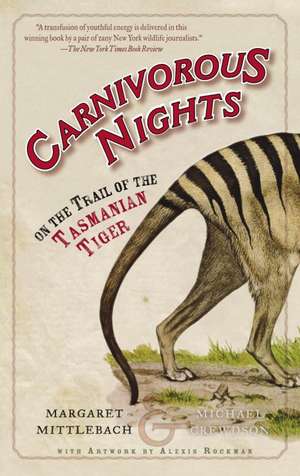

Carnivorous Nights: On the Trail of the Tasmanian Tiger

Autor Margaret Mittelbach, MICHAEL CREWDSON Ilustrat de Alexis Rockmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2006

Journeying first to the Australian mainland and then south to the wild island of Tasmania, these young naturalists brave a series of bizarre misadventures and uproarious wildlife encounters in their obsessive search for the long-lost beast. Filled with Rockman’s stunning drawings of flora and fauna originally crafted from river mud, wombat scat, and even the artist’s own blood, Carnivorous Nights is a hip and hilarious account of an unhinged safari, as well as a fascinating portrayal of a wildly unique part of the world.

Carniverous Nights is:

One of the New York Public Library's "25 Books to Remember from 2005"

A New York Public Library Books for the Teen Age, 2006 selection

Preț: 132.35 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 199

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.33€ • 26.35$ • 20.91£

25.33€ • 26.35$ • 20.91£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812967692

ISBN-10: 0812967690

Pagini: 319

Ilustrații: ILLUSTRATIONS THROUGHOUT; MAP

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Villard Books

ISBN-10: 0812967690

Pagini: 319

Ilustrații: ILLUSTRATIONS THROUGHOUT; MAP

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Villard Books

Notă biografică

MARGARET MITTELBACH and MICHAEL CREWDSON regularly join forces for The New York Times and other publications, employing their dry wit to reveal nature in the strangest of places. Their previous book, Wild New York, uncovered the unsung natural wonders of the city that never sleeps. They give frequent talks and lectures on wildlife, and live in Brooklyn.

Alexis Rockman’s artwork examines the history of how nature is portrayed, and is in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and London’s Saatchi Collection. He has also contributed artwork to several books, including Future Evolution, by Peter Ward, a prediction of the future of the global ecosystem. He lives and works in New York and has traveled around the world experiencing the wild firsthand.

From the Hardcover edition.

Alexis Rockman’s artwork examines the history of how nature is portrayed, and is in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and London’s Saatchi Collection. He has also contributed artwork to several books, including Future Evolution, by Peter Ward, a prediction of the future of the global ecosystem. He lives and works in New York and has traveled around the world experiencing the wild firsthand.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1. A Peculiar Animal

A few years ago we began visiting a stuffed and mounted animal skin with something akin to amorous fervor. We didn’t tell our friends about this secret relationship. We feared they would think it was unhealthy to be infatuated with a dead animal.

The object of our obsession resided at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan. Best known for its towering dinosaur skeletons and beautiful but creepy dioramas of gorillas and stuffed birds, the museum also housed a library where we did research. On the way there, we would walk through the perpetual twilight of the museum’s halls, passing meteorite fragments, African carvings, and a life-sized herd of motionless pachyderms.

When exactly we first saw this magnificent animal is lost in the recesses of memory, but we remember being instantly captivated by its exotic form. We marveled at its still limbs, at its head posed coyly downward, at its glorious Seussian stripes. It was a taxidermy of a Tasmanian tiger inside a rectangular glass case, and it was positioned in such a lifelike manner, its mouth curved in a friendly canine smile, that we found ourselves feeling affection for it as if it were a long-lost pet. It had fifteen dark brown stripes across the back of its ginger-colored coat, which is why it was called a tiger, but the stripes were where that resemblance ended. Its body was shaped more like a wolf’s or wild dog’s.

Discreetly tucked between the “Birds of the World” dioramas and a man-jaguar monster carved in jade, the tiger did not seem to be a very popular exhibit. Despite our own fascination, there was never a crowd around it. Many visitors walked by without giving it a glance. Admittedly, the tiger was not the museum’s newest attraction. In fact, it was an antique. A fading label said the animal from which it was fashioned died in 1919.

As the months passed, our attentions became more pointed. We spent our lunch breaks in front of the tiger, admiring its doggish head and wicket-shaped grin. We became so enamored that we began daydreaming about it while we were supposed to be reading about the mating behavior of horseshoe crabs in the library. Sometimes we imagined our tiger stalking through a generic jungle habitat in search of unknown prey, its bold stripes rippling through a scrim of green. We often wondered if Tasmania was as unlikely and exotic as the tiger itself.

Finally, we decided to do a background check on the specimen. The museum, in addition to its main library, had avenues of research normally off-limits to the public. But as nature writers we could always talk our way behind the scenes. We made an appointment to visit the museum’s mammal library, and when we walked in, it felt like we had traveled back in time or at least walked onto the set of a period film. There were heavy wooden railings, black wrought iron shelves, tiled glass walkways, and an old dumbwaiter. Near the door, cabinets filled with yellowing ledger books chronicled the mammalogy department’s acquisitions, starting in 1885. Each numbered entry, written in the feathery black ink of a fountain pen, listed the specimen’s scientific name, where it was collected, the name of the collector, and when the specimen was received.

We started to go through the entries, and it was daunting. There were thousands of them. Not being 100 percent familiar with the arcana of scientific nomenclature, we had to rely on fading memories of Greek and Latin studied years ago. For example, Volume 5 of the mammal catalogue listed no. 32732 as the skull of Loxodonta africana, an African elephant shot by Theodore Roosevelt “East of Meru Boma, just north of Kenia.” No. 27901 was the skull of Rangifer pearyi, a type of caribou, collected in the “Arctic Regions” by Commodore Robert E. Peary. No. 35185 was the skeleton of another Loxodonta africana, this one a circus elephant, donated by Barnum & Bailey. No. 35180 was the carcass of Canis familiaris, a domestic dog (actually a French poodle) collected at 621?2 East 125th Street in Manhattan and donated by a Dr. Blackburne. And finally there was our specimen. No. 35866 was the body of Thylacinus cynocephalus, donated by the Bronx Zoo in 1919.

We learned that the scientific name Thylacinus cynocephalus means “pouched animal with a dog head.” And the name thylacine (THY-luh-sine) was used almost as commonly as Tasmanian tiger. We also discovered that the animal was a marsupial, with a pouch like a kangaroo or a possum, and not closely related to tigers, wolves, dogs, or any of the familiar species it somewhat resembled. The museum’s thylacine had been caught in the wild on the island of Tasmania, brought to New York on a creaking ship, and displayed at the Bronx Zoo for two years. When it died, its body was sent over to the Museum of Natural History to be preserved.

Taxidermy has always been a strange art. From old letters in the library’s files, we gathered that the zoo frequently provided the museum with specimens of exotic animals. The zoo’s first director, William Temple Hornaday, had a strong interest in taxidermy, and the curator of the museum’s mammal department, J. A. Allen, had provided him with arsenic to help preserve the bodies, pelts, and skins. In this case, the tiger’s skin had been skillfully stitched to a wire-and-clay model and the result was an almost flawless simulacrum of a Tasmanian tiger.

Out of a collection of more than 32 million specimens, the Tasmanian tiger is designated one of the museum’s fifty most treasured items. Why? Because there are remarkably few specimens. The Tasmanian tiger is presumed to be extinct. That makes specimen no. 35866 rarer than a star sapphire, rarer than a Rembrandt.

The fact that our beloved tiger had a tragic past increased our interest. This rare species had lived in Tasmania for thousands of years and been the island’s top predator. But when the British colonized the island in the early nineteenth century, what had been an ark, floating serenely in southern seas, became a deathtrap. The tiger was considered a threat to the colonists’ livestock and they began hunting it down. A bounty was paid to anyone who brought in a dead tiger–and by the early part of the twentieth century, the Tasmanian tiger’s population began to hang in the balance.

On September 7, 1936, at a small zoo in Hobart, Tasmania’s capital, a thylacine (the last one in captivity anywhere in the world) passed away in the middle of the night. It’s believed that it died of exposure. Numerous searches were launched to replac it. Traps were set. But no more tigers, live or dead, were captured. The Hobart zoo’s thylacine became the proverbial “last tiger.” For the next fifty years, the searches continued, but no tangible evidence of the tiger was uncovered. In 1986, the thylacine was declared extinct by international standards. But this announcement did not fully penetrate on the island.

In Tasmania people continued to look for the tiger. What’s more people saw it. Multiple sightings of the thylacine are still reported each year. It’s seen chasing a wallaby, crossing a road, running along the island’s shore. These sightings raise a glimmer of hope that the species survives. How bright that glimmer was we didn’t know. The thrill of such a sighting swept over us. We imagined being in Tasmania and seeing a tiger gripping a dead kangaroo in its mouth, racing past our flickering campfire deep in the bush. We knew it was a long shot. But the tiger seemed to be calling our names.

Nearly seventy years after the last confirmed thylacine died, we stood in front of specimen no. 35866 at the Museum of Natural History. The taxidermy was so exquisite it seemed frozen in time. Sometimes we fantasized our tiger might be reanimated, that it might bust out of its glass case and trot down the museum’s halls, its smiling mouth gleaming with rows of sharp teeth as it bade adieu to the dusty old animals that complacently accepted their fate. Maybe it would bite a tourist on its way out the door.

Then one day we went to visit and the tiger wasn’t there. Its glass case was empty. A wave of panic swept over us. We asked around, but no one knew where it had gone. Finally, a clerk in the library told us she thought the thylacine had been moved to a temporary exhibit on genomics. Genomics? What was it doing there?

After navigating the museum’s long hallways and winding stairwells, we found it. The exhibit, called “The Genomics Revolution,” was jarring, filled with lights flashing the letters A, T, C, and G, the primary components of DNA. Miniature video screens surrounded a huge DNA model. The thylacine was hard to see and crammed in the very back. A card explained why the thylacine had been moved. Halfway across the world in an Australian lab, scientists were initiating a project to clone the Tasmanian tiger. Their goal was to bring this vanished species back to life. A specimen pickled in alcohol over one hundred years ago was said to have enough intact DNA to make it possible. Seeing our tiger friend in this new light gave us a chill. The thylacine was teetering unsteadily between the categories of “presumed extinct” and “soon-to-be-alive.” We didn’t know what to make of it. Apparently, we weren’t the only ones obsessed with this animal. We were overcome with a sudden urge to meet the people who believed the tiger was still lurking in its old island haunts, the scientists who planned to resurrect it, and the pundits who cast it into the oblivion of extinction. Maybe they could help us sort it all out.

We had recently written a book about New York City’s wildlife. Coyotes in the Bronx. Bald eagles flying over Central Park. Cockroaches in the kitchen sink. It was time, we decided, to explore something more exotic. Our friend Alexis Rockman, an artist with a similar fixation on nature, certainly thought so. He had been pestering us to go on a trip, some kind of working adventure, for years. We would write. He would paint. “Enough with the rats and pigeons,” he said. “Let’s blow this town.”

Alexis was the one person who knew about our relationship with the thylacine. His mother was an archaeologist who had worked at the natural history museum when he was a kid, and its hallways–filled with fossils, habitat dioramas, and dead animals–had been his childhood playground. He knew every inch of the place. As a result, he shared our fascination with the thylacine, though not to the same obsessive degree.

We found Alexis at his basement studio in Tribeca. He was adding tiny species of tropical butterflies to a five-foot-by-seven-foot scene of a South American rain forest.

What we would find hanging in Alexis’s studio was always a surprise. One week it might be a giant picture of a tree of life gone haywire. Another time it might be a self-portrait of Alexis, his own body lying dead and decomposing in a jungle. Or maybe raccoons having sex with roosters. His paintings were imbued with dark and disturbing images from the natural world–of species, extinction, evolution, and coming disaster. They pictured lurid landscapes filled with real and imaginary creatures.

The crammed bookshelves in his studio reflected these interests. Beside coffee-table books on artists such as Winslow Homer and Martin Johnson Heade, titles included the Golden Guide to Spiders and Their Kin, Dangerous Animals, and Dearest Pet: On Bestiality. He had his own small collection of taxidermy–as well as a well-loved (living) pet cat–and on his desk he kept a dried-out bat in a jar.

“We’ve just been to the museum,” we told him.

“Have you been indulging your thylacine fetish again?” He flicked a dot of red onto the wings of the butterfly he was painting. “That taxidermy’s so fucking beautiful–and incredibly sad.”

“So you think it’s extinct.”

“Of course.”

“You probably wouldn’t want to go to Tasmania then.”

He didn’t answer right away. Instead, he cleaned off his palette and put his brushes in turpentine. Then he stretched out on the floor of his studio with his shorts hiked up and took a drag on a joint. Though we were eager for him to say yes, we were anxious about what that might mean. Our eyes followed the thin column of smoke emanating from his mouth as we tried to picture what Alexis would be like as a traveling companion. On the one hand, he was superconfident, talented, and successful. Just over six feet tall, he had lanky, model good looks and magazines such as Vogue and Elle were nearly as likely to print a photo of him as they were one of his paintings. He was also athletic. He played highly competitive basketball and might have played college ball if Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts had fielded a team. Over the years, he had produced hundreds of drawings and paintings–oils, watercolors–that had sold through his Chelsea art gallery for millions of dollars. On the other hand, he oozed vibes of self-doubt, and his moods were unpredictable. He was a New York neurotic with a twist: George Costanza in the body of Narcissus. Nothing was ever enough. If he had a solo show at a gallery, he wanted a traveling museum retrospective that focused on his entire career. He was a workaholic, simultaneously driven and racked by anxiety, and at one time had smoked two and a half packs of Camel filters a day to calm himself down. Lately, he had switched from cigarettes to marijuana, and this self-prescribed after-hours hit of pot really seemed to do the trick, bringing his jittery brand of ambition down to the level of the average superachiever.

“Tasmania,” he said slowly. “I don’t know . . . I have to prepare for a big show in London next year.”

We had brought over our laptop and clicked on a forty-second black-and-white film of the Tasmanian tiger taken in 1933. Filmed at the Hobart zoo, the footage had a creepy air of unreality. The tiger–the last one confirmed to be alive–paced back and forth in its cage, showing off rangy, muscular legs and zebralike stripes. After a few seconds, it yawned, revealing a set of razor-sharp teeth, and extended its jaws almost impossibly wide. For a moment, it looked like a crocodile. Then it flopped down and lifted its big head like a dog.

“Holy shit,” Alexis said. “I would have killed to see that.”

Alexis pulled down a beat-up old atlas and opened it to a page showing a map of Australasia–New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Tasmania was a little triangle floating near the bottom, about 150 miles south of the Australian mainland. A dotted line ran through the blue ink of the Indian Ocean. It arced through the Malay Archipelago and cut a swath between the islands of Bali and Lombok, between Borneo and Sulawesi. It was marked “Wallace’s Line.”

From the Hardcover edition.

A few years ago we began visiting a stuffed and mounted animal skin with something akin to amorous fervor. We didn’t tell our friends about this secret relationship. We feared they would think it was unhealthy to be infatuated with a dead animal.

The object of our obsession resided at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan. Best known for its towering dinosaur skeletons and beautiful but creepy dioramas of gorillas and stuffed birds, the museum also housed a library where we did research. On the way there, we would walk through the perpetual twilight of the museum’s halls, passing meteorite fragments, African carvings, and a life-sized herd of motionless pachyderms.

When exactly we first saw this magnificent animal is lost in the recesses of memory, but we remember being instantly captivated by its exotic form. We marveled at its still limbs, at its head posed coyly downward, at its glorious Seussian stripes. It was a taxidermy of a Tasmanian tiger inside a rectangular glass case, and it was positioned in such a lifelike manner, its mouth curved in a friendly canine smile, that we found ourselves feeling affection for it as if it were a long-lost pet. It had fifteen dark brown stripes across the back of its ginger-colored coat, which is why it was called a tiger, but the stripes were where that resemblance ended. Its body was shaped more like a wolf’s or wild dog’s.

Discreetly tucked between the “Birds of the World” dioramas and a man-jaguar monster carved in jade, the tiger did not seem to be a very popular exhibit. Despite our own fascination, there was never a crowd around it. Many visitors walked by without giving it a glance. Admittedly, the tiger was not the museum’s newest attraction. In fact, it was an antique. A fading label said the animal from which it was fashioned died in 1919.

As the months passed, our attentions became more pointed. We spent our lunch breaks in front of the tiger, admiring its doggish head and wicket-shaped grin. We became so enamored that we began daydreaming about it while we were supposed to be reading about the mating behavior of horseshoe crabs in the library. Sometimes we imagined our tiger stalking through a generic jungle habitat in search of unknown prey, its bold stripes rippling through a scrim of green. We often wondered if Tasmania was as unlikely and exotic as the tiger itself.

Finally, we decided to do a background check on the specimen. The museum, in addition to its main library, had avenues of research normally off-limits to the public. But as nature writers we could always talk our way behind the scenes. We made an appointment to visit the museum’s mammal library, and when we walked in, it felt like we had traveled back in time or at least walked onto the set of a period film. There were heavy wooden railings, black wrought iron shelves, tiled glass walkways, and an old dumbwaiter. Near the door, cabinets filled with yellowing ledger books chronicled the mammalogy department’s acquisitions, starting in 1885. Each numbered entry, written in the feathery black ink of a fountain pen, listed the specimen’s scientific name, where it was collected, the name of the collector, and when the specimen was received.

We started to go through the entries, and it was daunting. There were thousands of them. Not being 100 percent familiar with the arcana of scientific nomenclature, we had to rely on fading memories of Greek and Latin studied years ago. For example, Volume 5 of the mammal catalogue listed no. 32732 as the skull of Loxodonta africana, an African elephant shot by Theodore Roosevelt “East of Meru Boma, just north of Kenia.” No. 27901 was the skull of Rangifer pearyi, a type of caribou, collected in the “Arctic Regions” by Commodore Robert E. Peary. No. 35185 was the skeleton of another Loxodonta africana, this one a circus elephant, donated by Barnum & Bailey. No. 35180 was the carcass of Canis familiaris, a domestic dog (actually a French poodle) collected at 621?2 East 125th Street in Manhattan and donated by a Dr. Blackburne. And finally there was our specimen. No. 35866 was the body of Thylacinus cynocephalus, donated by the Bronx Zoo in 1919.

We learned that the scientific name Thylacinus cynocephalus means “pouched animal with a dog head.” And the name thylacine (THY-luh-sine) was used almost as commonly as Tasmanian tiger. We also discovered that the animal was a marsupial, with a pouch like a kangaroo or a possum, and not closely related to tigers, wolves, dogs, or any of the familiar species it somewhat resembled. The museum’s thylacine had been caught in the wild on the island of Tasmania, brought to New York on a creaking ship, and displayed at the Bronx Zoo for two years. When it died, its body was sent over to the Museum of Natural History to be preserved.

Taxidermy has always been a strange art. From old letters in the library’s files, we gathered that the zoo frequently provided the museum with specimens of exotic animals. The zoo’s first director, William Temple Hornaday, had a strong interest in taxidermy, and the curator of the museum’s mammal department, J. A. Allen, had provided him with arsenic to help preserve the bodies, pelts, and skins. In this case, the tiger’s skin had been skillfully stitched to a wire-and-clay model and the result was an almost flawless simulacrum of a Tasmanian tiger.

Out of a collection of more than 32 million specimens, the Tasmanian tiger is designated one of the museum’s fifty most treasured items. Why? Because there are remarkably few specimens. The Tasmanian tiger is presumed to be extinct. That makes specimen no. 35866 rarer than a star sapphire, rarer than a Rembrandt.

The fact that our beloved tiger had a tragic past increased our interest. This rare species had lived in Tasmania for thousands of years and been the island’s top predator. But when the British colonized the island in the early nineteenth century, what had been an ark, floating serenely in southern seas, became a deathtrap. The tiger was considered a threat to the colonists’ livestock and they began hunting it down. A bounty was paid to anyone who brought in a dead tiger–and by the early part of the twentieth century, the Tasmanian tiger’s population began to hang in the balance.

On September 7, 1936, at a small zoo in Hobart, Tasmania’s capital, a thylacine (the last one in captivity anywhere in the world) passed away in the middle of the night. It’s believed that it died of exposure. Numerous searches were launched to replac it. Traps were set. But no more tigers, live or dead, were captured. The Hobart zoo’s thylacine became the proverbial “last tiger.” For the next fifty years, the searches continued, but no tangible evidence of the tiger was uncovered. In 1986, the thylacine was declared extinct by international standards. But this announcement did not fully penetrate on the island.

In Tasmania people continued to look for the tiger. What’s more people saw it. Multiple sightings of the thylacine are still reported each year. It’s seen chasing a wallaby, crossing a road, running along the island’s shore. These sightings raise a glimmer of hope that the species survives. How bright that glimmer was we didn’t know. The thrill of such a sighting swept over us. We imagined being in Tasmania and seeing a tiger gripping a dead kangaroo in its mouth, racing past our flickering campfire deep in the bush. We knew it was a long shot. But the tiger seemed to be calling our names.

Nearly seventy years after the last confirmed thylacine died, we stood in front of specimen no. 35866 at the Museum of Natural History. The taxidermy was so exquisite it seemed frozen in time. Sometimes we fantasized our tiger might be reanimated, that it might bust out of its glass case and trot down the museum’s halls, its smiling mouth gleaming with rows of sharp teeth as it bade adieu to the dusty old animals that complacently accepted their fate. Maybe it would bite a tourist on its way out the door.

Then one day we went to visit and the tiger wasn’t there. Its glass case was empty. A wave of panic swept over us. We asked around, but no one knew where it had gone. Finally, a clerk in the library told us she thought the thylacine had been moved to a temporary exhibit on genomics. Genomics? What was it doing there?

After navigating the museum’s long hallways and winding stairwells, we found it. The exhibit, called “The Genomics Revolution,” was jarring, filled with lights flashing the letters A, T, C, and G, the primary components of DNA. Miniature video screens surrounded a huge DNA model. The thylacine was hard to see and crammed in the very back. A card explained why the thylacine had been moved. Halfway across the world in an Australian lab, scientists were initiating a project to clone the Tasmanian tiger. Their goal was to bring this vanished species back to life. A specimen pickled in alcohol over one hundred years ago was said to have enough intact DNA to make it possible. Seeing our tiger friend in this new light gave us a chill. The thylacine was teetering unsteadily between the categories of “presumed extinct” and “soon-to-be-alive.” We didn’t know what to make of it. Apparently, we weren’t the only ones obsessed with this animal. We were overcome with a sudden urge to meet the people who believed the tiger was still lurking in its old island haunts, the scientists who planned to resurrect it, and the pundits who cast it into the oblivion of extinction. Maybe they could help us sort it all out.

We had recently written a book about New York City’s wildlife. Coyotes in the Bronx. Bald eagles flying over Central Park. Cockroaches in the kitchen sink. It was time, we decided, to explore something more exotic. Our friend Alexis Rockman, an artist with a similar fixation on nature, certainly thought so. He had been pestering us to go on a trip, some kind of working adventure, for years. We would write. He would paint. “Enough with the rats and pigeons,” he said. “Let’s blow this town.”

Alexis was the one person who knew about our relationship with the thylacine. His mother was an archaeologist who had worked at the natural history museum when he was a kid, and its hallways–filled with fossils, habitat dioramas, and dead animals–had been his childhood playground. He knew every inch of the place. As a result, he shared our fascination with the thylacine, though not to the same obsessive degree.

We found Alexis at his basement studio in Tribeca. He was adding tiny species of tropical butterflies to a five-foot-by-seven-foot scene of a South American rain forest.

What we would find hanging in Alexis’s studio was always a surprise. One week it might be a giant picture of a tree of life gone haywire. Another time it might be a self-portrait of Alexis, his own body lying dead and decomposing in a jungle. Or maybe raccoons having sex with roosters. His paintings were imbued with dark and disturbing images from the natural world–of species, extinction, evolution, and coming disaster. They pictured lurid landscapes filled with real and imaginary creatures.

The crammed bookshelves in his studio reflected these interests. Beside coffee-table books on artists such as Winslow Homer and Martin Johnson Heade, titles included the Golden Guide to Spiders and Their Kin, Dangerous Animals, and Dearest Pet: On Bestiality. He had his own small collection of taxidermy–as well as a well-loved (living) pet cat–and on his desk he kept a dried-out bat in a jar.

“We’ve just been to the museum,” we told him.

“Have you been indulging your thylacine fetish again?” He flicked a dot of red onto the wings of the butterfly he was painting. “That taxidermy’s so fucking beautiful–and incredibly sad.”

“So you think it’s extinct.”

“Of course.”

“You probably wouldn’t want to go to Tasmania then.”

He didn’t answer right away. Instead, he cleaned off his palette and put his brushes in turpentine. Then he stretched out on the floor of his studio with his shorts hiked up and took a drag on a joint. Though we were eager for him to say yes, we were anxious about what that might mean. Our eyes followed the thin column of smoke emanating from his mouth as we tried to picture what Alexis would be like as a traveling companion. On the one hand, he was superconfident, talented, and successful. Just over six feet tall, he had lanky, model good looks and magazines such as Vogue and Elle were nearly as likely to print a photo of him as they were one of his paintings. He was also athletic. He played highly competitive basketball and might have played college ball if Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts had fielded a team. Over the years, he had produced hundreds of drawings and paintings–oils, watercolors–that had sold through his Chelsea art gallery for millions of dollars. On the other hand, he oozed vibes of self-doubt, and his moods were unpredictable. He was a New York neurotic with a twist: George Costanza in the body of Narcissus. Nothing was ever enough. If he had a solo show at a gallery, he wanted a traveling museum retrospective that focused on his entire career. He was a workaholic, simultaneously driven and racked by anxiety, and at one time had smoked two and a half packs of Camel filters a day to calm himself down. Lately, he had switched from cigarettes to marijuana, and this self-prescribed after-hours hit of pot really seemed to do the trick, bringing his jittery brand of ambition down to the level of the average superachiever.

“Tasmania,” he said slowly. “I don’t know . . . I have to prepare for a big show in London next year.”

We had brought over our laptop and clicked on a forty-second black-and-white film of the Tasmanian tiger taken in 1933. Filmed at the Hobart zoo, the footage had a creepy air of unreality. The tiger–the last one confirmed to be alive–paced back and forth in its cage, showing off rangy, muscular legs and zebralike stripes. After a few seconds, it yawned, revealing a set of razor-sharp teeth, and extended its jaws almost impossibly wide. For a moment, it looked like a crocodile. Then it flopped down and lifted its big head like a dog.

“Holy shit,” Alexis said. “I would have killed to see that.”

Alexis pulled down a beat-up old atlas and opened it to a page showing a map of Australasia–New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Tasmania was a little triangle floating near the bottom, about 150 miles south of the Australian mainland. A dotted line ran through the blue ink of the Indian Ocean. It arced through the Malay Archipelago and cut a swath between the islands of Bali and Lombok, between Borneo and Sulawesi. It was marked “Wallace’s Line.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A transfusion of youthful energy is delivered in this winning book by a pair of zany New York wildlife journalists.”

–The New York Times Book Review

“Informed, colorful, often comical . . . hugely readable.”

–San Francisco Chronicle

“A rollicking safari . . . informative and entertaining.”

–The Oregonian (Portland)

“An adventure in extreme sleuthing . . . The true beauty of this volume is its depiction of the Tasmanian landscape in the raw. . . . Kudos are due the authors for the generous pace of their gaze [and] hilarious introspection.”

–Los Angeles Times

“A thrilling adventure . . . an irresistible work of armchair travel, not to be missed. Highly recommended.”

–Library Journal (starred review)

“A wonderful romp, part science and part Bill Bryson.”

–Booklist

–The New York Times Book Review

“Informed, colorful, often comical . . . hugely readable.”

–San Francisco Chronicle

“A rollicking safari . . . informative and entertaining.”

–The Oregonian (Portland)

“An adventure in extreme sleuthing . . . The true beauty of this volume is its depiction of the Tasmanian landscape in the raw. . . . Kudos are due the authors for the generous pace of their gaze [and] hilarious introspection.”

–Los Angeles Times

“A thrilling adventure . . . an irresistible work of armchair travel, not to be missed. Highly recommended.”

–Library Journal (starred review)

“A wonderful romp, part science and part Bill Bryson.”

–Booklist

Descriere

Comic travel writing in the tradition of Bill Bryson, the first mainstream book about Tasmania is perfect for armchair explorers and nature lovers. Along with descriptions of bizarre species and Tasmania's surprising history, the book is laced with Rockman's evocative artwork--originally crafted from organic materials picked up on this postmodern safari.