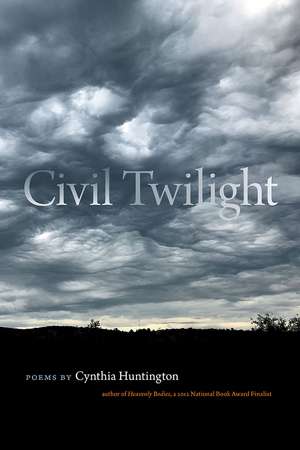

Civil Twilight: Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

Autor Cynthia Huntingtonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2024

Civil twilight is the astronomical term for the minutes just before sunrise and just after sunset. If one took a snapshot, it would be impossible to tell whether the light was increasing or diminishing. The poems in Civil Twilight arise in this liminal space. With luminous precision, Cynthia Huntington examines the civil twilight we live in now, unsure of whether the darkness is closing in or whether the light is about to break.

Here the poet is both skeptic and seeker, for any hope worth discovering needs to withstand the facts at hand. Is everything getting worse, or are things about to improve? Or is this the way things have always been, both hopeful and terrifying, and it is our questions that need to change? In part one, the speaker strives for balance by maintaining light and warmth in a cold season. In part two, American scenes of construction and destruction are set beside moments from history: Rome, the British Empire, and American immigration. Part three enfolds questions of history and power within winter scenes and the artist’s imagination. In part four, the speaker looks back and admits answers remain elusive, yet points to the new ways of thinking and feeling about survival that have resulted from the work. And here, the half-light shifts. In a world teetering on the edge of collapse, Civil Twilight wrestles hard-won hope from disquiet, coming to rest in what is.

Din seria Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

-

Preț: 153.88 lei

Preț: 153.88 lei -

Preț: 162.16 lei

Preț: 162.16 lei -

Preț: 87.22 lei

Preț: 87.22 lei -

Preț: 96.08 lei

Preț: 96.08 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 27%

Preț: 119.35 lei

Preț: 119.35 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.35 lei

Preț: 119.35 lei - 18%

Preț: 112.55 lei

Preț: 112.55 lei - 27%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 27%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei -

Preț: 90.14 lei

Preț: 90.14 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 88.45 lei

Preț: 88.45 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 27%

Preț: 118.47 lei

Preț: 118.47 lei -

Preț: 83.30 lei

Preț: 83.30 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.76 lei

Preț: 118.76 lei - 22%

Preț: 119.64 lei

Preț: 119.64 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei -

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei -

Preț: 83.06 lei

Preț: 83.06 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.66 lei

Preț: 118.66 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 18%

Preț: 112.48 lei

Preț: 112.48 lei -

Preț: 78.73 lei

Preț: 78.73 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 179.08 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 269

Preț estimativ în valută:

34.27€ • 36.03$ • 28.31£

34.27€ • 36.03$ • 28.31£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Livrare express 12-18 martie pentru 15.21 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809339303

ISBN-10: 0809339307

Pagini: 84

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 6 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

ISBN-10: 0809339307

Pagini: 84

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 6 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

Notă biografică

Cynthia Huntington is the author of several collections of poetry, including Terra Nova; Heavenly Bodies, which was nominated for a National Book Award; Levis Prize-winner The Radiant; We Have Gone to the Beach, which won the Beatrice Hawley Award and the Jane Kenyon Award; and The Fish-Wife; and the nonfiction prose volume The Salt House. Huntington is an emeritus professor of English and creative writing at Dartmouth College, a former Guggenheim Fellow, a former poet laureate of New Hampshire, and a two-time National Endowment for the Arts Fellow in Poetry.

Extras

Hard Frost

How do you like this morning, frozen dandelion?

Shriveled and black-fringed, yet you seem more distinct—

dilly-toothed rosette, green-darkening wraith.

My old cat glowers on the doorstep, shrinks back.

He’s saying it’s time for fires.

And what of that blue jay, whose loud complaint

startles the dreaming maple to throw up her arms,

flustering leaves down in accolade, rave

to his magnitude? What he wants wants wants

is to live of course, and yes he loves the world

as well. He is a blue prince among the colors of fire.

Bright as a break in clouds, he struts and glares.

Hello. Come closer please. One dazzled fly

creaking to life among the blackened stalks.

Dream Certification

It was like a Russian novel: everyone coming and going in the big room overlooking the lake,

drifting into the kitchen for tea, then back to their rooms, or wrapping themselves in coats and

scarves to hike out on the woods’ trails, or up the road by the lake, then banging back inside,

chattering, strewing boots and gloves and hats and snowy jackets in the cold entry hall.

Forbidden to walk out on the lake: thin ice with wet patches rising through. “But the men are out

there fishing.” “Yes, they know where to walk.”

I lay on the sofa with my book. On the other side of a screen Ina was helping Louise decipher a

bus schedule, speaking English, which is not either of their first languages, but Ina doesn’t speak

French, and no one speaks Finnish (except everyone who lives here—but we don’t live here, we

are guests.)

Cissy is playing some kind of gypsy music on a guitar she found leaned up in the closet and

Brandon and Dani are working on a sculpture with string and tags from teabags tacked to the

wall, a model to sketch out an idea, and if they use wire instead of string for the next version,

Nate says he can make it play music. Beautiful Clara is brooding on a floor cushion, sitting

cross-legged with a drawing pad in her lap, staring out the window, adrift in a sadness known

only to the beautiful young—that time when you first feel how vast your loneliness is, but still

believe it can be healed.

Omar has taken the car into town, along with our liquor orders. Someone is heating a curry in the

kitchen. It smells—out of place—in this cold light, but good. I’m thinking I didn’t come here for

company, I have work to do, but my room is cold, even with a blanket over my lap, and I like it

here in the commons after all, falling into my book and surfacing again.

Now I remember I didn’t go out that day because I had burned my foot—an accident involving a

pan of hot chicken broth that spilled and splashed up and clung to my skin, burned deep through

layers, and I was lying on the sofa with my leg propped on pillows, and the foot throbbed and

was too swollen for a shoe. That week of wool socks over bandages, and a size 13 slipper, also

found in the closet, and I was waiting with some small urgency for Omar to return and bring my

Irish whiskey. And it wasn’t a Russian novel at all, though one does require an invalid, and a

house party, but no one was arguing or about to lose their estate, so no...

Finally I pulled a blanket up over my shoulders and dozed. It was that kind of day. Cozy, like

sleeping in the back of the car, driving home on a winter night, my parents talking in the front

seat about nothing interesting, and tucking my head down in my coat—the cold outside and the

musty heater and the car’s rolling motion along the two-lane road, carried safe. When I woke up

Dani was showing slides projected on the wall. It was dark, though still afternoon, and Omar had

returned and everyone was drinking and talking softly and my bottle sat on the table beside my

hand.

Can I call it a dream if it was real? Maybe a small fever attended the burn, a drowsy waking

in which I found myself remembering the day even as it was happening, so that I seemed to be

in two lives at once, a kind of wholeness. no less true for being imagined. Not every dream

is an illusion. And imagination is a place: I remember being there.

The Meek Shall Eat Our Dust

The first people came in Chevrolets. Some had canoes strapped to their roof racks, with paddles

set crosswise, for that they were holy. Their children had sticky hands, and the middle girl, who

was carsick, vomited frequently. The brothers quarreled and swatted each other, like brothers in

the Bible their mother said. The parents smoked in the front seat and tipped their ashes out the

windows. Behind them, forest fires raged. Just past the mountains the car broke down, for it was

weary and could go no more. There by the road they waited. An angel came and bid them to

keep faith and know that they were not forgotten. This heartened them and they hoped that a tow

truck had been called, as they were hot and weary, and without recourse for the car was still

broke down. As they sat there by the roadside, faithful in sorrow, a Chrysler sailed past. A

powder blue convertible with clean whitewalls and silvery chrome, radio thumping a-wimeweh

a-wimeweh from state-of-the-art speakers. Froth of music, and chiffon scarves ruffling in the

breeze. Look quick: those are our ancestors, lost in clouds of road dust gasoline alley glory. As

for that family stranded by the roadside, who loved each other and were patient in suffering, they

have not been heard of since.

Garden Bench

Late August flickers,

the sultry and the gleam.

Brief mountain summer.

The garden bench pale under porch lights,

a silk current shines through

its iron scrolls, and feels its way

among the branches and leaves.

The garden sleeps

and night swims in, filling every form.

Larvae spun into chrysalides.

The bark beetle chewing.

Night is a place. We enter it.

Large, with no edges, it has curved on itself,

an inside with no outside. I can put my hand

through it without tearing. It moves

through me too, though it is everywhere.

Some bread and cheese,

a glass of water. Are you lonely here?

It’s so much more than that. The great mass

of the maple tree, standing in the yard,

fifty years growing, half of it underground.

Each branch a root. Crown in the sky.

Close your eyes, let it raise you.

If I were that.

Or a stone

broken from the ledge, lying among leaves.

What do you call a broken stone? A stone.

Always complete.

A door, moved by a handle back and forth,

one arc governed by a hinge,

the plane of the door shuttering light,

opening and closing space.

How times comes and goes in things.

An old pot holding water.

Or a moth the porch light baffled.

A work glove left in the grass. Or a nail,

driven to its limit, tight inside the wood.

Holding it, held.

[end of excerpt]

How do you like this morning, frozen dandelion?

Shriveled and black-fringed, yet you seem more distinct—

dilly-toothed rosette, green-darkening wraith.

My old cat glowers on the doorstep, shrinks back.

He’s saying it’s time for fires.

And what of that blue jay, whose loud complaint

startles the dreaming maple to throw up her arms,

flustering leaves down in accolade, rave

to his magnitude? What he wants wants wants

is to live of course, and yes he loves the world

as well. He is a blue prince among the colors of fire.

Bright as a break in clouds, he struts and glares.

Hello. Come closer please. One dazzled fly

creaking to life among the blackened stalks.

Dream Certification

It was like a Russian novel: everyone coming and going in the big room overlooking the lake,

drifting into the kitchen for tea, then back to their rooms, or wrapping themselves in coats and

scarves to hike out on the woods’ trails, or up the road by the lake, then banging back inside,

chattering, strewing boots and gloves and hats and snowy jackets in the cold entry hall.

Forbidden to walk out on the lake: thin ice with wet patches rising through. “But the men are out

there fishing.” “Yes, they know where to walk.”

I lay on the sofa with my book. On the other side of a screen Ina was helping Louise decipher a

bus schedule, speaking English, which is not either of their first languages, but Ina doesn’t speak

French, and no one speaks Finnish (except everyone who lives here—but we don’t live here, we

are guests.)

Cissy is playing some kind of gypsy music on a guitar she found leaned up in the closet and

Brandon and Dani are working on a sculpture with string and tags from teabags tacked to the

wall, a model to sketch out an idea, and if they use wire instead of string for the next version,

Nate says he can make it play music. Beautiful Clara is brooding on a floor cushion, sitting

cross-legged with a drawing pad in her lap, staring out the window, adrift in a sadness known

only to the beautiful young—that time when you first feel how vast your loneliness is, but still

believe it can be healed.

Omar has taken the car into town, along with our liquor orders. Someone is heating a curry in the

kitchen. It smells—out of place—in this cold light, but good. I’m thinking I didn’t come here for

company, I have work to do, but my room is cold, even with a blanket over my lap, and I like it

here in the commons after all, falling into my book and surfacing again.

Now I remember I didn’t go out that day because I had burned my foot—an accident involving a

pan of hot chicken broth that spilled and splashed up and clung to my skin, burned deep through

layers, and I was lying on the sofa with my leg propped on pillows, and the foot throbbed and

was too swollen for a shoe. That week of wool socks over bandages, and a size 13 slipper, also

found in the closet, and I was waiting with some small urgency for Omar to return and bring my

Irish whiskey. And it wasn’t a Russian novel at all, though one does require an invalid, and a

house party, but no one was arguing or about to lose their estate, so no...

Finally I pulled a blanket up over my shoulders and dozed. It was that kind of day. Cozy, like

sleeping in the back of the car, driving home on a winter night, my parents talking in the front

seat about nothing interesting, and tucking my head down in my coat—the cold outside and the

musty heater and the car’s rolling motion along the two-lane road, carried safe. When I woke up

Dani was showing slides projected on the wall. It was dark, though still afternoon, and Omar had

returned and everyone was drinking and talking softly and my bottle sat on the table beside my

hand.

Can I call it a dream if it was real? Maybe a small fever attended the burn, a drowsy waking

in which I found myself remembering the day even as it was happening, so that I seemed to be

in two lives at once, a kind of wholeness. no less true for being imagined. Not every dream

is an illusion. And imagination is a place: I remember being there.

The Meek Shall Eat Our Dust

The first people came in Chevrolets. Some had canoes strapped to their roof racks, with paddles

set crosswise, for that they were holy. Their children had sticky hands, and the middle girl, who

was carsick, vomited frequently. The brothers quarreled and swatted each other, like brothers in

the Bible their mother said. The parents smoked in the front seat and tipped their ashes out the

windows. Behind them, forest fires raged. Just past the mountains the car broke down, for it was

weary and could go no more. There by the road they waited. An angel came and bid them to

keep faith and know that they were not forgotten. This heartened them and they hoped that a tow

truck had been called, as they were hot and weary, and without recourse for the car was still

broke down. As they sat there by the roadside, faithful in sorrow, a Chrysler sailed past. A

powder blue convertible with clean whitewalls and silvery chrome, radio thumping a-wimeweh

a-wimeweh from state-of-the-art speakers. Froth of music, and chiffon scarves ruffling in the

breeze. Look quick: those are our ancestors, lost in clouds of road dust gasoline alley glory. As

for that family stranded by the roadside, who loved each other and were patient in suffering, they

have not been heard of since.

Garden Bench

Late August flickers,

the sultry and the gleam.

Brief mountain summer.

The garden bench pale under porch lights,

a silk current shines through

its iron scrolls, and feels its way

among the branches and leaves.

The garden sleeps

and night swims in, filling every form.

Larvae spun into chrysalides.

The bark beetle chewing.

Night is a place. We enter it.

Large, with no edges, it has curved on itself,

an inside with no outside. I can put my hand

through it without tearing. It moves

through me too, though it is everywhere.

Some bread and cheese,

a glass of water. Are you lonely here?

It’s so much more than that. The great mass

of the maple tree, standing in the yard,

fifty years growing, half of it underground.

Each branch a root. Crown in the sky.

Close your eyes, let it raise you.

If I were that.

Or a stone

broken from the ledge, lying among leaves.

What do you call a broken stone? A stone.

Always complete.

A door, moved by a handle back and forth,

one arc governed by a hinge,

the plane of the door shuttering light,

opening and closing space.

How times comes and goes in things.

An old pot holding water.

Or a moth the porch light baffled.

A work glove left in the grass. Or a nail,

driven to its limit, tight inside the wood.

Holding it, held.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

CONTENTS

Hard Frost

Part One: Snow

After a Line by Transtromer

Now That I Am in Finland and Can Think

Dream Certification

Community Center Yoga

One Lamp in a Doorway and One Down the Valley

At the Death House

Spike

Shelter

Firewood

River Road

Part Two: Civil Twilight

Demolition

The Meek Shall Eat Our Dust

April Pastoral

In Mud Season

Conversion Metric

Dacia

How to Read American History

Late Tenement

Hart Crane

Nijinsky

On a Line from Robinson Jeffers

Home Footage: 1970

Will Spring Ever Come to the North Country

Part Three: Deer in a Gated Park

Deer in a Gated Park: A Poem in Five Parts

Part Four: Garden Bench

View through Apertures

Teshuva

Horse

Private Beach

Jackass Angels

After Pessoa

The Value of Poetry

We Will Be Two

hum

Garden Bench

Hard Frost

Part One: Snow

After a Line by Transtromer

Now That I Am in Finland and Can Think

Dream Certification

Community Center Yoga

One Lamp in a Doorway and One Down the Valley

At the Death House

Spike

Shelter

Firewood

River Road

Part Two: Civil Twilight

Demolition

The Meek Shall Eat Our Dust

April Pastoral

In Mud Season

Conversion Metric

Dacia

How to Read American History

Late Tenement

Hart Crane

Nijinsky

On a Line from Robinson Jeffers

Home Footage: 1970

Will Spring Ever Come to the North Country

Part Three: Deer in a Gated Park

Deer in a Gated Park: A Poem in Five Parts

Part Four: Garden Bench

View through Apertures

Teshuva

Horse

Private Beach

Jackass Angels

After Pessoa

The Value of Poetry

We Will Be Two

hum

Garden Bench

Recenzii

Praise for Heavenly Bodies

“Cynthia Huntington’s Heavenly Bodies is a fearless and exacting exploration of illness, addiction, abuse, and the waning of American idealism. These poems are unblinking in the face of dark subject matter, and surprising in their capacity for hope, for grace. Huntington’s speakers are as vast and compassionate—as empathetic and multitudinous—as Whitman’s, and they sing of the beauty and seductive brutality of survival in a world perpetually ‘alight with new dangers.’”—Judges Citation, National Book Foundation

“Huntington, who can tune a lyric any way she likes, has written exquisite poems, some of which turn tragedy into transcendence...But in this book, we suspect that Huntington is tired of rapture and redemption, and that her real subject is disobedience. Her poems in Heavenly Bodies resist transcendent turns just to please the reader, offering instead the body of the poem as it is, without lipstick or peignoir.”—Julia Shipley, Seven Days

Praise for Terra Nova

“This is a magnificent work, focused on the history of an all but sea-surrounded town. The poet [tells] stories through many voices, from the elevated language of creation myth and prophetic rebuke, to vivid, realistic barroom scenes, hapless and violent, mediated through a voice of personal account and self-accounting. . . . It is one poem with many poems (some of them in prose) carried through the passionate singing rhythm of these voices, becoming the one grand poem that is the book.”—David Ferry, author, Bewilderment, and winner, National Book Award in Poetry

“Provincetown is the locus of this ambitious, wide-ranging, and archetypal collection, which takes up various histories of migration and exile and reimagines them for our time. Terra Nova has the feeling of a biblical prophecy, a lost book that has washed up from the sea.”—Edward Hirsch, author, Gabriel: A Poem

“Cynthia Huntington’s Heavenly Bodies is a fearless and exacting exploration of illness, addiction, abuse, and the waning of American idealism. These poems are unblinking in the face of dark subject matter, and surprising in their capacity for hope, for grace. Huntington’s speakers are as vast and compassionate—as empathetic and multitudinous—as Whitman’s, and they sing of the beauty and seductive brutality of survival in a world perpetually ‘alight with new dangers.’”—Judges Citation, National Book Foundation

“Huntington, who can tune a lyric any way she likes, has written exquisite poems, some of which turn tragedy into transcendence...But in this book, we suspect that Huntington is tired of rapture and redemption, and that her real subject is disobedience. Her poems in Heavenly Bodies resist transcendent turns just to please the reader, offering instead the body of the poem as it is, without lipstick or peignoir.”—Julia Shipley, Seven Days

Praise for Terra Nova

“This is a magnificent work, focused on the history of an all but sea-surrounded town. The poet [tells] stories through many voices, from the elevated language of creation myth and prophetic rebuke, to vivid, realistic barroom scenes, hapless and violent, mediated through a voice of personal account and self-accounting. . . . It is one poem with many poems (some of them in prose) carried through the passionate singing rhythm of these voices, becoming the one grand poem that is the book.”—David Ferry, author, Bewilderment, and winner, National Book Award in Poetry

“Provincetown is the locus of this ambitious, wide-ranging, and archetypal collection, which takes up various histories of migration and exile and reimagines them for our time. Terra Nova has the feeling of a biblical prophecy, a lost book that has washed up from the sea.”—Edward Hirsch, author, Gabriel: A Poem

Descriere

Civil twilight is the astronomical term for the minutes just before sunrise and just after sunset. In this collection, National Book Award finalist Cynthia Huntington examines the civil twilight we live in now, unsure of whether the darkness is closing in or whether the light is about to break.