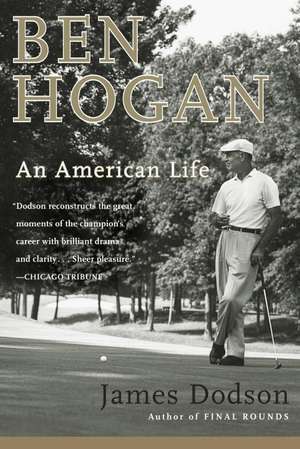

Ben Hogan: An American Life

Autor James Dodsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2005

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

USGA Herbert Warren Wind (2004)

One man is often credited with shaping the landscape of modern golf. Ben Hogan was a short, trim, impeccably dressed Texan whose fierce work ethic, legendary steel nerves, and astonishing triumph over personal disaster earned him not only an army of adoring fans, but one of the finest careers in the history of the sport. Hogan captured a record-tying four U.S. Opens, won five of six major tournaments in a single season, and inspired future generations of professional golfers from Palmer to Norman to Woods.

Yet for all his brilliance, Ben Hogan was an enigma. He was an American hero whose personal life, inner motivation, and famed “secret” were the source of great public mystery. As Hogan grew into a giant on the pro tour, the combination of his cool outward demeanor and invincible, laser-guided accuracy on the golf course froze formidable opponents in their tracks. In 1949, at the peak of his career, Hogan’s mystique was reinforced by a catastrophic automobile accident in which he and his wife, Valerie, were nearly killed after being hit head-on by a Greyhound bus. Doctors predicted Hogan might never walk again – let alone set foot on another golf course. But his miraculous three-year recovery and comeback led to one of the greatest performances in golf history when in 1953 he won the Masters, the U.S. Open, and the British Open (something that’s never been repeated).

In this first-ever family-authorized biography, renowned author James Dodson expertly and emotionally reconstructs Hogan’s complicated life. He discovers an intensely honest man handicapped by self-doubt, buoyed by the determination to prove his own abilities, and unable to escape a long-buried childhood tragedy – the core of the Hogan “secret.” Dodson also reveals both the legendary devotion and eventual strain in Hogan’s sixty-two-year marriage, and a Hogan rarely seen by the public: a warm, jovial man whose charitable spirit and sharp business sense enabled him to build the powerful golf equipment company bearing his name to this day. Ben Hogan: A Life is the authoritative inside portrait golf fans have long awaited.

Preț: 137.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 206

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.23€ • 27.39$ • 21.66£

26.23€ • 27.39$ • 21.66£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767908634

ISBN-10: 0767908635

Pagini: 527

Dimensiuni: 141 x 210 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767908635

Pagini: 527

Dimensiuni: 141 x 210 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

JAMES DODSON is the author of bestselling Final Rounds, which was named the Golf Book of the Year by the International Network of Golf in 1996. He is also the author of The Road To Somewhere: Travels With A Young Boy Through An Old World, as well as Faithful Travelers, The Dewsweepers, and A Golfer’s Life, a collaboration with Arnold Palmer that was a New York Times bestseller. A multiple winner of the prestigious Golf Writers of America Award for his column in Golf Magazine, and numerous other literary prizes, Dodson lives with his wife and children on the coast of Maine.

Extras

Chapter One

God's Country

Dating from the late 1880s, a U.S. federal surveying map of west Texas lands summarizes the isolated village of Dublin rather simply and starkly as "a moderately prosperous railhead located on the edge of formerly occupied Indian territories."

In fact, since its establishment by Irish immigrant farmers a decade before the outbreak of the Civil War, eighty miles southwest of Fort Worth and nearly at the geographical center of the state of Texas, Dublin had been an oasis of protection and shade in an unforgiving sea of scrub oaks and native grasslands. It occupied a limestone rise of forested hills that were notable for their clear running creeks and abundance of wild turkey, prairie chicken, and free-ranging buffalo.

The Comanche, Kiowa, Lipan, and Apache tribes who hunted these bleak surrounding lands, undisturbed for centuries before white settlers pushed into the region, were more than a little reluctant to give them up to the newcomers, and thus Dublin's early town records are filled with vivid accounts of deadly skirmishes between uninvited homesteaders and native inhabitants, family massacres, and revenge killings.

As late as the start of the twentieth century, surviving elements of these "pacified" native peoples periodically committed violent raids on Dublin township for horses and cows, and a year seldom passed without the murder of a farmer or disappearance of a town resident caught unaware in some isolated outlying area. "My grandmother used to say this was God's country," remembers a modern resident of Dublin whose family roots burrow back to the town's formation. "He put this nice little Christian town smack in the middle of a country that was meaner than hell. Reckon only He could truly love it."

One popular account of how Dublin got its name holds that it came from the shouted alert to "double in the wagons! Indians a'comin'!" though the abundance of Irish surnames in local graveyards suggests the founding fathers were probably more intent upon honoring their distant homeland when Dublin actually appeared on government land maps around 1860. A less likely if more colorful theory holds that the name derived from the raucous Double Inn Hotel that opened up about the time the railroad arrived to serve the needs of a more prosperous crossroads economy, a notorious roadhouse that specialized in strong drink and cheap beds.

Five years after the Yuma Stagecoach Line made Dublin a regular stop in 1874, the Texas Central Railroad surveyed a line straight through the heart of town and opened a small depot there in 1881, prompting an influx of cattlemen and cotton farmers aiming to seek their fortunes on the edge of a wild new country. One of those who came to town was a young, rawboned Mississippian looking for a new start. William Alexander Hogan had spent a year serving as a blacksmith in a Confederate cavalry unit before taking a bride four years his senior and settling down to try to raise cotton on rented land back in Mississippi. After five years of hard tenant labor that left the Hogans with little or nothing to show for their efforts, William and Cinthia Hogan pulled up stakes and joined the migration to the promised land of west Texas, arriving in Dublin sometimes after 1870 with their four young children: William, Josephine, Martha, and Mary. According to Sunday school records, they joined the First Baptist Church almost immediately upon arriving in town, and William abandoned farming in favor of the trade he'd learned in the Confederate Army.

Whether by chance or design, the opening of a new blacksmith shop on Elm Street, just a block or so from the center of town, was fortuitously timed because the same railroad that brought settlers into the formerly untamed region also brought cattle ranchers and cotton farmers in growing numbers, people who relied heavily on the horse for their livelihoods and transportation needs.

On February 2, 1885, a fifth and final child was born to the Hogans, a solemn dark-eyed boy they called Chester, possibly after the outgoing president of the United States. At an early age, according to early family lore--what little of it managed to pass down the line--Chester Hogan was drawn to the dust and bustle of his father's workplace, often spending his days at the blacksmith shop tending horses and watching customers come and go. He was said to be an unusually sweet-dispositioned child given to periods of prolonged silence.

In 1889 a spur of the larger Fort Worth-Rio Grande Railroad reached Dublin and an opera house opened its ornate doors, featuring dance hall girls and the kind of rowdy frontier melodramas that soon attracted patrons from as far away as Fort Worth and Dallas. One of those who found himself attracted to the town's mix of the Old West and the new ways was Sam Houston Prim, a former bookstore owner who contracted to produce and bottle a carbonated concoction that was all the rage down in Waco, a sweet soda beverage called Dr. Pepper. Sensing an opportunity to get the jump on merchants restricted to peddling the newfangled soda drink from their traditional lunch counters around the Lone Star State, Prim opened his small bottling plant with the greater ambition to make Dr. Pepper available at every general store and grocery purveyor in west Texas. To do so, he hired his brother and a nephew to mix chilled carbonated water and flavored syrup in Hutchinson bottles, which could then be sealed with wire corks and shipped imperishably anywhere there were good roads or rail lines. The idea caught on like a fever, and Prim was soon expanding his operation and looking for extra hands to bottle and ship his soda. In due course, Prim hired the quiet but hardworking youngest son of William Hogan to wash returned bottles, refill and cork them, and crate them up for shipment.

Chester Hogan was believed to be twenty years old and already married the spring he briefly left his father's blacksmith shop to bottle Dr. Pepper, and in a famous photograph that the Dublin Progress newspaper published in 1955--half a century later--the youngest Hogan appears erect and taciturn, with an almost Lincoln-like solemnity and bearing about the eyes, remarkably like the two sons he would father within a decade. Not long after the photograph appeared in print, the newspaper's editor received a pair of politely worded letters from golfer Ben Hogan, the first requesting a "glossy print of this original picture at your earliest possible convenience," the second a short while later expressing the letter writer's deep appreciation for a prompt reply and dispatch of the photograph in question. Neither letter made even passing reference to the fact that the man in the photograph was Ben Hogan's father.

Chester Hogan, in any case, was married to the former Clara Williams, third child of a Dublin cotton buyer who grew up in a rented house on nearby Grafton Street, a short time after he went to work for Sam Prim. Her father, Ben Williams, a prominent member of the Baptist church, was remembered as being a fastidious dresser and a quick-witted man who could instantly work out the most complicated math problems in his head even while simultaneously transacting purchases of bundled bails of raw cotton that were brought from the fields by the wagonload to the Dublin train depot. It was Williams's job to grade and purchase bails of raw cotton fiber, then mark and ship them on for processing to northern clothing and thread manufacturing companies. For his trouble, he collected 10 percent of every consummated purchase.

Cotton was king across much of the American South in those days, and Ben Williams had social ambitions that probably didn't include his pretty, spirited daughter marrying the silent heir of the village smithy shop.

As a Fort Worth reporter snooping around in Ben Hogan's mysterious early life in the late 1950s first discovered--but chose not to reveal--there was apparently no marriage certificate between Chester Hogan and Clara Williams filed anywhere in the courthouse records of Erath or neighboring Comanche County, leading some to surmise that the young couple may simply have eloped or quietly gone off and married in a hurry, owing to an impending arrival. In any case, from family sources it's known that Clara was eighteen in 1908 when she gave birth for the first time to a boy she rather fancifully named Royal Dean. Two years later a daughter was born at home, probably at the young couple's modest wooden frame house on Camden Street. Projecting her ambitions for a more refined life on her first and only female child, Clara named the girl Chester Princess.

Finally, on August 13, 1912, a few days after the Bull Moose Party nominated Theodore Roosevelt for president and advocated a platform promoting women's suffrage and sweeping election reform, Clara Hogan delivered a second son at the new women's infirmary in nearby Stephensville, the county seat. For reasons unclear--possibly having to do with her natural distrust of strangers or the dying western tradition that held all newborns should be properly named at home (it was bad luck to do otherwise)--Mama Hogan chose not to give the baby a formal name until she brought her infant male home to Dublin.

Both Royal Dean and Princess were remembered by Dublin elders as lively babies who seemed to possess their mama's extroverted nature, but the third Hogan issue had both his father's calm and watchful personality and his mother's imposing blue-gray eyes. Clara eventually decided to call him William Ben Hogan, after both his grandfathers, the diligent blacksmith and the enterprising cotton broker, a pretty good choice considering the way young Bennie turned out in life.

Except for his modestly phrased letters of inquiry and gratitude to the Dublin Enterprise, sent and received during the summer of 1955--the year he just missed winning a record fifth National Open and announced his intention to "retire" from full-time professional golf to pursue "other interests"--Ben Hogan rarely acknowledged his blood connection to the rough little pioneer railhead of his birth on the edge of former Indian country. In light of what followed nine years after his birth, it's not too surprising that he flatly refused to ever publicly mention the circumstances that drove the family from the town, and never even spoke of it to the woman he chose to court and marry until his own mother let the secret out many years later.

"One of the first things I learned about our family was that nobody talked about the past or wrote things down unless it was completely necessary, and certainly not that," reflects Jacqueline Hogan Towery, Royal Hogan's only daughter and one of two nieces Ben Hogan came to regard as if they were his own daughters. "For the Hogans, Dublin was essentially the end of the line. And the way they looked at it, if you wrote something down it might later be used against you. So there was no chance of family history ever being written. Growing up, I never heard my grandmother say anything about my grandfather, her late husband. Chester was the man never mentioned in our house. All we knew was that he'd somehow gotten sick and eventually died. And then she'd brought her family to Fort Worth to get on with things, to start a new life."

Before that abrupt and violent partitioning from their birthplace took place, by all accounts the three Hogan children experienced fairly ordinary and even happy childhoods in the quiet oak-shaded streets of Dublin. Once Chester returned to take over his father's blacksmith shop on Elm Street, shoeing horses provided sufficient income to permit Chester and Clara to own a second small rental house, and for many years the family wasn't anywhere nearly as destitute as later accounts of Hogan's early childhood days present them as being. On the contrary, life for the Hogan charges appears to have been something of a rural American idyll, with picnics by Clear Creek and evening suppers at the Baptist church. An early newspaper advertisement for the family business, for example, includes a photograph of the Hogan children bundled together on a pony wagon draped with a Fourth of July parade sign that cheerfully reads: "pappa's a blacksmith. let hogan shoe your horse!"

The oldest boy, Royal Hogan, was remembered as a natural athlete who organized neighborhood teams and pitched a mean sandlot baseball game; Princess, who had her mother's gregarious personality, stern good looks, and no shortage of the Williams charm and ambition, sang at church and even earned a few bit parts in musical productions at the old Dublin Opera Hall. Neighbors from those years who knew the family often remembered that quiet little Bennie Hogan seemed to be his father's boy to the core, a thoughtful lad who was shy but unfailingly polite around adults, a bit of a happy loner who loved to poke around his father's busy blacksmith shop, where he calmed the horses as they waited to be shoed and fed scraps of his lunch to the village dogs that always congregated there on hot summer days. Tellingly, decades later, Ben Hogan's favorite keepsake from this faraway childhood--his most prized family possession--was a small black-and-white photograph that shows him sitting peacefully on his father's lap, astride a chestnut mare. Bennie was maybe a year old at the time, being cradled between his father's belt and the saddle horn, already clutching the reins like a true son of the West. Father and son are both looking away from the camera's lens, as if scanning some unknown horizon, but the spiritual connection between them is unmistakable. Their expressions and profiles are serenely calm, and nearly identical.

As his father had been, young Bennie was a bit undersized for his age, the classic neighborhood runt, and some recalled that he seemed destined to grow up in Royal's shadow, reduced to playing the "pigtail" during sandlot games where Royal was always pitching, the extra boy who chased down errant throws the catcher missed, just waiting for his chance to get invited into the game. For other entertainments, the Hogan children swam in Clear Creek and went to the open-air movie theater just off Dublin's dusty main square on Friday nights, plunking down a nickel for a seat on a hard bench to watch Douglas Fairbanks in The Knickerbocker Buckeroo or Charlie Chaplin's Shoulder Arms. Even then, Bennie Hogan shared his big sister Princess's fascination with the magic of Hollywood movies, in thrall of a world of glamour and fortune that felt about as far away as one could possibly get from the dust and heat of God's country and their father's already dwindling blacksmith trade.

The year 1920 was a watershed year for America in general and for Texas in particular. The "Great War to end all wars" had claimed the lives of five thousand Texans but ended with the signing of the Armistice in 1918. By 1920 the war's end had produced a manufacturing boom and a revolution in goods and services back home that promised to transform the American landscape as never before, beginning and ending with Main Street itself.

From the Hardcover edition.

God's Country

Dating from the late 1880s, a U.S. federal surveying map of west Texas lands summarizes the isolated village of Dublin rather simply and starkly as "a moderately prosperous railhead located on the edge of formerly occupied Indian territories."

In fact, since its establishment by Irish immigrant farmers a decade before the outbreak of the Civil War, eighty miles southwest of Fort Worth and nearly at the geographical center of the state of Texas, Dublin had been an oasis of protection and shade in an unforgiving sea of scrub oaks and native grasslands. It occupied a limestone rise of forested hills that were notable for their clear running creeks and abundance of wild turkey, prairie chicken, and free-ranging buffalo.

The Comanche, Kiowa, Lipan, and Apache tribes who hunted these bleak surrounding lands, undisturbed for centuries before white settlers pushed into the region, were more than a little reluctant to give them up to the newcomers, and thus Dublin's early town records are filled with vivid accounts of deadly skirmishes between uninvited homesteaders and native inhabitants, family massacres, and revenge killings.

As late as the start of the twentieth century, surviving elements of these "pacified" native peoples periodically committed violent raids on Dublin township for horses and cows, and a year seldom passed without the murder of a farmer or disappearance of a town resident caught unaware in some isolated outlying area. "My grandmother used to say this was God's country," remembers a modern resident of Dublin whose family roots burrow back to the town's formation. "He put this nice little Christian town smack in the middle of a country that was meaner than hell. Reckon only He could truly love it."

One popular account of how Dublin got its name holds that it came from the shouted alert to "double in the wagons! Indians a'comin'!" though the abundance of Irish surnames in local graveyards suggests the founding fathers were probably more intent upon honoring their distant homeland when Dublin actually appeared on government land maps around 1860. A less likely if more colorful theory holds that the name derived from the raucous Double Inn Hotel that opened up about the time the railroad arrived to serve the needs of a more prosperous crossroads economy, a notorious roadhouse that specialized in strong drink and cheap beds.

Five years after the Yuma Stagecoach Line made Dublin a regular stop in 1874, the Texas Central Railroad surveyed a line straight through the heart of town and opened a small depot there in 1881, prompting an influx of cattlemen and cotton farmers aiming to seek their fortunes on the edge of a wild new country. One of those who came to town was a young, rawboned Mississippian looking for a new start. William Alexander Hogan had spent a year serving as a blacksmith in a Confederate cavalry unit before taking a bride four years his senior and settling down to try to raise cotton on rented land back in Mississippi. After five years of hard tenant labor that left the Hogans with little or nothing to show for their efforts, William and Cinthia Hogan pulled up stakes and joined the migration to the promised land of west Texas, arriving in Dublin sometimes after 1870 with their four young children: William, Josephine, Martha, and Mary. According to Sunday school records, they joined the First Baptist Church almost immediately upon arriving in town, and William abandoned farming in favor of the trade he'd learned in the Confederate Army.

Whether by chance or design, the opening of a new blacksmith shop on Elm Street, just a block or so from the center of town, was fortuitously timed because the same railroad that brought settlers into the formerly untamed region also brought cattle ranchers and cotton farmers in growing numbers, people who relied heavily on the horse for their livelihoods and transportation needs.

On February 2, 1885, a fifth and final child was born to the Hogans, a solemn dark-eyed boy they called Chester, possibly after the outgoing president of the United States. At an early age, according to early family lore--what little of it managed to pass down the line--Chester Hogan was drawn to the dust and bustle of his father's workplace, often spending his days at the blacksmith shop tending horses and watching customers come and go. He was said to be an unusually sweet-dispositioned child given to periods of prolonged silence.

In 1889 a spur of the larger Fort Worth-Rio Grande Railroad reached Dublin and an opera house opened its ornate doors, featuring dance hall girls and the kind of rowdy frontier melodramas that soon attracted patrons from as far away as Fort Worth and Dallas. One of those who found himself attracted to the town's mix of the Old West and the new ways was Sam Houston Prim, a former bookstore owner who contracted to produce and bottle a carbonated concoction that was all the rage down in Waco, a sweet soda beverage called Dr. Pepper. Sensing an opportunity to get the jump on merchants restricted to peddling the newfangled soda drink from their traditional lunch counters around the Lone Star State, Prim opened his small bottling plant with the greater ambition to make Dr. Pepper available at every general store and grocery purveyor in west Texas. To do so, he hired his brother and a nephew to mix chilled carbonated water and flavored syrup in Hutchinson bottles, which could then be sealed with wire corks and shipped imperishably anywhere there were good roads or rail lines. The idea caught on like a fever, and Prim was soon expanding his operation and looking for extra hands to bottle and ship his soda. In due course, Prim hired the quiet but hardworking youngest son of William Hogan to wash returned bottles, refill and cork them, and crate them up for shipment.

Chester Hogan was believed to be twenty years old and already married the spring he briefly left his father's blacksmith shop to bottle Dr. Pepper, and in a famous photograph that the Dublin Progress newspaper published in 1955--half a century later--the youngest Hogan appears erect and taciturn, with an almost Lincoln-like solemnity and bearing about the eyes, remarkably like the two sons he would father within a decade. Not long after the photograph appeared in print, the newspaper's editor received a pair of politely worded letters from golfer Ben Hogan, the first requesting a "glossy print of this original picture at your earliest possible convenience," the second a short while later expressing the letter writer's deep appreciation for a prompt reply and dispatch of the photograph in question. Neither letter made even passing reference to the fact that the man in the photograph was Ben Hogan's father.

Chester Hogan, in any case, was married to the former Clara Williams, third child of a Dublin cotton buyer who grew up in a rented house on nearby Grafton Street, a short time after he went to work for Sam Prim. Her father, Ben Williams, a prominent member of the Baptist church, was remembered as being a fastidious dresser and a quick-witted man who could instantly work out the most complicated math problems in his head even while simultaneously transacting purchases of bundled bails of raw cotton that were brought from the fields by the wagonload to the Dublin train depot. It was Williams's job to grade and purchase bails of raw cotton fiber, then mark and ship them on for processing to northern clothing and thread manufacturing companies. For his trouble, he collected 10 percent of every consummated purchase.

Cotton was king across much of the American South in those days, and Ben Williams had social ambitions that probably didn't include his pretty, spirited daughter marrying the silent heir of the village smithy shop.

As a Fort Worth reporter snooping around in Ben Hogan's mysterious early life in the late 1950s first discovered--but chose not to reveal--there was apparently no marriage certificate between Chester Hogan and Clara Williams filed anywhere in the courthouse records of Erath or neighboring Comanche County, leading some to surmise that the young couple may simply have eloped or quietly gone off and married in a hurry, owing to an impending arrival. In any case, from family sources it's known that Clara was eighteen in 1908 when she gave birth for the first time to a boy she rather fancifully named Royal Dean. Two years later a daughter was born at home, probably at the young couple's modest wooden frame house on Camden Street. Projecting her ambitions for a more refined life on her first and only female child, Clara named the girl Chester Princess.

Finally, on August 13, 1912, a few days after the Bull Moose Party nominated Theodore Roosevelt for president and advocated a platform promoting women's suffrage and sweeping election reform, Clara Hogan delivered a second son at the new women's infirmary in nearby Stephensville, the county seat. For reasons unclear--possibly having to do with her natural distrust of strangers or the dying western tradition that held all newborns should be properly named at home (it was bad luck to do otherwise)--Mama Hogan chose not to give the baby a formal name until she brought her infant male home to Dublin.

Both Royal Dean and Princess were remembered by Dublin elders as lively babies who seemed to possess their mama's extroverted nature, but the third Hogan issue had both his father's calm and watchful personality and his mother's imposing blue-gray eyes. Clara eventually decided to call him William Ben Hogan, after both his grandfathers, the diligent blacksmith and the enterprising cotton broker, a pretty good choice considering the way young Bennie turned out in life.

Except for his modestly phrased letters of inquiry and gratitude to the Dublin Enterprise, sent and received during the summer of 1955--the year he just missed winning a record fifth National Open and announced his intention to "retire" from full-time professional golf to pursue "other interests"--Ben Hogan rarely acknowledged his blood connection to the rough little pioneer railhead of his birth on the edge of former Indian country. In light of what followed nine years after his birth, it's not too surprising that he flatly refused to ever publicly mention the circumstances that drove the family from the town, and never even spoke of it to the woman he chose to court and marry until his own mother let the secret out many years later.

"One of the first things I learned about our family was that nobody talked about the past or wrote things down unless it was completely necessary, and certainly not that," reflects Jacqueline Hogan Towery, Royal Hogan's only daughter and one of two nieces Ben Hogan came to regard as if they were his own daughters. "For the Hogans, Dublin was essentially the end of the line. And the way they looked at it, if you wrote something down it might later be used against you. So there was no chance of family history ever being written. Growing up, I never heard my grandmother say anything about my grandfather, her late husband. Chester was the man never mentioned in our house. All we knew was that he'd somehow gotten sick and eventually died. And then she'd brought her family to Fort Worth to get on with things, to start a new life."

Before that abrupt and violent partitioning from their birthplace took place, by all accounts the three Hogan children experienced fairly ordinary and even happy childhoods in the quiet oak-shaded streets of Dublin. Once Chester returned to take over his father's blacksmith shop on Elm Street, shoeing horses provided sufficient income to permit Chester and Clara to own a second small rental house, and for many years the family wasn't anywhere nearly as destitute as later accounts of Hogan's early childhood days present them as being. On the contrary, life for the Hogan charges appears to have been something of a rural American idyll, with picnics by Clear Creek and evening suppers at the Baptist church. An early newspaper advertisement for the family business, for example, includes a photograph of the Hogan children bundled together on a pony wagon draped with a Fourth of July parade sign that cheerfully reads: "pappa's a blacksmith. let hogan shoe your horse!"

The oldest boy, Royal Hogan, was remembered as a natural athlete who organized neighborhood teams and pitched a mean sandlot baseball game; Princess, who had her mother's gregarious personality, stern good looks, and no shortage of the Williams charm and ambition, sang at church and even earned a few bit parts in musical productions at the old Dublin Opera Hall. Neighbors from those years who knew the family often remembered that quiet little Bennie Hogan seemed to be his father's boy to the core, a thoughtful lad who was shy but unfailingly polite around adults, a bit of a happy loner who loved to poke around his father's busy blacksmith shop, where he calmed the horses as they waited to be shoed and fed scraps of his lunch to the village dogs that always congregated there on hot summer days. Tellingly, decades later, Ben Hogan's favorite keepsake from this faraway childhood--his most prized family possession--was a small black-and-white photograph that shows him sitting peacefully on his father's lap, astride a chestnut mare. Bennie was maybe a year old at the time, being cradled between his father's belt and the saddle horn, already clutching the reins like a true son of the West. Father and son are both looking away from the camera's lens, as if scanning some unknown horizon, but the spiritual connection between them is unmistakable. Their expressions and profiles are serenely calm, and nearly identical.

As his father had been, young Bennie was a bit undersized for his age, the classic neighborhood runt, and some recalled that he seemed destined to grow up in Royal's shadow, reduced to playing the "pigtail" during sandlot games where Royal was always pitching, the extra boy who chased down errant throws the catcher missed, just waiting for his chance to get invited into the game. For other entertainments, the Hogan children swam in Clear Creek and went to the open-air movie theater just off Dublin's dusty main square on Friday nights, plunking down a nickel for a seat on a hard bench to watch Douglas Fairbanks in The Knickerbocker Buckeroo or Charlie Chaplin's Shoulder Arms. Even then, Bennie Hogan shared his big sister Princess's fascination with the magic of Hollywood movies, in thrall of a world of glamour and fortune that felt about as far away as one could possibly get from the dust and heat of God's country and their father's already dwindling blacksmith trade.

The year 1920 was a watershed year for America in general and for Texas in particular. The "Great War to end all wars" had claimed the lives of five thousand Texans but ended with the signing of the Armistice in 1918. By 1920 the war's end had produced a manufacturing boom and a revolution in goods and services back home that promised to transform the American landscape as never before, beginning and ending with Main Street itself.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"A must-read for any golf fan." —Portland Oregonian

"Dodson... resurrects the flesh-and-blood man from the ashes of apocrypha, providing the most intimate and richly textured portrait of the famous golfer to date." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"Dodson... resurrects the flesh-and-blood man from the ashes of apocrypha, providing the most intimate and richly textured portrait of the famous golfer to date." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Descriere

In this first-ever family-authorized biography, Dodson expertly and emotionally reconstructs Ben Hogan's complicated life, revealing him to be a warm, jovial man whose charitable spirit and sharp business sense enabled him to build the powerful golf equipment company bearing his name to this day.

Premii

- USGA Herbert Warren Wind Winner, 2004