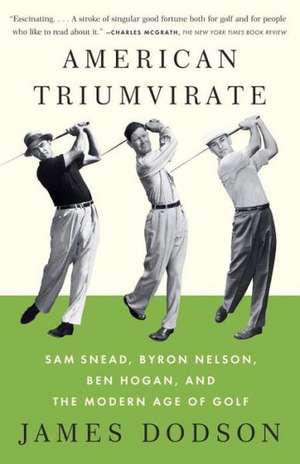

American Triumvirate: Sam Snead, Byron Nelson, Ben Hogan, and the Modern Age of Golf

Autor James Dodsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 feb 2013

During the Depression golf was in crisis. As a spectator sport it was on the verge of extinction. This was the unhappy prospect facing Sam Snead, Byron Nelson, and Ben Hogan ߝtwo dirt-poor boys from Texas and another from Virginia, who had dedicated themselves to the sport. But then lightning struck, and from the late thirties into the fifties these three men were so thoroughly dominant that they transformed both how the game was played and how society regarded it. Paving the way for the subsequent popularity of players from Arnold Palmer to Tiger Woods, they were, and will always remain, a triumvirate for the ages.

Preț: 119.33 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.84€ • 24.82$ • 19.20£

22.84€ • 24.82$ • 19.20£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307473554

ISBN-10: 0307473554

Pagini: 378

Ilustrații: 24 PP. B&W

Dimensiuni: 134 x 208 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307473554

Pagini: 378

Ilustrații: 24 PP. B&W

Dimensiuni: 134 x 208 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

James Dodson is the editor of O. Henry and PineStraw magazines and an award-winning writer-in-residence at The Pilot newspaper. He is the author of Ben Hogan’s authorized biography and worked with Arnold Palmer on his, and his other best-selling books include Final Rounds, The Dewsweepers, and A Son of the Game. He wrote a column for Golf Magazine for nearly twenty years, and in 2011 he received the Donald Ross Award from the American Society of Golf Course Architects for his contribution to golf literature. In observance of the 100th anniversary of the births of Hogan, Snead and Nelson, American Triumvirate was adapted into a tribute documentary that aired on Golf Channel in September 2012, with a script by the author.

Extras

Excerpted from the hardcover edition

1. Year of Wonders

At seven o’clock on a cool Indian summer Saturday evening, eager to catch a glimpse of the future, thousands of patrons began filing into venerable Mechanic’s Hall on Huntington Avenue, happy to be among the first to see the wonders of the 1912 Boston Electric Show. “Electric devices unheard of just one year ago are to be exhibited in full operation,” wrote a reporter for The Christian Science Monitor, “inventions which make the fable of Aladdin and his magical lamp seem prosy by comparison.”

Emblematic of the affair, Mechanic’s Hall was ablaze with forty thousand light bulbs, the largest display of incandescent lighting ever mounted; the creation of the Edison Illuminating Company of New Yorks outshone the “Great White Way itself,” the company promised. Owing to the marvels of alternate electrical current, wide-eyed patrons wandered through the vast hall being serenaded by live opera and choir selections amplified by an invention called the microphone (“such a delicate instrument that by its agency the tread of a fly is magnified until it sounds like the clomping of a horse over the loose planks of a country bridge”) and saw inventions designed to transform everything “from the farmyard to Main Street, from the shop floor to the housewife’s kitchen.” They viewed a dairy farm where cows were milked by automated machines, for instance, promising to make the drudgery of hand milking obsolete, and an electric forking machine that could unload two hundred bales of hay from a wagon and stack them in a loft in a matter of minutes rather than hours, reducing the need for hired labor.

There were special motion pictures displaying how the dedicated electrical current would soon transform businesses from accountancy to coal mining; how it would count money in banks and permit a clerk in one location to inquire about a customer’s account balance in a separate building altogether, achieving a response within seconds; how bakers would never need to touch the bread they sold because machines would mechanically mold dough into perfect loaves and bake them by the clock to golden perfection; how lumber mills would use power saws to mill stockpiles of flawless high-grade lumber for the booming furniture and house-building trades in minutes, not hours; how darkened streets would soon be made bright as noon by municipal lighting soon coming to market, “pressing back the cloak of night and greatly reducing the scourge of crime and hoodlum behavior.”

Perhaps the most popular aspect of the revolution on the doorstep, the show’s organizers promised, would be the liberation of the ordinary housewife thanks to special electric appliances that would wash and sanitize dishes, eliminating the need for madam or a domestic to ever touch a single china plate that wasn’t sparkling clean. Ovens would bake cakes and roasts according to an electric clock that would make expert cooking a snap at home. An exciting new commercial “electric refrigerator”—the world’s first, being introduced that year by the General Electric Corporation—promised to make spoiled fruits, vegetables and meats a thing of the past.

“This magical showcase at Mechanic’s Hall fittingly serves as a capstone to a year that has seen one astonishment after another, all aimed at providing more leisure time for Americans to enjoy the bounty of their lives,” declared The Boston Evening Traveler. “Many will look back and perhaps agree there has never been a year quite like it.”

To be sure, it had been a year of human wonders.

Despite jitters about rising Anglo-German tensions over some obscure place called the Balkans in a faraway corner of Europe, most Americans were enjoying an unprecedented sense of prosperity and well-being, the afterglow of a Gilded Age that produced untold wealth for a few but also labor reforms that dramatically expanded the reach and power of a newly emerging middle class. Earlier that year in Detroit, Henry Ford revealed plans for the first moving assembly line, a concept that would revolutionize the manufacture of reasonably priced consumer goods and herald the arrival of a reliable automobile that almost any American with a good job could afford to own. Banks responded by offering new credit terms to qualified customers based on easy time-payment plans.

In January, New Mexico became the forty-seventh state; less than a month later, Arizona joined the union, too. The world’s first “flying boat” took flight, Frederick Law made the first successful parachute jump from the Statue of Liberty, and a few weeks later another daredevil upped the ante by leaping from an airplane. For the first time ever that year, the 100 mph air speed barrier was broken and a transcontinental passenger flight was completed.

Daily newspapers, experiencing a surge in circulation, couldn’t cover the emerging wonders of human achievement fast enough, including Amundsen’s successful race to the South Pole and Scott’s unfortunate demise, the establishment of China as a republic, and the exciting launch of the Titanic, said to be the most lavish and technically advanced ocean liner in history, all but unsinkable according to widely distributed reports.

With more time and disposable income on their hands, Americans read with interest about Mrs. Taft planting the first cherry trees along the Potomac in Washington, the formation of the Girl Scouts in Savannah, Georgia, and Columbia University’s creation of something called the Pulitzer Prize. A record number of public libraries and more than one hundred movie theaters opened in 1912 alone, bringing the magic of the first Keystone Kops movie to small towns across the nation. That summer children were either playing a new craze called “marbles” or enjoying a fruit-flavored summer candy called “Life Savers” that was guaranteed not to melt in summer heat.

Professional sports were another lifesaver, particularly baseball. At least a half dozen records fell that year—for triples and stolen bases, attendance and consecutive wins. After multiple suspensions for fighting with fans and opponents, Ty Cobb publicly hinted at an early retirement from the game. After 511 wins, Cy Young actually did retire. Several state-of-the-art ballparks opened that year, including Tiger Stadium in Detroit and Boston’s Fenway Park, where a sold-out crowd of 27,000 fans got to see the hometown Red Sox beat the New York Highlanders (soon to be the Yankees) 7ߝ6 in a marathon season opener that lasted eleven innings.

Ironically, Fenway Park was knocked off the front pages of Boston’s newspapers by news that the Titanic, on its maiden voyage, had struck an iceberg and sunk off the coast of Newfoundland, killing 1,500 passengers and crew.

In 1912, golf in this country was barely two decades old, played by roughly two million Americans on about fifteen hundred courses of widely varying quality in all forty-eight states. For the vast majority, it was simply a recreational pursuit with unmistakably patrician overtones, conveyed to these shores by a wave of immigrant Scottish professionals who accurately perceived that a comfortable living could be made promoting the game of their ancestors. Until fairly recently, Americans had been more comfortable as spectators than as participants at sporting events. But the surprising popularity of golf, particularly among the middle and merchant classes, suggested that a cultural sea change might be under way. In addition to the private clubs where it first took root, virtually every municipality of any size now offered a rudimentary golf course, most of which were crowded on any given weekend in fair weather months with men and women eager to learn about the game.

More telling, perhaps, at least eight different companies were now manufacturing hickory-shafted golf clubs, and a half a dozen more producing a newly introduced rubber-cored golf ball. Meanwhile, such seasonal resorts at places like Poland Spring in the highlands of Maine, Saratoga in New York, and Pinehurst down in the Carolina Sandhills—which was in the process of adding its third golf course under the guidance of Scotsman Donald Ross—helped establish the game as both a wholesome activity for the new leisure class and a serious competitive sport for any swell who had the gumption to try to excel at it.

All of this was the result of one man’s international celebrity.

A dozen years earlier, in February of 1900, when Harry Vardon came strolling down the ship’s gangway to begin his heavily publicized exhibition tour of America, he was greeted like a visiting head of state by a crush of reporters and photographers eager to learn everything they could about England’s most acclaimed sportsman, an elegant, gracious man who’d been nicknamed “The Greyhound” because he typically bounded ahead of competitors in tournaments and rarely yielded ground. His only rival, every British schoolboy knew, was John Henry Taylor, a quiet, dignified man from the windswept links at North Devon Golf Club, more popularly known as Westward Ho! J.H., as he was called by his friend Harry and other intimates, had won the British Open Championship twice, in 1894 and again the following year.

Vardon, the son of a manual laborer from the Isle of Jersey, began his working life as a gardener but quickly evolved into a club professional, employed at Ganton Golf Club in Lincolnshire. He was twenty-nine years old when he arrived in America, having already claimed three Open Championships with a slightly upright golf swing that was so deceptively smooth and refined that his irons and fairway woods rarely left more than a modest scuff on the turf. Opponents claimed Harry’s tee shots were so maddeningly precise in tournament play they often wound up in the same spot where he had hardly left a mark from the day before.

His ostensible reason for visiting America was to play in the fledgling United States Open and conduct an extensive tour of public exhibitions to promote the Vardon Flier, a so-called gutty golf ball manufactured by the A. G. Spalding Company of Chickopee, Massachusetts. Mr. Spalding had a private course on his estate, and had agreed to pay Vardon a princely fee of $2,000 for ten months of exhibitions, on top of any appearance fees he could generate during the tour. Back home, J. H. Taylor had also confided to friends his intention to give chase to his friend the Greyhound and all comers at the National Championship of America, conducted that year at Chicago Golf Club in Wheaton, Illinois.

Whoever actually won the affair—accomplished thus far only by five Scottish immigrants, each gainfully employed as a club professional in America—would undoubtedly result in an avalanche of favorable press for the ball he used, for golf was not only increasingly shaped by both the men who played and those who knew that money could be made catering to the growing number of adherents.

For nearly half a century, the venerable gutta-percha ball had reigned supreme, dating from a famous dispute between golf’s two most celebrated founding fathers. In the 1840s, Allan Robertson, a short, friendly Scot, was the first true professional and widely regarded as the finest player of his time; the son of a senior caddie at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club, he operated a thriving business making clubs and traditional feathery balls just off Links Road in St. Andrews. Although a new feathery ball could be driven great distances, the ball—made from a top-hat-ful of goose feathers compressed into a stitched leather orb—was fragile and subject to either losing its shape or breaking apart after only slight use. The balls were also expensive to produce, costing about half a crown apiece, thus attractive to the better-heeled classes.

Still, records show that Robertson and his shop assistants turned out 2,456 featheries in 1844 alone. Twenty-three-year-old Tom Morris—son of a local weaver, he’d taken to the game by batting a wine cork around the Auld Grey Toon, as locals called St. Andrews—had worked for Robertson since the age of fourteen, apprenticing in his shop for five years before becoming a journeyman salesman. By 1845 Morris was not only his junior partner but also nearly his equal on the links. The two steadfastly avoided playing a head-to-head match but frequently teamed up in big-money challenge matches against other leading professionals including Willie Park Sr. and the Dunns of Musselburgh. A famous match against Willie and Jamie Dunn with 400 pounds sterling at stake helped seal their reputations. Four holes down with eight to play, Morris and Robertson closed the gap and won on the final hole, earning the sobriquet “The Invincibles” among the golfing laity. News of the victory didn’t hurt their business one bit.

In April of 1848, however, a man named Tom Peters stepped into Robertson’s shop to show him a new kind of golf ball he’d acquired from a local divinity student named Robert Patterson. It was hard and perfectly round, made from the hardened milk sap of the Palaquium gutta tree of Malaysia. Three years before, Robert’s father, Rev. Robert Adams Patterson, had discovered strips of this malleable substance used to pack a statue of the Hindu god Vishnu sent by a friend from the Far East. Being naturally thrifty, he boiled the material down and used sheets of it to resole his family’s shoes, but his enterprising son saw a potentially better use for the waterproof material. Young Robert used the softened gutta to make perfectly round golf balls he promptly went out and played with on the links. Then, after years of tinkering with the formula, his brother came up with a ball that flew farther and straighter and kept its shape much longer than the traditional featheries. Moreover, the newly patented “gutty” ball could be made and sold at a fraction of the cost.

Peters declared that the day of the feathery ball was over, and Robertson—who’d introduced the use of iron clubs in competition, heads of earlier sets having been made of apple wood—agreed to give the new ball a try. He woefully hooked his first shot, perhaps intentionally, and reportedly dismissed the gutty ball with undisguised contempt.

The problem arose when mild and mannerly Tom Morris teamed with a member of the R&A in a match in the summer of 1851, and used these controversial new balls. When he heard of this betrayal, an outraged Robertson confronted his longtime partner and fired him on the spot. A short time later, Morris was hired by the Prestwick Golf Club to lay out and maintain its new course and serve as club professional.

Old Tom, as he was soon to be called, started his own equipment business, making clubs and balls and selling both featheries and gutties. He would also be instrumental in mounting the first Open Championship at Prestwick in 1860, a year after his fiery mentor, Robertson, had passed away, and himself captured the title four times from 1861 to 1867. By that time, the gutty was the preferred ball of better players, including his son, Young Tom Morris, who won his first of four consecutive Opens in 1868, a mere stripling of twenty who shattered scoring records and brought the game to new levels of brilliance and popular notice before his premature death following the sudden loss of his young wife and infant son while he was away playing a match.

The reign of Allan Robertson and Tom Morris père et fils was over, but the durable gutty prevailed for another many years in competition.

When J. H. Taylor, the current British Open champion, opened his locker at the Chicago Golf Club in the early October of 1900, he supposedly found a complimentary tin of a new rubber-cored ball that was causing a major row on both sides of the Atlantic, the gift of a bicycle manufacturer named Coburn Haskell.

Haskell, a mediocre but passionate golfer, had a brainstorm one warm afternoon while sitting on the porch of the Cleveland Country Club, chatting with the head professional. As he squeezed a handful of rubber bands, the story goes, a revolutionary idea took shape. For all its popularity, the gutta-percha ball had its flaws—principally a certain deadness if it wasn’t struck perfectly. Haskell contacted a friend named Bertram Work at the B. F. Goodrich plant in Akron, twenty miles south of Cleveland, and explained his idea of wrapping bands of rubber tightly around a solid rubber core, then covering it all with gutta-percha, thereby producing a much livelier golf ball. Work signed on and the two struck a deal to evenly split any proceeds from their innovation, which they patented in 1898. When the first “Haskell” was put into play a short time later, its superiority became immediately apparent.

The new ball flew twenty yards beyond the old gutty. Traditionalists both here and abroad quickly inveighed sharply against the new American golf ball—including Harry Vardon himself, initially dismissing them as “Bounding Billies” because they allegedly were difficult to control around the greens. But the swift acceptance by players forever in search of greater distance and any competitive edge guaranteed another major turning point in the game.

This happened just as three players were becoming dominant.

1. Year of Wonders

At seven o’clock on a cool Indian summer Saturday evening, eager to catch a glimpse of the future, thousands of patrons began filing into venerable Mechanic’s Hall on Huntington Avenue, happy to be among the first to see the wonders of the 1912 Boston Electric Show. “Electric devices unheard of just one year ago are to be exhibited in full operation,” wrote a reporter for The Christian Science Monitor, “inventions which make the fable of Aladdin and his magical lamp seem prosy by comparison.”

Emblematic of the affair, Mechanic’s Hall was ablaze with forty thousand light bulbs, the largest display of incandescent lighting ever mounted; the creation of the Edison Illuminating Company of New Yorks outshone the “Great White Way itself,” the company promised. Owing to the marvels of alternate electrical current, wide-eyed patrons wandered through the vast hall being serenaded by live opera and choir selections amplified by an invention called the microphone (“such a delicate instrument that by its agency the tread of a fly is magnified until it sounds like the clomping of a horse over the loose planks of a country bridge”) and saw inventions designed to transform everything “from the farmyard to Main Street, from the shop floor to the housewife’s kitchen.” They viewed a dairy farm where cows were milked by automated machines, for instance, promising to make the drudgery of hand milking obsolete, and an electric forking machine that could unload two hundred bales of hay from a wagon and stack them in a loft in a matter of minutes rather than hours, reducing the need for hired labor.

There were special motion pictures displaying how the dedicated electrical current would soon transform businesses from accountancy to coal mining; how it would count money in banks and permit a clerk in one location to inquire about a customer’s account balance in a separate building altogether, achieving a response within seconds; how bakers would never need to touch the bread they sold because machines would mechanically mold dough into perfect loaves and bake them by the clock to golden perfection; how lumber mills would use power saws to mill stockpiles of flawless high-grade lumber for the booming furniture and house-building trades in minutes, not hours; how darkened streets would soon be made bright as noon by municipal lighting soon coming to market, “pressing back the cloak of night and greatly reducing the scourge of crime and hoodlum behavior.”

Perhaps the most popular aspect of the revolution on the doorstep, the show’s organizers promised, would be the liberation of the ordinary housewife thanks to special electric appliances that would wash and sanitize dishes, eliminating the need for madam or a domestic to ever touch a single china plate that wasn’t sparkling clean. Ovens would bake cakes and roasts according to an electric clock that would make expert cooking a snap at home. An exciting new commercial “electric refrigerator”—the world’s first, being introduced that year by the General Electric Corporation—promised to make spoiled fruits, vegetables and meats a thing of the past.

“This magical showcase at Mechanic’s Hall fittingly serves as a capstone to a year that has seen one astonishment after another, all aimed at providing more leisure time for Americans to enjoy the bounty of their lives,” declared The Boston Evening Traveler. “Many will look back and perhaps agree there has never been a year quite like it.”

To be sure, it had been a year of human wonders.

Despite jitters about rising Anglo-German tensions over some obscure place called the Balkans in a faraway corner of Europe, most Americans were enjoying an unprecedented sense of prosperity and well-being, the afterglow of a Gilded Age that produced untold wealth for a few but also labor reforms that dramatically expanded the reach and power of a newly emerging middle class. Earlier that year in Detroit, Henry Ford revealed plans for the first moving assembly line, a concept that would revolutionize the manufacture of reasonably priced consumer goods and herald the arrival of a reliable automobile that almost any American with a good job could afford to own. Banks responded by offering new credit terms to qualified customers based on easy time-payment plans.

In January, New Mexico became the forty-seventh state; less than a month later, Arizona joined the union, too. The world’s first “flying boat” took flight, Frederick Law made the first successful parachute jump from the Statue of Liberty, and a few weeks later another daredevil upped the ante by leaping from an airplane. For the first time ever that year, the 100 mph air speed barrier was broken and a transcontinental passenger flight was completed.

Daily newspapers, experiencing a surge in circulation, couldn’t cover the emerging wonders of human achievement fast enough, including Amundsen’s successful race to the South Pole and Scott’s unfortunate demise, the establishment of China as a republic, and the exciting launch of the Titanic, said to be the most lavish and technically advanced ocean liner in history, all but unsinkable according to widely distributed reports.

With more time and disposable income on their hands, Americans read with interest about Mrs. Taft planting the first cherry trees along the Potomac in Washington, the formation of the Girl Scouts in Savannah, Georgia, and Columbia University’s creation of something called the Pulitzer Prize. A record number of public libraries and more than one hundred movie theaters opened in 1912 alone, bringing the magic of the first Keystone Kops movie to small towns across the nation. That summer children were either playing a new craze called “marbles” or enjoying a fruit-flavored summer candy called “Life Savers” that was guaranteed not to melt in summer heat.

Professional sports were another lifesaver, particularly baseball. At least a half dozen records fell that year—for triples and stolen bases, attendance and consecutive wins. After multiple suspensions for fighting with fans and opponents, Ty Cobb publicly hinted at an early retirement from the game. After 511 wins, Cy Young actually did retire. Several state-of-the-art ballparks opened that year, including Tiger Stadium in Detroit and Boston’s Fenway Park, where a sold-out crowd of 27,000 fans got to see the hometown Red Sox beat the New York Highlanders (soon to be the Yankees) 7ߝ6 in a marathon season opener that lasted eleven innings.

Ironically, Fenway Park was knocked off the front pages of Boston’s newspapers by news that the Titanic, on its maiden voyage, had struck an iceberg and sunk off the coast of Newfoundland, killing 1,500 passengers and crew.

In 1912, golf in this country was barely two decades old, played by roughly two million Americans on about fifteen hundred courses of widely varying quality in all forty-eight states. For the vast majority, it was simply a recreational pursuit with unmistakably patrician overtones, conveyed to these shores by a wave of immigrant Scottish professionals who accurately perceived that a comfortable living could be made promoting the game of their ancestors. Until fairly recently, Americans had been more comfortable as spectators than as participants at sporting events. But the surprising popularity of golf, particularly among the middle and merchant classes, suggested that a cultural sea change might be under way. In addition to the private clubs where it first took root, virtually every municipality of any size now offered a rudimentary golf course, most of which were crowded on any given weekend in fair weather months with men and women eager to learn about the game.

More telling, perhaps, at least eight different companies were now manufacturing hickory-shafted golf clubs, and a half a dozen more producing a newly introduced rubber-cored golf ball. Meanwhile, such seasonal resorts at places like Poland Spring in the highlands of Maine, Saratoga in New York, and Pinehurst down in the Carolina Sandhills—which was in the process of adding its third golf course under the guidance of Scotsman Donald Ross—helped establish the game as both a wholesome activity for the new leisure class and a serious competitive sport for any swell who had the gumption to try to excel at it.

All of this was the result of one man’s international celebrity.

A dozen years earlier, in February of 1900, when Harry Vardon came strolling down the ship’s gangway to begin his heavily publicized exhibition tour of America, he was greeted like a visiting head of state by a crush of reporters and photographers eager to learn everything they could about England’s most acclaimed sportsman, an elegant, gracious man who’d been nicknamed “The Greyhound” because he typically bounded ahead of competitors in tournaments and rarely yielded ground. His only rival, every British schoolboy knew, was John Henry Taylor, a quiet, dignified man from the windswept links at North Devon Golf Club, more popularly known as Westward Ho! J.H., as he was called by his friend Harry and other intimates, had won the British Open Championship twice, in 1894 and again the following year.

Vardon, the son of a manual laborer from the Isle of Jersey, began his working life as a gardener but quickly evolved into a club professional, employed at Ganton Golf Club in Lincolnshire. He was twenty-nine years old when he arrived in America, having already claimed three Open Championships with a slightly upright golf swing that was so deceptively smooth and refined that his irons and fairway woods rarely left more than a modest scuff on the turf. Opponents claimed Harry’s tee shots were so maddeningly precise in tournament play they often wound up in the same spot where he had hardly left a mark from the day before.

His ostensible reason for visiting America was to play in the fledgling United States Open and conduct an extensive tour of public exhibitions to promote the Vardon Flier, a so-called gutty golf ball manufactured by the A. G. Spalding Company of Chickopee, Massachusetts. Mr. Spalding had a private course on his estate, and had agreed to pay Vardon a princely fee of $2,000 for ten months of exhibitions, on top of any appearance fees he could generate during the tour. Back home, J. H. Taylor had also confided to friends his intention to give chase to his friend the Greyhound and all comers at the National Championship of America, conducted that year at Chicago Golf Club in Wheaton, Illinois.

Whoever actually won the affair—accomplished thus far only by five Scottish immigrants, each gainfully employed as a club professional in America—would undoubtedly result in an avalanche of favorable press for the ball he used, for golf was not only increasingly shaped by both the men who played and those who knew that money could be made catering to the growing number of adherents.

For nearly half a century, the venerable gutta-percha ball had reigned supreme, dating from a famous dispute between golf’s two most celebrated founding fathers. In the 1840s, Allan Robertson, a short, friendly Scot, was the first true professional and widely regarded as the finest player of his time; the son of a senior caddie at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club, he operated a thriving business making clubs and traditional feathery balls just off Links Road in St. Andrews. Although a new feathery ball could be driven great distances, the ball—made from a top-hat-ful of goose feathers compressed into a stitched leather orb—was fragile and subject to either losing its shape or breaking apart after only slight use. The balls were also expensive to produce, costing about half a crown apiece, thus attractive to the better-heeled classes.

Still, records show that Robertson and his shop assistants turned out 2,456 featheries in 1844 alone. Twenty-three-year-old Tom Morris—son of a local weaver, he’d taken to the game by batting a wine cork around the Auld Grey Toon, as locals called St. Andrews—had worked for Robertson since the age of fourteen, apprenticing in his shop for five years before becoming a journeyman salesman. By 1845 Morris was not only his junior partner but also nearly his equal on the links. The two steadfastly avoided playing a head-to-head match but frequently teamed up in big-money challenge matches against other leading professionals including Willie Park Sr. and the Dunns of Musselburgh. A famous match against Willie and Jamie Dunn with 400 pounds sterling at stake helped seal their reputations. Four holes down with eight to play, Morris and Robertson closed the gap and won on the final hole, earning the sobriquet “The Invincibles” among the golfing laity. News of the victory didn’t hurt their business one bit.

In April of 1848, however, a man named Tom Peters stepped into Robertson’s shop to show him a new kind of golf ball he’d acquired from a local divinity student named Robert Patterson. It was hard and perfectly round, made from the hardened milk sap of the Palaquium gutta tree of Malaysia. Three years before, Robert’s father, Rev. Robert Adams Patterson, had discovered strips of this malleable substance used to pack a statue of the Hindu god Vishnu sent by a friend from the Far East. Being naturally thrifty, he boiled the material down and used sheets of it to resole his family’s shoes, but his enterprising son saw a potentially better use for the waterproof material. Young Robert used the softened gutta to make perfectly round golf balls he promptly went out and played with on the links. Then, after years of tinkering with the formula, his brother came up with a ball that flew farther and straighter and kept its shape much longer than the traditional featheries. Moreover, the newly patented “gutty” ball could be made and sold at a fraction of the cost.

Peters declared that the day of the feathery ball was over, and Robertson—who’d introduced the use of iron clubs in competition, heads of earlier sets having been made of apple wood—agreed to give the new ball a try. He woefully hooked his first shot, perhaps intentionally, and reportedly dismissed the gutty ball with undisguised contempt.

The problem arose when mild and mannerly Tom Morris teamed with a member of the R&A in a match in the summer of 1851, and used these controversial new balls. When he heard of this betrayal, an outraged Robertson confronted his longtime partner and fired him on the spot. A short time later, Morris was hired by the Prestwick Golf Club to lay out and maintain its new course and serve as club professional.

Old Tom, as he was soon to be called, started his own equipment business, making clubs and balls and selling both featheries and gutties. He would also be instrumental in mounting the first Open Championship at Prestwick in 1860, a year after his fiery mentor, Robertson, had passed away, and himself captured the title four times from 1861 to 1867. By that time, the gutty was the preferred ball of better players, including his son, Young Tom Morris, who won his first of four consecutive Opens in 1868, a mere stripling of twenty who shattered scoring records and brought the game to new levels of brilliance and popular notice before his premature death following the sudden loss of his young wife and infant son while he was away playing a match.

The reign of Allan Robertson and Tom Morris père et fils was over, but the durable gutty prevailed for another many years in competition.

When J. H. Taylor, the current British Open champion, opened his locker at the Chicago Golf Club in the early October of 1900, he supposedly found a complimentary tin of a new rubber-cored ball that was causing a major row on both sides of the Atlantic, the gift of a bicycle manufacturer named Coburn Haskell.

Haskell, a mediocre but passionate golfer, had a brainstorm one warm afternoon while sitting on the porch of the Cleveland Country Club, chatting with the head professional. As he squeezed a handful of rubber bands, the story goes, a revolutionary idea took shape. For all its popularity, the gutta-percha ball had its flaws—principally a certain deadness if it wasn’t struck perfectly. Haskell contacted a friend named Bertram Work at the B. F. Goodrich plant in Akron, twenty miles south of Cleveland, and explained his idea of wrapping bands of rubber tightly around a solid rubber core, then covering it all with gutta-percha, thereby producing a much livelier golf ball. Work signed on and the two struck a deal to evenly split any proceeds from their innovation, which they patented in 1898. When the first “Haskell” was put into play a short time later, its superiority became immediately apparent.

The new ball flew twenty yards beyond the old gutty. Traditionalists both here and abroad quickly inveighed sharply against the new American golf ball—including Harry Vardon himself, initially dismissing them as “Bounding Billies” because they allegedly were difficult to control around the greens. But the swift acceptance by players forever in search of greater distance and any competitive edge guaranteed another major turning point in the game.

This happened just as three players were becoming dominant.

Recenzii

"Evokes an era when golf was more vivid and less corporate....Dodson manages to reanimate his chosen three. His book makes a convincing case that Snead, Nelson and Hogan really did usher in the modern era of golf—because of the quality of their play and the dramatic nature of their rivalry—and it's also a fascinating biographical account of three gifted, unusual men....That all three should come along at the same time and that their lives should interweave so intricately—one or another of them was always on top of the leader board, it seems—is almost uncanny, a stroke of singular good fortune both for golf and for people who like to read about it." —Charles McGrath, The New York Times Book Review

“The research is thorough and meticulous. The writing is superb… If you love golf, this book should be on your shelf.”—The Tampa Tribune

“Ben Hogan, Sam Snead and Byron Nelson will always be long remembered as giants of the game. Jim's depiction of them magnifies the brilliance of the three, who strangely enough we all born in the year 1912. What a year!” —Ben Crenshaw

“I read it at night, and saw Hogan, Snead and Nelson in my dreams. American Triumvirate is populated by giants, roaming the country in big American-made cars in search of greatness. I'm only sorry Herb Wind isn't around to enjoy it. Jim Dodson has stepped right into the dean's old shoes.” —Michael Bamberger

"James Dodson brings his formidable skills as a raconteur and historian to this rich and sweeping narrative that will engage and move you. His breezy tone made me feel I was with him as he chatted with Hogan, Nelson, and Snead. American Triumvirate is a major contribution to golf’s literature. To read it is to appreciate the power of storytelling in the hands of a master, and what a cast of characters! This singular chronicler of the game—its people, its culture, its tapestry—has done it again." —Lorne Rubenstein, author of Moe and Me: Encounters with Moe Norman, Golf's Mysterious Genius

"Golf is enriched by its history. Thankfully we have writers like Jim Dodson, who with his great love of the game and exceptional writing ability allows the reader to experience the golfing life of three of the game's greatest players as they bring awareness of the professional game to the level we know today." —Barney Adams, founder and chairman, Adams Golf

“It’s always a pleasure to welcome a new book from James Dodson…without doubt one of the best golf writers….But in American Triumvirate, he has almost outdone himself. Filled to the brim with biographical tidbits, insightful golf history and loving portraits of these golfing musketeers in the early years of professional golf history, Dodson’s book captures it all in a readable and exciting narrative. He seems to have interviewed everyone who knew them, and the stories and anecdotes make us feel like we’re right there watching their near perfect golf swings over and over again.” ߝTom Lavoie, Shelf Awareness

“The research is thorough and meticulous. The writing is superb… If you love golf, this book should be on your shelf.”—The Tampa Tribune

“Ben Hogan, Sam Snead and Byron Nelson will always be long remembered as giants of the game. Jim's depiction of them magnifies the brilliance of the three, who strangely enough we all born in the year 1912. What a year!” —Ben Crenshaw

“I read it at night, and saw Hogan, Snead and Nelson in my dreams. American Triumvirate is populated by giants, roaming the country in big American-made cars in search of greatness. I'm only sorry Herb Wind isn't around to enjoy it. Jim Dodson has stepped right into the dean's old shoes.” —Michael Bamberger

"James Dodson brings his formidable skills as a raconteur and historian to this rich and sweeping narrative that will engage and move you. His breezy tone made me feel I was with him as he chatted with Hogan, Nelson, and Snead. American Triumvirate is a major contribution to golf’s literature. To read it is to appreciate the power of storytelling in the hands of a master, and what a cast of characters! This singular chronicler of the game—its people, its culture, its tapestry—has done it again." —Lorne Rubenstein, author of Moe and Me: Encounters with Moe Norman, Golf's Mysterious Genius

"Golf is enriched by its history. Thankfully we have writers like Jim Dodson, who with his great love of the game and exceptional writing ability allows the reader to experience the golfing life of three of the game's greatest players as they bring awareness of the professional game to the level we know today." —Barney Adams, founder and chairman, Adams Golf

“It’s always a pleasure to welcome a new book from James Dodson…without doubt one of the best golf writers….But in American Triumvirate, he has almost outdone himself. Filled to the brim with biographical tidbits, insightful golf history and loving portraits of these golfing musketeers in the early years of professional golf history, Dodson’s book captures it all in a readable and exciting narrative. He seems to have interviewed everyone who knew them, and the stories and anecdotes make us feel like we’re right there watching their near perfect golf swings over and over again.” ߝTom Lavoie, Shelf Awareness