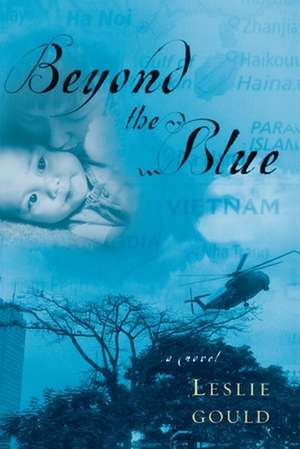

Beyond the Blue

Autor Leslie Goulden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2005

In 1975, an American girl named Genevieve loses her mother when a plane full of orphans crashes in war-ravaged Vietnam. Miles away in the countryside, seven-year-old Lan, a Vietnamese girl, is forced out of her family home by her own brother who has joined the Viet Cong. Worlds apart, these two girls come into womanhood struggling to recover a sense of family–until their journeys suddenly converge.

Lan has grown up in the harsh realities of post-war Vietnam, but she yearns for a better life for her children. Meanwhile, Genevieve marries and, faced with infertility, decides to adopt a child from the country her own mother loved so deeply. But the uncertainty and risk of international adoption threatens to overwhelm both women before their hearts and their families can be healed.

Beyond the Blue is the story of enormous losses, unthinkable choices, and the transforming power of God's love for the children of the world.

Preț: 130.23 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 195

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.92€ • 27.06$ • 20.93£

24.92€ • 27.06$ • 20.93£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781578568222

ISBN-10: 1578568226

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 141 x 211 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

ISBN-10: 1578568226

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 141 x 211 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

Notă biografică

Leslie Gould is the author of Garden of Dreams. She works as an editor and writer in Portland, Oregon where she lives with her husband and four children.

Extras

Chapter 1

Gen sat cross-legged on her bed, clenching her fist around the figurine of the Vietnamese girl, digging her fingernails into her palm. Tomorrow her mother would leave for Vietnam. Gen closed her eyes.

Bombs exploded. Jungles burned. The Viet Cong marched toward Saigon. Nhat cried–all alone–in the orphanage.

Her eyes flew open.

She hadn’t been afraid when her mother traveled to the country a year ago. But now Gen was older; now she was nine; now she knew to be frightened.

Where was Mom? Her mother tucked her into bed every night. What was taking her so long?

Gen opened her hand. The figurine’s dark eyes shone above her tiny nose and lifelike smile; carved braids framed her face. She wore a red tunic and pants and held a miniature wooden doll.

“Time for bed!” Mom hurried into the room.

Mama. Gen squeezed her hand shut again, completely covering the carving.

Her mother sat next to Gen and pulled her close. “You’re going to be the best big sister ever.”

The red fluid in Gen’s lava lamp bubbled and cast a glow over her mom’s face. She was going to Vietnam to bring Nhat home; Gen would finally be a sister.

Her mom smoothed Gen’s dark hair back from her forehead. Her touch was gentle. “Are you worried about anything?”

Gen bit her lower lip and reached for her mother’s hand, holding it tight.

“About my leaving? About Nhat coming home to live with us?” Her mom leaned her cheek against the top of Gen’s head.

Gen snuggled closer. They had been waiting all year for the paperwork to be approved so they could adopt Nhat. She pictured her new little brother holding a bowl of rice, his only meal for the day.

“Mom?”

“What, sweetheart?”

“Does Nhat use chopsticks?”

Her mom smiled. “I don’t think so. He’s only two.”

Photos of Nhat hung on the refrigerator. He was only a year old when the pictures were taken; he was Amerasian with light skin and wavy hair, and he peered at Mom with adoring eyes and a big smile. In one picture, his hands were entwined in her long, dark hair.

“Will you teach him to use chopsticks?”

Her mother’s cheek still rested on Gen’s head. “Yes.”

“And me?”

“And you, Genni.” Genevieve was her given name. Mama was the only one who called her Genni.

Gen slowly opened her hand. The carving was part of a family of place-card holders that her mother bought last year in the open-air market in Saigon. “When will we use these?” Gen ran her finger along the slit that would hold a card in the girl’s back.

“When we have special dinners. Birthdays and holidays.” Her mom laughed a little. “You’ll see. I’ll cook more than Hamburger Helper when I get home. Things will calm down. I’ll spend all my time taking care of you and Nhat.”

“Tell me about Vietnam.” Gen settled her head onto her pillow and stretched out her legs, holding the girl in her open palm. Her mother had lived in Vietnam in 1961, when she was twenty-one, after graduating from nurses’ training. Gen never tired of hearing about her adventures.

“It was the most amazing year of my life.” Her mother stroked Gen’s hair as she spoke. “I lived in a hut with a thatched roof on a mission compound. I picked mangoes, coconuts, and bananas off the trees outside my door. I ate pho, noodle soup, for breakfast. Geckos scampered up the walls of my room and kept me company through the muggy nights. I made friends with a Vietnamese nurse named Kim, whom I love like a sister. I took care of people with leprosy who were missing fingers and toes, noses and ears.”

“Why didn’t you stay in Vietnam?”

“A doctor, a missionary, and a nurse were captured by the Viet Cong when I was home on furlough. My mission organization didn’t think I should return. Then I married your father. Then we had you.” Her mother smiled. Gen’s dad was eleven years older than her mom, but his age didn’t make him seem old, it made her mother seem young. They had met when her mom spoke at his church. Gen closed her hand over the figurine.

Mom put her hand over Gen’s and squeezed. “But I could never stop thinking about Vietnam; it was in my blood. That’s why I raised money and collected supplies for the orphans and hospitals. That’s why I went to Vietnam last year to work in the orphanage and help other people adopt. That’s why we’re adopting Nhat.”

“I want to go with you.” Gen reached for her mother’s hand. She wanted to go even though she would be afraid. She didn’t want her mother to go alone.

“I know.” Gen’s mom squeezed her fingers. “It’s too dangerous right now. Maybe we can go together someday.” She let go of Gen’s hand. “Try to keep your room clean while I’m gone. You know how much it bothers Daddy when it’s messy.”

Gen nodded.

“And be nice to Aunt Marie. She loves you. I know she can be harsh, but remember she’s hurting. She means well.”

Gen nodded again. Aunt Marie was her father’s sister; she would stay with Gen after school while Mom was gone. Her husband had died six months before, and sometimes it seemed that Aunt Marie was angry at everybody because of it. She criticized Gen’s mother’s housekeeping and cooking, Gen’s schoolwork and hair. Nothing felt right when Aunt Marie was around.

“Sally,” Gen’s father called to her mother from the hallway, “you still have to finish packing, and we have to get up early to take you to the airport.”

“G’night, sweetheart.” Gen’s mom leaned toward her. “Always remember how much I love you. Remember to trust God; that’s how you can show your faith. Remember that all things work together for good.” Her mother unclasped the gold chain of the jade cross that she wore and fastened it around Gen’s neck, kissing her forehead.

“I want you to wear this until I get back.” It was the only jewelry her mother ever wore besides her plain gold wedding band. Gen set aside the figurine and fingered the smooth, cool cross.

Her mom pulled her close and kissed her forehead. Gen breathed in her mother’s lilac scent. She touched the green stone again as her mother hugged her tight.

Before she fell asleep, Gen padded down the hall to the bathroom. As she passed her parents’ bedroom, she overheard them talking. Her father’s voice was deep and serious. “Sally, it’s a war zone over there.”

“We’ve waited long enough. If I don’t go now, we may never get Nhat out. What will happen to him?”

“Then I should go.” Her dad sounded worried.

Gen took a step closer to the door. Daddy wants to go to Vietnam? A suitcase lay open on the bed. A stack of disposable diapers leaned against it.

“No, Marshall, it will be much easier for me.”

Her father sat down on the edge of the bed. “I want this to be over. I want you to stop caring so much. We can continue to support the missionaries there, but I want you here with us. I don’t want you going back.”

“I doubt that there will be missionaries to support in Vietnam after this, not with the Viet Cong marching toward Saigon.” Gen’s mother picked up the diapers and wedged them into the suitcase. “The Communists will kick them out. There won’t be much I can do after this either. It’s my last chance.”

Her father put his head in his hands. Her mother turned toward the door. Gen ducked around the corner and into the bathroom.

“Genni, go to bed,” Mama called after her with a tired voice. “I’ll check on you in a minute.”

On her mother’s sixth day in Vietnam, Gen sat beside her father on the mauve couch in the den and watched the CBS Evening News. A man wearing a khaki vest reported that the first planeload of babies had taken off from the Saigon airport. President Ford had given his blessing. Operation Babylift was under way.

“They’re on that plane! Your mama and Nathaniel are coming home!” Her father called the boy Nathaniel; her mother called him Nhat.

Gen shook the Etch A Sketch she held on her lap, halfway erasing the staircase she had created. Mama and Nhat were coming home!

“That’s the way it is, Thursday, April 3, 1975,” Walter Cronkite said.

That’s the way it is. The words comforted her. Life couldn’t be helped; it happened. There was no way to change it; that’s just the way it was. But this was good news, not the bad news of the war with pictures showing naked children running from bombs, soldiers with cigarettes dangling out of their mouths and sadness in their eyes, and protesters screaming into the camera. No, this was good news. These babies had families waiting for them, and Mom and Nhat were on the plane!

“You need a haircut.” Her father peered down as if he hadn’t really seen Gen for six days. But she didn’t want a haircut. She wanted to grow it long, like her mom’s. Gen’s dark brown hair was tangled at the nape of her neck. Her mother usually braided it every morning before school. Gen had tried to keep it brushed, but still the tangles grew. Her father smiled at her affectionately, his gray eyes twinkling under his bushy eyebrows and full head of graying hair. Long sideburns framed his face.

He gazed around the dark, paneled den and then back to Gen. “Things will get back to normal now. We’ll be a family again. You’ll see.” Piles of papers leaned against each other on the coffee table, and clean clothes covered the vinyl hassock. Her father liked order. He said it was in his blood, from his German father. He stood and turned the knob on the Zenith television; the screen faded to a dark olive green.

“I’m hungry,” Gen said.

“Then I’ll make some eggs.” Daddy headed toward the kitchen. He hummed softly, which made Gen happy. They were going to be a family again; Mama was on the way home.

Gen stabbed at her egg and watched the yolk run onto the white Corelle plate. Her father always cooked the eggs just right. Nhat’s highchair with the red and blue plaid vinyl seat waited for him in the corner, and Gen imagined lifting him up to the chair and fitting the metal tray into the slots.

The phone rang. Her father jumped from the table, bumping his knee against the corner, and dashed to pick up the receiver.

“Hello,” he said. “Sally, is it you? Where are you? The line is bad. Can you hear me?”

How can Mom be calling if she’s on the plane?

Daddy cradled the receiver of the pink princess phone between his chin and shoulder and grabbed a pen and notepad off the desk. He leaned against the counter, the pen poised on the paper.

“You didn’t get on the plane? You’re still in Saigon?” He stood straight and took two steps to the center of the kitchen.

Gen took a deep breath and held it.

“You think you can get her out too?” He frowned as he talked, and his voice was stern. “You went to get Nathaniel out, not someone you worked with over a decade ago.”

Gen chewed on her bottom lip, trying not to cry. She wanted her mama to come home.

“Sally, I’m telling you. Get on that plane tomorrow with Nathaniel,” he pleaded. “For the love of God, for the love of us, get out of there.”

Daddy’s salt-and-pepper eyebrows rose in question marks. He was quiet for a minute. “No, no, I admire you for wanting to help her. But think of Nathaniel. Don’t risk him. Don’t risk everything we have.”

He was silent for another minute, and then his questions riddled the room. “What? Nathaniel is on the plane? The plane with all of the orphans? The one that flew out today? You put Nathaniel on the plane alone?” Her father turned and flung the pen onto the counter. “Promise me, Sally. Promise me you’ll get out on the next flight.” He stepped away from Gen and pulled the cord tight.

He fell silent as Mama spoke on the other end, nodding as if she could see him. As if she stood in the room with them. “Okay, okay,” he finally said. “We love you. We need you. Remember that. Just come home.”

Gen reached for the phone. She wanted to hear her mother’s voice; she wanted to tell Mama that she loved her too. But her father slammed down the receiver with a clatter as Gen’s hand hung in midair.

“Nathaniel’s on the plane coming out. Your mother stayed another day. She’s trying to help her friend Kim. They worked together at the mission. Your mom found her in Saigon.”

“When will we get Nathaniel?” Gen asked.

Her father shook his head. “I don’t know. The plane will land in San Francisco. Maybe he’ll stay in the Bay Area until Mama gets there. Maybe someone will escort him to Seattle or here to Portland.” He shrugged. “We’ll have to see how it all works out.”

Gen hurried down the stairs the next morning, dressed in her new bell-bottoms and her paisley blouse, ready for school. It was Friday. Perhaps on Saturday they would drive to Seattle and pick up Nhat. Maybe Mom would be there by then too. Her heart raced at the thought.

Her father sat frozen on a chair in the middle of the kitchen, the pink phone balanced on his knee, the receiver pressed against his ear. He wore his gray-striped flannel pajamas, and he hadn’t shaved. Why wasn’t he ready for work?

Gen walked into the den and turned on the morning news. She watched a Tide commercial and then heard the words “Tragedy in Vietnam.” She moved closer to the TV. A plane, loaded with babies, had crashed at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Airport; the first plane had landed in San Francisco. The newscaster said that the South Vietnamese officials couldn’t confirm why the plane had crashed, but authorities were investigating the possibility of a missile attack by the Viet Cong.

She sat down on the shag carpet and stared at the dark paneling that covered the walls until her father came into the den and turned off the TV.

“You saw?” His face appeared almost gray, the craggy lines around his eyes deeper than usual.

She nodded, biting her lip.

He folded his body down to the floor and sat beside her. “The call was from the U.S. Embassy. Mama died in the crash.” He put one arm around her and squeezed her tightly. Gen fell against him. Mom dead? Not her mama. Daddy began to pat her back, softly at first, then harder, jarring the sob that lodged between her heart and throat. Still the tears didn’t come.

Her father didn’t cry when he talked about her mother, but he did cry when he talked about Nhat. “Sally would want me to take him, I know. But I can’t. A child needs a mother. Nhat needs a mom.”

Why did he call her little brother Nhat now instead of Nathaniel? It scared her to watch her father cry. Why couldn’t Nhat come live with them anyway? Her chin started to tremble, but she ducked her head to hide her tears.

The day of the funeral Aunt Marie worked hard to brush the tangles out of Gen’s hair. Finally she smoothed the top layers over the knot at the base of Gen’s neck. Neither Daddy nor Gen cried during the church service; they sat in the front pew, hanging on to each other’s hands. Aunt Marie sat beside Gen and dabbed her eyes with a tissue. At the burial they huddled on metal chairs under a canopy, the black coffin in front of them, the open grave on the other side.

“Of course it won’t be an open casket,” Aunt Marie told a friend the day before the funeral. Overhearing the words gave Gen nightmares. What did her mother’s body look like? What was left? How badly had she been burned? Panic surged through her now as she stared at the casket.

“Dust to dust,” the pastor said. Gen shivered, holding tight to her father’s hand. The spring mist turned to rain. The group of mourners, hunched under umbrellas beside her mama’s grave, stared at Gen and her daddy.

Afterward, people filled the house. Aunt Marie pushed Gen’s bangs out of her eyes and then headed to the kitchen with the other women from their church. They seemed to multiply.

“Sally was so headstrong, so impulsive, so unsatisfied. It’s a good thing Genevieve is such an easy, practical child.” Aunt Marie’s words floated around Gen’s head as she stood in the kitchen doorway, feeling lost.

“It’s a pity that she looks so much like her mother though, small with that dark hair and those dark eyes–it will haunt Marshall,” said one of the church ladies. The women spoke in quiet voices but not low enough that Gen couldn’t hear.

“How could she have thought it was safe? Sally’s the only person I know who would do something like that. Shame on her for going to Vietnam in the first place.” Aunt Marie’s voice grew louder with each word.

No, Mama did the right thing. She and Daddy wanted Nhat. We all did. Gen had prayed for a baby brother for years. If only the plane hadn’t crashed. If only Mama and Nhat were here with her now. She walked into the living room and stood in front of the mantel, staring up at a picture of her parents. Her mother wore her hair in a french roll; her father’s eyes smiled. They stood side by side in front of their Dutch colonial house that overlooked the Rose City Golf Course.

Gen felt empty inside. Her throat thickened.

Her father knelt beside her. “How are you doing?”

Her lips began to tremble. He took her hand and led her out the front door to the porch steps. She tried not to cry for Mom. Tried not to cry for Nhat. If she couldn’t have her mother, why couldn’t she at least have her brother?

Her father patted her back.

“There, there,” he singsonged. Gen buried her face against his shoulder and began to sob.

The day after the funeral, Aunt Marie took Gen to the old-lady hair salon and told the beautician to cut Gen’s hair short, to get rid of all the tangles. Gen left with a pixie, a haircut that not even a six-year-old would wear. When they returned home, Aunt Marie cleared the stacks of papers out of the den. When he arrived home, Daddy scanned the den and nodded.

Then he noticed Gen and smiled faintly, without the twinkle that she loved. “Your hair looks good short. I like it.”

Gen ran to the mirror. She hated it. But it made her look less like her mother; maybe that’s why her father liked it.

Later that night he boxed up her mother’s things, including everything from Vietnam, even the family of place-card holders, except for the figurine of the girl that was propped against Gen’s lava lamp.

A week later her father pulled her mother’s dresses and her silk ao dai, the long Vietnamese tunic and trousers, out of her closet. Gen sat on her parents’ bed and held the garment in her arms. She breathed in her mother’s lilac scent. “She thought there could be peace, now, on this earth,” her father said. “She thought she could save the world.”

Gen nodded, pretending to agree to please her father, to ease his grief. She fingered the cross at her neck. She would wear it forever.

“She named you Genevieve because she thought it meant peace. It’s a lovely name, but it means white wave.” He sounded angry. “It was one of her many illogical decisions.”

Gen let go of the cross.

The correspondent on the CBS news reported the plane hadn’t been shot down; something had been wrong with the door. More than half of the three hundred passengers had been killed. Gen overheard her father tell Aunt Marie that Mom had been in the nose of the plane taking care of the babies, and that Nhat had gone to a family in Michigan.

The last Babylift took off on Saturday, April 26, 1975. Altogether, twenty-seven hundred children were evacuated.

The next day during Sunday school Aunt Marie, who taught the class, said, “All things work together for good to those who love God, to those who are the called according to his purpose.” She said it was a promise in the Bible.

Aunt Marie didn’t think that Gen’s mother had been called according to God’s purpose, so she probably meant that Gen had better be, otherwise things would never work out. When her mother quoted Bible verses, it sounded like poetry, like hope, like something good. When Aunt Marie quoted verses, it sounded like something bad was going to happen, something worse, something evil.

After Sunday school ended, Gen clicked her heels on the brown linoleum outside her classroom and thought about Aunt Marie’s words. She clicked her shoes again, this time harder. Gen liked the sound of her shoes in the hall. Aunt Marie walked toward her, wagging her finger. Her father said his sister was a pillar of the church, which made Gen imagine a statue of Aunt Marie holding up the sanctuary ceiling. The image made her smile and almost forget the scowl on Aunt Marie’s face.

That evening Gen watched the news again with her dad. The Viet Cong were launching rockets on Saigon. Gen watched the people on the roof of the U.S. Embassy trying to cross the barbed wire, trying to reach the helicopters, trying to get out. Her father shook his head. “Why couldn’t your mother have been content?” His voice was soft.

Gen nodded out of habit. She hoped that her mother’s friend Kim had made it out, hoped that she was safe.

Three days later she watched the news alone. Walter Cronkite’s face filled the screen. “That’s the way it is, Wednesday, April 30, 1975.” She turned and saw her father standing in the doorway.

“It’s all over.” Gen stood and picked up her spelling list off the vinyl hassock. The war was over, but she felt no peace.

That night she frantically shook her Etch A Sketch. She couldn’t stop. She had to make the whole staircase go away. The faded lines that she had drawn weeks before, the night the first Operation Babylift flight took off, had set in the sand. She hit herself in the forehead with the toy, and the red plastic split her skin.

Gen’s father reached for her, pulled her into his arms, and held her tight while blood dripped onto the wide collar of his dress shirt. She cried against his shoulder. The war was over, but there was no peace. No peace. No Mama. No Nhat. Her father washed her forehead, pressed a butterfly bandage over the wound, and then wrapped his arm around her as they sat silently on the couch in the den.

That night she dreamed about babies crying. Vietnamese babies who couldn’t stop crying. And blood dripping. She woke startled. The bandage on her forehead pulled the skin tight. If her mom were alive, Gen would tiptoe to her side of the bed, and her mama would reach out and pull her under the covers beside her. She might sing “Do Lord” softly. “I’ve got a home in glory land that outshines the sun…,” she would sing, and Gen would breathe in her lilac scent and feel Mama’s warm arms around her.

Gen closed her eyes and saw the dripping blood again. Her eyes flew open once more. “I’m the luckiest mother in the world,” her mother told her nearly every day. Gen would laugh and say, “No, you’re not.” Mama would answer, “Who? Who is luckier than I am?” And then Gen would relent and say she didn’t know, and her mom would laugh and say, “See? I am. I’m the luckiest mother in the world.”

Gen stared at her bedroom ceiling, at the outline of the crown molding in the dark. She reached for the figurine of the Vietnamese girl on the bedside table. “Mama, why wasn’t I enough?” She wrapped her fingers around the carving. “Why did you have to go to Vietnam? Why did you want another child?”

Gen sat cross-legged on her bed, clenching her fist around the figurine of the Vietnamese girl, digging her fingernails into her palm. Tomorrow her mother would leave for Vietnam. Gen closed her eyes.

Bombs exploded. Jungles burned. The Viet Cong marched toward Saigon. Nhat cried–all alone–in the orphanage.

Her eyes flew open.

She hadn’t been afraid when her mother traveled to the country a year ago. But now Gen was older; now she was nine; now she knew to be frightened.

Where was Mom? Her mother tucked her into bed every night. What was taking her so long?

Gen opened her hand. The figurine’s dark eyes shone above her tiny nose and lifelike smile; carved braids framed her face. She wore a red tunic and pants and held a miniature wooden doll.

“Time for bed!” Mom hurried into the room.

Mama. Gen squeezed her hand shut again, completely covering the carving.

Her mother sat next to Gen and pulled her close. “You’re going to be the best big sister ever.”

The red fluid in Gen’s lava lamp bubbled and cast a glow over her mom’s face. She was going to Vietnam to bring Nhat home; Gen would finally be a sister.

Her mom smoothed Gen’s dark hair back from her forehead. Her touch was gentle. “Are you worried about anything?”

Gen bit her lower lip and reached for her mother’s hand, holding it tight.

“About my leaving? About Nhat coming home to live with us?” Her mom leaned her cheek against the top of Gen’s head.

Gen snuggled closer. They had been waiting all year for the paperwork to be approved so they could adopt Nhat. She pictured her new little brother holding a bowl of rice, his only meal for the day.

“Mom?”

“What, sweetheart?”

“Does Nhat use chopsticks?”

Her mom smiled. “I don’t think so. He’s only two.”

Photos of Nhat hung on the refrigerator. He was only a year old when the pictures were taken; he was Amerasian with light skin and wavy hair, and he peered at Mom with adoring eyes and a big smile. In one picture, his hands were entwined in her long, dark hair.

“Will you teach him to use chopsticks?”

Her mother’s cheek still rested on Gen’s head. “Yes.”

“And me?”

“And you, Genni.” Genevieve was her given name. Mama was the only one who called her Genni.

Gen slowly opened her hand. The carving was part of a family of place-card holders that her mother bought last year in the open-air market in Saigon. “When will we use these?” Gen ran her finger along the slit that would hold a card in the girl’s back.

“When we have special dinners. Birthdays and holidays.” Her mom laughed a little. “You’ll see. I’ll cook more than Hamburger Helper when I get home. Things will calm down. I’ll spend all my time taking care of you and Nhat.”

“Tell me about Vietnam.” Gen settled her head onto her pillow and stretched out her legs, holding the girl in her open palm. Her mother had lived in Vietnam in 1961, when she was twenty-one, after graduating from nurses’ training. Gen never tired of hearing about her adventures.

“It was the most amazing year of my life.” Her mother stroked Gen’s hair as she spoke. “I lived in a hut with a thatched roof on a mission compound. I picked mangoes, coconuts, and bananas off the trees outside my door. I ate pho, noodle soup, for breakfast. Geckos scampered up the walls of my room and kept me company through the muggy nights. I made friends with a Vietnamese nurse named Kim, whom I love like a sister. I took care of people with leprosy who were missing fingers and toes, noses and ears.”

“Why didn’t you stay in Vietnam?”

“A doctor, a missionary, and a nurse were captured by the Viet Cong when I was home on furlough. My mission organization didn’t think I should return. Then I married your father. Then we had you.” Her mother smiled. Gen’s dad was eleven years older than her mom, but his age didn’t make him seem old, it made her mother seem young. They had met when her mom spoke at his church. Gen closed her hand over the figurine.

Mom put her hand over Gen’s and squeezed. “But I could never stop thinking about Vietnam; it was in my blood. That’s why I raised money and collected supplies for the orphans and hospitals. That’s why I went to Vietnam last year to work in the orphanage and help other people adopt. That’s why we’re adopting Nhat.”

“I want to go with you.” Gen reached for her mother’s hand. She wanted to go even though she would be afraid. She didn’t want her mother to go alone.

“I know.” Gen’s mom squeezed her fingers. “It’s too dangerous right now. Maybe we can go together someday.” She let go of Gen’s hand. “Try to keep your room clean while I’m gone. You know how much it bothers Daddy when it’s messy.”

Gen nodded.

“And be nice to Aunt Marie. She loves you. I know she can be harsh, but remember she’s hurting. She means well.”

Gen nodded again. Aunt Marie was her father’s sister; she would stay with Gen after school while Mom was gone. Her husband had died six months before, and sometimes it seemed that Aunt Marie was angry at everybody because of it. She criticized Gen’s mother’s housekeeping and cooking, Gen’s schoolwork and hair. Nothing felt right when Aunt Marie was around.

“Sally,” Gen’s father called to her mother from the hallway, “you still have to finish packing, and we have to get up early to take you to the airport.”

“G’night, sweetheart.” Gen’s mom leaned toward her. “Always remember how much I love you. Remember to trust God; that’s how you can show your faith. Remember that all things work together for good.” Her mother unclasped the gold chain of the jade cross that she wore and fastened it around Gen’s neck, kissing her forehead.

“I want you to wear this until I get back.” It was the only jewelry her mother ever wore besides her plain gold wedding band. Gen set aside the figurine and fingered the smooth, cool cross.

Her mom pulled her close and kissed her forehead. Gen breathed in her mother’s lilac scent. She touched the green stone again as her mother hugged her tight.

Before she fell asleep, Gen padded down the hall to the bathroom. As she passed her parents’ bedroom, she overheard them talking. Her father’s voice was deep and serious. “Sally, it’s a war zone over there.”

“We’ve waited long enough. If I don’t go now, we may never get Nhat out. What will happen to him?”

“Then I should go.” Her dad sounded worried.

Gen took a step closer to the door. Daddy wants to go to Vietnam? A suitcase lay open on the bed. A stack of disposable diapers leaned against it.

“No, Marshall, it will be much easier for me.”

Her father sat down on the edge of the bed. “I want this to be over. I want you to stop caring so much. We can continue to support the missionaries there, but I want you here with us. I don’t want you going back.”

“I doubt that there will be missionaries to support in Vietnam after this, not with the Viet Cong marching toward Saigon.” Gen’s mother picked up the diapers and wedged them into the suitcase. “The Communists will kick them out. There won’t be much I can do after this either. It’s my last chance.”

Her father put his head in his hands. Her mother turned toward the door. Gen ducked around the corner and into the bathroom.

“Genni, go to bed,” Mama called after her with a tired voice. “I’ll check on you in a minute.”

On her mother’s sixth day in Vietnam, Gen sat beside her father on the mauve couch in the den and watched the CBS Evening News. A man wearing a khaki vest reported that the first planeload of babies had taken off from the Saigon airport. President Ford had given his blessing. Operation Babylift was under way.

“They’re on that plane! Your mama and Nathaniel are coming home!” Her father called the boy Nathaniel; her mother called him Nhat.

Gen shook the Etch A Sketch she held on her lap, halfway erasing the staircase she had created. Mama and Nhat were coming home!

“That’s the way it is, Thursday, April 3, 1975,” Walter Cronkite said.

That’s the way it is. The words comforted her. Life couldn’t be helped; it happened. There was no way to change it; that’s just the way it was. But this was good news, not the bad news of the war with pictures showing naked children running from bombs, soldiers with cigarettes dangling out of their mouths and sadness in their eyes, and protesters screaming into the camera. No, this was good news. These babies had families waiting for them, and Mom and Nhat were on the plane!

“You need a haircut.” Her father peered down as if he hadn’t really seen Gen for six days. But she didn’t want a haircut. She wanted to grow it long, like her mom’s. Gen’s dark brown hair was tangled at the nape of her neck. Her mother usually braided it every morning before school. Gen had tried to keep it brushed, but still the tangles grew. Her father smiled at her affectionately, his gray eyes twinkling under his bushy eyebrows and full head of graying hair. Long sideburns framed his face.

He gazed around the dark, paneled den and then back to Gen. “Things will get back to normal now. We’ll be a family again. You’ll see.” Piles of papers leaned against each other on the coffee table, and clean clothes covered the vinyl hassock. Her father liked order. He said it was in his blood, from his German father. He stood and turned the knob on the Zenith television; the screen faded to a dark olive green.

“I’m hungry,” Gen said.

“Then I’ll make some eggs.” Daddy headed toward the kitchen. He hummed softly, which made Gen happy. They were going to be a family again; Mama was on the way home.

Gen stabbed at her egg and watched the yolk run onto the white Corelle plate. Her father always cooked the eggs just right. Nhat’s highchair with the red and blue plaid vinyl seat waited for him in the corner, and Gen imagined lifting him up to the chair and fitting the metal tray into the slots.

The phone rang. Her father jumped from the table, bumping his knee against the corner, and dashed to pick up the receiver.

“Hello,” he said. “Sally, is it you? Where are you? The line is bad. Can you hear me?”

How can Mom be calling if she’s on the plane?

Daddy cradled the receiver of the pink princess phone between his chin and shoulder and grabbed a pen and notepad off the desk. He leaned against the counter, the pen poised on the paper.

“You didn’t get on the plane? You’re still in Saigon?” He stood straight and took two steps to the center of the kitchen.

Gen took a deep breath and held it.

“You think you can get her out too?” He frowned as he talked, and his voice was stern. “You went to get Nathaniel out, not someone you worked with over a decade ago.”

Gen chewed on her bottom lip, trying not to cry. She wanted her mama to come home.

“Sally, I’m telling you. Get on that plane tomorrow with Nathaniel,” he pleaded. “For the love of God, for the love of us, get out of there.”

Daddy’s salt-and-pepper eyebrows rose in question marks. He was quiet for a minute. “No, no, I admire you for wanting to help her. But think of Nathaniel. Don’t risk him. Don’t risk everything we have.”

He was silent for another minute, and then his questions riddled the room. “What? Nathaniel is on the plane? The plane with all of the orphans? The one that flew out today? You put Nathaniel on the plane alone?” Her father turned and flung the pen onto the counter. “Promise me, Sally. Promise me you’ll get out on the next flight.” He stepped away from Gen and pulled the cord tight.

He fell silent as Mama spoke on the other end, nodding as if she could see him. As if she stood in the room with them. “Okay, okay,” he finally said. “We love you. We need you. Remember that. Just come home.”

Gen reached for the phone. She wanted to hear her mother’s voice; she wanted to tell Mama that she loved her too. But her father slammed down the receiver with a clatter as Gen’s hand hung in midair.

“Nathaniel’s on the plane coming out. Your mother stayed another day. She’s trying to help her friend Kim. They worked together at the mission. Your mom found her in Saigon.”

“When will we get Nathaniel?” Gen asked.

Her father shook his head. “I don’t know. The plane will land in San Francisco. Maybe he’ll stay in the Bay Area until Mama gets there. Maybe someone will escort him to Seattle or here to Portland.” He shrugged. “We’ll have to see how it all works out.”

Gen hurried down the stairs the next morning, dressed in her new bell-bottoms and her paisley blouse, ready for school. It was Friday. Perhaps on Saturday they would drive to Seattle and pick up Nhat. Maybe Mom would be there by then too. Her heart raced at the thought.

Her father sat frozen on a chair in the middle of the kitchen, the pink phone balanced on his knee, the receiver pressed against his ear. He wore his gray-striped flannel pajamas, and he hadn’t shaved. Why wasn’t he ready for work?

Gen walked into the den and turned on the morning news. She watched a Tide commercial and then heard the words “Tragedy in Vietnam.” She moved closer to the TV. A plane, loaded with babies, had crashed at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Airport; the first plane had landed in San Francisco. The newscaster said that the South Vietnamese officials couldn’t confirm why the plane had crashed, but authorities were investigating the possibility of a missile attack by the Viet Cong.

She sat down on the shag carpet and stared at the dark paneling that covered the walls until her father came into the den and turned off the TV.

“You saw?” His face appeared almost gray, the craggy lines around his eyes deeper than usual.

She nodded, biting her lip.

He folded his body down to the floor and sat beside her. “The call was from the U.S. Embassy. Mama died in the crash.” He put one arm around her and squeezed her tightly. Gen fell against him. Mom dead? Not her mama. Daddy began to pat her back, softly at first, then harder, jarring the sob that lodged between her heart and throat. Still the tears didn’t come.

Her father didn’t cry when he talked about her mother, but he did cry when he talked about Nhat. “Sally would want me to take him, I know. But I can’t. A child needs a mother. Nhat needs a mom.”

Why did he call her little brother Nhat now instead of Nathaniel? It scared her to watch her father cry. Why couldn’t Nhat come live with them anyway? Her chin started to tremble, but she ducked her head to hide her tears.

The day of the funeral Aunt Marie worked hard to brush the tangles out of Gen’s hair. Finally she smoothed the top layers over the knot at the base of Gen’s neck. Neither Daddy nor Gen cried during the church service; they sat in the front pew, hanging on to each other’s hands. Aunt Marie sat beside Gen and dabbed her eyes with a tissue. At the burial they huddled on metal chairs under a canopy, the black coffin in front of them, the open grave on the other side.

“Of course it won’t be an open casket,” Aunt Marie told a friend the day before the funeral. Overhearing the words gave Gen nightmares. What did her mother’s body look like? What was left? How badly had she been burned? Panic surged through her now as she stared at the casket.

“Dust to dust,” the pastor said. Gen shivered, holding tight to her father’s hand. The spring mist turned to rain. The group of mourners, hunched under umbrellas beside her mama’s grave, stared at Gen and her daddy.

Afterward, people filled the house. Aunt Marie pushed Gen’s bangs out of her eyes and then headed to the kitchen with the other women from their church. They seemed to multiply.

“Sally was so headstrong, so impulsive, so unsatisfied. It’s a good thing Genevieve is such an easy, practical child.” Aunt Marie’s words floated around Gen’s head as she stood in the kitchen doorway, feeling lost.

“It’s a pity that she looks so much like her mother though, small with that dark hair and those dark eyes–it will haunt Marshall,” said one of the church ladies. The women spoke in quiet voices but not low enough that Gen couldn’t hear.

“How could she have thought it was safe? Sally’s the only person I know who would do something like that. Shame on her for going to Vietnam in the first place.” Aunt Marie’s voice grew louder with each word.

No, Mama did the right thing. She and Daddy wanted Nhat. We all did. Gen had prayed for a baby brother for years. If only the plane hadn’t crashed. If only Mama and Nhat were here with her now. She walked into the living room and stood in front of the mantel, staring up at a picture of her parents. Her mother wore her hair in a french roll; her father’s eyes smiled. They stood side by side in front of their Dutch colonial house that overlooked the Rose City Golf Course.

Gen felt empty inside. Her throat thickened.

Her father knelt beside her. “How are you doing?”

Her lips began to tremble. He took her hand and led her out the front door to the porch steps. She tried not to cry for Mom. Tried not to cry for Nhat. If she couldn’t have her mother, why couldn’t she at least have her brother?

Her father patted her back.

“There, there,” he singsonged. Gen buried her face against his shoulder and began to sob.

The day after the funeral, Aunt Marie took Gen to the old-lady hair salon and told the beautician to cut Gen’s hair short, to get rid of all the tangles. Gen left with a pixie, a haircut that not even a six-year-old would wear. When they returned home, Aunt Marie cleared the stacks of papers out of the den. When he arrived home, Daddy scanned the den and nodded.

Then he noticed Gen and smiled faintly, without the twinkle that she loved. “Your hair looks good short. I like it.”

Gen ran to the mirror. She hated it. But it made her look less like her mother; maybe that’s why her father liked it.

Later that night he boxed up her mother’s things, including everything from Vietnam, even the family of place-card holders, except for the figurine of the girl that was propped against Gen’s lava lamp.

A week later her father pulled her mother’s dresses and her silk ao dai, the long Vietnamese tunic and trousers, out of her closet. Gen sat on her parents’ bed and held the garment in her arms. She breathed in her mother’s lilac scent. “She thought there could be peace, now, on this earth,” her father said. “She thought she could save the world.”

Gen nodded, pretending to agree to please her father, to ease his grief. She fingered the cross at her neck. She would wear it forever.

“She named you Genevieve because she thought it meant peace. It’s a lovely name, but it means white wave.” He sounded angry. “It was one of her many illogical decisions.”

Gen let go of the cross.

The correspondent on the CBS news reported the plane hadn’t been shot down; something had been wrong with the door. More than half of the three hundred passengers had been killed. Gen overheard her father tell Aunt Marie that Mom had been in the nose of the plane taking care of the babies, and that Nhat had gone to a family in Michigan.

The last Babylift took off on Saturday, April 26, 1975. Altogether, twenty-seven hundred children were evacuated.

The next day during Sunday school Aunt Marie, who taught the class, said, “All things work together for good to those who love God, to those who are the called according to his purpose.” She said it was a promise in the Bible.

Aunt Marie didn’t think that Gen’s mother had been called according to God’s purpose, so she probably meant that Gen had better be, otherwise things would never work out. When her mother quoted Bible verses, it sounded like poetry, like hope, like something good. When Aunt Marie quoted verses, it sounded like something bad was going to happen, something worse, something evil.

After Sunday school ended, Gen clicked her heels on the brown linoleum outside her classroom and thought about Aunt Marie’s words. She clicked her shoes again, this time harder. Gen liked the sound of her shoes in the hall. Aunt Marie walked toward her, wagging her finger. Her father said his sister was a pillar of the church, which made Gen imagine a statue of Aunt Marie holding up the sanctuary ceiling. The image made her smile and almost forget the scowl on Aunt Marie’s face.

That evening Gen watched the news again with her dad. The Viet Cong were launching rockets on Saigon. Gen watched the people on the roof of the U.S. Embassy trying to cross the barbed wire, trying to reach the helicopters, trying to get out. Her father shook his head. “Why couldn’t your mother have been content?” His voice was soft.

Gen nodded out of habit. She hoped that her mother’s friend Kim had made it out, hoped that she was safe.

Three days later she watched the news alone. Walter Cronkite’s face filled the screen. “That’s the way it is, Wednesday, April 30, 1975.” She turned and saw her father standing in the doorway.

“It’s all over.” Gen stood and picked up her spelling list off the vinyl hassock. The war was over, but she felt no peace.

That night she frantically shook her Etch A Sketch. She couldn’t stop. She had to make the whole staircase go away. The faded lines that she had drawn weeks before, the night the first Operation Babylift flight took off, had set in the sand. She hit herself in the forehead with the toy, and the red plastic split her skin.

Gen’s father reached for her, pulled her into his arms, and held her tight while blood dripped onto the wide collar of his dress shirt. She cried against his shoulder. The war was over, but there was no peace. No peace. No Mama. No Nhat. Her father washed her forehead, pressed a butterfly bandage over the wound, and then wrapped his arm around her as they sat silently on the couch in the den.

That night she dreamed about babies crying. Vietnamese babies who couldn’t stop crying. And blood dripping. She woke startled. The bandage on her forehead pulled the skin tight. If her mom were alive, Gen would tiptoe to her side of the bed, and her mama would reach out and pull her under the covers beside her. She might sing “Do Lord” softly. “I’ve got a home in glory land that outshines the sun…,” she would sing, and Gen would breathe in her lilac scent and feel Mama’s warm arms around her.

Gen closed her eyes and saw the dripping blood again. Her eyes flew open once more. “I’m the luckiest mother in the world,” her mother told her nearly every day. Gen would laugh and say, “No, you’re not.” Mama would answer, “Who? Who is luckier than I am?” And then Gen would relent and say she didn’t know, and her mom would laugh and say, “See? I am. I’m the luckiest mother in the world.”

Gen stared at her bedroom ceiling, at the outline of the crown molding in the dark. She reached for the figurine of the Vietnamese girl on the bedside table. “Mama, why wasn’t I enough?” She wrapped her fingers around the carving. “Why did you have to go to Vietnam? Why did you want another child?”

Descriere

Two girls from different worlds come into womanhood struggling to recover a sense of family--until their journeys suddenly converge. "Beyond the Blue" is the story of enormous losses, unthinkable choices, and the transforming power of God's love for the children of the world.