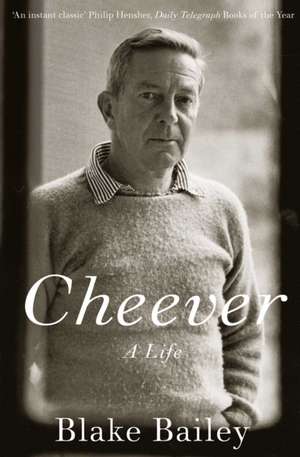

Cheever

Autor Blake Baileyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 17 dec 2015

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 123.81 lei 43-57 zile | |

| PICADOR – 17 dec 2015 | 123.81 lei 43-57 zile | |

| Vintage Books USA – 28 feb 2010 | 156.48 lei 43-57 zile |

Preț: 123.81 lei

Preț vechi: 136.98 lei

-10% Nou

Puncte Express: 186

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.69€ • 24.65$ • 19.56£

23.69€ • 24.65$ • 19.56£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 14-28 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781509821211

ISBN-10: 150982121X

Pagini: 786

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 46 mm

Greutate: 1.31 kg

Editura: PICADOR

ISBN-10: 150982121X

Pagini: 786

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 46 mm

Greutate: 1.31 kg

Editura: PICADOR

Notă biografică

Blake Bailey

Extras

Chapter One

1637–1912

Many skeletons in family closet,” Leander Wapshot wrote in his diary. “Dark secrets, mostly carnal.” Even at the height of his success, Cheever never quite lost the fear that he’d “end up cold, alone, dishonored, forgotten by [his] children, an old man approaching death without a companion.” This, he sensed, was the fate of his “accursed” family—or at least of its men, who for three generations (at least) had seemed “bound to a drunken and tragic destiny.” There was his paternal grandfather, Aaron, rumored to have committed suicide in a bleak furnished room on Charles Street in Boston, a disgrace too awful to mention. One night, as a young man, Cheever had sat by a fire drinking whiskey with his father, Frederick, while a nor’easter raged outside. “We were swapping dirty stories,” he recalled; “the feeling was intimate, and I felt that this was the time when I could bring up the subject. ‘Father, would you tell me something about your father?’ ‘No!’ And that was that.” By then Cheever’s father was also poor and forsaken, living alone in an old family farmhouse on the South Shore, his only friend “a half-wit who lived up the road.” As for Cheever’s brother, he too would become drunken and poor, spending his last days in a subsidized retirement village in Scituate. No wonder Cheever sometimes felt an affinity to characters in Ibsen’s Ghosts.

Despite such ignominy, Cheever took pride in his fine old family name, and when he wasn’t making light of the matter, he took pains to impress this on his children. “Remember you are a Cheever,” he’d tell his younger son, whenever the boy showed signs of an unseemly fragility. Some allusion was implicit, perhaps, to the first Cheever in America, Ezekiel, headmaster of the Boston Latin School from 1671 to 1708 and author of Accidence: A Short Introduction to the Latin Tongue, the standard text in American schools for a century or more. New England’s greatest schoolmaster, Ezekiel Cheever was even more renowned for his piety—“his untiring abjuration of the Devil,” as Cotton Mather put it in his eulogy. One aspect of Ezekiel’s piety was a stern distaste for periwigs, which he was known to yank from foppish heads and fling out windows. “The welfare of the commonwealth was always upon the conscience of Ezekiel Cheever,” said Judge Sewall, “and he abominated periwigs.” John Cheever was fond of pointing out that the abomination of periwigs “is in the nature of literature,” and it seems he was taught to emulate such virtue on his father’s knee. “Old Zeke C.,” Frederick wrote his son in 1943, “didn’t fuss about painted walls—open plumbing, or electric lights, had no ping pong etc. Turned out sturdy men and women, who knew their three R’s, and the fear of God.” John paid tribute to his eminent forebear by giving the name Ezekiel to one of his black Labradors (to this day a bronze of the dog’s head sits beside the Cheever fireplace), as well as to the protagonist of Falconer. However, when an old friend mentioned seeing a plaque that commemorated Ezekiel’s house in Charlestown, Cheever replied, “Why tell me? I’m in no way even collaterally related to Ezekiel Cheever.”

Cheever named his first son after his great-grandfather Benjamin Hale Cheever, a “celebrated ship’s master” who sailed out of Newburyport to Canton and Calcutta for the lucrative China trade. Visitors to Cheever’s home in Ossining (particularly journalists) were often shown such maritime souvenirs as a set of Canton china and a framed Chinese fan—this while Cheever remarked in passing that his great-grandfather’s boots were on display in the Peabody Essex Museum, filled with authentic tea from the Boston Tea Party. In fact, it is Lot Cheever of Danvers (no known relation) whose tea-filled boots ended up at the museum; as for Benjamin, he was all of three years old when that particular bit of tea was plundered aboard the Dartmouth on December 16, 1773. Also, there’s some question whether Benjamin Hale (Sr.) was actually a ship’s captain: though he appears in the Newbury Vital Records as “Master” Cheever, there’s no mention of him in any of the maritime records; a “Mr. Benjamin Cheever” is mentioned, however, as the teacher of one Henry Pettingell (born 1793) at the Newbury North School, and “Master” might as well have meant schoolmaster. Unless there were two Benjamin Cheevers in the greater Newbury area at the time (both roughly the same age), this would appear to be John’s great-grandfather.

The ill-fated Aaron was the youngest of Benjamin’s twelve children, and it was actually he who had (“presumably”) brought back that ivory-laced fan from the Orient: “It has lain, broken, in the sewing box for as long as I can remember,” Cheever wrote in 1966, when he finally had the thing repaired and mounted under glass.

My reaction to the framed fan is violently contradictory. Ah yes, I say, my grandfather got it in China, this authenticating my glamorous New England background. My impulse, at the same time, is to smash and destroy the memento. The power a scrap of paper and a little ivory have over my heart. It is the familiar clash between my passionate wish to be honest and my passionate wish to possess a traditional past. I can, it seems, have both but not without a galling sense of conflict.

To be sure, it’s possible that Aaron had sailed to China and retrieved that fan—as his son Frederick pointed out, most young men of the era went out on at least one voyage “to make them grow”—but his future did not lie with the China trade, which was effectively killed by Jefferson’s Embargo Act and the War of 1812. By the time Aaron reached manhood, in the mid-nineteenth century, the New England economy was dominated by textile industries, and Aaron had moved his family to Lynn, Massachusetts, where he worked as a shoemaker. But he was not meant to prosper even in so humble a station, and may well have been among the twenty thousand shoe workers who lost their jobs in the Great Strike of 1860. In any event, the family returned to Newburyport a few years later and eventually sailed to Boston aboard the Harold Currier: “This, according to my father,” said Cheever, “was the last sailing ship to be made in the Newburyport yards and was towed to Boston to be outfitted. I don’t suppose that they had the money to get to Boston by any other means.”

Frederick Lincoln Cheever was born on January 16, 1865, the younger (by eleven years) of Aaron and Sarah’s two sons. One of Frederick’s last memories of his father was “playing dominoes with old gent” during the Great Boston Fire of 1872; the two watched a mob of looters, the merchants fleeing their stores. The financial panic of 1873 followed, in the midst of which Aaron—driven by poverty and whatever other devils—apparently decided his family was better off without him. (“Mother, saintly old woman,” writes Leander Wapshot. “God bless her! Never one to admit unhappiness or pain . . . Asked me to sit down. ‘Your father has abandoned us,’ she said. ‘He left me a note. I burned it in the fire.’ ”) After Aaron’s departure, his wife seems to have run a boarding house to support her children, or so his grandson suspected (“If this were so I think I wouldn’t have been told”), though Aaron’s fate was unknown except by innuendo. As it happens, the death certificate indicates that Aaron Waters Cheever died in 1882 of “alcohol & opium—del[irium] tremens”; his last address was 111 Chambers (rather than Charles) Street, part of a shabby immigrant quarter that was razed long ago by urban renewal.

According to family legend, Sarah Cheever was notified by police of her husband’s death and arranged for his burial in stoic solitude, without a word to her son Frederick until after she’d served him supper that night. Among the few possessions she found in his squalid lodgings was a copy of Shakespeare’s plays, which came to the attention of a young John Cheever some fifty years later, at a time when he himself was all but starving to death in a Greenwich Village rooming house. Noting that “most of the speeches on human ingratitude were underscored,” Cheever wrote an early story titled “Homage to Shakespeare” that speculates on the cause of his grandfather’s downfall: “[Shakespeare’s] plays seemed to light and distinguish his character and his past. What might have been defined as failure and profligacy towered like something kingly and tragic.” As a tribute to kindred nobility, the narrator’s grandfather (so described in the story) chooses “Coriolanus” for his older son William’s middle name, rather as Aaron had named his older son—John Cheever’s uncle—William Hamlet Cheever.

When asked how he came to keep a journal, Cheever explained it as a typical occupation of a “seafaring family”: “They always begin, as most journals do, with the weather, prevailing winds, ruffles of the sails. They also include affairs, temptations, condemnations, libel, and occasionally, obscenities.” These last attributes were certainly characteristic of Cheever’s own journal, though one can only imagine what other men in his family were apt to write; the few pages his father left behind were more in the nature of memoir notes, benign enough, some of them quoted almost verbatim in The Wapshot Chronicle as the laconic prose of Leander Wapshot: “Sturgeon in river then. About three feet long. All covered with knobs. Leap straight up in air and fall back in water.”* When Cheever first encountered these notes, he found them “antic, ungrammatical and . . . vulgar,” though later he came to admire the style as typical of a certain nautical New England mentality that “makes as little as possible of any event.”

During his hardscrabble youth, Frederick was often boarded out at a bake house owned by his uncle Thomas Butler in Newburyport, where he slept in the attic with a tame raven and relished the view from his window: “Grand sunsets after the daily thunder showers that came down the river from the White Mountains,” he recalled, with a lyric economy his son was right to admire. Life at the bake house was rarely dull, as Uncle Thomas was a good friend of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, and the house served as a station for the Underground Railroad. John Cheever often told of how pro-slavery copperheads had once dragged his great-uncle “at the tail of a cart” through the streets of Newburyport—though Cheever always saw fit to call this relative “Ebenezer” (a name he liked for its Yankee savor), and sometimes it was Ebenezer’s friend Villard who was dragged, or stoned as the case may be. At any rate, the story usually ended with an undaunted “Ebenezer” refusing a government contract to make pilot biscuits for Union sailors—and indeed, as Frederick wrote in his notes, “[Uncle Thomas] said [biscuits] not good enough for sailors of US to eat. Others did it made big coin.” John vastly improved that part of the story, too: “A competitor named Pierce,” he related in a letter, “then accepted the [biscuit] contract and founded a dynasty” that became Nabisco, no less—which, for the record, was founded by Adolphus Green (not Pierce) in 1898.

“Bill always good to me,” Frederick wrote of his much older brother, who apparently filled the paternal vacuum, if only for a while. Bill “called [him] down” when Frederick stepped out of line, and paid a friend—Johnny O’Toole at the Massachusetts Hotel (“Very tough joint”)—to give Frederick haircuts as needed. John Cheever always used his uncle’s more evocative middle name, Hamlet, when referring to this rather romantic figure: “An amateur boxer, darling of the sporting houses, captain of the volunteer fire department ball-team”— a man’s man, in short, who, like his namesake in The Wapshot Chronicle, went west for the Gold Rush. “[There] isn’t a king or a merchant prince in the whole world that I envy,” Hamlet writes his brother Leander in the novel, “for I always knew I was born to be a child of destiny and that I was never meant . . . to wring my living from detestable, low, degrading, mean and ordinary kinds of business.” By the time the real-life Hamlet arrived in California, however, the excitement of 1849 had faded considerably, and he later settled in Omaha, where he died “forgotten and disgraced”—or rather he died “at sea” and “was given to the ocean off Panama,” depending on which of his nephew’s stories one chooses to believe. Cheever invariably described his uncle as a “black-mouthed old wreck” or “monkey,” since their occasional meetings were not happy. “Uncle Bill, Halifax 1919,” John’s older brother noted beside a photograph of a prosaic-looking old man rowing his nephews around in a boat. “Bill Cheever came from Omaha for a visit—the only time I ever saw him. He wasn’t much fun.” A later meeting with John would prove even less fun.

With Hamlet seeking his fortune a continent away, it was necessary for young Frederick to help support the household. From the age of ten or so, he “never missed a day” selling newspapers before and after classes at the Phillips School, where he graduated at the head of his class on June 27, 1879, and was presented with a bouquet of flowers by the mayor of Boston. In later years he’d wistfully recall how the flowers wilted before he could take them home to his mother, and on that note his formal education ended: “Wanted to go to Boston Latin,” he wrote. “Had to work.” For so bookish a man (he spent much of his lonely dotage reading Shakespeare to his cat), the matter rankled, and he’d insist on sending his sons to good private schools while boasting—à la Leander (“Report card attached”)—of his own high marks as a boy.

For the next fifty years, Frederick Cheever worked in the shoe business, always bearing in mind the fate of his poor father, whose life was “made unbearable by lack of coin”: “The desire for money most lasting and universal passion,” he wrote for his own edification and perhaps that of his sons. “Desire ends only with life itself. Fame, love, all long forgotten.” While still in his teens, he worked at a factory in Lynn for six dollars a week (five of which went to room and board) in order to learn the business; a photograph from around this time shows a dapper youth with a trim little mustache, his features composed with a look of high purpose, though its subject had glossed, “Look like a poet. Attic hungry—Etc.” John Cheever would one day find among his father’s effects a copy of The Magician’s Own Handbook—a poignant artifact that brought to mind “a lonely young man reading Plutarch in a cold room and perfecting his magic tricks to make himself socially desirable and perhaps lovable.” In the meantime, once he turned twenty-one, Frederick began to spend almost half the year on the road selling shoes (“gosh writer has sat in a 1001 RR stations . . . ‘get the business’ or ‘get out’”), often bunking with strangers and hiding his valuables in his stockings, which he then wore to bed.

*The parallel passage in Frederick’s notes reads as follows: “On the way [from Newburyport to Amesbury via horsecar] you saw sturgeons leap out of river—they were 3–4 feet long—all covered with knobs.” One might add that, as Cheever suggests, his father was quite diligent about noting the weather—always, for instance, in the top right corner of the letters he wrote his son. Thus, from October 10, 1943: “Cold this am 45 [degrees] Big wind from East No. East. Heavy overcoat—woodfire and oil kitchen.”

From the Hardcover edition.

1637–1912

Many skeletons in family closet,” Leander Wapshot wrote in his diary. “Dark secrets, mostly carnal.” Even at the height of his success, Cheever never quite lost the fear that he’d “end up cold, alone, dishonored, forgotten by [his] children, an old man approaching death without a companion.” This, he sensed, was the fate of his “accursed” family—or at least of its men, who for three generations (at least) had seemed “bound to a drunken and tragic destiny.” There was his paternal grandfather, Aaron, rumored to have committed suicide in a bleak furnished room on Charles Street in Boston, a disgrace too awful to mention. One night, as a young man, Cheever had sat by a fire drinking whiskey with his father, Frederick, while a nor’easter raged outside. “We were swapping dirty stories,” he recalled; “the feeling was intimate, and I felt that this was the time when I could bring up the subject. ‘Father, would you tell me something about your father?’ ‘No!’ And that was that.” By then Cheever’s father was also poor and forsaken, living alone in an old family farmhouse on the South Shore, his only friend “a half-wit who lived up the road.” As for Cheever’s brother, he too would become drunken and poor, spending his last days in a subsidized retirement village in Scituate. No wonder Cheever sometimes felt an affinity to characters in Ibsen’s Ghosts.

Despite such ignominy, Cheever took pride in his fine old family name, and when he wasn’t making light of the matter, he took pains to impress this on his children. “Remember you are a Cheever,” he’d tell his younger son, whenever the boy showed signs of an unseemly fragility. Some allusion was implicit, perhaps, to the first Cheever in America, Ezekiel, headmaster of the Boston Latin School from 1671 to 1708 and author of Accidence: A Short Introduction to the Latin Tongue, the standard text in American schools for a century or more. New England’s greatest schoolmaster, Ezekiel Cheever was even more renowned for his piety—“his untiring abjuration of the Devil,” as Cotton Mather put it in his eulogy. One aspect of Ezekiel’s piety was a stern distaste for periwigs, which he was known to yank from foppish heads and fling out windows. “The welfare of the commonwealth was always upon the conscience of Ezekiel Cheever,” said Judge Sewall, “and he abominated periwigs.” John Cheever was fond of pointing out that the abomination of periwigs “is in the nature of literature,” and it seems he was taught to emulate such virtue on his father’s knee. “Old Zeke C.,” Frederick wrote his son in 1943, “didn’t fuss about painted walls—open plumbing, or electric lights, had no ping pong etc. Turned out sturdy men and women, who knew their three R’s, and the fear of God.” John paid tribute to his eminent forebear by giving the name Ezekiel to one of his black Labradors (to this day a bronze of the dog’s head sits beside the Cheever fireplace), as well as to the protagonist of Falconer. However, when an old friend mentioned seeing a plaque that commemorated Ezekiel’s house in Charlestown, Cheever replied, “Why tell me? I’m in no way even collaterally related to Ezekiel Cheever.”

Cheever named his first son after his great-grandfather Benjamin Hale Cheever, a “celebrated ship’s master” who sailed out of Newburyport to Canton and Calcutta for the lucrative China trade. Visitors to Cheever’s home in Ossining (particularly journalists) were often shown such maritime souvenirs as a set of Canton china and a framed Chinese fan—this while Cheever remarked in passing that his great-grandfather’s boots were on display in the Peabody Essex Museum, filled with authentic tea from the Boston Tea Party. In fact, it is Lot Cheever of Danvers (no known relation) whose tea-filled boots ended up at the museum; as for Benjamin, he was all of three years old when that particular bit of tea was plundered aboard the Dartmouth on December 16, 1773. Also, there’s some question whether Benjamin Hale (Sr.) was actually a ship’s captain: though he appears in the Newbury Vital Records as “Master” Cheever, there’s no mention of him in any of the maritime records; a “Mr. Benjamin Cheever” is mentioned, however, as the teacher of one Henry Pettingell (born 1793) at the Newbury North School, and “Master” might as well have meant schoolmaster. Unless there were two Benjamin Cheevers in the greater Newbury area at the time (both roughly the same age), this would appear to be John’s great-grandfather.

The ill-fated Aaron was the youngest of Benjamin’s twelve children, and it was actually he who had (“presumably”) brought back that ivory-laced fan from the Orient: “It has lain, broken, in the sewing box for as long as I can remember,” Cheever wrote in 1966, when he finally had the thing repaired and mounted under glass.

My reaction to the framed fan is violently contradictory. Ah yes, I say, my grandfather got it in China, this authenticating my glamorous New England background. My impulse, at the same time, is to smash and destroy the memento. The power a scrap of paper and a little ivory have over my heart. It is the familiar clash between my passionate wish to be honest and my passionate wish to possess a traditional past. I can, it seems, have both but not without a galling sense of conflict.

To be sure, it’s possible that Aaron had sailed to China and retrieved that fan—as his son Frederick pointed out, most young men of the era went out on at least one voyage “to make them grow”—but his future did not lie with the China trade, which was effectively killed by Jefferson’s Embargo Act and the War of 1812. By the time Aaron reached manhood, in the mid-nineteenth century, the New England economy was dominated by textile industries, and Aaron had moved his family to Lynn, Massachusetts, where he worked as a shoemaker. But he was not meant to prosper even in so humble a station, and may well have been among the twenty thousand shoe workers who lost their jobs in the Great Strike of 1860. In any event, the family returned to Newburyport a few years later and eventually sailed to Boston aboard the Harold Currier: “This, according to my father,” said Cheever, “was the last sailing ship to be made in the Newburyport yards and was towed to Boston to be outfitted. I don’t suppose that they had the money to get to Boston by any other means.”

Frederick Lincoln Cheever was born on January 16, 1865, the younger (by eleven years) of Aaron and Sarah’s two sons. One of Frederick’s last memories of his father was “playing dominoes with old gent” during the Great Boston Fire of 1872; the two watched a mob of looters, the merchants fleeing their stores. The financial panic of 1873 followed, in the midst of which Aaron—driven by poverty and whatever other devils—apparently decided his family was better off without him. (“Mother, saintly old woman,” writes Leander Wapshot. “God bless her! Never one to admit unhappiness or pain . . . Asked me to sit down. ‘Your father has abandoned us,’ she said. ‘He left me a note. I burned it in the fire.’ ”) After Aaron’s departure, his wife seems to have run a boarding house to support her children, or so his grandson suspected (“If this were so I think I wouldn’t have been told”), though Aaron’s fate was unknown except by innuendo. As it happens, the death certificate indicates that Aaron Waters Cheever died in 1882 of “alcohol & opium—del[irium] tremens”; his last address was 111 Chambers (rather than Charles) Street, part of a shabby immigrant quarter that was razed long ago by urban renewal.

According to family legend, Sarah Cheever was notified by police of her husband’s death and arranged for his burial in stoic solitude, without a word to her son Frederick until after she’d served him supper that night. Among the few possessions she found in his squalid lodgings was a copy of Shakespeare’s plays, which came to the attention of a young John Cheever some fifty years later, at a time when he himself was all but starving to death in a Greenwich Village rooming house. Noting that “most of the speeches on human ingratitude were underscored,” Cheever wrote an early story titled “Homage to Shakespeare” that speculates on the cause of his grandfather’s downfall: “[Shakespeare’s] plays seemed to light and distinguish his character and his past. What might have been defined as failure and profligacy towered like something kingly and tragic.” As a tribute to kindred nobility, the narrator’s grandfather (so described in the story) chooses “Coriolanus” for his older son William’s middle name, rather as Aaron had named his older son—John Cheever’s uncle—William Hamlet Cheever.

When asked how he came to keep a journal, Cheever explained it as a typical occupation of a “seafaring family”: “They always begin, as most journals do, with the weather, prevailing winds, ruffles of the sails. They also include affairs, temptations, condemnations, libel, and occasionally, obscenities.” These last attributes were certainly characteristic of Cheever’s own journal, though one can only imagine what other men in his family were apt to write; the few pages his father left behind were more in the nature of memoir notes, benign enough, some of them quoted almost verbatim in The Wapshot Chronicle as the laconic prose of Leander Wapshot: “Sturgeon in river then. About three feet long. All covered with knobs. Leap straight up in air and fall back in water.”* When Cheever first encountered these notes, he found them “antic, ungrammatical and . . . vulgar,” though later he came to admire the style as typical of a certain nautical New England mentality that “makes as little as possible of any event.”

During his hardscrabble youth, Frederick was often boarded out at a bake house owned by his uncle Thomas Butler in Newburyport, where he slept in the attic with a tame raven and relished the view from his window: “Grand sunsets after the daily thunder showers that came down the river from the White Mountains,” he recalled, with a lyric economy his son was right to admire. Life at the bake house was rarely dull, as Uncle Thomas was a good friend of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, and the house served as a station for the Underground Railroad. John Cheever often told of how pro-slavery copperheads had once dragged his great-uncle “at the tail of a cart” through the streets of Newburyport—though Cheever always saw fit to call this relative “Ebenezer” (a name he liked for its Yankee savor), and sometimes it was Ebenezer’s friend Villard who was dragged, or stoned as the case may be. At any rate, the story usually ended with an undaunted “Ebenezer” refusing a government contract to make pilot biscuits for Union sailors—and indeed, as Frederick wrote in his notes, “[Uncle Thomas] said [biscuits] not good enough for sailors of US to eat. Others did it made big coin.” John vastly improved that part of the story, too: “A competitor named Pierce,” he related in a letter, “then accepted the [biscuit] contract and founded a dynasty” that became Nabisco, no less—which, for the record, was founded by Adolphus Green (not Pierce) in 1898.

“Bill always good to me,” Frederick wrote of his much older brother, who apparently filled the paternal vacuum, if only for a while. Bill “called [him] down” when Frederick stepped out of line, and paid a friend—Johnny O’Toole at the Massachusetts Hotel (“Very tough joint”)—to give Frederick haircuts as needed. John Cheever always used his uncle’s more evocative middle name, Hamlet, when referring to this rather romantic figure: “An amateur boxer, darling of the sporting houses, captain of the volunteer fire department ball-team”— a man’s man, in short, who, like his namesake in The Wapshot Chronicle, went west for the Gold Rush. “[There] isn’t a king or a merchant prince in the whole world that I envy,” Hamlet writes his brother Leander in the novel, “for I always knew I was born to be a child of destiny and that I was never meant . . . to wring my living from detestable, low, degrading, mean and ordinary kinds of business.” By the time the real-life Hamlet arrived in California, however, the excitement of 1849 had faded considerably, and he later settled in Omaha, where he died “forgotten and disgraced”—or rather he died “at sea” and “was given to the ocean off Panama,” depending on which of his nephew’s stories one chooses to believe. Cheever invariably described his uncle as a “black-mouthed old wreck” or “monkey,” since their occasional meetings were not happy. “Uncle Bill, Halifax 1919,” John’s older brother noted beside a photograph of a prosaic-looking old man rowing his nephews around in a boat. “Bill Cheever came from Omaha for a visit—the only time I ever saw him. He wasn’t much fun.” A later meeting with John would prove even less fun.

With Hamlet seeking his fortune a continent away, it was necessary for young Frederick to help support the household. From the age of ten or so, he “never missed a day” selling newspapers before and after classes at the Phillips School, where he graduated at the head of his class on June 27, 1879, and was presented with a bouquet of flowers by the mayor of Boston. In later years he’d wistfully recall how the flowers wilted before he could take them home to his mother, and on that note his formal education ended: “Wanted to go to Boston Latin,” he wrote. “Had to work.” For so bookish a man (he spent much of his lonely dotage reading Shakespeare to his cat), the matter rankled, and he’d insist on sending his sons to good private schools while boasting—à la Leander (“Report card attached”)—of his own high marks as a boy.

For the next fifty years, Frederick Cheever worked in the shoe business, always bearing in mind the fate of his poor father, whose life was “made unbearable by lack of coin”: “The desire for money most lasting and universal passion,” he wrote for his own edification and perhaps that of his sons. “Desire ends only with life itself. Fame, love, all long forgotten.” While still in his teens, he worked at a factory in Lynn for six dollars a week (five of which went to room and board) in order to learn the business; a photograph from around this time shows a dapper youth with a trim little mustache, his features composed with a look of high purpose, though its subject had glossed, “Look like a poet. Attic hungry—Etc.” John Cheever would one day find among his father’s effects a copy of The Magician’s Own Handbook—a poignant artifact that brought to mind “a lonely young man reading Plutarch in a cold room and perfecting his magic tricks to make himself socially desirable and perhaps lovable.” In the meantime, once he turned twenty-one, Frederick began to spend almost half the year on the road selling shoes (“gosh writer has sat in a 1001 RR stations . . . ‘get the business’ or ‘get out’”), often bunking with strangers and hiding his valuables in his stockings, which he then wore to bed.

*The parallel passage in Frederick’s notes reads as follows: “On the way [from Newburyport to Amesbury via horsecar] you saw sturgeons leap out of river—they were 3–4 feet long—all covered with knobs.” One might add that, as Cheever suggests, his father was quite diligent about noting the weather—always, for instance, in the top right corner of the letters he wrote his son. Thus, from October 10, 1943: “Cold this am 45 [degrees] Big wind from East No. East. Heavy overcoat—woodfire and oil kitchen.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

A New York Times Notable Book and a Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, Time, Christian Science Monitor, Slate, Arizona Republic, and Kansas City Star Best Book of the Year

“A triumph of thorough research and unblinkered appraisal.”

—John Updike, The New Yorker

“A definitive, Dickensian rendering of a complete and complicated life, addictively readable and long overdue.”

—Bret Anthony Johnston, The New York Times

“Beautifully woven, deeply researched, and delightfully free of isms. . . . Here’s Cheever at the center of the storm.”

—Susan Salter Reynolds, Los Angeles Times

“Fascinating. . . . Bailey counter[s] both his subject’s soaring enthusiasms and paranoid forebodings with clear-eyed judgment.”

—David Propson, The Wall Street Journal

“Mesmerizing. . . . Every inch the record that Cheever deserves. . . . [Bailey] gives us remarkable access to one of the greatest writers of his time.”

—Vince Passaro, O, the Oprah Magazine

“So wise and serious, so human an account. . . . Even more eloquent and resourceful than Bailey’s celebrated biography of Richard Yates.”

—Geoffrey Wolff, The New York Times Book Review

“Sympathetic and deeply engaging. . . . This book is also a portrait of the twentieth century.”

—Jacob Molyneux, San Francisco Chronicle

“[Bailey’s] life of Cheever is an impressive, even a beautiful, achievement.”

—Algis Valiunas, Commentary

“[An] expansive, wonderfully written biography. . . . Unstinting. . . . Bracing. . . . To read Bailey on Cheever is to arrive at a much fuller appreciation of a deeply gifted chronicler of American life.”

—Matt Shaer, Christian Science Monitor

“A portrait of the man drawn judiciously but compellingly and in harrowing detail . . . . [A] fine biography.”

—Richard Lacayo, Time

“Elegant. . . An insightful, clear-eyed life of the man.”

—The Economist

“Surely definitive. . . . [Bailey] gets down his subject’s humorous staying power, even in the midst of spiritual turmoil.”

—William H. Pritchard, Boston Globe

“Masterful.”

—Nathan Heller, Slate

“Exceptional. . . . Along with sensitivity and dispassionate thoroughness, it’s his smooth blending of sources into a readable narrative that sets Bailey apart as a biographer.”

—Jeffrey Burke, Bloomberg News

“Exemplary. . . . Bailey has brought [Cheever’s] life into such eloquent relief that it’s easy to imagine Cheever, if only for a moment, finally feeling like someone understood him.”

—Gregg LaGambina, A. V. Club

“Definitive. . . . Judicious and nuanced. . . . Mr. Bailey’s research is impeccable and exhaustive—a mighty feat.”

—Adam Begley, The New York Observer

“A biography of monumental heft . . . that certifies Cheever’s enduring relevance.”

—James Wolcott, Vanity Fair

“Bailey’s thorough new biography completes the total revolution of our image of the man has undergone in the quarter century since his death.”

—Jonathan Dee, Harper’s

“Tremendous. . . . Magisterial. . . . Bailey [is] a great biographer, utterly dogged and indefatigable about telling details.”

—Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News

“Impressive. . . . Finely written. . . . Bailey has done a near-perfect job of making the connections between the man and his masterpieces.”

—Michael Upchurch, Seattle Times

“Fascinating . . . . Powerfully moving . . . . A brilliant example of literary biography at its best.”

—Doug Childers, Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Quite successfully sorts out the facts, masks and contradictions of this unique American life.”

—John Barron, Chicago Sun-Times

“The appearance of Bailey’s poised, thorough biography is both timely and corrective . . . Bailey presents his subject in all his contradictory fullness . . . Cheever: A Life succeeds by balancing insight, judgment, empathy, and clarity.”

—Floyd Skloot, Philadelphia Inquirer

“Bailey has achieved what I (along with many others) thought well-nigh impossible: an outstanding, exhaustive (but never exhausting), clear-eyed and evenhanded biography of Cheever and a literary triumph in its own right.”

—George W. Hunt, America

“Magnificent.”

—Maud Newton, Barnes and Noble Review

“A triumph of thorough research and unblinkered appraisal.”

—John Updike, The New Yorker

“A definitive, Dickensian rendering of a complete and complicated life, addictively readable and long overdue.”

—Bret Anthony Johnston, The New York Times

“Beautifully woven, deeply researched, and delightfully free of isms. . . . Here’s Cheever at the center of the storm.”

—Susan Salter Reynolds, Los Angeles Times

“Fascinating. . . . Bailey counter[s] both his subject’s soaring enthusiasms and paranoid forebodings with clear-eyed judgment.”

—David Propson, The Wall Street Journal

“Mesmerizing. . . . Every inch the record that Cheever deserves. . . . [Bailey] gives us remarkable access to one of the greatest writers of his time.”

—Vince Passaro, O, the Oprah Magazine

“So wise and serious, so human an account. . . . Even more eloquent and resourceful than Bailey’s celebrated biography of Richard Yates.”

—Geoffrey Wolff, The New York Times Book Review

“Sympathetic and deeply engaging. . . . This book is also a portrait of the twentieth century.”

—Jacob Molyneux, San Francisco Chronicle

“[Bailey’s] life of Cheever is an impressive, even a beautiful, achievement.”

—Algis Valiunas, Commentary

“[An] expansive, wonderfully written biography. . . . Unstinting. . . . Bracing. . . . To read Bailey on Cheever is to arrive at a much fuller appreciation of a deeply gifted chronicler of American life.”

—Matt Shaer, Christian Science Monitor

“A portrait of the man drawn judiciously but compellingly and in harrowing detail . . . . [A] fine biography.”

—Richard Lacayo, Time

“Elegant. . . An insightful, clear-eyed life of the man.”

—The Economist

“Surely definitive. . . . [Bailey] gets down his subject’s humorous staying power, even in the midst of spiritual turmoil.”

—William H. Pritchard, Boston Globe

“Masterful.”

—Nathan Heller, Slate

“Exceptional. . . . Along with sensitivity and dispassionate thoroughness, it’s his smooth blending of sources into a readable narrative that sets Bailey apart as a biographer.”

—Jeffrey Burke, Bloomberg News

“Exemplary. . . . Bailey has brought [Cheever’s] life into such eloquent relief that it’s easy to imagine Cheever, if only for a moment, finally feeling like someone understood him.”

—Gregg LaGambina, A. V. Club

“Definitive. . . . Judicious and nuanced. . . . Mr. Bailey’s research is impeccable and exhaustive—a mighty feat.”

—Adam Begley, The New York Observer

“A biography of monumental heft . . . that certifies Cheever’s enduring relevance.”

—James Wolcott, Vanity Fair

“Bailey’s thorough new biography completes the total revolution of our image of the man has undergone in the quarter century since his death.”

—Jonathan Dee, Harper’s

“Tremendous. . . . Magisterial. . . . Bailey [is] a great biographer, utterly dogged and indefatigable about telling details.”

—Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News

“Impressive. . . . Finely written. . . . Bailey has done a near-perfect job of making the connections between the man and his masterpieces.”

—Michael Upchurch, Seattle Times

“Fascinating . . . . Powerfully moving . . . . A brilliant example of literary biography at its best.”

—Doug Childers, Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Quite successfully sorts out the facts, masks and contradictions of this unique American life.”

—John Barron, Chicago Sun-Times

“The appearance of Bailey’s poised, thorough biography is both timely and corrective . . . Bailey presents his subject in all his contradictory fullness . . . Cheever: A Life succeeds by balancing insight, judgment, empathy, and clarity.”

—Floyd Skloot, Philadelphia Inquirer

“Bailey has achieved what I (along with many others) thought well-nigh impossible: an outstanding, exhaustive (but never exhausting), clear-eyed and evenhanded biography of Cheever and a literary triumph in its own right.”

—George W. Hunt, America

“Magnificent.”

—Maud Newton, Barnes and Noble Review