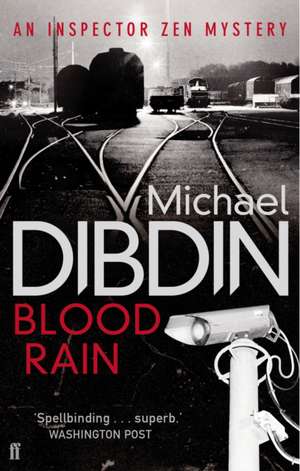

Blood Rain: Aurelio Zen

Autor Michael Dibdinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 17 feb 2011

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 64.35 lei 22-36 zile | +12.14 lei 5-11 zile |

| FABER & FABER – 17 feb 2011 | 64.35 lei 22-36 zile | +12.14 lei 5-11 zile |

| Vintage Crime/Black Lizard – 30 apr 2001 | 96.74 lei 22-36 zile |

Preț: 64.35 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 97

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.31€ • 12.78$ • 10.29£

12.31€ • 12.78$ • 10.29£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 februarie-10 martie

Livrare express 07-13 februarie pentru 22.13 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780571270835

ISBN-10: 0571270832

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 128 x 199 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

Seria Aurelio Zen

ISBN-10: 0571270832

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 128 x 199 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

Seria Aurelio Zen

Notă biografică

Michael Dibdin was born in England and raised in Northern Ireland. He attended Sussex University and the University of Alberta in Canada. He spent five years in Perugia, Italy, where he taught English at the local university. He went on to live in Oxford, England and Seattle, Washington. He was the author of eighteen novels, eleven of them in the popular Aurelio Zen series, including Ratking, which won the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger, and Cabal, which was awarded the French Grand Prix du Roman Policier. His work has been translated into eighteen languages. He died in 2007.

Extras

Chapter One

What it all seemed to come down to, in those early days when everything looked as clear as the sea at sunrise, was the question of exactly where, how and when the train had been 'made up'. It was only much later that Aurelio Zen came to realize that the train had been made up in a quite different sense, that it had never really existed in the first place.

At the time, the issues had seemed as solid as the train itself: a set of fourteen freight wagons currently quarantined on a siding in the complex of tracks surrounding the engine sheds at Piazza delle Americhe, on the coast to the north of central Catania. The site where the body had been found was within the territory of the provincia di Catania, and hence under the jurisdiction of the authorities of that city. So far, so good. From a bureaucratic point of view, however, the crucial factor was where and when the crime — if indeed it was a crime — had occurred. As all those concerned were soon to learn, none of these points was susceptible of a quick or easy answer.

Even assuming that the records provided by the State Railway authorities had been complete and credible, and no one in his right mind would have been prepared to make such an assumption, only a few unequivocal facts emerged. The first was that the train had originally left Palermo at 2.47 p.m. on 23 July. At this point it consisted of seven wagons, three of them empties commencing a long journey back to their depot in Catania, the others loaded with an assortment of goods ranging from empty wine bottles to drums of fertilizer. It was not clear whether or not the 'death chamber', as it was later dubbed by the media, had been one of these.

Having trundled along the north coast as far as the junction of Castello, the train turned inland, following a river valley up into the remote and largely depopulated centre of the island. Here, always assuming that the scanty records of the Ferrovie dello Stato were to be trusted, it had disappeared from official view for the best part of a week.

When it re-emerged on 29 July, at the junction of Caltanissetta-Xirbi, the convoy consisted of twelve wagons, including some — or possibly all — of the seven which had originally started from the island's capital. There had apparently been a lot of starting and stopping, of shunting and dropping, during the long, slow trip along the single-track line through the desolate interior of Sicily. No one was in any great hurry to get anywhere, and the staff in charge tended to make on-the-spot decisions about the composition and scheduling of such freight trains on a pragmatic basis, without bothering their superiors about every last detail. If the odd empty wagon got uncoupled or hitched up at some point, to keep the load down to what the ancient diesel locomotive could handle on the steep inland gradients, that was not regarded as a matter that needed to be brought to the attention of the officials in Palermo. Nor would the latter have been pleased to be in-formed about such minutiae, it being notorious that they had better things to do than their jobs.

At all events, the resulting train — whatever its exact composition — had continued via Caltanissetta and Canicattì to the coast and then headed east, picking up three (or possibly four) more wagons and losing one (or possibly two) to form the set now reposing on a secluded siding in Catania, its intended destination all along.

According to the subsequent deposition of the driver and his assistant, however, it had been stopped by a flagman near the unmanned station of Passo Martino, just south of Catania, and diverted into a siding there for several hours. This, they claimed to have been told, was due to emergency repair work on a bridge to the north. At length the flagman gave them the all-clear, and the freight train completed its journey without further incident, arriving on 1 August towards eight o'clock in the evening.

It was two days later that the State Railway offices in Catania received the phone call. The speaker had a smooth, educated voice, but his accent was unfamiliar to the official on duty. Apparently he wanted to report a public nuisance in the form of a wagonload of rotting goods parked on a siding at Passo Martino. The smell, he claimed, was dreadful, and what with the heat and the usual stench from the swampland all around, it was driving everyone out of their minds. Something should be done, and soon.

The railway official duly passed the message on to his superintendent. Maria Riesi would normally have dismissed the matter as just another crank call from some disgruntled eccentric, but under the circumstances she was only too happy to have an excuse to leave her stifling office and drive — all windows open, and the new Carmen Consuela album blasting from the speakers — down the autostrada to Piano d'Arci, and then along the country road which zigzagged across the river and the railway tracks to the lane leading down to the isolated station. She didn't believe for a moment that there would be anything there, but that didn't matter. The call had been duly logged and noted, so by going out to investigate she was merely doing her job.

Much to her surprise, there was a wagon there, parked on a set of rusted rails almost invisible beneath a scented mass of wild thyme punctuated by some scrubby cacti. There were other, less pleasant smells in the air too, and a lot of flies about. The sun was a strident scream, the heat reflected from every ambient surface its sonorous echo. Maria Riesi walked along the crumbling platform towards the rust-red bulk of the boxcar.

As a matter of routine, the first thing she checked was the waybill clipped into its holder beside the doors. This document listed Palermo as the origin of the wagon, and its destination as Catania. The writing was a mere scrawl, but the contents appeared to be listed as 'lemons', and the bill had been over-stamped in red with the word perishable. Judging by the swarms of flies and the nauseating stench, whatever the wagon contained was not only perishable, but had in fact perished. This came as no surprise to Maria, who knew very well that perishable goods did not travel in this type of wagon. It only remained to find out their nature, and if possible their provenance, and then write an anodyne report handing the whole matter over to Central Headquarters in Palermo. Let them decide whose head should roll.

Even standing on tiptoe, Maria Riesi could not reach the handle to open the wagon. But although short, she was both resourceful and strong. The station had been abandoned for years, but one of the large-wheeled baggage carts used to unload goods and luggage was still parked in a weed-infested corner of the platform, its handle propped up against the wall of a shed. Maria marched over and, grunting from the effort, managed to get it moving and to haul it over to the stalled wagon. She clambered up on to the slatted wooden floor of the cart, her silk blouse stained with sweat, and, by dint of putting her whole weight on the lever which secured the sliding door, eventually forced it open.

Everyone subsequently agreed that she had done more than could have been expected under the circumstances, and that it was not her fault that she vomited all over herself and the baggage cart. The post-mortem was conducted that evening, in an army tent hastily erected at the end of the platform, well away from the assembled group of policemen, magistrates and reporters. The remains had been removed from the wagon earlier by hospital personnel clad in plastic body suiting equipped with breathing apparatus. If the results of the examination were not very informative, this was due more to the condition of the corpse than to the pathologist's understandable desire to conclude the proceedings as soon as possible. The most he could say, based on a preliminary visual examination of the fly larvae present, was that the victim had been dead for at least a week.

Although the body had been discovered in the province of Catania, the ensuing investigation was technically speaking the responsibility of the police force having jurisdiction in the province where death had taken place. In the present case, this was an extremely moot point. In its peregrinations across Sicily, the train had passed through the provinces of Palermo, Caltanissetta, Palermo once again, Agrigento, Caltanissetta bis, Ragusa, Siracusa, and finally Catania. Six jurisdictions could thus assert a claim to investigate 'the Limina atrocity', to use another journalistic label soon attached to the affair. The wagon in which the corpse was found could not be traced with certainty to any of the many and only partially documented stops which the train had made, and even if it had, its original provenance as a 'death chamber' remained unknown.

None of this would have much mattered, of course, if it hadn't been for the provisional identification of the victim. On the contrary, everyone would have been only too happy to hand such a messy, unpromising case to their provincial neighbours on either side. Some vagrant had jumped a freight train somewhere down the line. He may have had a specific goal in mind, or just wanted to move on. Yet a further possibility was that he was on the run from someone or something, and needed to resort to clandestine forms of transport.

Unfortunately for him, the loading door on the wagon he selected had closed at some point after his entry. Perhaps he had even shut it himself, for greater security, not realizing that it could not be opened from the inside. Or maybe some jolting application of the brakes had done it, or simply the force of gravity acting on one of the gradients the train had climbed during its journey through the mountains.

At all events, the door had closed, locking the intruder inside. At that time of year, daytime temperatures reached well over one hundred degrees, even on the coast. Inside the sealed metal freight wagon, standing for days at a time on isolated sidings in the full glare of the sun, a hypothetical thermometer might well have recorded temperatures as high as one hundred and thirty.

Trapped inside that slow oven, the victim had recourse to nothing but his bare hands. His feet were also bare, and both were even barer by the time the body was discovered — stripped to the bone, in fact. The flesh had been abraded and pulped and the nails ripped off in the man's attempts to attract attention by hammering on the walls of the wagon and, when that failed, to pry open the door. No fingerprints, obviously. There wasn't much left of the face, either, which he had smashed repeatedly against a metal reinforcing beam, a frenzied effort at self-destruction indicating the intensity of the ordeal which he had sought to bring to a swift end.

The victim's pockets were completely empty, his clothing unmarked. In the absence of any other information it would have been almost impossible to identify him, except for that mysterious scribble in the Contents box on the wagon's waybill, which was eventually deciphered as being not 'limoni' — 'lemons' — but 'Limina'. It was this which ultimately led to the authorities in Catania being allotted jurisdiction in the case, for the Limina family ran one of the principal Mafia clans in that city, and Tonino, the eldest son and presumptive heir, had been rumoured to be missing for over a week.

The woman was standing at the corner of the bar, below a cabinet displaying various gilt and silver-plate soccer cups, photographs of the shrine of Saint Agatha, and a mirror reading, in English: 'Delicious Coca-Cola in the World the Most Refreshing Drink'. She was drinking a cappuccino and taking small, precise bites out of a pastry stuffed with sweetened ricotta cheese. In her early twenties, she was wearing a pale green linen dress and expensive sandals with heels. Her brown hair, streaked with blonde highlights, ran smoothly across her skull, secured by a white ribbon, then poured forth in a luxurious mane falling to her shoulders.

Nowhere else in Italy would this scene have rated a second of anyone's attention, but here it was seemingly a matter of some general concern, if not indeed scandal. For although the bar was crowded with traders and customers from the market taking place in the piazza outside, this woman was the sole representative of her sex present.

Not that anyone drew attention to her anomalous presence by any pointed comments, hard looks or tardy service. On the contrary, she was treated to an almost suffocating degree of respect and courtesy, in stark contrast to the rough-and-ready treatment handed out to the regulars. While they jammed as equals in the jazzy rhythms of male talk, fighting for the opportunity to take a solo, she was deferred to in an outwardly respectful but in practice exclusionary way. A request that her tepid coffee be reheated was met with a cry of 'Subito, signorina!' When she produced a cigarette, an outstretched lighter materialized before she had a chance to find her own, like a parody of a seduction scene in some old film.

But although the atmosphere was almost oppressively deferential, it could not have been said to be cordial. The other customers all clustered at the opposite end of the bar, or backed away towards the window and the door, creating a virtual exclusion zone around this lone female. Their voices were uncharacteristically low, too, and their mouths often casually covered by a hand holding a cigarette or obsessively brushing a moustache. For some reason, this unexceptionable woman appeared to be regarded as the social equivalent of an unexploded bomb.

When the man arrived, the palpable but undefined tension relaxed somewhat. It was as if one of the problems which the woman's presence represented had now been neutralized, although others perhaps remained. The newcomer was clearly not a local, even though his prominent, prow-like nose might have suggested some atavistic input from the Greek gene pool which still surfaced here from time to time, like the lava flows from the snow-covered volcano which dominated the city. But his accent, the pallor of his complexion, his stiff bearing and above all his height — a good head above everyone else in the room — clearly ruled him out as a Sicilian.

To look at, he and the woman might have been professional acquaintances or rivals meeting by chance over their morning coffee, but that hypothesis was abruptly dispelled by a gesture so quick and casual it could easily have passed unnoticed: the man reached over and turned down the label of the woman's dress, which was sticking up at the nape of her neck.

'A lei, Dottor Zen!' the barman announced at a volume which might or might not have been intended to undercut the politeness of the phrase. With a triumphant yet nonchalant gesture, he set down a double espresso and a pastry stuffed with sultanas, pine nuts and almond paste. Zen took a sip of the scalding coffee, which jolted his head back briefly, then pulled over the copy of the newspaper which the woman had been reading. DEATH CHAMBER WAGON TRACED TO PALERMO, read the headline. Aurelio Zen tapped the paper three times with the index finger of his left hand.

'So?' he asked, catching his companion's eyes.

The woman made a gesture with both hands, as though weighing a sack of some loose but heavy substance such as flour or salt.

'Not here,' she said.

And in fact the bar had suddenly become amazingly quiet, as though every single one of the adversarial conversations previously competing for territorial advantage had just happened to end at the same moment. Aurelio Zen turned to face the assembled customers, eyeing them in turn with an air which seemed to remind each of the company that he had urgent and pressing matters to discuss with his neighbours. Once the former hubbub was re-established, Zen turned back to start his breakfast.

'You're going native,' he said through a bite of the pastry.

'It's just common sense,' the woman replied, a little snappily. 'They know all about us, but we haven't the first idea about them.'

Zen finished his coffee and called for a glass of mineral water to wash down the sticky pastry.

'If you start thinking like that, you'll go mad.'

'And if you don't, you'll get killed.'

Zen snorted.

'Don't flatter yourself, Carla. Neither of us is going to get killed. We're not important enough.'

'Not to be a threat, no. But we're important enough to be a message.'

She pointed to the newspaper.

'Like him.'

'How do you mean?'

The woman did not answer. Zen finished his pastry and wiped his lips on a paper napkin tugged from its metal dispenser.

'Shall we?' he said, dropping a couple of banknotes on the counter.

Outside in Piazza Carlo Alberto, the Fera o Luni market was in full swing. Zen and his adopted daughter, Carla Arduini, had made this their meeting point from the moment that she had arrived in Sicily a month earlier, on a contract from her Turin computer firm to install a computer system for the Catania branch of the Direzione Investigativa AntiMafia. It was roughly half-way between the central police station, where Zen worked, and the Palazzo di Giustizia where Carla was battling with the complexities of setting up a network designed to be both totally secure and interactive with other DIA branches in Sicily and elsewhere.

Since arriving in the city, Zen had taken to leaving the window of his bedroom open so that he was awakened about five o'clock by the first birds and the barking of the local dogs, in time to watch the astonishing spectacle of sunrise over the Bay of Catania: an intense, distant glow, as though the sea itself had caught fire like a pan of oil. Then he showered, dressed, had a cup of homemade coffee and left the building, walking north beneath hanging gardens whose lemon trees, giant cacti and palms were teasingly visible above.

At about seven o'clock, he strode up to one of the conical-roofed booths in the Piazza Carlo Alberto which sold soft drinks, and ordered a spremuta d'arancia. In fact, he didn't need to order. The owner, who had spotted Zen's tall figure striding across the piazza, was already slicing blood-red oranges, dumping them in his ancient bronze press, and filling a glass with the pale orange-pink juice. Zen drank it down, then walked over to the café where he knew that Carla would be waiting for him. It was all very reassuring, like the rituals of the family he had never had.

When he and Carla emerged from the café, the sky above was delivering an impartial, implacable glare which merely hinted at the inferno to come later in the day, when every surface would add its note to the seamless cacophony of heat, radiating back the energy it had absorbed during hours of exposure to the midday sun.

A woman who looked about a hundred years old was roasting red and yellow peppers on a charcoal brazier, muttering some imprecation or curse to herself the while. Behind their wooden stalls drawn up in ranks in the square, under their faded acrylic parasols, traders with faces contorted into ritual masks either muttered a sales pitch in the form of a continual litany, as if reciting the Rosary, or barked their wares in harsh, rhetorical outbursts like the Messenger in some ancient play announcing a catastrophe unspeakable in normal language. This speech duly delivered, they surrendered the stage to one of their neighbours and reverted to being the unremarkable middle-aged men they were, gazing sadly at the goods whose praises they had just been singing, until the time came to don the tragic mask again and announce in a series of blood-curdling shrieks that plump young artichokes were to be had for seven hundred and fifty lire a kilo.

And not only artichokes. Just about every form of produce and merchandise known to man was on sale somewhere in the piazza, and those that were not on display — such as women, or AK-47s in their original packing cases — were available more discreetly in the surrounding streets. Zen and Carla walked through the meat section of the market, a shameless display which said, in effect, 'These are dead animals. We raise them, we kill them, then we eat them. If they're furry or have nice skin, we also wear them, but that's at the other end of the piazza.'

And it was this end that they had now entered, away from the specialist sellers of olives and peppers, fennel and cauliflowers, tomatoes and lettuce. Here it was all clothing, household goods and general kitsch and bric-à-brac, and a significant number of the traders were illegal extracommunitari immigrants from Libya, Tunisia and Algeria. An understood and accepted form of racism was in force: the locals wouldn't accept food from black hands, but they were perfectly happy to buy socks and tin-openers and screwdrivers from them, as long as the price was right.

'What were you saying about the body in the train?' asked Aurelio Zen as he and his companion passed the fringes of the market and emerged into the startlingly empty street beyond.

Carla glanced around before replying.

'The buzz in the women's toilet is that it wasn't the Limina boy at all.'

They walked in silence until they came to Via Umberto, their traditional parting place.

'Which judge is handling the case?' asked Zen.

'A woman called Nunziatella. First name Corinna.'

'Do you know her?'

'We've met a few times, and she seems to like me, but obviously I try to keep out of her way. A humble technician like me is not supposed to interfere with the work of the judges any more than is strictly necessary.'

Zen smiled, then kissed the woman briefly on both cheeks.

'Buon lavoro, Carla.'

'You too, Dad.'

What it all seemed to come down to, in those early days when everything looked as clear as the sea at sunrise, was the question of exactly where, how and when the train had been 'made up'. It was only much later that Aurelio Zen came to realize that the train had been made up in a quite different sense, that it had never really existed in the first place.

At the time, the issues had seemed as solid as the train itself: a set of fourteen freight wagons currently quarantined on a siding in the complex of tracks surrounding the engine sheds at Piazza delle Americhe, on the coast to the north of central Catania. The site where the body had been found was within the territory of the provincia di Catania, and hence under the jurisdiction of the authorities of that city. So far, so good. From a bureaucratic point of view, however, the crucial factor was where and when the crime — if indeed it was a crime — had occurred. As all those concerned were soon to learn, none of these points was susceptible of a quick or easy answer.

Even assuming that the records provided by the State Railway authorities had been complete and credible, and no one in his right mind would have been prepared to make such an assumption, only a few unequivocal facts emerged. The first was that the train had originally left Palermo at 2.47 p.m. on 23 July. At this point it consisted of seven wagons, three of them empties commencing a long journey back to their depot in Catania, the others loaded with an assortment of goods ranging from empty wine bottles to drums of fertilizer. It was not clear whether or not the 'death chamber', as it was later dubbed by the media, had been one of these.

Having trundled along the north coast as far as the junction of Castello, the train turned inland, following a river valley up into the remote and largely depopulated centre of the island. Here, always assuming that the scanty records of the Ferrovie dello Stato were to be trusted, it had disappeared from official view for the best part of a week.

When it re-emerged on 29 July, at the junction of Caltanissetta-Xirbi, the convoy consisted of twelve wagons, including some — or possibly all — of the seven which had originally started from the island's capital. There had apparently been a lot of starting and stopping, of shunting and dropping, during the long, slow trip along the single-track line through the desolate interior of Sicily. No one was in any great hurry to get anywhere, and the staff in charge tended to make on-the-spot decisions about the composition and scheduling of such freight trains on a pragmatic basis, without bothering their superiors about every last detail. If the odd empty wagon got uncoupled or hitched up at some point, to keep the load down to what the ancient diesel locomotive could handle on the steep inland gradients, that was not regarded as a matter that needed to be brought to the attention of the officials in Palermo. Nor would the latter have been pleased to be in-formed about such minutiae, it being notorious that they had better things to do than their jobs.

At all events, the resulting train — whatever its exact composition — had continued via Caltanissetta and Canicattì to the coast and then headed east, picking up three (or possibly four) more wagons and losing one (or possibly two) to form the set now reposing on a secluded siding in Catania, its intended destination all along.

According to the subsequent deposition of the driver and his assistant, however, it had been stopped by a flagman near the unmanned station of Passo Martino, just south of Catania, and diverted into a siding there for several hours. This, they claimed to have been told, was due to emergency repair work on a bridge to the north. At length the flagman gave them the all-clear, and the freight train completed its journey without further incident, arriving on 1 August towards eight o'clock in the evening.

It was two days later that the State Railway offices in Catania received the phone call. The speaker had a smooth, educated voice, but his accent was unfamiliar to the official on duty. Apparently he wanted to report a public nuisance in the form of a wagonload of rotting goods parked on a siding at Passo Martino. The smell, he claimed, was dreadful, and what with the heat and the usual stench from the swampland all around, it was driving everyone out of their minds. Something should be done, and soon.

The railway official duly passed the message on to his superintendent. Maria Riesi would normally have dismissed the matter as just another crank call from some disgruntled eccentric, but under the circumstances she was only too happy to have an excuse to leave her stifling office and drive — all windows open, and the new Carmen Consuela album blasting from the speakers — down the autostrada to Piano d'Arci, and then along the country road which zigzagged across the river and the railway tracks to the lane leading down to the isolated station. She didn't believe for a moment that there would be anything there, but that didn't matter. The call had been duly logged and noted, so by going out to investigate she was merely doing her job.

Much to her surprise, there was a wagon there, parked on a set of rusted rails almost invisible beneath a scented mass of wild thyme punctuated by some scrubby cacti. There were other, less pleasant smells in the air too, and a lot of flies about. The sun was a strident scream, the heat reflected from every ambient surface its sonorous echo. Maria Riesi walked along the crumbling platform towards the rust-red bulk of the boxcar.

As a matter of routine, the first thing she checked was the waybill clipped into its holder beside the doors. This document listed Palermo as the origin of the wagon, and its destination as Catania. The writing was a mere scrawl, but the contents appeared to be listed as 'lemons', and the bill had been over-stamped in red with the word perishable. Judging by the swarms of flies and the nauseating stench, whatever the wagon contained was not only perishable, but had in fact perished. This came as no surprise to Maria, who knew very well that perishable goods did not travel in this type of wagon. It only remained to find out their nature, and if possible their provenance, and then write an anodyne report handing the whole matter over to Central Headquarters in Palermo. Let them decide whose head should roll.

Even standing on tiptoe, Maria Riesi could not reach the handle to open the wagon. But although short, she was both resourceful and strong. The station had been abandoned for years, but one of the large-wheeled baggage carts used to unload goods and luggage was still parked in a weed-infested corner of the platform, its handle propped up against the wall of a shed. Maria marched over and, grunting from the effort, managed to get it moving and to haul it over to the stalled wagon. She clambered up on to the slatted wooden floor of the cart, her silk blouse stained with sweat, and, by dint of putting her whole weight on the lever which secured the sliding door, eventually forced it open.

Everyone subsequently agreed that she had done more than could have been expected under the circumstances, and that it was not her fault that she vomited all over herself and the baggage cart. The post-mortem was conducted that evening, in an army tent hastily erected at the end of the platform, well away from the assembled group of policemen, magistrates and reporters. The remains had been removed from the wagon earlier by hospital personnel clad in plastic body suiting equipped with breathing apparatus. If the results of the examination were not very informative, this was due more to the condition of the corpse than to the pathologist's understandable desire to conclude the proceedings as soon as possible. The most he could say, based on a preliminary visual examination of the fly larvae present, was that the victim had been dead for at least a week.

Although the body had been discovered in the province of Catania, the ensuing investigation was technically speaking the responsibility of the police force having jurisdiction in the province where death had taken place. In the present case, this was an extremely moot point. In its peregrinations across Sicily, the train had passed through the provinces of Palermo, Caltanissetta, Palermo once again, Agrigento, Caltanissetta bis, Ragusa, Siracusa, and finally Catania. Six jurisdictions could thus assert a claim to investigate 'the Limina atrocity', to use another journalistic label soon attached to the affair. The wagon in which the corpse was found could not be traced with certainty to any of the many and only partially documented stops which the train had made, and even if it had, its original provenance as a 'death chamber' remained unknown.

None of this would have much mattered, of course, if it hadn't been for the provisional identification of the victim. On the contrary, everyone would have been only too happy to hand such a messy, unpromising case to their provincial neighbours on either side. Some vagrant had jumped a freight train somewhere down the line. He may have had a specific goal in mind, or just wanted to move on. Yet a further possibility was that he was on the run from someone or something, and needed to resort to clandestine forms of transport.

Unfortunately for him, the loading door on the wagon he selected had closed at some point after his entry. Perhaps he had even shut it himself, for greater security, not realizing that it could not be opened from the inside. Or maybe some jolting application of the brakes had done it, or simply the force of gravity acting on one of the gradients the train had climbed during its journey through the mountains.

At all events, the door had closed, locking the intruder inside. At that time of year, daytime temperatures reached well over one hundred degrees, even on the coast. Inside the sealed metal freight wagon, standing for days at a time on isolated sidings in the full glare of the sun, a hypothetical thermometer might well have recorded temperatures as high as one hundred and thirty.

Trapped inside that slow oven, the victim had recourse to nothing but his bare hands. His feet were also bare, and both were even barer by the time the body was discovered — stripped to the bone, in fact. The flesh had been abraded and pulped and the nails ripped off in the man's attempts to attract attention by hammering on the walls of the wagon and, when that failed, to pry open the door. No fingerprints, obviously. There wasn't much left of the face, either, which he had smashed repeatedly against a metal reinforcing beam, a frenzied effort at self-destruction indicating the intensity of the ordeal which he had sought to bring to a swift end.

The victim's pockets were completely empty, his clothing unmarked. In the absence of any other information it would have been almost impossible to identify him, except for that mysterious scribble in the Contents box on the wagon's waybill, which was eventually deciphered as being not 'limoni' — 'lemons' — but 'Limina'. It was this which ultimately led to the authorities in Catania being allotted jurisdiction in the case, for the Limina family ran one of the principal Mafia clans in that city, and Tonino, the eldest son and presumptive heir, had been rumoured to be missing for over a week.

The woman was standing at the corner of the bar, below a cabinet displaying various gilt and silver-plate soccer cups, photographs of the shrine of Saint Agatha, and a mirror reading, in English: 'Delicious Coca-Cola in the World the Most Refreshing Drink'. She was drinking a cappuccino and taking small, precise bites out of a pastry stuffed with sweetened ricotta cheese. In her early twenties, she was wearing a pale green linen dress and expensive sandals with heels. Her brown hair, streaked with blonde highlights, ran smoothly across her skull, secured by a white ribbon, then poured forth in a luxurious mane falling to her shoulders.

Nowhere else in Italy would this scene have rated a second of anyone's attention, but here it was seemingly a matter of some general concern, if not indeed scandal. For although the bar was crowded with traders and customers from the market taking place in the piazza outside, this woman was the sole representative of her sex present.

Not that anyone drew attention to her anomalous presence by any pointed comments, hard looks or tardy service. On the contrary, she was treated to an almost suffocating degree of respect and courtesy, in stark contrast to the rough-and-ready treatment handed out to the regulars. While they jammed as equals in the jazzy rhythms of male talk, fighting for the opportunity to take a solo, she was deferred to in an outwardly respectful but in practice exclusionary way. A request that her tepid coffee be reheated was met with a cry of 'Subito, signorina!' When she produced a cigarette, an outstretched lighter materialized before she had a chance to find her own, like a parody of a seduction scene in some old film.

But although the atmosphere was almost oppressively deferential, it could not have been said to be cordial. The other customers all clustered at the opposite end of the bar, or backed away towards the window and the door, creating a virtual exclusion zone around this lone female. Their voices were uncharacteristically low, too, and their mouths often casually covered by a hand holding a cigarette or obsessively brushing a moustache. For some reason, this unexceptionable woman appeared to be regarded as the social equivalent of an unexploded bomb.

When the man arrived, the palpable but undefined tension relaxed somewhat. It was as if one of the problems which the woman's presence represented had now been neutralized, although others perhaps remained. The newcomer was clearly not a local, even though his prominent, prow-like nose might have suggested some atavistic input from the Greek gene pool which still surfaced here from time to time, like the lava flows from the snow-covered volcano which dominated the city. But his accent, the pallor of his complexion, his stiff bearing and above all his height — a good head above everyone else in the room — clearly ruled him out as a Sicilian.

To look at, he and the woman might have been professional acquaintances or rivals meeting by chance over their morning coffee, but that hypothesis was abruptly dispelled by a gesture so quick and casual it could easily have passed unnoticed: the man reached over and turned down the label of the woman's dress, which was sticking up at the nape of her neck.

'A lei, Dottor Zen!' the barman announced at a volume which might or might not have been intended to undercut the politeness of the phrase. With a triumphant yet nonchalant gesture, he set down a double espresso and a pastry stuffed with sultanas, pine nuts and almond paste. Zen took a sip of the scalding coffee, which jolted his head back briefly, then pulled over the copy of the newspaper which the woman had been reading. DEATH CHAMBER WAGON TRACED TO PALERMO, read the headline. Aurelio Zen tapped the paper three times with the index finger of his left hand.

'So?' he asked, catching his companion's eyes.

The woman made a gesture with both hands, as though weighing a sack of some loose but heavy substance such as flour or salt.

'Not here,' she said.

And in fact the bar had suddenly become amazingly quiet, as though every single one of the adversarial conversations previously competing for territorial advantage had just happened to end at the same moment. Aurelio Zen turned to face the assembled customers, eyeing them in turn with an air which seemed to remind each of the company that he had urgent and pressing matters to discuss with his neighbours. Once the former hubbub was re-established, Zen turned back to start his breakfast.

'You're going native,' he said through a bite of the pastry.

'It's just common sense,' the woman replied, a little snappily. 'They know all about us, but we haven't the first idea about them.'

Zen finished his coffee and called for a glass of mineral water to wash down the sticky pastry.

'If you start thinking like that, you'll go mad.'

'And if you don't, you'll get killed.'

Zen snorted.

'Don't flatter yourself, Carla. Neither of us is going to get killed. We're not important enough.'

'Not to be a threat, no. But we're important enough to be a message.'

She pointed to the newspaper.

'Like him.'

'How do you mean?'

The woman did not answer. Zen finished his pastry and wiped his lips on a paper napkin tugged from its metal dispenser.

'Shall we?' he said, dropping a couple of banknotes on the counter.

Outside in Piazza Carlo Alberto, the Fera o Luni market was in full swing. Zen and his adopted daughter, Carla Arduini, had made this their meeting point from the moment that she had arrived in Sicily a month earlier, on a contract from her Turin computer firm to install a computer system for the Catania branch of the Direzione Investigativa AntiMafia. It was roughly half-way between the central police station, where Zen worked, and the Palazzo di Giustizia where Carla was battling with the complexities of setting up a network designed to be both totally secure and interactive with other DIA branches in Sicily and elsewhere.

Since arriving in the city, Zen had taken to leaving the window of his bedroom open so that he was awakened about five o'clock by the first birds and the barking of the local dogs, in time to watch the astonishing spectacle of sunrise over the Bay of Catania: an intense, distant glow, as though the sea itself had caught fire like a pan of oil. Then he showered, dressed, had a cup of homemade coffee and left the building, walking north beneath hanging gardens whose lemon trees, giant cacti and palms were teasingly visible above.

At about seven o'clock, he strode up to one of the conical-roofed booths in the Piazza Carlo Alberto which sold soft drinks, and ordered a spremuta d'arancia. In fact, he didn't need to order. The owner, who had spotted Zen's tall figure striding across the piazza, was already slicing blood-red oranges, dumping them in his ancient bronze press, and filling a glass with the pale orange-pink juice. Zen drank it down, then walked over to the café where he knew that Carla would be waiting for him. It was all very reassuring, like the rituals of the family he had never had.

When he and Carla emerged from the café, the sky above was delivering an impartial, implacable glare which merely hinted at the inferno to come later in the day, when every surface would add its note to the seamless cacophony of heat, radiating back the energy it had absorbed during hours of exposure to the midday sun.

A woman who looked about a hundred years old was roasting red and yellow peppers on a charcoal brazier, muttering some imprecation or curse to herself the while. Behind their wooden stalls drawn up in ranks in the square, under their faded acrylic parasols, traders with faces contorted into ritual masks either muttered a sales pitch in the form of a continual litany, as if reciting the Rosary, or barked their wares in harsh, rhetorical outbursts like the Messenger in some ancient play announcing a catastrophe unspeakable in normal language. This speech duly delivered, they surrendered the stage to one of their neighbours and reverted to being the unremarkable middle-aged men they were, gazing sadly at the goods whose praises they had just been singing, until the time came to don the tragic mask again and announce in a series of blood-curdling shrieks that plump young artichokes were to be had for seven hundred and fifty lire a kilo.

And not only artichokes. Just about every form of produce and merchandise known to man was on sale somewhere in the piazza, and those that were not on display — such as women, or AK-47s in their original packing cases — were available more discreetly in the surrounding streets. Zen and Carla walked through the meat section of the market, a shameless display which said, in effect, 'These are dead animals. We raise them, we kill them, then we eat them. If they're furry or have nice skin, we also wear them, but that's at the other end of the piazza.'

And it was this end that they had now entered, away from the specialist sellers of olives and peppers, fennel and cauliflowers, tomatoes and lettuce. Here it was all clothing, household goods and general kitsch and bric-à-brac, and a significant number of the traders were illegal extracommunitari immigrants from Libya, Tunisia and Algeria. An understood and accepted form of racism was in force: the locals wouldn't accept food from black hands, but they were perfectly happy to buy socks and tin-openers and screwdrivers from them, as long as the price was right.

'What were you saying about the body in the train?' asked Aurelio Zen as he and his companion passed the fringes of the market and emerged into the startlingly empty street beyond.

Carla glanced around before replying.

'The buzz in the women's toilet is that it wasn't the Limina boy at all.'

They walked in silence until they came to Via Umberto, their traditional parting place.

'Which judge is handling the case?' asked Zen.

'A woman called Nunziatella. First name Corinna.'

'Do you know her?'

'We've met a few times, and she seems to like me, but obviously I try to keep out of her way. A humble technician like me is not supposed to interfere with the work of the judges any more than is strictly necessary.'

Zen smiled, then kissed the woman briefly on both cheeks.

'Buon lavoro, Carla.'

'You too, Dad.'

Recenzii

?As bracing as grappa.... Michael Dibdin is a fine novelist and an excellent mystery writer.??USA Today