananas. Just my whole career, because I think when you get into it, you just wanna sell records. You just wanna be able to make another record. A lot of people don’t get a chance to make a second record, especially with some new and different shit. Just be able to do another record. That's all we really wanted. But to be able to knock it out and sell so many and have so many people really appreciate what you’re doing…

Everything has been a big moment for us: getting covers of magazines, having your moms flip out because she saw you on the cover of Ebony. Just anything. Just to see their faces, ’cause St. Louis is small but it’s a big city, so everybody knows everybody. [So people are] like, “Damn, that’s little Nell from down the way. This nigga is on the cover of every magazine.” It's a beautiful thing, man.

[When it comes to my music] I don’t wanna remind people that they're having a hard time right now, but I do feel there’s a need to touch on that. So I do have songs that touch on it. But for the most part I wanna keep you vibrant. I wanna keep you upbeat like, “Yeah, I wanna have a good time tonight. Let’s go call some girls. Let’s go kick it. Pop that Nelly in and let’s get it cracking.” We don’t diss nobody. We didn’t come out poking at nobody, saying, “We the best, fuck them!” We just put it out there like, “Yo, here it is. Like it or leave it.” And fortunately we still here.

THE DISGRUNTLED FAN

By Faraji Whalen

Black people would be better off without hip–hop.

That thundering clap you just heard was millions of chew sticks hitting the ground as every b–boy wannabe in America’s jaw dropped. Yet the stunned silence that follows will last about as long as Vanilla Ice’s street cred. And when it ends, there will be a deafening boom of disagreement from every last backpacker, throwbacker, gold–toothed crunk king, and aspiring Damon Dash that will be loud enough to rattle windows like four fifteen-inch subwoofers in the trunk of a ’77 Chevy.

But before the insults and accusations and outrage get started, I have to let you know that I am not Bill O’Reilly. I’m not even Bill Cosby. I’m just through with hip–hop.

I have listened to hip–hop for the vast majority of my life, and for most of that time, I have loved H.E.R. (“Hip–hop in its Essence and Real,” as Common put it). In fact, I still do. But much like your wayward cousin who gets high on embalming fluid and jacks 7–Elevens, my favorite music has gotten out of control. Maybe irreparably so. And while every critic worth his twenty–five cents a word has lamented the figurative death of originality and creativity in hip–hop, it’s the real–life deaths of people in the street that should be worrying pundits. Just as you sometimes secretly wish your cousin would get locked up so he won’t be a danger to the community, I’m really hoping hip–hop goes away for a while to get some rehab before it’s too late.

Much as you still see some good in that cousin of yours, there’s still a lot of good in the music. But somewhere in the past few years, we’ve hit that point at which hip–hop has become so degenerate (while at the same time so hardwired into African American culture) that it is doing irreversible and concrete harm to black people. The ridiculous and overblown black buffoons that major labels are selling to you as real–life Negro heroes to be emulated and worshipped are leading a people astray that barely has one foot on the right path.

The stars of today tell kids that they should be drug dealers, thugs, and womanizers. Because of the unique connection that hip–hop has historically held to realities in the urban streets, the music has the credibility to make these dangerous suggestions extremely influential.

However, we don’t have to accept the idea that these depictions of us are accurate. They are not. Most black people don’t live in poverty. Most of us have access to some kind of decent education. Most of us don’t have to do anything illegal just to get by. The children who listen to and absorb these messages have choices. But because hip–hop has become such a powerful force, it affects the choices these kids make. And far too frequently, these choices are bad ones.

From watching Rap City on any given weekday afternoon, it’s hard to believe the civil rights movement ever existed. The show is a seemingly never–ending parade of escaped slaves who have somehow found their way to a Bentley dealer and a gun shop. These almost coonish depictions do not represent real life for almost any African Americans, and yet the music’s creators continue to insist how “real” they are.

Believe me, if you told me when I was sixteen that shit like that would have ever left my mouth, I would have slapped you for lying to me, and then slapped myself in hopes of changing the future. But roughly ten years later, that’s where I stand. How I came to change my opinion is still something I’m not even certain about. Maybe it’s the way H.E.R. has degenerated in the time that has passed. Maybe it’s the laundry list of rappers who have found themselves in body bags or the fact that there are enough rappers in jail to film a celebrity edition of Oz on location. How many more bottles do we have to pour out onto the street for the likes of Biggie, Pac, Souljah Slim, Jam Master Jay, and Freaky Tah? And how many more rappers have to end up like Shyne, C–Murder, Cassidy, Young Turk, Freaky Zeeky, and Lil’ Kim?

Maybe I just got old and square; got a little money and got conservative (which is what black folks do when we get some money). Whatever the road that got me here, the destination remains the same. Hip–hop has become a problem for black America.

Do the drum patterns, the DJ scratching, or the rapper’s delivery have anything to do with bringing down the race? Of course not. The problem is the culture itself. But before all you stoic defenders of beatboxing, graffiti, and break dancing hop out of your b–boy stance to jump down my throat, understand what I mean by “the culture.”

Hip–hop in 2004 has little to nothing to do with what began in the late 1970s and exploded in the early to mid–1980s. The origins of hip–hop were a boiling stew of different socioeconomic, racial, cultural, and artistic factors that conspired to big–bang a host of new musical possibilities. Hip–hop was not just the music played in the parks and the housing projects in the Bronx and Queensbridge. It was an entire new way of life. I’ll spare the gentle reader the almost requisite journalistic fellating of hip–hop’s pioneers. If you don’t know who Afrika Bambaataa, Kool G Rap, Eric B, and Melle Mel are by now, no amount of ass–kissing on my part is going to make them particularly relevant to the topic of this discussion.

What would black youth be like had hip–hop never come about, or if it had been the flash in the pan that so many thought it would be? As it happened, it was the style, the swagger, and the beat of hip–hop music that triumphed as the reigning cultural force. With staccato verses over breaks and loops came the fashion sense that has evolved from nut–hugging Lees and shell–toe Adidas to Technicolor cross–colors, to jerseys for teams that no longer exist and $300 jeans. There were also the embarrassing synchronized dances of the mideighties: the Reebok, the prep, the cabbage patch, and so on, followed closely by the stoic head nod, the crip walk, and most recently the famed brushing of dirt off the shoulders.

Hip–hop became to this generation what rock and roll once was: a legitimate change in popular culture. Hip–hop once eclipsed country music as the largest–selling single musical genre. Hip–hop–inspired beats and tired amateur rappers have replaced Muzak and celebrity pitchmen to sell TV audiences soggy breakfast cereal and artery–clogging McHeartAttacks. We should be proud. Shouldn’t we?

Along with societal recognition and corporate profits so fat that Lyor Cohen can doggie–paddle through a swimming pool of gold coins like a latter–day Scrooge McDuck has come something much worse: the idea that black youth should conform to and emulate the worst possible racial stereotypes.

The entertainment business machine is marketing these over-the-top ghetto fantasies to white youth as entertainment. The end result: black people, who have been systematically degraded, oppressed, and destroyed, have now willingly picked up the banner of self–destruction and are marching with it like that topless lady in those French revolution portraits. Meanwhile, white people, who make up the vast majority of hip–hop’s listeners (come on, do you really think 5 million black people bought Ja Rule’s albums?), are bombarded with the ideas and images of black buffoonery, amorality, sexuality, and violence as a kind of ghetto fantasy. Now, I’m not one of those conspiracy–believing brothers who think the illuminati and heads of major corporations are holed up in some secret underground lair, plotting to inundate America with the idea that blacks are inferior. If they were, however, they’d be hard pressed to do better than today’s hip–hop.

Let’s take a look at a couple of the major characters in this sad drama. Amos and Andy ain’t got nothing on these boys. We’ll see who the originators are. (The originator title may go to the individual who first popularized the character, as opposed to the one who invented it. After all, Baby may have been the first on the scene with diamonds in his teeth, but it was Paul Wall who really made the shit pop.) And we’ll look at which other rappers have advanced the stereotype. We’ll judge them on a scale of 1 to 10 on the Keep It Real factor, a subscientific indicator of how closely their words match up with their reality, as well as the Damage to the Race factor, which measures exactly what negative effects these depictions have.

Descriere

In this thoughtful exploration of hip-hop culture, editors Womack and Jasper have collected essays that focus on the most prominent symbols of the genre by journalists who skillfully dissect the evolution of the culture.