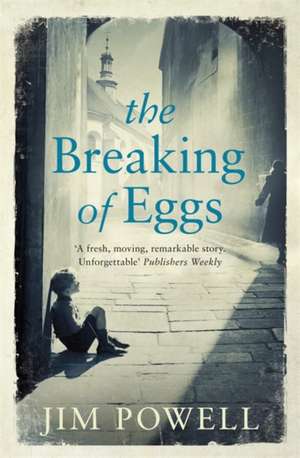

Breaking of Eggs: The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Antony Beevor

Autor Jim Powellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 16 mar 2011

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 92.77 lei 3-5 săpt. | +8.72 lei 6-12 zile |

| Phoenix Books – 16 mar 2011 | 92.77 lei 3-5 săpt. | +8.72 lei 6-12 zile |

| Penguin Books – 30 iun 2010 | 124.72 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 92.77 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 139

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.75€ • 18.53$ • 14.69£

17.75€ • 18.53$ • 14.69£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Livrare express 27 februarie-05 martie pentru 18.71 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780753827765

ISBN-10: 075382776X

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 199 x 133 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Phoenix Books

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 075382776X

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 199 x 133 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Phoenix Books

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Author is retired. Managing director in advertising. UK based. In his 50s. Ceramics business. Politics, speech-writer. Real name. Beatles - temping agency, asst. Lives in Northampton/London. 1st novel.

Recenzii

"A magnificent debut novel...a haunting, quietly brilliant story...a rare and remarkable achievement: a novel that meshes storytelling potency with historical erudition." -"The Boston Globe" "An impressive first novel...wise and witty." -"American Spectator" "Dramatic change comes to the rigidly ordered, solitary life of Feliks Zhukovski. A naturalized French citizen living in Paris, the irascible 61-year- old Polish leftist is stunned by the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union. He also gets the flu, and that spurs his first conversation in 36 years with his landlady. Feliks has always valued ideas and ideology over people, but events conspire to reunite him with the brother he hasn't seen for 50 years; take him to the hated U.S. to complete a business deal with capitalists (gasp!); discover the fate of his mother; and offer him a second chance at love. All of these events force Feliks to examine the choices he has made. Powell's delightful debut novel is by turns winsome and moving. Feliks is an indelible character, and the people who enter his life tell remarkable stories of the suffering that fascism and communism visited on Europe. "The Breaking of Eggs" is a book that thoughtful readers won't soon forget." -Thomas Gaughan, "Booklist"

Extras

I suppose that Madame Lefèvre was the catalyst for most of what happened next. This is surprising, since I doubt that Madame Lefèvre has otherwise been the catalyst for anything in her entire life. Even now I look at the words "catalyst" and "Madame Lefèvre" and wonder how they came to cohabit the same sentence.

'It's always good to be at home when you're ill, Monsieur Zhukovski.'

That was the first of two remarks which set in motion a chain of events that transformed my life in a way I would have found unimaginable at the time. It is hard to think of a more commonplace remark, a more unremarkable remark, yet it had such profound consequences.

'If you don't mind my saying so, Monsieur Zhukovski, you're getting a bit too old for all this running around. You should slow down, if you ask me.'

That was the second remark. At the time, I did mind her saying so, especially as I had not asked her, but it is hard to take offence when you are laid up in bed with a raging temperature and your self-appointed nurse chooses to offer unsought advice. So I probably said 'I expect you are right, Madame Lefèvre' and left it at that before receiving the sacrament of the latest parcel of medicines that she had procured at inordinate expense at the pharmacy across the street.

Both remarks were made on the same day: 1st January 1991. That made no impression on me at the time. I am not one to attach significance to such coincidences, or to any other superstitions or hocus-pocus, but now even I must admit that the date was appropriate. I had started to feel unwell on Christmas Eve and had thought nothing of it. Apart from the occasional cold, my health has always been good. I do not make a fuss about it. I do not announce the arrival of the 'flu the first time I blow my nose. As far as I can remember, I had never previously suffered the 'flu. Nor can I recall being ill in bed before.

To start with, I thought I was run down. 1990 had been a demanding year with a great deal of travel. I had needed to work harder and more rapidly than for a long time and I am sure it took a lot out of me. October and November had been especially difficult months. So when I started to feel unwell, in a way I was glad for the respite. Christmas is not my favourite time of year. I abhor the absurdities of religion. I have no family on whom to bestow unwanted presents. The handful of acquaintances who can normally be relied upon to help me prop up a bar in the evening all go to stay with relatives they detest. Paris closes down for a fortnight. There is nothing to do. Even without being ill, home is the best place to be; in fact the only place to be.

But I had never considered my apartment to be home, which is why Madame Lefèvre's remark made such a strong impression on me. It was not that I considered anywhere else to be home. I simply had no concept of home. I am not sure I had considered the question. There I was, a settled and comfortably-off man approaching his 61st birthday, who had lived in the same apartment for 36 years, and who was yet homeless. And the more I thought about that simple word "home", the more complicated it became for me. I realised it was not a word I used. When I returned from my travels each autumn, I did not think to myself 'I am going home'. When I put on my coat in some bar at the end of an evening, I did not say to my companions 'time to go home'. No. I would think 'I am going to Paris now', or say 'back to the apartment for me'. Home was not a word I used.

Perhaps this would have remained idle speculation but for Madame Lefèvre's second remark about being too old for all the running around. For the previous 36 years I had lived a life that others would perhaps call unusual and interesting, but which for me had long since become routine. In 1955 I started a small travel guide to the countries of Eastern Europe. Like many things that turn out to be important in one's life, it began almost by accident. I found myself out of work and needing to do something quickly. I was interested in travel. Particularly, I was interested in Eastern Europe. At the time I was a member of the French Communist Party and the idea of explaining Communist societies objectively to others appealed to me. It is true that there were relatively few tourists to Eastern Europe at that time, but there were some and no French travel guides were catering for them.

So I started the Guide Jaune. It was a modest publication initially. There was a section on every country within the Soviet bloc, each containing a brief commentary on the country, a description of principal cities and places of interest, and a list of hotels and restaurants. It had expanded over the years so that by 1991 it had become a sizeable volume. It sold steadily in independent bookshops in France. Later, German and English editions followed. Sales were never huge, but they were reliable and I managed to acquire a life that many people would envy: independent, varied and, if not exactly prosperous, then at least comfortable.

There were no staff. I was able to update the Guide quite easily myself, aided of course by helpful information from the tourist bureaux and government agencies in the various countries. My old friend Benoît Picard had printing works in Paris and he looked after the sales and distribution for me. Everything worked smoothly.

For all that time, I spent more than seven months each year travelling, setting out metronomically on 1st March and returning in early October, living out of a suitcase in the meantime. I made sure I visited each country and each major city at least once every two years. Some places—Moscow, Leningrad, Berlin, Warsaw, Prague, Budapest—I would visit annually. Another pattern followed my return to Paris each autumn. October was always a feverish month, in which I made the corrections and additions to the publication. The Guide was printed in the second half of November, so that the new edition could be in bookshops before Christmas, in time for people to plan their holidays for the following year. And this was how things continued for 36 years.

I must have known that at some point it would have to end, but I do not remember spending much time thinking about how or when it would happen, or what I would do with my life afterwards. But, even before Madame Lefèvre's remark, I had the sense that events were pressing in on me. It had started in 1989, of course. I still find the events of that year utterly bewildering. It would be fair to say that my own attachment to Communism was already weaker by then. I had ceased to be a Party member in 1968. But I remained, in principle, a supporter of what the Soviet system sought to achieve and I had no doubt about the permanence of that system in Eastern Europe, even if I no longer anticipated its triumph elsewhere. So, when the Soviet bloc collapsed like a pack of cards within a few months, I was astounded. I could not believe it was happening. It felt as if the entire edifice of my life was being torn down in front of me.

It was ironic, but the immediate effect of this on the Guide was most beneficial. Suddenly there was this new interest in tourism to Eastern Europe and mine was one of the few guides available. But I did not need to be a clairvoyant to know there would be many other consequential changes that would be less comfortable for me.

This became apparent during my travels in 1990. Everywhere I went, I encountered vast change. In less than a year, the situation had been transformed. All the old familiarities were evaporating. I found myself wondering whether more had not changed in a single year than in all the previous 35 put together. Naturally I cannot pretend that I thought most of this change had been for the better. I found the effect altogether unwholesome. It had also created severe pressure in my working life. Whereas previously it had been easy for me to update the Guide single-handedly, I could now see this was becoming impossible.

It was also becoming expensive. Perhaps I was stupid not to anticipate the personal greed that would follow such events. In March 1990 I had gone first to Prague, where I stayed in the same hotel as for many years. When I left, I was surprised to be presented with a bill. I assumed that the new manager could not have been informed of the arrangements but, when I summoned him, I was told bluntly that there no longer were any arrangements. I encountered the same situation elsewhere, to the extent that upon arrival anywhere I now needed first to check the financial status of my visit. I did not find this approach sympathetic. In fact it represented everything I loathed about the opening of Eastern Europe to capitalism.

So the entire summer of 1990 had been problematical in one way or another. Everything took longer than it had before. Everything cost more. I found myself in Warsaw at the end of September, torn between the imperative of visiting Berlin on my way back to Paris and the equal imperative of beginning the amendments to the 1991 edition immediately, as there were so many to make and so little time available. In the end I did not go to Berlin, although that may have owed something to my reluctance to be in the city on 3rd October, when East and West Germany were reunited. In any event, it was a major omission in the circumstances. I would be producing a guide for people to use in 1991 that had no first-hand account of the effects of the demolition of the Wall two years earlier. It was not good enough.

In spite of all this, I had no immediate intention of stopping the Guide. When, in October, I had received a letter from an American publisher asking if I might be interested in selling the title, I did not even bother to reply. I was in no mood to sell the Guide to anyone, and certainly not to some avaricious American firm. It was a temporary upheaval, I told myself: a lot of hard work for the time being and then everything would settle down again. Besides which, perhaps the Eastern Europeans—once they had sampled the unfairness of their new system—would decide they had not been so badly off after all.

The illness changed my attitude; the illness and Madame Lefèvre's remarks. Perhaps she was right. Perhaps I was getting too old for all this running around. Perhaps I had taken more out of myself in 1990 than I had realised. Perhaps it was time to think of retirement. But what would happen to the Guide? And to where would I retire? Where did people retire? They retired to home. And where was home?

'It's always good to be at home when you're ill, Monsieur Zhukovski.'

That was the first of two remarks which set in motion a chain of events that transformed my life in a way I would have found unimaginable at the time. It is hard to think of a more commonplace remark, a more unremarkable remark, yet it had such profound consequences.

'If you don't mind my saying so, Monsieur Zhukovski, you're getting a bit too old for all this running around. You should slow down, if you ask me.'

That was the second remark. At the time, I did mind her saying so, especially as I had not asked her, but it is hard to take offence when you are laid up in bed with a raging temperature and your self-appointed nurse chooses to offer unsought advice. So I probably said 'I expect you are right, Madame Lefèvre' and left it at that before receiving the sacrament of the latest parcel of medicines that she had procured at inordinate expense at the pharmacy across the street.

Both remarks were made on the same day: 1st January 1991. That made no impression on me at the time. I am not one to attach significance to such coincidences, or to any other superstitions or hocus-pocus, but now even I must admit that the date was appropriate. I had started to feel unwell on Christmas Eve and had thought nothing of it. Apart from the occasional cold, my health has always been good. I do not make a fuss about it. I do not announce the arrival of the 'flu the first time I blow my nose. As far as I can remember, I had never previously suffered the 'flu. Nor can I recall being ill in bed before.

To start with, I thought I was run down. 1990 had been a demanding year with a great deal of travel. I had needed to work harder and more rapidly than for a long time and I am sure it took a lot out of me. October and November had been especially difficult months. So when I started to feel unwell, in a way I was glad for the respite. Christmas is not my favourite time of year. I abhor the absurdities of religion. I have no family on whom to bestow unwanted presents. The handful of acquaintances who can normally be relied upon to help me prop up a bar in the evening all go to stay with relatives they detest. Paris closes down for a fortnight. There is nothing to do. Even without being ill, home is the best place to be; in fact the only place to be.

But I had never considered my apartment to be home, which is why Madame Lefèvre's remark made such a strong impression on me. It was not that I considered anywhere else to be home. I simply had no concept of home. I am not sure I had considered the question. There I was, a settled and comfortably-off man approaching his 61st birthday, who had lived in the same apartment for 36 years, and who was yet homeless. And the more I thought about that simple word "home", the more complicated it became for me. I realised it was not a word I used. When I returned from my travels each autumn, I did not think to myself 'I am going home'. When I put on my coat in some bar at the end of an evening, I did not say to my companions 'time to go home'. No. I would think 'I am going to Paris now', or say 'back to the apartment for me'. Home was not a word I used.

Perhaps this would have remained idle speculation but for Madame Lefèvre's second remark about being too old for all the running around. For the previous 36 years I had lived a life that others would perhaps call unusual and interesting, but which for me had long since become routine. In 1955 I started a small travel guide to the countries of Eastern Europe. Like many things that turn out to be important in one's life, it began almost by accident. I found myself out of work and needing to do something quickly. I was interested in travel. Particularly, I was interested in Eastern Europe. At the time I was a member of the French Communist Party and the idea of explaining Communist societies objectively to others appealed to me. It is true that there were relatively few tourists to Eastern Europe at that time, but there were some and no French travel guides were catering for them.

So I started the Guide Jaune. It was a modest publication initially. There was a section on every country within the Soviet bloc, each containing a brief commentary on the country, a description of principal cities and places of interest, and a list of hotels and restaurants. It had expanded over the years so that by 1991 it had become a sizeable volume. It sold steadily in independent bookshops in France. Later, German and English editions followed. Sales were never huge, but they were reliable and I managed to acquire a life that many people would envy: independent, varied and, if not exactly prosperous, then at least comfortable.

There were no staff. I was able to update the Guide quite easily myself, aided of course by helpful information from the tourist bureaux and government agencies in the various countries. My old friend Benoît Picard had printing works in Paris and he looked after the sales and distribution for me. Everything worked smoothly.

For all that time, I spent more than seven months each year travelling, setting out metronomically on 1st March and returning in early October, living out of a suitcase in the meantime. I made sure I visited each country and each major city at least once every two years. Some places—Moscow, Leningrad, Berlin, Warsaw, Prague, Budapest—I would visit annually. Another pattern followed my return to Paris each autumn. October was always a feverish month, in which I made the corrections and additions to the publication. The Guide was printed in the second half of November, so that the new edition could be in bookshops before Christmas, in time for people to plan their holidays for the following year. And this was how things continued for 36 years.

I must have known that at some point it would have to end, but I do not remember spending much time thinking about how or when it would happen, or what I would do with my life afterwards. But, even before Madame Lefèvre's remark, I had the sense that events were pressing in on me. It had started in 1989, of course. I still find the events of that year utterly bewildering. It would be fair to say that my own attachment to Communism was already weaker by then. I had ceased to be a Party member in 1968. But I remained, in principle, a supporter of what the Soviet system sought to achieve and I had no doubt about the permanence of that system in Eastern Europe, even if I no longer anticipated its triumph elsewhere. So, when the Soviet bloc collapsed like a pack of cards within a few months, I was astounded. I could not believe it was happening. It felt as if the entire edifice of my life was being torn down in front of me.

It was ironic, but the immediate effect of this on the Guide was most beneficial. Suddenly there was this new interest in tourism to Eastern Europe and mine was one of the few guides available. But I did not need to be a clairvoyant to know there would be many other consequential changes that would be less comfortable for me.

This became apparent during my travels in 1990. Everywhere I went, I encountered vast change. In less than a year, the situation had been transformed. All the old familiarities were evaporating. I found myself wondering whether more had not changed in a single year than in all the previous 35 put together. Naturally I cannot pretend that I thought most of this change had been for the better. I found the effect altogether unwholesome. It had also created severe pressure in my working life. Whereas previously it had been easy for me to update the Guide single-handedly, I could now see this was becoming impossible.

It was also becoming expensive. Perhaps I was stupid not to anticipate the personal greed that would follow such events. In March 1990 I had gone first to Prague, where I stayed in the same hotel as for many years. When I left, I was surprised to be presented with a bill. I assumed that the new manager could not have been informed of the arrangements but, when I summoned him, I was told bluntly that there no longer were any arrangements. I encountered the same situation elsewhere, to the extent that upon arrival anywhere I now needed first to check the financial status of my visit. I did not find this approach sympathetic. In fact it represented everything I loathed about the opening of Eastern Europe to capitalism.

So the entire summer of 1990 had been problematical in one way or another. Everything took longer than it had before. Everything cost more. I found myself in Warsaw at the end of September, torn between the imperative of visiting Berlin on my way back to Paris and the equal imperative of beginning the amendments to the 1991 edition immediately, as there were so many to make and so little time available. In the end I did not go to Berlin, although that may have owed something to my reluctance to be in the city on 3rd October, when East and West Germany were reunited. In any event, it was a major omission in the circumstances. I would be producing a guide for people to use in 1991 that had no first-hand account of the effects of the demolition of the Wall two years earlier. It was not good enough.

In spite of all this, I had no immediate intention of stopping the Guide. When, in October, I had received a letter from an American publisher asking if I might be interested in selling the title, I did not even bother to reply. I was in no mood to sell the Guide to anyone, and certainly not to some avaricious American firm. It was a temporary upheaval, I told myself: a lot of hard work for the time being and then everything would settle down again. Besides which, perhaps the Eastern Europeans—once they had sampled the unfairness of their new system—would decide they had not been so badly off after all.

The illness changed my attitude; the illness and Madame Lefèvre's remarks. Perhaps she was right. Perhaps I was getting too old for all this running around. Perhaps I had taken more out of myself in 1990 than I had realised. Perhaps it was time to think of retirement. But what would happen to the Guide? And to where would I retire? Where did people retire? They retired to home. And where was home?