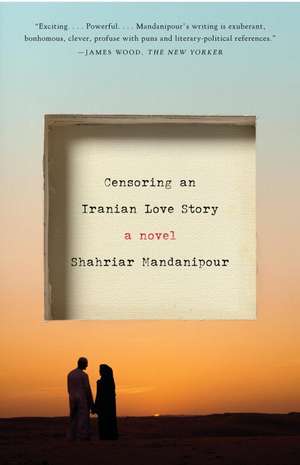

Censoring an Iranian Love Story

Autor Shahriar Mandanipour Traducere de Sara Khalilien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2010

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 48.86 lei 3-5 săpt. | +24.95 lei 4-10 zile |

| Little Brown Book Group – 3 feb 2011 | 48.86 lei 3-5 săpt. | +24.95 lei 4-10 zile |

| Vintage Books USA – 31 mai 2010 | 121.82 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 121.82 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 183

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.31€ • 24.08$ • 19.40£

23.31€ • 24.08$ • 19.40£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307390424

ISBN-10: 030739042X

Pagini: 295

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 030739042X

Pagini: 295

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Shahriar Mandanipour has won numerous awards for his novels, short stories, and nonfiction in Iran, although he was unable to publish his fiction from 1992 until 1997 as a result of censorship. He came to the United States in 2006 as the third International Writers Project Fellow at Brown University. He is currently a visiting scholar at Harvard University and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His work has appeared in PEN America, The Literary Review, and The Kenyon Review.

Visit the author's website at www.mandanipour.net.

Visit the author's website at www.mandanipour.net.

Extras

DEATH TO DICTATORSHIP, DEATH TO FREEDOM

In the air of Tehran, the scent of spring blossoms, carbon monoxide, and the perfumes and poisons of the tales of One Thousand and

One Nights, sway on top of each other, they whisper together. The city drifts in time.

In front of the main entrance of Tehran University, on Liberty Street, a crowd of students is gathered in political protest. With their fists raised they shout, “Death to captivity!” Across the street, members of the Party of God, with clenched fists and perhaps chains and brass knuckles in their pockets, shout “Death to the Liberal . . .”

The antiriot police, armed with the most sophisticated paraphernalia, including stun batons purchased from the West, stand facing the students. Both groups try, before they come to blows, to triumph over their opponents by shouting even louder. Drops of sweat ooze from faces and specks of spit spew from mouths. Fists, before pounding on heads, rise without miracle toward the sky.

It is perhaps because of these fists that from the sacred sky of Iran no miracle ever descends. Since one hundred and one years ago—when the first revolution for democracy triumphed in Iran—fists similar to these have risen toward the sky of a country with the greatest number of holy men, with the most prayers, tears, and religious lamentations; and today, I believe, the greatest pleas to God for speeding up the day of resurrection rise from Iran.

A short distance away, on the sidewalk, with her back to the steel fence lodged in the three- foot- tall stone wall surrounding Tehran University, stands a girl who, unlike most girls in the world but like most girls in Iran, is wearing a black headscarf and a long black coat as a coverall. She possesses a beauty common to all girls in love stories, a beauty that many girls around the world, and in Iran, who read these stories want to possess. If the ghosts of the thousands of poets who died a thousand years ago, seven hundred years ago, or four hundred years ago, and the spirit of those yet to be born—who, unlike the living, in the democracy of death amicably and tolerantly wander the streets of Tehran—see her large black eyes, they will liken them, as is customary of their poetry, to the sad eyes of a gazelle. An old simile for a pair of Oriental eyes that stole Lord Byron’s heart, and Arthur Rimbaud’s, too . . . But contrary to this clichéd simile, there is a mysterious look in this girl’s eyes. It is as if they possess the power to traverse time, the power to pass through the golden walls of harems or perhaps the firewalls of Web sites and Internet filters.

But the girl does not know that in precisely seven minutes and seven seconds, at the height of the clash between the students, the police, and the members of the Party of God, in the chaos of attacks and escapes, she will be knocked into with great force, she will fall back, her head will hit against a cement edge, and her sad Oriental eyes will forever close . . .

The girl attracts the attention of mysterious people who during political demonstrations in Iran monitor the scene from discreet corners and identify people. They point her out to one another. One of them, from a very professional angle, takes a photograph and films her. I know this girl is not a member of any political party, but she is timidly holding a sign that reads:

DEATH TO FREEDOM, DEATH TO CAPTIVITY

It is a strange slogan that I don’t believe has ever been seen or heard under the rule of any dictatorial, Communist, populist, or even so- called liberal regime. And I don’t believe it will ever be heard under the rule of any future regimes that for now remain nameless.

When they pause to catch their breath in between shouting their slogans, the students seeking freedom and democracy point to the girl and her sign and ask, “Who in the world is she? What is she trying to say?”

The more experienced students, old hands at political protests, respond:

“Completely ignore her. She’s an infiltrator. The Party of God has paid her to create distrust and division among us. To defuse the conspiracy,

just act as though she doesn’t exist.”

On the opposite side, the fanatic members of the Party of God also point to the girl and ask, “What’s that prissy girl trying to say over there?”

They hear from their leaders:

“The lewd hussy is one of those Communists who have recently come back to life. Their Big Brother in Russia is gaining strength again . . . but the pathetic slobs only have a handful of members in their party. This is how they hope to attract attention . . . Just ignore her. Act as though she doesn’t exist.”

With their wireless radios, the secret police pass along the girl’s location and ask, “What does this mean? We have no instructions for such cases. What should we do with her?” And they receive instructions:

“Watch her with extreme vigilance and caution. This is most definitely a new conspiracy and a new plot for a velvet revolution orchestrated by American imperialism . . . Keep her under surveillance but do not let her suspect anything. Let her think she doesn’t exist.”

Nameless shades of rage and hatred, voiceless cries of blood and hope and darkness, hang in the air. From one direction, meaning Anatole France Avenue, and from the other direction, meaning Revolution Circle, the police have blocked all car and pedestrian traffic to this section of Liberty Street. In Revolution Circle, hundreds of cars are logjammed, anxious and overwrought drivers blow their horns, and amid the cars curious people stand peering toward Tehran University. It was right here that more than a quarter century ago, on a cloudy winter day, the people of Tehran for the last time dragged down the metal statue of the Shah sitting astride a horse. Of course in those days, when it came to dragging down metal statues of dictators, American tanks sided with the world’s dictators.

The student protesters, aware that they are about to be attacked, break into a heartrending anthem:

My fellow schoolmate,

you are with me and beside me,

. . . you are my tear and my sigh,

. . . the scars of the lashes of tyranny rest on our bodies,

our uncultured wasteland, all its wild plants weeds,

be it good, be it bad,

dead are the souls of its people,

our hands must tear down these curtains,

who other than you and I can cure our pain . . .

In the lyrics and melody of this anthem lies an age- old Iranian sorrow that brings tears to the girl’s eyes . . . She raises her sign even higher. From behind the veil of her tears, the world is transformed into undulating buildings, severed shadows, and rippling reflections on water . . . The young girl’s isolation and her fear of strangers heighten. She looks up to find some solace in the blue of the sky. She sees a winged horse that like a white cloud, ignoring the people below, flies by. Terrified, she sees flames rising from the horse’s back. The blazing horse disappears behind a high- rise. The girl waits, but the horse does not reappear . . .

Then she imagines that in the midst of the shouts of anger and spite, a muffled voice is calling her name.

“Sara . . . ! Sara . . . !”

The girl wipes away her tears and looks around. There are people and shadows moving in every direction. It seems they are afraid of coming close to her.

“Dimwit . . . ! Dimwit . . . ! I’m talking to you!”

The voice bears the same chill and odor that gust out of a refrigerator that has not been opened in a month. The girl looks behind her. A

dark face, neckless and torsoless, is suspended in the air. Two of the steel bars in the green fence surrounding Tehran University that have broken out of the stone wall have sectioned the face in three . . . She thinks this face belongs to one of those sprites her grandmother said have parties in the city’s public bathhouses at night and that the only way to tell them apart from humans is by their hoofed feet . . .

“Hey! Dimwit! Get rid of that sign and escape! I’m talking to you . . . !”

Again the girl looks behind her. She sees that same fluid dark face on the other side of the fence. She thinks perhaps someone is squatting

down behind the wall and has lifted his head up to the fence.

“Hey! Daydreamer, go home! . . . Today death has it in for you. Go home! . . . Do you understand? It’s been half an hour since death fell in

love with you. It’s sharpening its sickle to stab it into your body. Run while you can . . . Do you hear me . . . ?” No, this face and its cobwebbed voice cannot be real. Sara peeks through the fence and behind the stone wall and sees the figure of a hunchback midget dressed in clothes that seem to belong to centuries ago . . . She opens her mouth to ask:

What in the world do you want from me?

But her words choke in her throat. Petrified, she realizes that at this moment, any question and all the words in the world will seem absurd and meaningless. There appear to be no eyeballs in the round eye sockets on that face. They resemble two wells with moonlight reflecting on the dark water at their pit.

“What do you want with my eyes? Think of yourself. You will be killed . . . Do you understand? . . . Run! The fighting will start any minute now.”

The scuffle begins. The shouts of slogans and obscenities and the screams of boys and girls being beaten drown in the daily clamor of the city of eleven million.

We skip past this scene because it seems to have nothing to do with a love story. However, if you have paid attention, you will have noticed that I, with that notorious cunning of a writer, have described the scuffle between the police and the students in such a way that I cannot be accused of political bias.

If you ask me who I am, I will say:

I am an Iranian writer tired of writing dark and bitter stories, stories populated by ghosts and dead narrators with predictable endings of death and destruction. I am a writer who at the threshold of fifty has understood that the purportedly real world around us has enough death and destruction and sorrow, and that I did not have the right to add even more defeat and hopelessness to it with my stories. In my stories and novels there are men whom I have created with a body and romantic valor that I do not possess. Similarly, there are women whose bodies and personalities I have reproduced from the body and soul of the woman whom I have longingly seen in my dreams—although I have never had the sincerity to give this fantasy woman a permanent face so that I don’t confuse her with certain real women. Between you and me, I have on occasion even cheated on this fantasy woman and imagined and written of her blond hair as black, and once as auburn. At any rate, I hate myself for sending characters that I like, that I have scrupulously created word by word, toward darkness or bloody death at the end of my stories, like Dr. Frankenstein.

For these reasons, and for reasons that like other writers I will probably discover later, I, with all my being, want to write a love story. The love story of a girl who has never seen the man who has been in love with her for a year and whom she loves very much. A story with an ending that is a gateway to light. A story that, although it does not have a happy ending like romantic Hollywood movies, still has an ending that will not make my reader afraid of falling in love. And, of course, a story that cannot be labeled as political. My dilemma is that I want to publish my love story in my homeland . . . Unlike in many countries around the world, writing and publishing a love story in my beloved Iran are not easy tasks. Following the victory of one of our last revolutions—during which our shouts for freedom, with the assistance of Western media, deafened the universe— to make up for twenty- five hundred years of dictatorial rule by kings, an Islamic constitution was written. This new constitution allows the printing and publishing of any and all books and journals and strictly prohibits their censorship and inspection. Unfortunately, however, our constitution makes no mention of these books and publications being allowed to freely leave the print shop.

In the early days following the revolution, after a book had been printed, its publisher had to present three copies of it to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to receive a permit for it to be shipped out of the print shop and to be distributed. However, if the ministry deemed the book to be corruptive, the printed copies would remain imprisoned in the print shop’s dark storage, and its publisher, in addition to having paid printing costs, either would have to pay storage costs, too, or would have to recycle the books into cardboard. This system had driven many publishers to the brink of bankruptcy.

In more recent years, to limit their financial risk and for books not to remain in storage houses for years and grow moldy waiting for an exit permit, based on a semiverbal, semiformal agreement, prior to actually printing a book, the independent Iranian publisher will voluntarily, with his own two hands and two feet, deliver three copies of the manuscript prepared with the latest typesetting and page design software to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to receive a permit before the book is actually printed.

In a particular department at this ministry, a man with the alias Porfiry Petrovich (yes, the detective in charge of solving Raskolnikov’s murders) is responsible for carefully reading books, in particular novels and shortstory collections, and especially love stories. He underlines every word, every sentence, every paragraph, or even every page that is indecent and that endangers public morality and the time- honored values of society. If there are too many such underlines, the book will likely be considered unworthy of print; if there are not that many, the publisher and the writer will be informed that they must simply revise certain words or sentences. For Mr. Petrovich this job is not just a vocation; it is a moral and religious responsibility. In other words, a holy profession. He must not allow immoral and corruptive words and phrases to appear before the eyes of simple and innocent people, especially the youth, and pollute their pure minds. Sometimes he even tells himself:

“Look here, man! If one word or phrase escapes your pen and provokes a young person, you will share in his sin, or, worse, you will be just as guilty as those depraved people who produce pornographic films and photos and illegally distribute them among the public.”

From his perspective, writers are generally devious, immoral, and faithless people, some of whom are directly or indirectly agents of Zionism and American imperialism, and they try to deceive him with their tricks and ploys. Given his profound sense of responsibility, while he reads the typeset manuscripts, Mr. Petrovich’s heart beats wildly. As he advances page by page, slowly the words begin to make strange movements before his eyes. In his mind, amid the echoes of the words, he hears mysterious whisperings that put him on his guard. Suspicious, he goes back a few pages and reads more carefully.His face begins to perspire, and his fingers start to tremble as they turn the pages. The more he pays attention, the more devious the criminal words become. They move around; the sentences intertwine. Implicit expressions, explicit expressions, innuendos, and connotations concealed in shadows begin to parade around in his head and create an uproar. He sees that some motherfucking words are lending letters to one another to create vulgar words or raunchy images. The sound of the pages turning resembles the sound of a guillotine blade falling. Mr. Petrovich hears the hue and cry of the words explode in his ears. He yells:

“Shut the hell up!”

From the Hardcover edition.

In the air of Tehran, the scent of spring blossoms, carbon monoxide, and the perfumes and poisons of the tales of One Thousand and

One Nights, sway on top of each other, they whisper together. The city drifts in time.

In front of the main entrance of Tehran University, on Liberty Street, a crowd of students is gathered in political protest. With their fists raised they shout, “Death to captivity!” Across the street, members of the Party of God, with clenched fists and perhaps chains and brass knuckles in their pockets, shout “Death to the Liberal . . .”

The antiriot police, armed with the most sophisticated paraphernalia, including stun batons purchased from the West, stand facing the students. Both groups try, before they come to blows, to triumph over their opponents by shouting even louder. Drops of sweat ooze from faces and specks of spit spew from mouths. Fists, before pounding on heads, rise without miracle toward the sky.

It is perhaps because of these fists that from the sacred sky of Iran no miracle ever descends. Since one hundred and one years ago—when the first revolution for democracy triumphed in Iran—fists similar to these have risen toward the sky of a country with the greatest number of holy men, with the most prayers, tears, and religious lamentations; and today, I believe, the greatest pleas to God for speeding up the day of resurrection rise from Iran.

A short distance away, on the sidewalk, with her back to the steel fence lodged in the three- foot- tall stone wall surrounding Tehran University, stands a girl who, unlike most girls in the world but like most girls in Iran, is wearing a black headscarf and a long black coat as a coverall. She possesses a beauty common to all girls in love stories, a beauty that many girls around the world, and in Iran, who read these stories want to possess. If the ghosts of the thousands of poets who died a thousand years ago, seven hundred years ago, or four hundred years ago, and the spirit of those yet to be born—who, unlike the living, in the democracy of death amicably and tolerantly wander the streets of Tehran—see her large black eyes, they will liken them, as is customary of their poetry, to the sad eyes of a gazelle. An old simile for a pair of Oriental eyes that stole Lord Byron’s heart, and Arthur Rimbaud’s, too . . . But contrary to this clichéd simile, there is a mysterious look in this girl’s eyes. It is as if they possess the power to traverse time, the power to pass through the golden walls of harems or perhaps the firewalls of Web sites and Internet filters.

But the girl does not know that in precisely seven minutes and seven seconds, at the height of the clash between the students, the police, and the members of the Party of God, in the chaos of attacks and escapes, she will be knocked into with great force, she will fall back, her head will hit against a cement edge, and her sad Oriental eyes will forever close . . .

The girl attracts the attention of mysterious people who during political demonstrations in Iran monitor the scene from discreet corners and identify people. They point her out to one another. One of them, from a very professional angle, takes a photograph and films her. I know this girl is not a member of any political party, but she is timidly holding a sign that reads:

DEATH TO FREEDOM, DEATH TO CAPTIVITY

It is a strange slogan that I don’t believe has ever been seen or heard under the rule of any dictatorial, Communist, populist, or even so- called liberal regime. And I don’t believe it will ever be heard under the rule of any future regimes that for now remain nameless.

When they pause to catch their breath in between shouting their slogans, the students seeking freedom and democracy point to the girl and her sign and ask, “Who in the world is she? What is she trying to say?”

The more experienced students, old hands at political protests, respond:

“Completely ignore her. She’s an infiltrator. The Party of God has paid her to create distrust and division among us. To defuse the conspiracy,

just act as though she doesn’t exist.”

On the opposite side, the fanatic members of the Party of God also point to the girl and ask, “What’s that prissy girl trying to say over there?”

They hear from their leaders:

“The lewd hussy is one of those Communists who have recently come back to life. Their Big Brother in Russia is gaining strength again . . . but the pathetic slobs only have a handful of members in their party. This is how they hope to attract attention . . . Just ignore her. Act as though she doesn’t exist.”

With their wireless radios, the secret police pass along the girl’s location and ask, “What does this mean? We have no instructions for such cases. What should we do with her?” And they receive instructions:

“Watch her with extreme vigilance and caution. This is most definitely a new conspiracy and a new plot for a velvet revolution orchestrated by American imperialism . . . Keep her under surveillance but do not let her suspect anything. Let her think she doesn’t exist.”

Nameless shades of rage and hatred, voiceless cries of blood and hope and darkness, hang in the air. From one direction, meaning Anatole France Avenue, and from the other direction, meaning Revolution Circle, the police have blocked all car and pedestrian traffic to this section of Liberty Street. In Revolution Circle, hundreds of cars are logjammed, anxious and overwrought drivers blow their horns, and amid the cars curious people stand peering toward Tehran University. It was right here that more than a quarter century ago, on a cloudy winter day, the people of Tehran for the last time dragged down the metal statue of the Shah sitting astride a horse. Of course in those days, when it came to dragging down metal statues of dictators, American tanks sided with the world’s dictators.

The student protesters, aware that they are about to be attacked, break into a heartrending anthem:

My fellow schoolmate,

you are with me and beside me,

. . . you are my tear and my sigh,

. . . the scars of the lashes of tyranny rest on our bodies,

our uncultured wasteland, all its wild plants weeds,

be it good, be it bad,

dead are the souls of its people,

our hands must tear down these curtains,

who other than you and I can cure our pain . . .

In the lyrics and melody of this anthem lies an age- old Iranian sorrow that brings tears to the girl’s eyes . . . She raises her sign even higher. From behind the veil of her tears, the world is transformed into undulating buildings, severed shadows, and rippling reflections on water . . . The young girl’s isolation and her fear of strangers heighten. She looks up to find some solace in the blue of the sky. She sees a winged horse that like a white cloud, ignoring the people below, flies by. Terrified, she sees flames rising from the horse’s back. The blazing horse disappears behind a high- rise. The girl waits, but the horse does not reappear . . .

Then she imagines that in the midst of the shouts of anger and spite, a muffled voice is calling her name.

“Sara . . . ! Sara . . . !”

The girl wipes away her tears and looks around. There are people and shadows moving in every direction. It seems they are afraid of coming close to her.

“Dimwit . . . ! Dimwit . . . ! I’m talking to you!”

The voice bears the same chill and odor that gust out of a refrigerator that has not been opened in a month. The girl looks behind her. A

dark face, neckless and torsoless, is suspended in the air. Two of the steel bars in the green fence surrounding Tehran University that have broken out of the stone wall have sectioned the face in three . . . She thinks this face belongs to one of those sprites her grandmother said have parties in the city’s public bathhouses at night and that the only way to tell them apart from humans is by their hoofed feet . . .

“Hey! Dimwit! Get rid of that sign and escape! I’m talking to you . . . !”

Again the girl looks behind her. She sees that same fluid dark face on the other side of the fence. She thinks perhaps someone is squatting

down behind the wall and has lifted his head up to the fence.

“Hey! Daydreamer, go home! . . . Today death has it in for you. Go home! . . . Do you understand? It’s been half an hour since death fell in

love with you. It’s sharpening its sickle to stab it into your body. Run while you can . . . Do you hear me . . . ?” No, this face and its cobwebbed voice cannot be real. Sara peeks through the fence and behind the stone wall and sees the figure of a hunchback midget dressed in clothes that seem to belong to centuries ago . . . She opens her mouth to ask:

What in the world do you want from me?

But her words choke in her throat. Petrified, she realizes that at this moment, any question and all the words in the world will seem absurd and meaningless. There appear to be no eyeballs in the round eye sockets on that face. They resemble two wells with moonlight reflecting on the dark water at their pit.

“What do you want with my eyes? Think of yourself. You will be killed . . . Do you understand? . . . Run! The fighting will start any minute now.”

The scuffle begins. The shouts of slogans and obscenities and the screams of boys and girls being beaten drown in the daily clamor of the city of eleven million.

We skip past this scene because it seems to have nothing to do with a love story. However, if you have paid attention, you will have noticed that I, with that notorious cunning of a writer, have described the scuffle between the police and the students in such a way that I cannot be accused of political bias.

If you ask me who I am, I will say:

I am an Iranian writer tired of writing dark and bitter stories, stories populated by ghosts and dead narrators with predictable endings of death and destruction. I am a writer who at the threshold of fifty has understood that the purportedly real world around us has enough death and destruction and sorrow, and that I did not have the right to add even more defeat and hopelessness to it with my stories. In my stories and novels there are men whom I have created with a body and romantic valor that I do not possess. Similarly, there are women whose bodies and personalities I have reproduced from the body and soul of the woman whom I have longingly seen in my dreams—although I have never had the sincerity to give this fantasy woman a permanent face so that I don’t confuse her with certain real women. Between you and me, I have on occasion even cheated on this fantasy woman and imagined and written of her blond hair as black, and once as auburn. At any rate, I hate myself for sending characters that I like, that I have scrupulously created word by word, toward darkness or bloody death at the end of my stories, like Dr. Frankenstein.

For these reasons, and for reasons that like other writers I will probably discover later, I, with all my being, want to write a love story. The love story of a girl who has never seen the man who has been in love with her for a year and whom she loves very much. A story with an ending that is a gateway to light. A story that, although it does not have a happy ending like romantic Hollywood movies, still has an ending that will not make my reader afraid of falling in love. And, of course, a story that cannot be labeled as political. My dilemma is that I want to publish my love story in my homeland . . . Unlike in many countries around the world, writing and publishing a love story in my beloved Iran are not easy tasks. Following the victory of one of our last revolutions—during which our shouts for freedom, with the assistance of Western media, deafened the universe— to make up for twenty- five hundred years of dictatorial rule by kings, an Islamic constitution was written. This new constitution allows the printing and publishing of any and all books and journals and strictly prohibits their censorship and inspection. Unfortunately, however, our constitution makes no mention of these books and publications being allowed to freely leave the print shop.

In the early days following the revolution, after a book had been printed, its publisher had to present three copies of it to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to receive a permit for it to be shipped out of the print shop and to be distributed. However, if the ministry deemed the book to be corruptive, the printed copies would remain imprisoned in the print shop’s dark storage, and its publisher, in addition to having paid printing costs, either would have to pay storage costs, too, or would have to recycle the books into cardboard. This system had driven many publishers to the brink of bankruptcy.

In more recent years, to limit their financial risk and for books not to remain in storage houses for years and grow moldy waiting for an exit permit, based on a semiverbal, semiformal agreement, prior to actually printing a book, the independent Iranian publisher will voluntarily, with his own two hands and two feet, deliver three copies of the manuscript prepared with the latest typesetting and page design software to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to receive a permit before the book is actually printed.

In a particular department at this ministry, a man with the alias Porfiry Petrovich (yes, the detective in charge of solving Raskolnikov’s murders) is responsible for carefully reading books, in particular novels and shortstory collections, and especially love stories. He underlines every word, every sentence, every paragraph, or even every page that is indecent and that endangers public morality and the time- honored values of society. If there are too many such underlines, the book will likely be considered unworthy of print; if there are not that many, the publisher and the writer will be informed that they must simply revise certain words or sentences. For Mr. Petrovich this job is not just a vocation; it is a moral and religious responsibility. In other words, a holy profession. He must not allow immoral and corruptive words and phrases to appear before the eyes of simple and innocent people, especially the youth, and pollute their pure minds. Sometimes he even tells himself:

“Look here, man! If one word or phrase escapes your pen and provokes a young person, you will share in his sin, or, worse, you will be just as guilty as those depraved people who produce pornographic films and photos and illegally distribute them among the public.”

From his perspective, writers are generally devious, immoral, and faithless people, some of whom are directly or indirectly agents of Zionism and American imperialism, and they try to deceive him with their tricks and ploys. Given his profound sense of responsibility, while he reads the typeset manuscripts, Mr. Petrovich’s heart beats wildly. As he advances page by page, slowly the words begin to make strange movements before his eyes. In his mind, amid the echoes of the words, he hears mysterious whisperings that put him on his guard. Suspicious, he goes back a few pages and reads more carefully.His face begins to perspire, and his fingers start to tremble as they turn the pages. The more he pays attention, the more devious the criminal words become. They move around; the sentences intertwine. Implicit expressions, explicit expressions, innuendos, and connotations concealed in shadows begin to parade around in his head and create an uproar. He sees that some motherfucking words are lending letters to one another to create vulgar words or raunchy images. The sound of the pages turning resembles the sound of a guillotine blade falling. Mr. Petrovich hears the hue and cry of the words explode in his ears. He yells:

“Shut the hell up!”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

One of the Best Debuts of 2009 — NPR

A New Yorker Best Book of the Year

“Exciting. . . . Powerful. . . . Mandanipour’s writing is exuberant, bonhomous, clever, profuse with puns and literary-political references.”

—James Wood, The New Yorker

“A clever Rubik’s Cube of a story, [and] a haunting portrait of life in the Islamic Republic of Iran. . . . An Escher-like meditation on the interplay of life and art, reality and fiction. . . . At its best, Censoring an Iranian Love Story becomes a Kundera-like rumination on philosophy and politics [that] playfully investigates the possibilities and limits of storytelling.”

—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“A love story that is convincingly, achingly impossible in a place where men and women cannot even look at each other in public. The effect (as every good Victorian understood) is deliriously sensual prose. . . . Mandanipour has triumphed.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Wry, playful. . . . Reminiscent of Milan Kundera, this is a lively account of life and letters in contemporary Iran.”

—Financial Times

“In this brilliantly conceived and cleverly written novel, characters and author together and separately act and write with sly purpose, disguising and disavowing their subversive ends—to live, love, and create in today’s repressive Iranian society.”

—The Boston Globe

“Devious and engaging. . . . A droll, even cheerful portrait of totalitarian craziness.”

—Bloomberg News

“Not your typical love story. . . . A meditation on culture, modern Iran, and the power of what is left out. . . . By the end of this witty, hyper-intelligent riff on life under a repressive regime, the writer has demonstrated the mental and emotional contortions necessary to survive.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“Telling amorous tales in post-Islamic-revolution Iran is tricky, if not downright dangerous, but [Mandanipour] is up to the task. . . . And as much as humor dominates the book, it quietly gets at something else—the omnipotence of tyranny.”

—The Miami Herald

“A very special novel—a passionate, inventive and humorous exposure of the stupidity and cruelty of a society ruled by fear.”

—The Times (London)

“Neither sentimental nor nostalgic, romanticized nor demonized. Looking at his country and its inhabitants through a fiction writer’s authentic spectacles, Mandanipour has written a novel that is witty, smart, funny, and honest. It is an important book for our times.”

—Rabih Alameddine, author of The Hakawati

“A brilliant novel about the complexities of writing and publishing in Iran. It will help to further understanding of the frustrating and sometimes perilous situation of the book industry in a country where copyright is not respected, where writers struggle desperately to publish and can be jailed simply for exercising their imaginations.”

—The Guardian (London)

“Anything but traditional. . . . A Farsi Fahrenheit 451, written by a postmodern Beckett. . . . In this Iranian setting, love comes not through happy endings but the unwritten text.”

—Chattanooga Times Free Press (Tennessee)

“Rich and riveting. . . . Reminiscent of Mario Vargas Llosa’s Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter and Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller. . . . [Mandanipour has] the potential to create a genre of Persian literature that could breach the gap in literary sensibilities that separates readers from vastly different traditions.”

—The Irish Times

“Filled with marvels and revolutions, political absurdity, and cinematic exploration, Censoring an Iranian Love Story is much more than a fractured love story. It’s a conversation with art, tyranny, and morality, a syncopated meditation on popular culture and ancient history. Shahriar Mandanipour’s wonderful, digressive novel shimmers with the power of the unwritten, the suggested, and the excised. . . . An exciting and original work—a beautiful novel.”

—Diana Abu-Jaber, author of Crescent

“The ancient poets conjured eroticism in terms of flowers and ripe fruits, but how can lovers express themselves in modern Iran? This is Mandanipour’s question as he searches to unite his smitten characters—characters who, unnervingly, seem to have ideas of their own. . . . This important, timely novel is sharp, playful and zesty with life.”

—Daily Mail (London)

“A powerful, provocative and timely novel.”

—The Observer (London)

“I absolutely loved Censoring an Iranian Love Story. Insightful and sensual, humorous and sly, allegorical and literary, it is an endless pleasure: a celebration of love and the written word from a part of the world where both still matter.”

—Gary Shteyngart, author of Absurdistan

A New Yorker Best Book of the Year

“Exciting. . . . Powerful. . . . Mandanipour’s writing is exuberant, bonhomous, clever, profuse with puns and literary-political references.”

—James Wood, The New Yorker

“A clever Rubik’s Cube of a story, [and] a haunting portrait of life in the Islamic Republic of Iran. . . . An Escher-like meditation on the interplay of life and art, reality and fiction. . . . At its best, Censoring an Iranian Love Story becomes a Kundera-like rumination on philosophy and politics [that] playfully investigates the possibilities and limits of storytelling.”

—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“A love story that is convincingly, achingly impossible in a place where men and women cannot even look at each other in public. The effect (as every good Victorian understood) is deliriously sensual prose. . . . Mandanipour has triumphed.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Wry, playful. . . . Reminiscent of Milan Kundera, this is a lively account of life and letters in contemporary Iran.”

—Financial Times

“In this brilliantly conceived and cleverly written novel, characters and author together and separately act and write with sly purpose, disguising and disavowing their subversive ends—to live, love, and create in today’s repressive Iranian society.”

—The Boston Globe

“Devious and engaging. . . . A droll, even cheerful portrait of totalitarian craziness.”

—Bloomberg News

“Not your typical love story. . . . A meditation on culture, modern Iran, and the power of what is left out. . . . By the end of this witty, hyper-intelligent riff on life under a repressive regime, the writer has demonstrated the mental and emotional contortions necessary to survive.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“Telling amorous tales in post-Islamic-revolution Iran is tricky, if not downright dangerous, but [Mandanipour] is up to the task. . . . And as much as humor dominates the book, it quietly gets at something else—the omnipotence of tyranny.”

—The Miami Herald

“A very special novel—a passionate, inventive and humorous exposure of the stupidity and cruelty of a society ruled by fear.”

—The Times (London)

“Neither sentimental nor nostalgic, romanticized nor demonized. Looking at his country and its inhabitants through a fiction writer’s authentic spectacles, Mandanipour has written a novel that is witty, smart, funny, and honest. It is an important book for our times.”

—Rabih Alameddine, author of The Hakawati

“A brilliant novel about the complexities of writing and publishing in Iran. It will help to further understanding of the frustrating and sometimes perilous situation of the book industry in a country where copyright is not respected, where writers struggle desperately to publish and can be jailed simply for exercising their imaginations.”

—The Guardian (London)

“Anything but traditional. . . . A Farsi Fahrenheit 451, written by a postmodern Beckett. . . . In this Iranian setting, love comes not through happy endings but the unwritten text.”

—Chattanooga Times Free Press (Tennessee)

“Rich and riveting. . . . Reminiscent of Mario Vargas Llosa’s Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter and Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller. . . . [Mandanipour has] the potential to create a genre of Persian literature that could breach the gap in literary sensibilities that separates readers from vastly different traditions.”

—The Irish Times

“Filled with marvels and revolutions, political absurdity, and cinematic exploration, Censoring an Iranian Love Story is much more than a fractured love story. It’s a conversation with art, tyranny, and morality, a syncopated meditation on popular culture and ancient history. Shahriar Mandanipour’s wonderful, digressive novel shimmers with the power of the unwritten, the suggested, and the excised. . . . An exciting and original work—a beautiful novel.”

—Diana Abu-Jaber, author of Crescent

“The ancient poets conjured eroticism in terms of flowers and ripe fruits, but how can lovers express themselves in modern Iran? This is Mandanipour’s question as he searches to unite his smitten characters—characters who, unnervingly, seem to have ideas of their own. . . . This important, timely novel is sharp, playful and zesty with life.”

—Daily Mail (London)

“A powerful, provocative and timely novel.”

—The Observer (London)

“I absolutely loved Censoring an Iranian Love Story. Insightful and sensual, humorous and sly, allegorical and literary, it is an endless pleasure: a celebration of love and the written word from a part of the world where both still matter.”

—Gary Shteyngart, author of Absurdistan

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

* An exciting novel that easily bears comparison to Milan Kundera's early writing. * A wonderfully accessible literary novel, that draws on Iran's rich literary heritage but which always remains engaging and very readable.

* An exciting novel that easily bears comparison to Milan Kundera's early writing. * A wonderfully accessible literary novel, that draws on Iran's rich literary heritage but which always remains engaging and very readable.