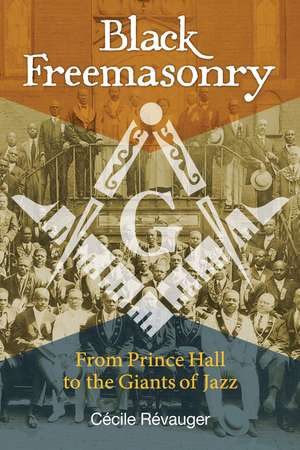

Black Freemasonry: From Prince Hall to the Giants of Jazz

Autor Cécile Révaugeren Limba Engleză Hardback – 28 ian 2016

Through privileged access to archives kept by Grand Lodges, Masonic libraries, and museums in both the United States and Europe, respected Freemasonry historian Cécile Révauger traces the history of black Freemasonry from Boston and Philadelphia in the late 1700s through the Abolition Movement and the Civil War to the genesis of the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1900s up through the 1960s.

Looking at the deep connections between jazz and Freemasonry, the author reveals how many of the most influential jazz musicians of the 20th century were also Masons. Unveiling the deeply social role at the heart of black Freemasonry, Révauger shows how the black lodges were instrumental in helping American blacks transcend the horrors of slavery and prejudice, achieve higher social status, and create their own solid spiritually based social structure, which in some cities arose prior to the establishment of black churches.

Preț: 171.98 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 258

Preț estimativ în valută:

32.91€ • 35.86$ • 27.73£

32.91€ • 35.86$ • 27.73£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-17 aprilie

Livrare express 19-25 martie pentru 93.40 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781620554876

ISBN-10: 1620554879

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: 29 b&w photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.66 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

ISBN-10: 1620554879

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: 29 b&w photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.66 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

Notă biografică

Cécile Révauger is a respected historian of Freemasonry and a professor at the University of Bordeaux. The author of several books on Freemasonry in French, she lives in the Bordeaux region of Southern France.

Extras

Nine

Jazzmen and Black Artists

The visitors to the National Jazz Museum, occupying a small hall on the top floor of a building in Harlem, receive a warm welcome because they are rare. If, in addition, they are knowledgeable enough to ask a few questions about Freemasonry, they will stupefy their hosts as it is still not common knowledge that Nat King Cole, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and many others were lodge members.

The histories written about jazz do not mention the Masonic membership of many musicians, although there may be some exceptions. The same is true for the biographical sketches posted by American National Biography.(2 ) We are in Raphael Imbert’s debt for the first books on jazz and Freemasonry.(3) Not only did he attempt to take a census of Freemason jazzmen, but he also deeply analyzed the spiritual dimension of jazz, which has heavily influenced American society since its golden age in the 1920s and throughout the twentieth century.(4) This does not mean, he says, “that there is some kind of masonic jazz. Or rather, there are no musical masonic rituals that can be identified as jazz.”

He breaks down the spiritual dimension of jazz into three tendencies: “religious, mystical, and metaphysical.”(5) He demonstrates that the religious dimension is an abiding presence for these musicians, much more than for most European musicians. In fact, the attitude of the American churches, which in most cases supported the fight against slavery and the civil rights movement, just like the lodges of Prince Hall, explains the attachment of many black masons to the religious tradition.

I am not going to focus on the “spiritual” dimension of the bond between jazz and Freemasonry as much as the social aspects. In fact the so-called Royal Art and the art of music have coupled harmoniously toaccompany the social rise of a large number of artists from poverty who also had to conront a society that was still strongly gripped by racial discrimination.

The Racist Context and Social Ascent of Jazzmen

Several of these musicians were born in dire poverty. In his autobiography, Satchmo,(6) Louis Armstrong describes the wretched condition in which his family lived in New Orleans during the years 1910–1920, in a neighborhood where violence and prostitution got on well with each other. As a teenager, he was sent to a juvenile home for firing a shot in the air to defend himself against a criminal threatening him. He also was a small-time pimp until he was able to make a living from his concerts.

His father, a worker in a turpentine factory, abandoned him at an early age, and he rarely saw him. It so happens that his father was a member of the Oddfellows, the mutual-aid society that often included the same members as the Prince Hall lodges. Armstrong recounts with pride how the Prince Hall lodges took part every year in the great parade as Grand Marshal.(7) Armstrong explains that all the clubs paraded in New Orleans: “The Oddfellows, the Masons, the Knights of Pythias (my lodge).”(8) He says he was also a member of the Tammany Soul and Pleasure Club.(9)

It is certain that these societies or clubs played a similar role to that of the Masonic lodges by affording their members social recognition that was all the more valuable as they were often of humble extraction and the victims of racial discrimination. At the end of the First World War, while playing concerts in New Orleans, Louis Armstrong was still obliged to deliver carts of coal in order to make a living.

Membership in Freemasonry conferred a guarantee of respectability and good morality. This was of such import that Dizzy Gillespie wrote in his autobiography that he was not initiated because he was living with a woman out of wedlock and had neglected to mention it to the lodge members, who learned of it on their own.(10)

Chicago attracted many jazz musicians such as Nat King Cole, whose family had decided to move there in 1923, when he was just four years old. The city, all the same, was not a haven from racist behavior, including that of “colored” people who wanted to assimilate completely into white society as shown by this incident that Nat King Cole experienced:

Once in Chicago, I sat down on a bus next to this light-skinned black lady, and she turned to me and said: “You are black and you stink and you can never wash it off.”(11)

These remarks, which were all the more hurtful coming from a black woman, left an indelible impression on Nat King Cole. Later, when the musician had successfully broken into an artistic milieu that was largely white, he had to confront many forms of discrimination or at least some unpleasant incidents. When he tried to buy what was a veritable palace--a fourteen-room home--in one of the most bourgeois neighborhoods of Los Angeles, Hancock Park, a homeowners’ association tried to oppose it by suing the seller. A year later, the B’nai Brith,(12) a Masonic-like Jewish organization, published a report denouncing the organizations guilty of discrimination against Blacks. Among them they cited the Hancock Park Homeowners Association that had harassed Nat King Cole and his wife.(13)

When Nat King Cole neglected to pay his taxes, his Cadillac and house were confiscated and the musician barely managed to hold on to his property by negotiating a repayment plan for his fiscal debts. Finally, during a concert tour in the South, he was physically attacked by four people in the middle of a concert in the city of Birmingham, Alabama. His assailants were arrested and convicted thanks to the support of the mayor of Birmingham and the determination of the judges, who were outraged by this openly racist assault.(14)

Jazzmen and Black Artists

The visitors to the National Jazz Museum, occupying a small hall on the top floor of a building in Harlem, receive a warm welcome because they are rare. If, in addition, they are knowledgeable enough to ask a few questions about Freemasonry, they will stupefy their hosts as it is still not common knowledge that Nat King Cole, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and many others were lodge members.

The histories written about jazz do not mention the Masonic membership of many musicians, although there may be some exceptions. The same is true for the biographical sketches posted by American National Biography.(2 ) We are in Raphael Imbert’s debt for the first books on jazz and Freemasonry.(3) Not only did he attempt to take a census of Freemason jazzmen, but he also deeply analyzed the spiritual dimension of jazz, which has heavily influenced American society since its golden age in the 1920s and throughout the twentieth century.(4) This does not mean, he says, “that there is some kind of masonic jazz. Or rather, there are no musical masonic rituals that can be identified as jazz.”

He breaks down the spiritual dimension of jazz into three tendencies: “religious, mystical, and metaphysical.”(5) He demonstrates that the religious dimension is an abiding presence for these musicians, much more than for most European musicians. In fact, the attitude of the American churches, which in most cases supported the fight against slavery and the civil rights movement, just like the lodges of Prince Hall, explains the attachment of many black masons to the religious tradition.

I am not going to focus on the “spiritual” dimension of the bond between jazz and Freemasonry as much as the social aspects. In fact the so-called Royal Art and the art of music have coupled harmoniously toaccompany the social rise of a large number of artists from poverty who also had to conront a society that was still strongly gripped by racial discrimination.

The Racist Context and Social Ascent of Jazzmen

Several of these musicians were born in dire poverty. In his autobiography, Satchmo,(6) Louis Armstrong describes the wretched condition in which his family lived in New Orleans during the years 1910–1920, in a neighborhood where violence and prostitution got on well with each other. As a teenager, he was sent to a juvenile home for firing a shot in the air to defend himself against a criminal threatening him. He also was a small-time pimp until he was able to make a living from his concerts.

His father, a worker in a turpentine factory, abandoned him at an early age, and he rarely saw him. It so happens that his father was a member of the Oddfellows, the mutual-aid society that often included the same members as the Prince Hall lodges. Armstrong recounts with pride how the Prince Hall lodges took part every year in the great parade as Grand Marshal.(7) Armstrong explains that all the clubs paraded in New Orleans: “The Oddfellows, the Masons, the Knights of Pythias (my lodge).”(8) He says he was also a member of the Tammany Soul and Pleasure Club.(9)

It is certain that these societies or clubs played a similar role to that of the Masonic lodges by affording their members social recognition that was all the more valuable as they were often of humble extraction and the victims of racial discrimination. At the end of the First World War, while playing concerts in New Orleans, Louis Armstrong was still obliged to deliver carts of coal in order to make a living.

Membership in Freemasonry conferred a guarantee of respectability and good morality. This was of such import that Dizzy Gillespie wrote in his autobiography that he was not initiated because he was living with a woman out of wedlock and had neglected to mention it to the lodge members, who learned of it on their own.(10)

Chicago attracted many jazz musicians such as Nat King Cole, whose family had decided to move there in 1923, when he was just four years old. The city, all the same, was not a haven from racist behavior, including that of “colored” people who wanted to assimilate completely into white society as shown by this incident that Nat King Cole experienced:

Once in Chicago, I sat down on a bus next to this light-skinned black lady, and she turned to me and said: “You are black and you stink and you can never wash it off.”(11)

These remarks, which were all the more hurtful coming from a black woman, left an indelible impression on Nat King Cole. Later, when the musician had successfully broken into an artistic milieu that was largely white, he had to confront many forms of discrimination or at least some unpleasant incidents. When he tried to buy what was a veritable palace--a fourteen-room home--in one of the most bourgeois neighborhoods of Los Angeles, Hancock Park, a homeowners’ association tried to oppose it by suing the seller. A year later, the B’nai Brith,(12) a Masonic-like Jewish organization, published a report denouncing the organizations guilty of discrimination against Blacks. Among them they cited the Hancock Park Homeowners Association that had harassed Nat King Cole and his wife.(13)

When Nat King Cole neglected to pay his taxes, his Cadillac and house were confiscated and the musician barely managed to hold on to his property by negotiating a repayment plan for his fiscal debts. Finally, during a concert tour in the South, he was physically attacked by four people in the middle of a concert in the city of Birmingham, Alabama. His assailants were arrested and convicted thanks to the support of the mayor of Birmingham and the determination of the judges, who were outraged by this openly racist assault.(14)

Cuprins

Foreword by Margaret C. Jacob, Ph.D.

Foreword by Peter P. Hinks, Ph.D.

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION

Interpreting the Black Experience

PART ONE

The Genesis of Black Freemasonry

ONE Prince Hall Legend and History 8

TWO The Birth of Black Freemasonry

THREE The Major Principles

PART TWO

A Militant Tradition

FOUR Abolitionism

FIVE Education

SIX The Fight for Civil Rights

PART THREE

A Community Takes Control of Its Own Destiny

SEVEN The Cooperative Ideal

EIGHT Women and Black Freemasonry

NINE Jazzmen and Black Artists

PART FOUR

The Parted Brothers

TEN The Brothers Who Were Excluded in the Name of the Great Principles

ELEVEN The Racism of White Freemasons

TWELVE Some Attempts to Come Together

THIRTEEN Prince Hall and the French Masonic Obediences

FOURTEEN The Perspective of Prince Hall Freemasons

The Separatist Temptation

FIFTEEN The Caribbean Masonic Space

Between Prince Hall and Europe

CONCLUSION To Each His Own Path

AFTERWORD A Question of Democracy by René Le Moal

Appendices

APPENDIX I Original Prince Hall Charter, General Regulations, and Petitions

APPENDIX II “Heroines of Jericho”

APPENDIX III Letters

APPENDIX IV Prince Hall Grand Lodges

Notes

Bibliography of Masonic Speeches and Annals

Bibliography

Index

Foreword by Peter P. Hinks, Ph.D.

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION

Interpreting the Black Experience

PART ONE

The Genesis of Black Freemasonry

ONE Prince Hall Legend and History 8

TWO The Birth of Black Freemasonry

THREE The Major Principles

PART TWO

A Militant Tradition

FOUR Abolitionism

FIVE Education

SIX The Fight for Civil Rights

PART THREE

A Community Takes Control of Its Own Destiny

SEVEN The Cooperative Ideal

EIGHT Women and Black Freemasonry

NINE Jazzmen and Black Artists

PART FOUR

The Parted Brothers

TEN The Brothers Who Were Excluded in the Name of the Great Principles

ELEVEN The Racism of White Freemasons

TWELVE Some Attempts to Come Together

THIRTEEN Prince Hall and the French Masonic Obediences

FOURTEEN The Perspective of Prince Hall Freemasons

The Separatist Temptation

FIFTEEN The Caribbean Masonic Space

Between Prince Hall and Europe

CONCLUSION To Each His Own Path

AFTERWORD A Question of Democracy by René Le Moal

Appendices

APPENDIX I Original Prince Hall Charter, General Regulations, and Petitions

APPENDIX II “Heroines of Jericho”

APPENDIX III Letters

APPENDIX IV Prince Hall Grand Lodges

Notes

Bibliography of Masonic Speeches and Annals

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“Eminently qualified to write about black Freemasonry, Cécile Révauger depicts with great accuracy how the split of American Freemasonry along racial lines arose and how it still persists, despite some progress within contemporary society. She also perfectly analyzes why it still remains difficult today to overcome prejudices, which are part of a legacy from the Founding Fathers. Her remarkable impartiality provides a balanced analysis of the present situation. Cécile’s work is an important addition to the world of scholarship as well as part of an effort to continue to build bridges in Freemasonry. I warmly recommend this book to every Mason wishing to better understand what kind of challenges remain today.”

“In her timely new book, Cécile Révauger offers a fresh examination of race, class, and social interaction in North America and the Caribbean, through the lens of three hundred years of Masonic history. What makes the study most remarkable is the unique perspective Révauger brings to the discussion of race relations in the Americas, giving readers the advantage of her scholarly expertise, as well as her privileged status within Masonry, to help us see into the sanctuary of an organization based on the equality of brothers, but which of necessity exists and works in a world rife with inequalities. The Masonic brethren she describes are men of their time and milieu, adapting in new ways the timeless ancient landmarks of Freemasonry to fit the needs and aspirations of their lodges and communities.”

“Cécile Révauger has done a commendable job documenting the struggles and triumphs of black Freemasonry in the United States. Her book should be required reading for all members of the Craft, regardless of their race or ethnicity. It is my sincere hope that the lessons learned from this scholarly study of the history of the Prince Hall Rite will establish, among all Freemasons, a new standard by which their capacity for brotherhood will be measured.”

“Masonic paradoxes embodied in a book! Black Freemasonry is not just about African American citizens joining a traditionally white fraternity. Cécile Révauger shows how this institution can be a place to seek freedom, create identity, or be enlightened but also can intensify divisions or encourage discrimination. A must-read for people interested in Masonic history, but also for anyone who wonders what equality, brotherhood, and inclusiveness mean.”

“Among the fascinating social and cultural insights offered by the history of Freemasonry and fraternal organizations, one of the most remarkable and most compelling stories is that of the role of African Americans in Freemasonry, particularly Prince Hall Freemasonry, established in Boston. In this engaging and accessible study, Professor Cécile Révauger provides an introduction to the history of blacks within Freemasonry, analyzing the racism and other obstacles they confronted. The story told by Professor Révauger is by turns heroic, unsettling, and thought provoking.”

“From the Revolution through abolitionism, the rise of jazz, and the civil rights movement, African American Freemasonry has played an important role in the central events of black history--and the history of America itself. Cécile Révauger’s book will allow more people to learn about this extraordinary fraternal movement.”

“Comprehensive and judicious in its approach, Black Freemasonry clearly lays out the complexities of Prince Hall Freemasonry’s history and tackles head on the heated debates that it has generated since its founding in the late eighteenth century. This didactic and richly illustrated volume should be read and appreciated by specialists and general readers alike.”

“. . . an invaluable guide to Prince Hall Freemasonry--and to an understanding of American race relations since Revolutionary times. While Freemasonry’s Enlightenment values of universal fellowship and tolerance failed to overcome the cultural challenge of American slavery and racism until recent decades, the author makes clear that black Freemasonry was an important part of the American civil rights movement. She discusses Prince Hall’s promulgation of the abolition of slavery soon after his first black lodge was chartered in 1784 and follows the political and cultural trail of both black and white Freemasonry ever since. Cécile Révauger sheds new light on the embrace of black Freemasonry by so many of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century and includes valuable historical documentation from the annals of Prince Hall Freemasonry in the well-crafted appendices.”

“Back in the early 18th century, when the first Masonic lodges opened their doors in Paris, membership was extended to men and women, both white and black, but not so here in the United States. In America, there arose an African American Freemasonry separate from that dominated by whites. The author is a respected historian of Freemasonry and a professor at France’s University of Bordeaux. The author reveals how the origins of the Civil Rights Movement arose from within black Freemasonry and how most of the influential jazz musicians of the 20th century, like Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole, W.C. Handy, and Cab Calloway, were black Masons.”

“In her timely new book, Cécile Révauger offers a fresh examination of race, class, and social interaction in North America and the Caribbean, through the lens of three hundred years of Masonic history. What makes the study most remarkable is the unique perspective Révauger brings to the discussion of race relations in the Americas, giving readers the advantage of her scholarly expertise, as well as her privileged status within Masonry, to help us see into the sanctuary of an organization based on the equality of brothers, but which of necessity exists and works in a world rife with inequalities. The Masonic brethren she describes are men of their time and milieu, adapting in new ways the timeless ancient landmarks of Freemasonry to fit the needs and aspirations of their lodges and communities.”

“Cécile Révauger has done a commendable job documenting the struggles and triumphs of black Freemasonry in the United States. Her book should be required reading for all members of the Craft, regardless of their race or ethnicity. It is my sincere hope that the lessons learned from this scholarly study of the history of the Prince Hall Rite will establish, among all Freemasons, a new standard by which their capacity for brotherhood will be measured.”

“Masonic paradoxes embodied in a book! Black Freemasonry is not just about African American citizens joining a traditionally white fraternity. Cécile Révauger shows how this institution can be a place to seek freedom, create identity, or be enlightened but also can intensify divisions or encourage discrimination. A must-read for people interested in Masonic history, but also for anyone who wonders what equality, brotherhood, and inclusiveness mean.”

“Among the fascinating social and cultural insights offered by the history of Freemasonry and fraternal organizations, one of the most remarkable and most compelling stories is that of the role of African Americans in Freemasonry, particularly Prince Hall Freemasonry, established in Boston. In this engaging and accessible study, Professor Cécile Révauger provides an introduction to the history of blacks within Freemasonry, analyzing the racism and other obstacles they confronted. The story told by Professor Révauger is by turns heroic, unsettling, and thought provoking.”

“From the Revolution through abolitionism, the rise of jazz, and the civil rights movement, African American Freemasonry has played an important role in the central events of black history--and the history of America itself. Cécile Révauger’s book will allow more people to learn about this extraordinary fraternal movement.”

“Comprehensive and judicious in its approach, Black Freemasonry clearly lays out the complexities of Prince Hall Freemasonry’s history and tackles head on the heated debates that it has generated since its founding in the late eighteenth century. This didactic and richly illustrated volume should be read and appreciated by specialists and general readers alike.”

“. . . an invaluable guide to Prince Hall Freemasonry--and to an understanding of American race relations since Revolutionary times. While Freemasonry’s Enlightenment values of universal fellowship and tolerance failed to overcome the cultural challenge of American slavery and racism until recent decades, the author makes clear that black Freemasonry was an important part of the American civil rights movement. She discusses Prince Hall’s promulgation of the abolition of slavery soon after his first black lodge was chartered in 1784 and follows the political and cultural trail of both black and white Freemasonry ever since. Cécile Révauger sheds new light on the embrace of black Freemasonry by so many of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century and includes valuable historical documentation from the annals of Prince Hall Freemasonry in the well-crafted appendices.”

“Back in the early 18th century, when the first Masonic lodges opened their doors in Paris, membership was extended to men and women, both white and black, but not so here in the United States. In America, there arose an African American Freemasonry separate from that dominated by whites. The author is a respected historian of Freemasonry and a professor at France’s University of Bordeaux. The author reveals how the origins of the Civil Rights Movement arose from within black Freemasonry and how most of the influential jazz musicians of the 20th century, like Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole, W.C. Handy, and Cab Calloway, were black Masons.”

Descriere

The history of black Freemasonry from Boston and Philadelphia in the late 1700s through the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement.