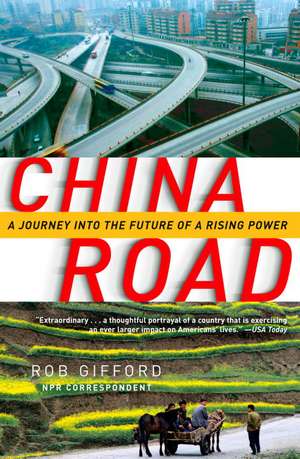

China Road: A Journey Into the Future of a Rising Power

Autor Rob Gifforden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2008

In this utterly surprising and deeply personal book, acclaimed National Public Radio reporter Rob Gifford, a fluent Mandarin speaker, takes the dramatic journey along Route 312 from its start in the boomtown of Shanghai to its end on the border with Kazakhstan. Gifford reveals the rich mosaic of modern Chinese life in all its contradictions, as he poses the crucial questions that all of us are asking about China: Will it really be the next global superpower? Is it as solid and as powerful as it looks from the outside? And who are the ordinary Chinese people, to whom the twenty-first century is supposed to belong?

Gifford is not alone on his journey. The largest migration in human history is taking place along highways such as Route 312, as tens of millions of people leave their homes in search of work. He sees signs of the booming urban economy everywhere, but he also uncovers many of the country’s frailties, and some of the deep-seated problems that could derail China’s rise.

The whole compelling adventure is told through the cast of colorful characters Gifford meets: garrulous talk-show hosts and ambitious yuppies, impoverished peasants and tragic prostitutes, cell-phone salesmen, AIDS patients, and Tibetan monks. He rides with members of a Shanghai jeep club, hitchhikes across the Gobi desert, and sings karaoke with migrant workers at truck stops along the way.

As he recounts his travels along Route 312, Rob Gifford gives a face to what has historically, for Westerners, been a faceless country and breathes life into a nation that is so often reduced to economic statistics. Finally, he sounds a warning that all is not well in the Chinese heartlands, that serious problems lie ahead, and that the future of the West has become inextricably linked with the fate of 1.3 billion Chinese people.

“Informative, delightful, and powerfully moving . . . Rob Gifford’s acute powers of observation, his sense of humor and adventure, and his determination to explore the wrenching dilemmas of China’s explosive development open readers’ eyes and reward their minds.”

–Robert A. Kapp, president, U.S.-China Business Council, 1994-2004

From the Hardcover edition.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 62.81 lei 6-8 săpt. | +43.47 lei 5-11 zile |

| Bloomsbury Publishing – iun 2008 | 62.81 lei 6-8 săpt. | +43.47 lei 5-11 zile |

| Random House Trade – 30 iun 2008 | 184.60 lei 38-44 zile |

Preț: 184.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 277

Preț estimativ în valută:

35.33€ • 38.39$ • 29.70£

35.33€ • 38.39$ • 29.70£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 17-23 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812975246

ISBN-10: 0812975243

Pagini: 322

Ilustrații: 16pp photo section, map

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812975243

Pagini: 322

Ilustrații: 16pp photo section, map

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Rob Gifford first went to China in 1987 as a twenty-year-old language student. He has spent much of the last twenty years studying and reporting there. From 1999 to 2005, he was the Beijing correspondent of National Public Radio, and he traveled all over China and the rest of Asia reporting for Morning Edition and All Things Considered. He is now NPR’s London bureau chief.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1. The Promised Land

The magnetic levitation train that links Shanghai’s gleaming new Pudong Airport with the center of the city glides out of the airport station and within about two minutes has reached 270 miles per hour. Billboards flash past, almost unreadable. Suspended magnetically along a track that runs some fifty feet above the ground, the train scythes toward the center of China’s most modern city. The landscape is surprisingly American—sprawling, low-rise, newly built. The gray bullet leans lazily to the left as it shoots over one of Pudong’s main freeways, past cavernous supermarkets and rows of polished new pink and white apartment blocks.

The maglev, as it is known, cost $1.2 billion to build and is the first commercially run train of its kind in the world.

Six weeks before reaching Starry Gorge and the Gobi Desert, I had arrived by plane in Shanghai from Beijing to start my three-thousand-mile road trip along Route 312. I’d been too busy to make many preparations and had only a faint idea of whom I might talk to when I got here.

Almost before the maglev’s twenty-mile journey has begun, it has ended. The train eases into the terminus, not far from the new jungle of high-rise buildings that make up downtown Shanghai. I look at my watch as I heave my backpack out onto the platform. “Bu cuo. Not bad.” I nod to the smartly dressed female ticket collector standing beside the door. “Eight minutes.”

“Seven minutes, twenty seconds,” she replies without smiling.

The streets outside the terminus are a cacophony of noise and motion. There is an intangible feel in Shanghai, an urgency, a hope and optimism that hangs in the air all around you from the minute you arrive. People are pushing forward, with their feet and in their heads, building a future, building a country, moving toward some distant, unseen goal.

I’ve chosen to stay at the slightly down-at-heel but gloriously historic Astor House Hotel, the first foreign hotel to be established in Shanghai, in 1846. The hotel sits at one end of the Bund, the city’s original main thoroughfare, which runs along the Huangpu River. The Bund has for more than 150 years been the interface between Shanghai and the arriving yang ren, or Ocean People, as foreigners have always been known.

The Astor House Hotel has witnessed the whole sweep of China’s emergence into the modern world, from English opium running in the 1840s through the tea dances of polite society in the 1920s to the excesses of Maoist China in the 1960s. The Art Deco ceilings are high, the creaky floorboards are original, and you could drive a small car down its stairways. Ulysses S. Grant stayed here on his world tour in the 1870s. Charlie Chaplin and George Bernard Shaw and Albert Einstein stayed here too, when Shanghai was the place to visit in Asia in the early part of the twentieth century. Urban myth has it that, in the nineteenth century, you could order opium from room service at the Astor House, and that Zhou Enlai, who would go on to be China’s premier, hid in the Astor House when he was a Communist agitator in the 1920s. Shanghai, more than most cities, is suffused with urban myths.

Staying here is also personally nostalgic for me. It was the first hotel I ever stayed at in Shanghai, in the summer of 1988. After my year’s language study, I was joined by a beautiful classmate from my university in England. We were going to travel around China for three months by train before taking the Trans-Siberian Railroad back through the Soviet Union to Europe.

We stayed in the dollar-a-bed dorms for backpackers at the Astor House (which still exist) that baking hot summer. We wandered the streets, getting a feel for the new Shanghai as the city slowly crept out of its Maoist cocoon. We sat up late into the night, out on the hotel’s old wood-paneled balcony, trying to work out China, the universe, and, of course, ourselves. That beautiful classmate is now my wife and has just spent the last six years with me in China. As I lift my backpack up to my room alone, I can’t help smiling at her in the faded mirror of the rickety old elevator.

Before going for dinner, I pull on my shorts and running shoes and head out for a jog. If this is a time of change for China, it is also, I hope, a time of change for me, and more specifically for my waistline. I’m trying to get rid of the ten (okay, nearer fifteen) extra pounds that six years of Chinese food have deposited about my person. This need has become more urgent because of what has been happening—or not—on the top of my head. After a relatively hirsute youth, the spiteful Hair Gods—curse them—have begun to pull the rug from under (and over) me. So, resolving not to reach forty both fat and bald, I’ve rashly signed up to run the Beijing Marathon, all 26.2 miles of it, in the fall. I’d begun training a few miles a day before setting off from Beijing and am hoping to increase the daily distance as I travel throughout the summer, then run the marathon before finally leaving for London.

I set out with great intentions, despite the heat, but make the mistake of running along the pedestrian walkway between the Bund and the river. The area is so crowded that the jog quickly becomes a game of human pinball. One of the occupational hazards of living in China is that there is not much elbow room anywhere (until you reach the Gobi Desert). I attempt a sweaty slalom through the crowd for about two-tenths of a mile, then decide to leave the remaining twenty-six for the morning and stagger ingloriously back to the hotel for a shower.

My first evening in Shanghai is spent on the terrace of a restaurant called New Heights. It sits atop Three on the Bund, one of the row of venerable colonial buildings that have recently been renovated, a few hundred yards along the waterfront from my hotel. Three on the Bund contains the new flagship Giorgio Armani store, an art gallery, an Evian spa, and four swanky restaurants, including New Heights, at the very top, with its open-air terrace suspended seven stories above the road. From the terrace you have one of the most intoxicating restaurant views in the world, looking down on the ten-lane highway of the Bund and across the Huangpu River at the extraordinary, newly built district of Pudong.

The word Bund comes from an old Hindi word meaning an embankment and was brought by the British from India. The area around the Bund was where the first warehouses (called “go-downs”) were built by the opium traders who flocked to China in the mid– nineteenth century to make their fortunes.

The sun that the opium traders watched setting over the Huangpu is setting for me as I arrive on the terrace with my beer. A gentle, warm breeze floats in off the river, wafting in the same scent of opportunity that it did more than 150 years ago. The go-downs and the junks, the clipper ships and the opium dens have given way to the shiny glass and metal of a twenty-first-century city. Fluttering from several of the neighboring colonial buildings is the red flag of the Chinese Communist Party, drowned out by the buzzing, capitalist scene below. The clock tower of the old waterfront Customs House, built in 1925 and modeled on Big Ben in London, strikes the hour with Chairman Mao’s favorite tune, “The East Is Red.” But the East is no longer red. The plumage of capitalism is multicolored, and the view along the Bund is a blaze of green, blue, and white light, screaming out an elegy to Marxist economics. News reports say that China is suffering a severe shortage of electricity, but you wouldn’t know it from the wattage that sizzles into the hot summer night sky here.

Threading its way through the midst of all this is the river itself, the dark, slow-moving Huangpu, dribbling down the chin of the Yangtze Delta from the mouth of the mother river itself. Three massive barges, laden with coal, are pushing upstream, so low in the water that they almost look like submarines. A larger cargo ship blasts out its horn, as if to remind the postmodern diners high above the Bund that the Industrial Revolution is still taking place down below.

Seated among the many foreign businessmen, the wealthy Chinese diners at New Heights are the new elite, who have gained a taste for miso-glazed tuna, zabaglione, and Pinot Noir. People talking about mergers and acquisitions, killer applications, and streaming TV on their cell phones. People who show how far China has come in thirty years of economic reform. Trendy, wealthy, modern Chinese people, greeting one another over cocktails, joking and laughing with all the confidence of a room full of wealthy New York diners. From the kowtow to the air kiss in less than a century.

Ask any of these people about China’s future, and there would be no question. Their natural Chinese modesty might prevent boasting or gloating about China’s potential greatness, but for the nouveaux riches of Shanghai, the future is bright.

New York City makes a good comparison. Beijing is Washington, D.C., a capital city, too obsessed with politics to be at the forefront of commerce. Shanghai is Manhattan, although in many ways it is Manhattan in about 1910—a boomtown with immigrants flooding in. There are roughly 13 million people in Shanghai (New York in 1910 had about 5 million). As in New York a hundred years ago, many of these people have just arrived from somewhere else.

There is no Statue of Liberty to welcome them here, but as I stand looking out across the corrugated river to the Elysian fields of Pudong, it seems to me there should be. Or at least a Statue of Opportunity. Since the city started growing as a foreign trading post, in the 1840s, Shanghai has always been the Mother of Exiles. The difference from New York is that here the exiles are internal, not coming from an old world to build a new but trying to turn the old world into a new one, and that is a much harder task. They are refugees not from ancient lands across the ocean, from Dublin or Kiev or Palermo, but from inland. They are huddled masses from Hefei and Xinyang and Lanzhou, the cities I will be visiting on my journey along Route 312.

One shiny new office tower on the other side of the river has become a huge TV screen, with advertisements and government propaganda alternately lighting up the entire side of the building, one message replaced five seconds later by another.

Welcome to Shanghai. Tomorrow will be even more beautiful.

1,746 more days until the Shanghai World Expo.

Sexual equality is a basic policy of our country.

Eat Dove chocolate.

After dinner, I wander slowly back down the Bund, avoiding the legion of beggars loitering at the door of the restaurant, heading across the road to the walkway on the waterfront where I had tried to jog earlier in the evening. You can keep Fifth Avenue, and Piccadilly, and the Champs-Élysées. This is my favorite urban walk in all the world. There is nothing quite like it, especially on a hot summer evening. The energy, the atmosphere, the hope, the possibilities, the past, the future, it is all here. Downtown Shanghai makes you feel that finally, after centuries of trying, China may be on the edge of greatness once again.

Thousands of tourists, Chinese and Western, are milling along the pedestrian walkway, their flashbulbs popping like fireflies in the half-light. The Westerners are doing what Westerners always do in Shanghai, trying to re-create the past as they snap photos of the old colonial buildings. The Chinese are also doing what Chinese people always do, trying to escape the past as they snap their photos in the opposite direction, gazing out across the river toward the dazzling ziggurats of Pudong.

Shanghai had been slow to emerge from its socialist slumber in the 1980s. It did not really take off until a group of the city’s politicians took over at the top of the Communist Party after the crushing of the pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in June 1989. Then, in the 1990s, Shanghai’s economy soared, as the hope and idealism of the 1980s were consumed upon the bonfire of nihilism and cash.

Pudong was just old docks and paddy fields until the early 1990s. Now it has come to embody the modern Chinese zeitgeist, two hundred square miles of offices, apartments, and shopping malls to add to the superlatives of a city that already boasts the world’s fastest train, the world’s highest hotel, and some of the world’s tallest buildings. When you look out at Pudong, it’s easy to believe that the nine most powerful men in China (who make up the Standing Committee of the Communist Party Politburo) are all engineers.

I walk the length of the Bund, then cross back under the road, past the buskers and the beggars in the underpass, toward the entrance of the grande dame of the Bund, the Peace Hotel. Formerly known as the Cathay, it was built in 1929 by the scion of one of prewar Shanghai’s famous families of Iraqi Jews, the real estate magnate Victor Sassoon. The center of social gravity shifted in the 1930s from the Astor House around the corner to the Cathay. Its jazz was even more jumping, its rooms even more Art Deco a-go-go. Noël Coward, struck down by flu during a stay in 1930, wrote Private Lives in one of the suites at the Cathay.

“Roleksu, Roleksu.”

A voice emerges from the shadows, uttering the normal greeting of the hucksters who loiter outside the Peace Hotel as they flash fake watches from their pockets for your perusal. China is, of course, the world center for fake goods. Gucci bags, Rolex watches, Ralph Lauren shirts are all yours for a few bucks. If it’s clear you don’t want any of these, the pitch suddenly changes direction.

“Ladies bar, ladies bar,” whispers the man in a broken English without apostrophes. “You want go ladies bar?”

Communist orthodoxy, and with it Communist morality, have been lifted, and anything goes now. Usually, a few choice words in Chinese persuade the hucksters that you’ve been here before and you really don’t want any of their fake goods or seedy nightclubs. But tonight, as this particularly persistent guy goes through the list of what he has, and I respond with a crisp bu yao (not want!) to each one, he eventually comes up with one I haven’t heard before.

“Gol-fu,” he says. “Gol-fu.”

I stop to look him squarely in the face and can smell the garlic on his breath. “What?”

The magnetic levitation train that links Shanghai’s gleaming new Pudong Airport with the center of the city glides out of the airport station and within about two minutes has reached 270 miles per hour. Billboards flash past, almost unreadable. Suspended magnetically along a track that runs some fifty feet above the ground, the train scythes toward the center of China’s most modern city. The landscape is surprisingly American—sprawling, low-rise, newly built. The gray bullet leans lazily to the left as it shoots over one of Pudong’s main freeways, past cavernous supermarkets and rows of polished new pink and white apartment blocks.

The maglev, as it is known, cost $1.2 billion to build and is the first commercially run train of its kind in the world.

Six weeks before reaching Starry Gorge and the Gobi Desert, I had arrived by plane in Shanghai from Beijing to start my three-thousand-mile road trip along Route 312. I’d been too busy to make many preparations and had only a faint idea of whom I might talk to when I got here.

Almost before the maglev’s twenty-mile journey has begun, it has ended. The train eases into the terminus, not far from the new jungle of high-rise buildings that make up downtown Shanghai. I look at my watch as I heave my backpack out onto the platform. “Bu cuo. Not bad.” I nod to the smartly dressed female ticket collector standing beside the door. “Eight minutes.”

“Seven minutes, twenty seconds,” she replies without smiling.

The streets outside the terminus are a cacophony of noise and motion. There is an intangible feel in Shanghai, an urgency, a hope and optimism that hangs in the air all around you from the minute you arrive. People are pushing forward, with their feet and in their heads, building a future, building a country, moving toward some distant, unseen goal.

I’ve chosen to stay at the slightly down-at-heel but gloriously historic Astor House Hotel, the first foreign hotel to be established in Shanghai, in 1846. The hotel sits at one end of the Bund, the city’s original main thoroughfare, which runs along the Huangpu River. The Bund has for more than 150 years been the interface between Shanghai and the arriving yang ren, or Ocean People, as foreigners have always been known.

The Astor House Hotel has witnessed the whole sweep of China’s emergence into the modern world, from English opium running in the 1840s through the tea dances of polite society in the 1920s to the excesses of Maoist China in the 1960s. The Art Deco ceilings are high, the creaky floorboards are original, and you could drive a small car down its stairways. Ulysses S. Grant stayed here on his world tour in the 1870s. Charlie Chaplin and George Bernard Shaw and Albert Einstein stayed here too, when Shanghai was the place to visit in Asia in the early part of the twentieth century. Urban myth has it that, in the nineteenth century, you could order opium from room service at the Astor House, and that Zhou Enlai, who would go on to be China’s premier, hid in the Astor House when he was a Communist agitator in the 1920s. Shanghai, more than most cities, is suffused with urban myths.

Staying here is also personally nostalgic for me. It was the first hotel I ever stayed at in Shanghai, in the summer of 1988. After my year’s language study, I was joined by a beautiful classmate from my university in England. We were going to travel around China for three months by train before taking the Trans-Siberian Railroad back through the Soviet Union to Europe.

We stayed in the dollar-a-bed dorms for backpackers at the Astor House (which still exist) that baking hot summer. We wandered the streets, getting a feel for the new Shanghai as the city slowly crept out of its Maoist cocoon. We sat up late into the night, out on the hotel’s old wood-paneled balcony, trying to work out China, the universe, and, of course, ourselves. That beautiful classmate is now my wife and has just spent the last six years with me in China. As I lift my backpack up to my room alone, I can’t help smiling at her in the faded mirror of the rickety old elevator.

Before going for dinner, I pull on my shorts and running shoes and head out for a jog. If this is a time of change for China, it is also, I hope, a time of change for me, and more specifically for my waistline. I’m trying to get rid of the ten (okay, nearer fifteen) extra pounds that six years of Chinese food have deposited about my person. This need has become more urgent because of what has been happening—or not—on the top of my head. After a relatively hirsute youth, the spiteful Hair Gods—curse them—have begun to pull the rug from under (and over) me. So, resolving not to reach forty both fat and bald, I’ve rashly signed up to run the Beijing Marathon, all 26.2 miles of it, in the fall. I’d begun training a few miles a day before setting off from Beijing and am hoping to increase the daily distance as I travel throughout the summer, then run the marathon before finally leaving for London.

I set out with great intentions, despite the heat, but make the mistake of running along the pedestrian walkway between the Bund and the river. The area is so crowded that the jog quickly becomes a game of human pinball. One of the occupational hazards of living in China is that there is not much elbow room anywhere (until you reach the Gobi Desert). I attempt a sweaty slalom through the crowd for about two-tenths of a mile, then decide to leave the remaining twenty-six for the morning and stagger ingloriously back to the hotel for a shower.

My first evening in Shanghai is spent on the terrace of a restaurant called New Heights. It sits atop Three on the Bund, one of the row of venerable colonial buildings that have recently been renovated, a few hundred yards along the waterfront from my hotel. Three on the Bund contains the new flagship Giorgio Armani store, an art gallery, an Evian spa, and four swanky restaurants, including New Heights, at the very top, with its open-air terrace suspended seven stories above the road. From the terrace you have one of the most intoxicating restaurant views in the world, looking down on the ten-lane highway of the Bund and across the Huangpu River at the extraordinary, newly built district of Pudong.

The word Bund comes from an old Hindi word meaning an embankment and was brought by the British from India. The area around the Bund was where the first warehouses (called “go-downs”) were built by the opium traders who flocked to China in the mid– nineteenth century to make their fortunes.

The sun that the opium traders watched setting over the Huangpu is setting for me as I arrive on the terrace with my beer. A gentle, warm breeze floats in off the river, wafting in the same scent of opportunity that it did more than 150 years ago. The go-downs and the junks, the clipper ships and the opium dens have given way to the shiny glass and metal of a twenty-first-century city. Fluttering from several of the neighboring colonial buildings is the red flag of the Chinese Communist Party, drowned out by the buzzing, capitalist scene below. The clock tower of the old waterfront Customs House, built in 1925 and modeled on Big Ben in London, strikes the hour with Chairman Mao’s favorite tune, “The East Is Red.” But the East is no longer red. The plumage of capitalism is multicolored, and the view along the Bund is a blaze of green, blue, and white light, screaming out an elegy to Marxist economics. News reports say that China is suffering a severe shortage of electricity, but you wouldn’t know it from the wattage that sizzles into the hot summer night sky here.

Threading its way through the midst of all this is the river itself, the dark, slow-moving Huangpu, dribbling down the chin of the Yangtze Delta from the mouth of the mother river itself. Three massive barges, laden with coal, are pushing upstream, so low in the water that they almost look like submarines. A larger cargo ship blasts out its horn, as if to remind the postmodern diners high above the Bund that the Industrial Revolution is still taking place down below.

Seated among the many foreign businessmen, the wealthy Chinese diners at New Heights are the new elite, who have gained a taste for miso-glazed tuna, zabaglione, and Pinot Noir. People talking about mergers and acquisitions, killer applications, and streaming TV on their cell phones. People who show how far China has come in thirty years of economic reform. Trendy, wealthy, modern Chinese people, greeting one another over cocktails, joking and laughing with all the confidence of a room full of wealthy New York diners. From the kowtow to the air kiss in less than a century.

Ask any of these people about China’s future, and there would be no question. Their natural Chinese modesty might prevent boasting or gloating about China’s potential greatness, but for the nouveaux riches of Shanghai, the future is bright.

New York City makes a good comparison. Beijing is Washington, D.C., a capital city, too obsessed with politics to be at the forefront of commerce. Shanghai is Manhattan, although in many ways it is Manhattan in about 1910—a boomtown with immigrants flooding in. There are roughly 13 million people in Shanghai (New York in 1910 had about 5 million). As in New York a hundred years ago, many of these people have just arrived from somewhere else.

There is no Statue of Liberty to welcome them here, but as I stand looking out across the corrugated river to the Elysian fields of Pudong, it seems to me there should be. Or at least a Statue of Opportunity. Since the city started growing as a foreign trading post, in the 1840s, Shanghai has always been the Mother of Exiles. The difference from New York is that here the exiles are internal, not coming from an old world to build a new but trying to turn the old world into a new one, and that is a much harder task. They are refugees not from ancient lands across the ocean, from Dublin or Kiev or Palermo, but from inland. They are huddled masses from Hefei and Xinyang and Lanzhou, the cities I will be visiting on my journey along Route 312.

One shiny new office tower on the other side of the river has become a huge TV screen, with advertisements and government propaganda alternately lighting up the entire side of the building, one message replaced five seconds later by another.

Welcome to Shanghai. Tomorrow will be even more beautiful.

1,746 more days until the Shanghai World Expo.

Sexual equality is a basic policy of our country.

Eat Dove chocolate.

After dinner, I wander slowly back down the Bund, avoiding the legion of beggars loitering at the door of the restaurant, heading across the road to the walkway on the waterfront where I had tried to jog earlier in the evening. You can keep Fifth Avenue, and Piccadilly, and the Champs-Élysées. This is my favorite urban walk in all the world. There is nothing quite like it, especially on a hot summer evening. The energy, the atmosphere, the hope, the possibilities, the past, the future, it is all here. Downtown Shanghai makes you feel that finally, after centuries of trying, China may be on the edge of greatness once again.

Thousands of tourists, Chinese and Western, are milling along the pedestrian walkway, their flashbulbs popping like fireflies in the half-light. The Westerners are doing what Westerners always do in Shanghai, trying to re-create the past as they snap photos of the old colonial buildings. The Chinese are also doing what Chinese people always do, trying to escape the past as they snap their photos in the opposite direction, gazing out across the river toward the dazzling ziggurats of Pudong.

Shanghai had been slow to emerge from its socialist slumber in the 1980s. It did not really take off until a group of the city’s politicians took over at the top of the Communist Party after the crushing of the pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in June 1989. Then, in the 1990s, Shanghai’s economy soared, as the hope and idealism of the 1980s were consumed upon the bonfire of nihilism and cash.

Pudong was just old docks and paddy fields until the early 1990s. Now it has come to embody the modern Chinese zeitgeist, two hundred square miles of offices, apartments, and shopping malls to add to the superlatives of a city that already boasts the world’s fastest train, the world’s highest hotel, and some of the world’s tallest buildings. When you look out at Pudong, it’s easy to believe that the nine most powerful men in China (who make up the Standing Committee of the Communist Party Politburo) are all engineers.

I walk the length of the Bund, then cross back under the road, past the buskers and the beggars in the underpass, toward the entrance of the grande dame of the Bund, the Peace Hotel. Formerly known as the Cathay, it was built in 1929 by the scion of one of prewar Shanghai’s famous families of Iraqi Jews, the real estate magnate Victor Sassoon. The center of social gravity shifted in the 1930s from the Astor House around the corner to the Cathay. Its jazz was even more jumping, its rooms even more Art Deco a-go-go. Noël Coward, struck down by flu during a stay in 1930, wrote Private Lives in one of the suites at the Cathay.

“Roleksu, Roleksu.”

A voice emerges from the shadows, uttering the normal greeting of the hucksters who loiter outside the Peace Hotel as they flash fake watches from their pockets for your perusal. China is, of course, the world center for fake goods. Gucci bags, Rolex watches, Ralph Lauren shirts are all yours for a few bucks. If it’s clear you don’t want any of these, the pitch suddenly changes direction.

“Ladies bar, ladies bar,” whispers the man in a broken English without apostrophes. “You want go ladies bar?”

Communist orthodoxy, and with it Communist morality, have been lifted, and anything goes now. Usually, a few choice words in Chinese persuade the hucksters that you’ve been here before and you really don’t want any of their fake goods or seedy nightclubs. But tonight, as this particularly persistent guy goes through the list of what he has, and I respond with a crisp bu yao (not want!) to each one, he eventually comes up with one I haven’t heard before.

“Gol-fu,” he says. “Gol-fu.”

I stop to look him squarely in the face and can smell the garlic on his breath. “What?”

Recenzii

Advance praise for China Road

“How I envy Rob Gifford and his journey along China Road. How grateful I am to him for allowing me to share the trip through his vivid writing and his deep knowledge of and great love for China. As vicarious enjoyment goes, this one’s a ten.”

–Ted Koppel, managing editor, Discovery Channel

“Rob Gifford has found the perfect road trip. His years in China have given him a keen eye and a deep understanding of the country’s contradictions; he’s the perfect guide to this magnificent road from Shanghai to the Kazakhstan border.”

–Peter Hassler, author of River Town and Oracle Bones

“My gosh, I loved Rob Gifford’s book. His journey along Route 312 is a great road story–from Hooters in Shanghai to the Iron House of Confucianism. China Road is insightful, funny, analytical, anecdotal, full of humble humor and magnificent discoveries.”

–Scott Simon, host of NPR’s Weekend Edition and author of Pretty Birds

“Here is China end to end, told from its equivalent of Route 66 as Gifford journeys from Shanghai to the distant west, talking to truck drivers, merchants, hermits, and whores. Gifford portrays China with affection and humor, in all its complexity, energy, hopefulness, and risk.”

–Andrew J. Nathan, Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science, Columbia University

“Equal parts Bill Bryson and Jonathan Spence. Gifford is great company and great fun, and China Road is a terrific, highly readable book.”

–Jim Yardley, Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times Beijing correspondent

“A great book, a terrific read. Rob Gifford’s story is as engaging as any travel writing, but it is equally full of historical and philosophical wisdom about the future of the world’s largest country.”

–Joseph S. Nye, Jr., former assistant secretary of defense, Distinguished Service Professor, Harvard University

“After six years in Beijing, NPR’s Rob Gifford has written a wonderfully reflective but also well-informed account of his road trip across China. His knowledge and insight about China’s past and present do a marvelous job in helping the reader understand all the challenges that confront this very dynamic country’s future.”

–Orville Schell, director, the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations

From the Hardcover edition.

“How I envy Rob Gifford and his journey along China Road. How grateful I am to him for allowing me to share the trip through his vivid writing and his deep knowledge of and great love for China. As vicarious enjoyment goes, this one’s a ten.”

–Ted Koppel, managing editor, Discovery Channel

“Rob Gifford has found the perfect road trip. His years in China have given him a keen eye and a deep understanding of the country’s contradictions; he’s the perfect guide to this magnificent road from Shanghai to the Kazakhstan border.”

–Peter Hassler, author of River Town and Oracle Bones

“My gosh, I loved Rob Gifford’s book. His journey along Route 312 is a great road story–from Hooters in Shanghai to the Iron House of Confucianism. China Road is insightful, funny, analytical, anecdotal, full of humble humor and magnificent discoveries.”

–Scott Simon, host of NPR’s Weekend Edition and author of Pretty Birds

“Here is China end to end, told from its equivalent of Route 66 as Gifford journeys from Shanghai to the distant west, talking to truck drivers, merchants, hermits, and whores. Gifford portrays China with affection and humor, in all its complexity, energy, hopefulness, and risk.”

–Andrew J. Nathan, Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science, Columbia University

“Equal parts Bill Bryson and Jonathan Spence. Gifford is great company and great fun, and China Road is a terrific, highly readable book.”

–Jim Yardley, Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times Beijing correspondent

“A great book, a terrific read. Rob Gifford’s story is as engaging as any travel writing, but it is equally full of historical and philosophical wisdom about the future of the world’s largest country.”

–Joseph S. Nye, Jr., former assistant secretary of defense, Distinguished Service Professor, Harvard University

“After six years in Beijing, NPR’s Rob Gifford has written a wonderfully reflective but also well-informed account of his road trip across China. His knowledge and insight about China’s past and present do a marvelous job in helping the reader understand all the challenges that confront this very dynamic country’s future.”

–Orville Schell, director, the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

An acclaimed National Public Radio reporter takes a dramatic journey along China's Route 312 from its start in the boomtown of Shanghai to its end on the border with Kazakhstan. Along the way, he poses crucial questions regarding China's future as a super power.

Caracteristici

Rob Gifford's eight-part radio series about travelling along Route 312 was broadcast to acclaim to NPR's 22 million listeners.