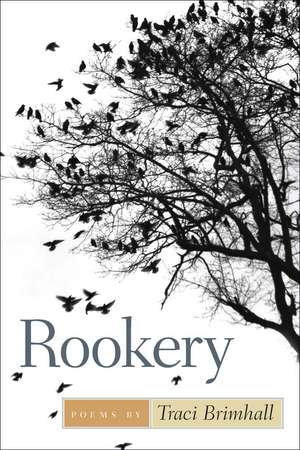

Rookery: Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

Autor Traci Brimhallen Limba Engleză Paperback – 20 oct 2010

Traveling to the most intimate extremes of the human heart

Fraught with madness, brutality, and ecstasy, Traci Brimhall’s Rookery delves into the darkest and most remote corners of the human experience. From the graveyards and battlefields of the Civil War to the ancient forests of Brazil, from desire to despair, landscapes both literal and emotional are traversed in this unforgettable collection of poems. Brimhall guides readers through ever-winding mazes of heartbreak and treachery, and the euphoric dreams of missionaries. The end of days, the intoxication of religion that at times borders on terror, and the post-evangelical experience intertwine with the haunting redemptions and metamorphoses found in violence. These tender yet ruthless poems, brimming with danger and longing, lure readers to “a place where everyone is transformed by suffering.”

Fraught with madness, brutality, and ecstasy, Traci Brimhall’s Rookery delves into the darkest and most remote corners of the human experience. From the graveyards and battlefields of the Civil War to the ancient forests of Brazil, from desire to despair, landscapes both literal and emotional are traversed in this unforgettable collection of poems. Brimhall guides readers through ever-winding mazes of heartbreak and treachery, and the euphoric dreams of missionaries. The end of days, the intoxication of religion that at times borders on terror, and the post-evangelical experience intertwine with the haunting redemptions and metamorphoses found in violence. These tender yet ruthless poems, brimming with danger and longing, lure readers to “a place where everyone is transformed by suffering.”

Din seria Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

-

Preț: 178.97 lei

Preț: 178.97 lei -

Preț: 153.88 lei

Preț: 153.88 lei -

Preț: 161.87 lei

Preț: 161.87 lei -

Preț: 87.22 lei

Preț: 87.22 lei -

Preț: 96.30 lei

Preț: 96.30 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.35 lei

Preț: 119.35 lei - 18%

Preț: 112.55 lei

Preț: 112.55 lei - 27%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 27%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei -

Preț: 90.14 lei

Preț: 90.14 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 88.45 lei

Preț: 88.45 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 27%

Preț: 118.47 lei

Preț: 118.47 lei -

Preț: 83.30 lei

Preț: 83.30 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.76 lei

Preț: 118.76 lei - 22%

Preț: 119.64 lei

Preț: 119.64 lei - 34%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei -

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei -

Preț: 83.06 lei

Preț: 83.06 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.66 lei

Preț: 118.66 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 18%

Preț: 112.48 lei

Preț: 112.48 lei -

Preț: 78.73 lei

Preț: 78.73 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.92 lei

Preț: 118.92 lei - 34%

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 118.58 lei

Preț: 119.35 lei

Preț vechi: 162.59 lei

-27% Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.84€ • 23.90$ • 19.01£

22.84€ • 23.90$ • 19.01£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809329977

ISBN-10: 0809329972

Pagini: 96

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

ISBN-10: 0809329972

Pagini: 96

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Crab Orchard Series in Poetry

Notă biografică

Traci Brimhall, who received her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, recently completed a Jay C. and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellowship at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her poems have appeared in New England Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, FIELD, Southern Review, Indiana Review, and other journals.

Extras

AUBADE WITH A BROKEN NECK

The first night you don't come home

summer rains shake the clematis.

I bury the dead moth I found in our bed,

scratch up a rutabaga and eat it rough

with dirt. The dog finds me and presents

between his gentle teeth a twitching

nightjar. In her panic, she sings

in his mouth. He gives me her pain

like a gift, and I take it. I hear

the cries of her young, greedy with need,

expecting her return, but I don't let her go

until I get into the house. I read

the auspices-the way she flutters against

the wallpaper's moldy roses means

all can be lost. How she skims the ceiling

means a storm approaches. You should see

her in the beginnings of her fear, rushing

at the starless window, her body a dart,

her body the arrow of longing, aimed,

as all desperate things are, to crash

not into the object of desire,

but into the darkness behind it.

REGRET WITH WILDFLOWERS

So much can hide in a field. A prairie dog

can escape the hawk that devils it. A seed

can wait until it is ready to be broken open,

the earth ready to transform it. Today, aphids

ravage the wildflowers, bison graze in the pasture,

and I am returning home from another mistake.

Of all my minor regrets, this is the worst-

I let you assure me that desire is like a boy

who throws rocks at a deer decaying in the river.

That innocent. That brutal. I let you hold me down,

let you draw my blood to the surface of my skin

and call it an accident. But now I see how awful

the sky is. How stark. How bare. How, when clouds

expose the sun, horses tilt their heads with pleasure.

DISCIPLINE WITH LINES FROM FIRST CORINTHIANS

You try and teach me to be careful with my thoughts

or else, when the day comes, my ashes may not ascend

with the rest of the believers, but I can't help myself.

I'm shy and susceptible to voices stirring in the clock

at midnight whispering Listen, I tell you a mystery:

we will not all sleep, but we will all be changed.

You say it is not the animal in us that loves to struggle,

but the spirit that wants to be locked in the crucible

of flesh until the soul burns clean. Mother, I beat my body

and make it my slave. I see a snake swallow its tail and know

we are all infinite. Father, take me to the field where snow

is melting through the ribs of the deer it covered all winter.

There is a word inside every perishable thing aching

to be spoken so it may live again. I've heard it.

I found a bunting drowsing in the bushes, pinned back

its wings and listened to its indigo lullaby, its song

like last century's wind asking How can some of you say

there is no resurrection? How could any of us be damned?

COME BACK TO ME

If you go to the ruins, a man will sell you

the story of a queen for a kiss. This is the commerce

of beauty. His lips. Your imagination. A moment

of closed eyes and forgetting. He will tell you

it is good luck to take your husband and lay him

down on a tomb for a night, but when you say

you're alone, he insists that this is better-

to lay yourself down under a fire that has no heat

and pray to the Tunisian moon for a barren orchard

and an ocean without sharks. There is comfort

in a lie, but there is also a thief who will take you

unarmed in a dark town asking only for a kiss

and the money in your wallet. And you will

give it. Freely. Because a man asked for part of you,

and because you've been alone for so long

you've forgotten what a man tastes like.

Because it's your last night in Africa and twelve

dollars is not too much to lose. Because he says

Come back to me even as you are showing him

your breasts in the cemetery, and because, in truth,

you like the way the moonlight looks on his skin.

The first night you don't come home

summer rains shake the clematis.

I bury the dead moth I found in our bed,

scratch up a rutabaga and eat it rough

with dirt. The dog finds me and presents

between his gentle teeth a twitching

nightjar. In her panic, she sings

in his mouth. He gives me her pain

like a gift, and I take it. I hear

the cries of her young, greedy with need,

expecting her return, but I don't let her go

until I get into the house. I read

the auspices-the way she flutters against

the wallpaper's moldy roses means

all can be lost. How she skims the ceiling

means a storm approaches. You should see

her in the beginnings of her fear, rushing

at the starless window, her body a dart,

her body the arrow of longing, aimed,

as all desperate things are, to crash

not into the object of desire,

but into the darkness behind it.

REGRET WITH WILDFLOWERS

So much can hide in a field. A prairie dog

can escape the hawk that devils it. A seed

can wait until it is ready to be broken open,

the earth ready to transform it. Today, aphids

ravage the wildflowers, bison graze in the pasture,

and I am returning home from another mistake.

Of all my minor regrets, this is the worst-

I let you assure me that desire is like a boy

who throws rocks at a deer decaying in the river.

That innocent. That brutal. I let you hold me down,

let you draw my blood to the surface of my skin

and call it an accident. But now I see how awful

the sky is. How stark. How bare. How, when clouds

expose the sun, horses tilt their heads with pleasure.

DISCIPLINE WITH LINES FROM FIRST CORINTHIANS

You try and teach me to be careful with my thoughts

or else, when the day comes, my ashes may not ascend

with the rest of the believers, but I can't help myself.

I'm shy and susceptible to voices stirring in the clock

at midnight whispering Listen, I tell you a mystery:

we will not all sleep, but we will all be changed.

You say it is not the animal in us that loves to struggle,

but the spirit that wants to be locked in the crucible

of flesh until the soul burns clean. Mother, I beat my body

and make it my slave. I see a snake swallow its tail and know

we are all infinite. Father, take me to the field where snow

is melting through the ribs of the deer it covered all winter.

There is a word inside every perishable thing aching

to be spoken so it may live again. I've heard it.

I found a bunting drowsing in the bushes, pinned back

its wings and listened to its indigo lullaby, its song

like last century's wind asking How can some of you say

there is no resurrection? How could any of us be damned?

COME BACK TO ME

If you go to the ruins, a man will sell you

the story of a queen for a kiss. This is the commerce

of beauty. His lips. Your imagination. A moment

of closed eyes and forgetting. He will tell you

it is good luck to take your husband and lay him

down on a tomb for a night, but when you say

you're alone, he insists that this is better-

to lay yourself down under a fire that has no heat

and pray to the Tunisian moon for a barren orchard

and an ocean without sharks. There is comfort

in a lie, but there is also a thief who will take you

unarmed in a dark town asking only for a kiss

and the money in your wallet. And you will

give it. Freely. Because a man asked for part of you,

and because you've been alone for so long

you've forgotten what a man tastes like.

Because it's your last night in Africa and twelve

dollars is not too much to lose. Because he says

Come back to me even as you are showing him

your breasts in the cemetery, and because, in truth,

you like the way the moonlight looks on his skin.

Cuprins

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Prayer for Deeper Water

1. (n) A colony of rooks

Aubade with a Broken Neck

Aubade with a Fox and a Birthmark

Dueling Sonnets on the Railroad Tracks

Aubade in Which the Bats Tried to Warn Me

Aubade in Which I Untangle Her Hair

Oneiromancy

Aubade with a Panic of Hearts

Regret with Wildflowers

Concerning Cuttlefish and Ugolino

Appalachian Aubade

Restoration of the Saints

Noli Me Tangere

Requiem with Coal, Butterflies, and Terrible Angels

2. (n) A breeding place

Fiat Lux

Elegy with Mosquitoes, Peppermints, and a Snapping Turtle

The Summer after They Crashed and Drowned

Discipline with Lines from First Corinthians

To the Tall Stranger Who Kept His Hands in His Pockets, Fourteen Years Later

The Bullet Collector

Chastity Belt Lesson

On a Mission Trip to Philadelphia I Begin to Fear the Inside of My Body

Missionary Child

Possession

Glossolalia

Why He Leaves

Echolalia, St. Armands Key

Leviathan: A Rapture

Through a Glass Darkly

Prayer for Sunlight and Hunger

3. (n) A crowded tenement house

Ars Poetica

Nocturne with Clay Horses

Via Dolorosa

Falling (For the 146 . . . )

The Saints Go Marching

Battle Hymn

Falling (A twin-engined B-25 . . .)

At a Party on Ellis Island, Watching Fireworks

The Women Are Ordered to Clear the Bodies of Suitors Slain by Ulysses

Dressing Heads

Margaret Garner Explains It to Her Daughter

A Dead Woman Speaks to Her Resurrectionist

The Light in the Basement

Come Back to Me

American Pastoral

Kingdom Come

Nocturne with Oil Rigs and Jasmine

Prayer to Delay the Apocalypse

Acknowledgments

Prayer for Deeper Water

1. (n) A colony of rooks

Aubade with a Broken Neck

Aubade with a Fox and a Birthmark

Dueling Sonnets on the Railroad Tracks

Aubade in Which the Bats Tried to Warn Me

Aubade in Which I Untangle Her Hair

Oneiromancy

Aubade with a Panic of Hearts

Regret with Wildflowers

Concerning Cuttlefish and Ugolino

Appalachian Aubade

Restoration of the Saints

Noli Me Tangere

Requiem with Coal, Butterflies, and Terrible Angels

2. (n) A breeding place

Fiat Lux

Elegy with Mosquitoes, Peppermints, and a Snapping Turtle

The Summer after They Crashed and Drowned

Discipline with Lines from First Corinthians

To the Tall Stranger Who Kept His Hands in His Pockets, Fourteen Years Later

The Bullet Collector

Chastity Belt Lesson

On a Mission Trip to Philadelphia I Begin to Fear the Inside of My Body

Missionary Child

Possession

Glossolalia

Why He Leaves

Echolalia, St. Armands Key

Leviathan: A Rapture

Through a Glass Darkly

Prayer for Sunlight and Hunger

3. (n) A crowded tenement house

Ars Poetica

Nocturne with Clay Horses

Via Dolorosa

Falling (For the 146 . . . )

The Saints Go Marching

Battle Hymn

Falling (A twin-engined B-25 . . .)

At a Party on Ellis Island, Watching Fireworks

The Women Are Ordered to Clear the Bodies of Suitors Slain by Ulysses

Dressing Heads

Margaret Garner Explains It to Her Daughter

A Dead Woman Speaks to Her Resurrectionist

The Light in the Basement

Come Back to Me

American Pastoral

Kingdom Come

Nocturne with Oil Rigs and Jasmine

Prayer to Delay the Apocalypse

Recenzii

120Normal0falsefalsefalseEN-USX-NONEX-NONE

Brimhall's way is to dwell in that dark, no matter how painful, and learn to love both terror and mystery. Terror has value. That's why she wants to see an avalanche hurtling toward her, because terror brings "my soul to the surface of my body" ("Prayer for Sunlight and Hunger"). There are other ways to touch the soul; spirit "wants to be locked in the crucible of flesh until the soul burns clean" ("Discipline with Lines from First Corinthians"), but she does not believe that is what flesh is for. She wants doubt to ease the ecstatic fire.

The speaker understands why her husband/lover must leave her— because she is water, not fire: "Because she has a jungle inside her and two savage rivers. Because the flood season never left her." She lays herself bare; she is just too much. "When you flicked me, I could feel / how much you hated me. And you came. And I came twice" ("Aubade in Which the Bats Tried to Warn Me").

The beauty and brutality in Brimhall's poems also apply to landscapes. The lushness of a Mississippi summer, the brown waters of the Amazon, the smell of mud, taste of snakes, snapping turtles, bats, infected frogs, scorpions, macaws that mate for life: "If one dies, the other collapses its wings, plummets to earth" ("Why He Leaves").

In the end, Brimhall casts aside the missionary zeal that was part of her growing up years. She isn't waiting for the Messiah's return. Epiphanies are found in avocados, birds, pound cake and peaches, in ordinary wonders: "My Lord, my heart / is insatiable. Leave me / here among the ordinary wonders" ("Prayer for Sunlight and Hunger"). Ordinary wonders like Venice: "Tell me heaven will be like Venice—dirty, beautiful / and sinking" ("Prayer to Delay the Apocalypse").

It should be mentioned that this book contains five aubades (morning love songs, usually about lovers separating at dawn) as well as prayers, nocturnes, an elegy, and a requiem and four definitions of the noun rookery, which serve as mini "overtures" to the four sections of the book.

This doesn't make sense, and yet it does. As she says, our "best senses" include True and False. And at some level, it feels true to the nature of dogs and to men and women. It's all a "puggle," which sounds suspiciously close to "puzzle."

In "Relatively Long Arms," Malech is about as close as she gets to a "relationship" poem: "...brought him a present, unwrapped the itch / I made from scratch. Longing's been / a long time coming. Ask me f / we're nowhere yet. Earth? Old girl got / the spins...." The title of Malech's book, Say So, hints at what we can expect: who says so? Say "so." Because I say so. And so it is.

This is not to imply that Brimhall doesn't love language. On the contrary—her lines are fluid, written with precision and clarity, each word locked into place. Nor that beneath surface acrobatics Malech's poems don't bite or illuminate. They do. As much fun as they are, there's a lurking sadness putting on a brave face: "Today's / family is a mouthful: moth, farther, / bother, cistern. Look. There's / the orphan's orphan boarding a bus" ("Spectrum").

Malech is well aware that while the spotlight may shine on a tightrope walker performing without a net, overhead there is still the immense dark. The best defense is to "kiss furiously under the black mask of the sky" ("Body Language"). Her relationship with the dark is to poke fun at it, to stick out her tongue.

Each book, in its inimitable way, refuses to shy away from metaphysics. Brimhall's is suffused with religiosity. She says she doesn't believe in God, yet she defies Hirn every day. As for Malech, best not to be too greedy: "I dare not ask for fruition, rather, pray for fruit...." ("Body Language"). She has big dreams and big aspirations, but small hope. All she asks for is this: "God, grant me small changes." That would be quite sufficient.

These are not books to be read lightly , nor in one sitting. Rather, savor the imagery and the language: lush and fertile, gorgeous and grotesque. In Brimhall and Malech we have two 2 Pt-century American women poets representing diametrically opposed artistic camps, each with a distinct view on the relationship between poet and reader. A reader may be drawn to one, or the other, or both. Think Elizabeth Bishop and Gertrude Stein. Think Robert Frost and Wallace Stevens. Better yet, think nightingale and hummingbird.

OF NIGHTINGALES AND HUMMINGBIRDS By Barbara Goldberg

Traci Brimhall, Rookery, Southern Illinois University Press, 2010, 79 pages, paper.

Dora Malech, Say So, Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2011, 77 pages, paper.

Traci Brimhall and Dora Malech are two young women at the outset of their writing careers. Both have impeccable credentials. Brimhall, a former Jay C. and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute of Creative Writing, received the 2011 Barnard Women's Poetry Prize for Our Lady of the Ruins (forthcoming from W.W. Norton). Malech, with an MFA from the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop, was recently honored with a Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. Yet they are driven by opposing forces: Brimhall believes in the power of narrative and Malech in the power of sound.

Brimhall's poems have compelling narratives and complex characters. While merciless when it comes to her own nature, she is generous about the flaws in others. The question of motivation interests her. Malech' s poems take you on a joyride. She is more intrigued in the connection between river and rivet than between river and stream. Narrative is not just obscured, it is eclipsed. She's not after insight. She's after insurrection.

Traci Brimhall's poems will split your breastbone and break your heart. They are that beautiful, that brutal. Her book Rookery opens this way: "Come back to bed,... I won't hurt you" ("Prayer for Deeper Water"). She then proceeds to hurt us by exposing the cruelty and grief residing in the human heart. These words of seduction and warning, I won't hurt you, test our willingness to enter a world where fear and mystery, terror and beauty, engage in a mighty struggle for our souls.

Traci Brimhall, Rookery, Southern Illinois University Press, 2010, 79 pages, paper.

Dora Malech, Say So, Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2011, 77 pages, paper.

Traci Brimhall and Dora Malech are two young women at the outset of their writing careers. Both have impeccable credentials. Brimhall, a former Jay C. and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute of Creative Writing, received the 2011 Barnard Women's Poetry Prize for Our Lady of the Ruins (forthcoming from W.W. Norton). Malech, with an MFA from the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop, was recently honored with a Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. Yet they are driven by opposing forces: Brimhall believes in the power of narrative and Malech in the power of sound.

Brimhall's poems have compelling narratives and complex characters. While merciless when it comes to her own nature, she is generous about the flaws in others. The question of motivation interests her. Malech' s poems take you on a joyride. She is more intrigued in the connection between river and rivet than between river and stream. Narrative is not just obscured, it is eclipsed. She's not after insight. She's after insurrection.

Traci Brimhall's poems will split your breastbone and break your heart. They are that beautiful, that brutal. Her book Rookery opens this way: "Come back to bed,... I won't hurt you" ("Prayer for Deeper Water"). She then proceeds to hurt us by exposing the cruelty and grief residing in the human heart. These words of seduction and warning, I won't hurt you, test our willingness to enter a world where fear and mystery, terror and beauty, engage in a mighty struggle for our souls.

The husband/lover responds by stating that he hates all women, except those "who've never heard / the frightened, wingless birds / / in their chests singing so they may be found" ("Prayer for Deeper Water")-- in short, women who do not know terror. Brimhall's speaker is well acquainted with terror: she absorbs it the way the color black absorbs light. She doesn't wear it lightly, unlike "the other woman," who sports a chrysanthemum tattoo on her lower back, and whose "dress slid from her body like smoke." The speaker is beyond feeling betrayed. "I make you tell me / how her pleasure sounded—a fox with its paw / in a trap's jaw „ „" And again, "I want to stroke her curls with you. „ ." And more: "I let you kiss me so I can get close enough to find her / smell on your body" ("Aubade with a Fox and a Birthmark").

The other woman is not the enemy—it's that the man, struggling for salvation, believes sex can bring him closer to God. "You think sex is a sacrament, the host / / in your mouth. Blood on your tongue" ("Aubade with a Fox and a Birthmark"). But the speaker has no need for his kind of God. She doesn't need to travel so far: "Even the shape of your mouth is a miracle, even your two bruised eyes." She accepts his bruises, his suffering, without being overwhelmed. "Forget all the women who've summered under you," she says. They provide a pleasure almost weightless. They are not burdened by the heavy baggage of grief. Instead, she exhorts him to walk back into the darkness "you were broken from" ("Prayer for Deeper Water").

Brimhall writes "broken from," not 'born from." We are all broken and broken from the primordial dark, the chaos that existed before creation—we are part of it, the darkness that preceded the light that split the world in two. For Brimhall, darkness is holy, holier than God. It is rich with possibility. It is "the darkness you guard, which is also the darkness / you're scared of, which is the same darkness in the heart's 1/ unfurnished rooms" ("Nocturne with Clay Horses"). It is the kind of dark that is the origin of the music Emily Dickinson refers to in "Split the lark ."

The other woman is not the enemy—it's that the man, struggling for salvation, believes sex can bring him closer to God. "You think sex is a sacrament, the host / / in your mouth. Blood on your tongue" ("Aubade with a Fox and a Birthmark"). But the speaker has no need for his kind of God. She doesn't need to travel so far: "Even the shape of your mouth is a miracle, even your two bruised eyes." She accepts his bruises, his suffering, without being overwhelmed. "Forget all the women who've summered under you," she says. They provide a pleasure almost weightless. They are not burdened by the heavy baggage of grief. Instead, she exhorts him to walk back into the darkness "you were broken from" ("Prayer for Deeper Water").

Brimhall writes "broken from," not 'born from." We are all broken and broken from the primordial dark, the chaos that existed before creation—we are part of it, the darkness that preceded the light that split the world in two. For Brimhall, darkness is holy, holier than God. It is rich with possibility. It is "the darkness you guard, which is also the darkness / you're scared of, which is the same darkness in the heart's 1/ unfurnished rooms" ("Nocturne with Clay Horses"). It is the kind of dark that is the origin of the music Emily Dickinson refers to in "Split the lark ."

Brimhall's way is to dwell in that dark, no matter how painful, and learn to love both terror and mystery. Terror has value. That's why she wants to see an avalanche hurtling toward her, because terror brings "my soul to the surface of my body" ("Prayer for Sunlight and Hunger"). There are other ways to touch the soul; spirit "wants to be locked in the crucible of flesh until the soul burns clean" ("Discipline with Lines from First Corinthians"), but she does not believe that is what flesh is for. She wants doubt to ease the ecstatic fire.

The speaker understands why her husband/lover must leave her— because she is water, not fire: "Because she has a jungle inside her and two savage rivers. Because the flood season never left her." She lays herself bare; she is just too much. "When you flicked me, I could feel / how much you hated me. And you came. And I came twice" ("Aubade in Which the Bats Tried to Warn Me").

The beauty and brutality in Brimhall's poems also apply to landscapes. The lushness of a Mississippi summer, the brown waters of the Amazon, the smell of mud, taste of snakes, snapping turtles, bats, infected frogs, scorpions, macaws that mate for life: "If one dies, the other collapses its wings, plummets to earth" ("Why He Leaves").

In the end, Brimhall casts aside the missionary zeal that was part of her growing up years. She isn't waiting for the Messiah's return. Epiphanies are found in avocados, birds, pound cake and peaches, in ordinary wonders: "My Lord, my heart / is insatiable. Leave me / here among the ordinary wonders" ("Prayer for Sunlight and Hunger"). Ordinary wonders like Venice: "Tell me heaven will be like Venice—dirty, beautiful / and sinking" ("Prayer to Delay the Apocalypse").

It should be mentioned that this book contains five aubades (morning love songs, usually about lovers separating at dawn) as well as prayers, nocturnes, an elegy, and a requiem and four definitions of the noun rookery, which serve as mini "overtures" to the four sections of the book.

If Traci Brirnhall's poems burrow in the dark to find gold, Dora Malech's play hopscotch all day long. Take "Love Poem": here she is sweet-talking her lover, calling him a "one-trick pony to my one-horse town, / ...my one-stop-shopping, my space heater, / juke joint, tourist trap, my peep show, my meter-reader...." And Malech is just warming up:

Tell me you'll dismember this night forever, you my punch-drunldng bag, tar to my feather.

More than the sum of our private parts, we are some peekaboo, some peak and valley, some

bright equation (if end then but, if er then oh). My fruit bat, my gewgaw. You had me at no dub.

Dismember this night forever? The sum of our private parts? My gewgaw? Malech has a ball with the language. And she throws it in our court. Her craft is crafty—her wit anything by witless.

And she has perfect pitch. Try reading some of Matech' s poems aloud for the sheer pleasure of it -the rhythms are staccato, the music pizzicato. Her words jump off the tongue—which, by the way, can be found "behind the deli counter" ("Some Speech").

Malech's words aren't arranged in an arbitrary manner. Her associations are based on sound, juxtapositions, point-counterpoint, on puns. Here is Malech defining a poem as a "pound puppy / whimpering for love" ("Some Speech"). There's truth in that statement, but it's told slant. In "Lying Down with Dogs," Malech riffs some more on doggy imagery:

Miss stay, miss beg. Mistake the clock's tick-tock for some synecdochetic-tocking heart. No such touch as specious scratch of scruff or tummy. Name the litter after our best senses Salty, Sweet, Sour, True and False. Lexiconic misprojections, good is good for ours and only, subspurious as in—if that's a puggle, my Grandpa's a cockapoo. Grandma's a labradoodle.

Tell me you'll dismember this night forever, you my punch-drunldng bag, tar to my feather.

More than the sum of our private parts, we are some peekaboo, some peak and valley, some

bright equation (if end then but, if er then oh). My fruit bat, my gewgaw. You had me at no dub.

Dismember this night forever? The sum of our private parts? My gewgaw? Malech has a ball with the language. And she throws it in our court. Her craft is crafty—her wit anything by witless.

And she has perfect pitch. Try reading some of Matech' s poems aloud for the sheer pleasure of it -the rhythms are staccato, the music pizzicato. Her words jump off the tongue—which, by the way, can be found "behind the deli counter" ("Some Speech").

Malech's words aren't arranged in an arbitrary manner. Her associations are based on sound, juxtapositions, point-counterpoint, on puns. Here is Malech defining a poem as a "pound puppy / whimpering for love" ("Some Speech"). There's truth in that statement, but it's told slant. In "Lying Down with Dogs," Malech riffs some more on doggy imagery:

Miss stay, miss beg. Mistake the clock's tick-tock for some synecdochetic-tocking heart. No such touch as specious scratch of scruff or tummy. Name the litter after our best senses Salty, Sweet, Sour, True and False. Lexiconic misprojections, good is good for ours and only, subspurious as in—if that's a puggle, my Grandpa's a cockapoo. Grandma's a labradoodle.

This doesn't make sense, and yet it does. As she says, our "best senses" include True and False. And at some level, it feels true to the nature of dogs and to men and women. It's all a "puggle," which sounds suspiciously close to "puzzle."

In "Relatively Long Arms," Malech is about as close as she gets to a "relationship" poem: "...brought him a present, unwrapped the itch / I made from scratch. Longing's been / a long time coming. Ask me f / we're nowhere yet. Earth? Old girl got / the spins...." The title of Malech's book, Say So, hints at what we can expect: who says so? Say "so." Because I say so. And so it is.

This is not to imply that Brimhall doesn't love language. On the contrary—her lines are fluid, written with precision and clarity, each word locked into place. Nor that beneath surface acrobatics Malech's poems don't bite or illuminate. They do. As much fun as they are, there's a lurking sadness putting on a brave face: "Today's / family is a mouthful: moth, farther, / bother, cistern. Look. There's / the orphan's orphan boarding a bus" ("Spectrum").

Malech is well aware that while the spotlight may shine on a tightrope walker performing without a net, overhead there is still the immense dark. The best defense is to "kiss furiously under the black mask of the sky" ("Body Language"). Her relationship with the dark is to poke fun at it, to stick out her tongue.

Each book, in its inimitable way, refuses to shy away from metaphysics. Brimhall's is suffused with religiosity. She says she doesn't believe in God, yet she defies Hirn every day. As for Malech, best not to be too greedy: "I dare not ask for fruition, rather, pray for fruit...." ("Body Language"). She has big dreams and big aspirations, but small hope. All she asks for is this: "God, grant me small changes." That would be quite sufficient.

"This emotionally articulate, intense debut gives us the myth of self in its various incarnations: elegiac, surreal, meditative, erotic, dreamlike. I love [Brimhall's] luscious verbal texturing and lyric slipperiness, an assertive voice, a sensuality, a glow. A beautiful book." -Ilya Kaminsky, author of Dancing in Odessa

"The poems in Traci Brimhall's Rookery make beautiful the brutal as she casts an uncompromising eye on the vagaries of faith, the disappointments of the human heart-and the uneasy interstices between animal consciousness and ours. . . . Part incantation, part lamentation, the language in these poems is sensual and urgent." -Claudia Emerson, author of Figure Studies: Poems