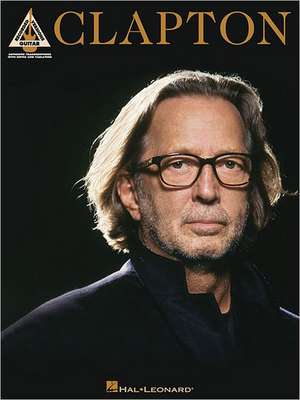

Clapton: Guitar Recorded Versions

Compozitor Eric Claptonen Limba Engleză Paperback – apr 2011

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 100.65 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| BROADWAY BOOKS – 31 mai 2008 | 100.65 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation – apr 2011 | 138.01 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Din seria Guitar Recorded Versions

-

Preț: 152.75 lei

Preț: 152.75 lei -

Preț: 143.71 lei

Preț: 143.71 lei -

Preț: 140.37 lei

Preț: 140.37 lei -

Preț: 178.36 lei

Preț: 178.36 lei -

Preț: 186.67 lei

Preț: 186.67 lei -

Preț: 192.93 lei

Preț: 192.93 lei -

Preț: 172.33 lei

Preț: 172.33 lei -

Preț: 145.12 lei

Preț: 145.12 lei -

Preț: 173.59 lei

Preț: 173.59 lei -

Preț: 162.21 lei

Preț: 162.21 lei -

Preț: 153.91 lei

Preț: 153.91 lei -

Preț: 115.19 lei

Preț: 115.19 lei -

Preț: 127.05 lei

Preț: 127.05 lei -

Preț: 140.65 lei

Preț: 140.65 lei -

Preț: 137.95 lei

Preț: 137.95 lei -

Preț: 231.75 lei

Preț: 231.75 lei -

Preț: 113.22 lei

Preț: 113.22 lei -

Preț: 141.86 lei

Preț: 141.86 lei -

Preț: 160.89 lei

Preț: 160.89 lei -

Preț: 140.82 lei

Preț: 140.82 lei -

Preț: 133.78 lei

Preț: 133.78 lei -

Preț: 93.15 lei

Preț: 93.15 lei -

Preț: 109.82 lei

Preț: 109.82 lei -

Preț: 171.95 lei

Preț: 171.95 lei -

Preț: 140.00 lei

Preț: 140.00 lei -

Preț: 109.84 lei

Preț: 109.84 lei -

Preț: 112.18 lei

Preț: 112.18 lei -

Preț: 145.59 lei

Preț: 145.59 lei -

Preț: 161.04 lei

Preț: 161.04 lei -

Preț: 191.54 lei

Preț: 191.54 lei -

Preț: 221.03 lei

Preț: 221.03 lei -

Preț: 145.57 lei

Preț: 145.57 lei -

Preț: 123.31 lei

Preț: 123.31 lei -

Preț: 183.09 lei

Preț: 183.09 lei -

Preț: 166.81 lei

Preț: 166.81 lei -

Preț: 142.91 lei

Preț: 142.91 lei -

Preț: 133.19 lei

Preț: 133.19 lei -

Preț: 166.58 lei

Preț: 166.58 lei -

Preț: 159.59 lei

Preț: 159.59 lei -

Preț: 165.76 lei

Preț: 165.76 lei -

Preț: 116.57 lei

Preț: 116.57 lei -

Preț: 124.73 lei

Preț: 124.73 lei -

Preț: 106.14 lei

Preț: 106.14 lei -

Preț: 123.85 lei

Preț: 123.85 lei -

Preț: 157.71 lei

Preț: 157.71 lei -

Preț: 125.56 lei

Preț: 125.56 lei -

Preț: 95.32 lei

Preț: 95.32 lei -

Preț: 126.59 lei

Preț: 126.59 lei

Preț: 138.01 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 207

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.41€ • 27.66$ • 21.89£

26.41€ • 27.66$ • 21.89£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 18 martie-01 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781617741760

ISBN-10: 1617741760

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 230 x 304 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation

Colecția Guitar Recorded Versions

Seria Guitar Recorded Versions

ISBN-10: 1617741760

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 230 x 304 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation

Colecția Guitar Recorded Versions

Seria Guitar Recorded Versions

Notă biografică

ERIC CLAPTON is married to Melia McEnery and is the father of four daughters. He lives outside London.

Extras

Growing Up

Early in my childhood, when I was about six or seven, I began to get the feeling that there was something different about me. Maybe it was the way people talked about me as if I weren’t in the room. My family lived at 1, the Green, a tiny house in Ripley, Surrey, which opened directly onto the village Green. It was part of what had once been almshouses and was divided into four rooms; two poky bedrooms upstairs, and a small front room and kitchen downstairs. The toilet was outside, in a corrugated iron shed at the bottom of the garden, and we had no bathtub, just a big zinc basin that hung on the back door. I don’t remember ever using it.

Twice a week my mum used to fill a smaller tin tub with water and sponge me down, and on Sunday afternoons I used to go and have a bath at my Auntie Audrey’s, my dad’s sister, who lived in the new flats on the main road. I lived with Mum and Dad, who slept in the main bedroom overlooking the Green, and my brother, Adrian, who had a room at the back. I slept on a camp bed, sometimes with my parents, sometimes downstairs, depending on who was staying at the time. The house had no electricity, and the gas lamps made a constant hissing sound. It amazes me now to think that whole families lived in these little houses.

My mum had six sisters: Nell, Elsie, Renie, Flossie, Cath, and Phyllis, and two brothers, Joe and Jack. On a Sunday it wasn’t unusual for two or three of these families to show up, and they would pass the gossip and get up–to–date with what was happening with us and with them. In the smallness of this house, conversations were always being carried on in front of me as if I didn’t exist, with whispers exchanged between the sisters. It was a house full of secrets. But bit by bit, by carefully listening to these exchanges, I slowly began to put together a picture of what was going on and to understand that the secrets were usually to do with me. One day I heard one of my aunties ask, “Have you heard from his mum?” and the truth dawned on me, that when Uncle Adrian jokingly called me a little bastard, he was telling the truth.

The full impact of this realization upon me was traumatic, because at the time I was born, in March 1945—in spite of the fact that it had become so common because of the large number of overseas soldiers and airmen passing through England—an enormous stigma was still attached to illegitimacy. Though this was true across the class divide, it was particularly so among working–class families such as ours, who, living in a small village community, knew little of the luxury of privacy. Because of this, I became intensely confused about my position, and alongside my deep feelings of love for my family there existed a suspicion that in a tiny place like Ripley, I might be an embarrassment to them that they always had to explain.

The truth I eventually discovered was that Mum and Dad, Rose and Jack Clapp, were in fact my grandparents, Adrian was my uncle, and Rose’s daughter, Patricia, from an earlier marriage, was my real mother and had given me the name Clapton. In the mid–1920s, Rose Mitchell, as she was then, had met and fallen in love with Reginald Cecil Clapton, known as Rex, the dashing and handsome, Oxford–educated son of an Indian army officer. They had married in February 1927, much against the wishes of his parents, who considered that Rex was marrying beneath him. The wedding took place a few weeks after Rose had given birth to their first child, my uncle Adrian. They set up home in Woking, but sadly, it was a short–lived marriage, as Rex died of consumption in 1932, three years after the birth of their second child, Patricia.

Rose was heartbroken. She returned to Ripley, and it was ten years before she was married again, after a long courtship on his part, to Jack Clapp, a master plasterer. They were married in 1942, and Jack, who as a child had badly injured his leg and therefore been exempt from call–up, found himself stepfather to Adrian and Patricia. In 1944, like many other towns in the south of England, Ripley found itself inundated with troops from the United States and Canada, and at some point Pat, age fifteen, enjoyed a brief affair with Edward Fryer, a Canadian airman stationed nearby. They had met at a dance where he was playing the piano in the band. He turned out to be married, so when she found out she was pregnant, she had to cope on her own. Rose and Jack protected her, and I was born secretly in the upstairs back bedroom of their house on March 30, 1945. As soon as it was practical, when I was in my second year, Pat left Ripley, and my grandparents brought me up as their own child. I was named Eric, but Ric was what they all called me.

Rose was petite with dark hair and sharp, delicate features, with a characteristic pointed nose, “the Mitchell nose,” as it was known in the family and which was inherited from her father, Jack Mitchell. Photographs of her as a young woman show her to have been very pretty, quite the beauty among her sisters. But at some point at the outset of the war, when she had just turned thirty, she underwent surgery for a serious problem with her palate. During the operation there was a power cut that resulted in the surgery having to be abandoned, leaving her with a massive scar underneath her left cheekbone that gave the impression that a piece of her cheek had been hollowed out. This left her with a certain amount of self-consciousness. In his song “Not Dark Yet,” Dylan wrote, “Behind every beautiful face there’s been some kind of pain.” Her suffering made her a very warm person with a deep compassion for other people's dilemmas. She was the focus of my life for much of my upbringing.

Jack, her second husband and the love of her life, was four years younger than Rose. A shy, handsome man, over six feet tall with strong features and very well built, he had a look of Lee Marvin about him and used to smoke his own roll–ups, made from a strong, dark tobacco called Black Beauty. He was authoritarian, as fathers were in those days, but he was kind, and very affectionate to me in his way, especially in my infant years. We didn’t have a very tactile relationship, as all the men in our family found it hard to express feelings of affection or warmth. Perhaps it was considered a sign of weakness. Jack made his living as a master plasterer, working for a local building contractor. He was a master carpenter and a master bricklayer, too, so he could actually build an entire house on his own.

An extremely conscientious man with a very strong work ethic, he brought in a very steady wage, which didn’t ever fluctuate for the whole time I was growing up, so although we could have been considered poor, we rarely had a shortage of money. When things occasionally did get tight, Rose would go out and clean other people’s houses, or work part–time at Stansfield’s, a bottling company with a factory on the outskirts of the village that produced fizzy drinks such as lemonade, orangeade, and cream soda. When I was older I used to do holiday jobs there, sticking on labels and helping with deliveries, to earn pocket money. The factory was like something out of Dickens, reminiscent of a workhouse, with rats running around and a fierce bull terrier that they kept locked up so it wouldn’t attack visitors.

Ripley, which is more like a suburb today, was deep in the country when I was born. It was a typical small rural community, with most of the residents being agricultural workers, and if you weren’t careful about what you said, then everybody knew your business. So it was important to be polite. Guildford was the main shopping town, which you could get to by bus, but Ripley had its own shops, too. There were two butchers, Conisbee’s and Russ’s, and two bakeries, Weller’s and Collins’s, a grocer’s, Jack Richardson’s, Green’s the paper shop, Noakes the ironmonger, a fish–and–chip shop, and five pubs. King and Olliers was the haberdashers where I got my first pair of long trousers, and it doubled as a post office, and we had a blacksmith where all the local farm horses came in for shoes.

Every village had a sweet shop; ours was run by two old-fashioned sisters, the Miss Farrs. We would go in there and the bell would go ding–a–ling–a–ling, and one of them would take so long to come out from the back of the shop that we could fill our pockets up before a movement of the curtain told us she was about to appear. I would buy two Sherbert Dabs or a few Flying Saucers, using the family ration book, and walk out with a pocketful of Horlicks or Ovaltine tablets, which had become my first addiction.

In spite of the fact that Ripley was, all in all, a happy place to grow up in, life was soured by what I had found out about my origins. The result was that I began to withdraw into myself. There seemed to have been some definite choices made within my family regarding how to deal with my circumstances, and I was not made privy to any of them. I observed the code of secrecy that existed in the house—“We don’t talk about what went on”—and there was also a strong disciplinarian authority in the household, which made me nervous about asking any questions. On reflection, it occurs to me that the family had no real idea of how to explain my own existence to me, and that the guilt attached to that made them very aware of their own shortcomings, which would go a long way in explaining the anger and awkwardness that my presence aroused in almost everybody. As a result I attached myself to the family dog, a black Labrador called Prince, and created a character for myself, whose name was “Johnny Malingo.” Johnny was a suave, devil–may–care man/boy of the world who rode roughshod over anyone who got in his way. I would escape into Johnny when things got too much for me, and stay there until the storm had passed. I also invented a fantasy friend called Bushbranch, a small horse who went with me everywhere. Sometimes Johnny would magically become a cowboy and climb onto Bushbranch, and together they would ride off into the sunset. At the same time, I started to draw quite obsessively. My first fascination was with pies. A man used to come to the village Green pushing a barrow, which was his container for hot pies. I had always loved pies—Rose was an excellent cook—and I produced hundreds of drawings of them and of the pie man. Then I turned to copying from comics.

Because I was illegitimate, Rose and Jack tended to spoil me. Jack actually made my toys for me. I remember, for example, a beautiful sword and shield that he made me by hand. It was the envy of all the other kids. Rose bought me all the comics I wanted. I seemed to get a different one every day, always The Topper, The Dandy, The Eagle, and The Beano. I particularly loved the Bash Street Kids, and I always used to notice when the artists would change and Lord Snooty’s top hat would be different in some way. Over the years I copied countless drawings from these comics—cowboys and Indians, Romans, gladiators, and knights in armor. Sometimes at school I did no classwork at all, and it became quite normal to see all of my textbooks full of nothing but drawings.

School for me began when I was five, at Ripley Church of England Primary School, which was situated in a flint building next to the village church. Opposite was the village hall, where I attended Sunday school, and where I first heard a lot of the old, beautiful English hymns, my favorite of which was “Jesus Bids Us Shine.” At first I was quite happy going to school. Most of the kids who lived on the Green next to us started at the same time, but as the months went by, and it dawned on me that this was it for the long haul, I began to panic. The feelings of insecurity I had about my home life made me hate school. All I wanted to be was anonymous, which kept me out of entering any kind of competitive event. I hated anything that would single me out and get me unwanted attention.

I also felt that sending me to school was just a way of getting me out of the house, and I became very resentful. One master, quite young, a Mr. Porter, seemed to have a real interest in unearthing the children's gifts or skills, and becoming acquainted with us in general. Whenever he tried this with me, I would become extremely resentful. I would stare at him with as much hatred as I could muster, until he eventually caned me for what he called “dumb insolence.” I don’t blame him now; anyone in a position of authority got that kind of treatment from me. Art was the only subject that I really enjoyed, though I did win an award for playing “Greensleeves” on the recorder, which was the first instrument I ever learned to play.

The headmaster, Mr. Dickson, was a Scotsman with a shock of red hair. I had very little to do with him until I was nine years old, when I was called up before him for making a lewd suggestion to one of the girls in my class. While playing on the Green, I had come across a piece of homemade pornography lying in the grass. It was a kind of book, made of pieces of paper crudely stapled together with rather amateurish drawings of genitalia and a typed text full of words I had never heard of. My curiosity was aroused because I hadn’t had any kind of sex education, and I had certainly never seen a woman’s genitalia. In fact, I wasn't even certain if boys were different from girls until I saw this book.

Once I recovered from the shock of seeing these drawings, I was determined to find out about girls. I was too shy to ask any of the girls I knew at school, but there was this new girl in class, and because she was new, it was open season on her. As luck would have it, she was put at the desk directly in front of me in the classroom, so one morning I plucked up courage and asked her, without any idea of what the words meant, “Do you fancy a shag?” She looked at me with a bemused expression, because she obviously didn’t have a clue what I was talking about, but at playtime she went and told another girl what I’d said, and asked what it meant. After lunch I was summoned to the headmaster’s office, where, after being quizzed as to exactly what I had said to her and being made to promise to apologize, I was bent over and given six of the best. I left in tears, and the whole episode had a dreadful effect on me, as from that point on I tended to associate sex with punishment, shame, and embarrassment, feelings that colored my sexual life for years.

From the Hardcover edition.

Early in my childhood, when I was about six or seven, I began to get the feeling that there was something different about me. Maybe it was the way people talked about me as if I weren’t in the room. My family lived at 1, the Green, a tiny house in Ripley, Surrey, which opened directly onto the village Green. It was part of what had once been almshouses and was divided into four rooms; two poky bedrooms upstairs, and a small front room and kitchen downstairs. The toilet was outside, in a corrugated iron shed at the bottom of the garden, and we had no bathtub, just a big zinc basin that hung on the back door. I don’t remember ever using it.

Twice a week my mum used to fill a smaller tin tub with water and sponge me down, and on Sunday afternoons I used to go and have a bath at my Auntie Audrey’s, my dad’s sister, who lived in the new flats on the main road. I lived with Mum and Dad, who slept in the main bedroom overlooking the Green, and my brother, Adrian, who had a room at the back. I slept on a camp bed, sometimes with my parents, sometimes downstairs, depending on who was staying at the time. The house had no electricity, and the gas lamps made a constant hissing sound. It amazes me now to think that whole families lived in these little houses.

My mum had six sisters: Nell, Elsie, Renie, Flossie, Cath, and Phyllis, and two brothers, Joe and Jack. On a Sunday it wasn’t unusual for two or three of these families to show up, and they would pass the gossip and get up–to–date with what was happening with us and with them. In the smallness of this house, conversations were always being carried on in front of me as if I didn’t exist, with whispers exchanged between the sisters. It was a house full of secrets. But bit by bit, by carefully listening to these exchanges, I slowly began to put together a picture of what was going on and to understand that the secrets were usually to do with me. One day I heard one of my aunties ask, “Have you heard from his mum?” and the truth dawned on me, that when Uncle Adrian jokingly called me a little bastard, he was telling the truth.

The full impact of this realization upon me was traumatic, because at the time I was born, in March 1945—in spite of the fact that it had become so common because of the large number of overseas soldiers and airmen passing through England—an enormous stigma was still attached to illegitimacy. Though this was true across the class divide, it was particularly so among working–class families such as ours, who, living in a small village community, knew little of the luxury of privacy. Because of this, I became intensely confused about my position, and alongside my deep feelings of love for my family there existed a suspicion that in a tiny place like Ripley, I might be an embarrassment to them that they always had to explain.

The truth I eventually discovered was that Mum and Dad, Rose and Jack Clapp, were in fact my grandparents, Adrian was my uncle, and Rose’s daughter, Patricia, from an earlier marriage, was my real mother and had given me the name Clapton. In the mid–1920s, Rose Mitchell, as she was then, had met and fallen in love with Reginald Cecil Clapton, known as Rex, the dashing and handsome, Oxford–educated son of an Indian army officer. They had married in February 1927, much against the wishes of his parents, who considered that Rex was marrying beneath him. The wedding took place a few weeks after Rose had given birth to their first child, my uncle Adrian. They set up home in Woking, but sadly, it was a short–lived marriage, as Rex died of consumption in 1932, three years after the birth of their second child, Patricia.

Rose was heartbroken. She returned to Ripley, and it was ten years before she was married again, after a long courtship on his part, to Jack Clapp, a master plasterer. They were married in 1942, and Jack, who as a child had badly injured his leg and therefore been exempt from call–up, found himself stepfather to Adrian and Patricia. In 1944, like many other towns in the south of England, Ripley found itself inundated with troops from the United States and Canada, and at some point Pat, age fifteen, enjoyed a brief affair with Edward Fryer, a Canadian airman stationed nearby. They had met at a dance where he was playing the piano in the band. He turned out to be married, so when she found out she was pregnant, she had to cope on her own. Rose and Jack protected her, and I was born secretly in the upstairs back bedroom of their house on March 30, 1945. As soon as it was practical, when I was in my second year, Pat left Ripley, and my grandparents brought me up as their own child. I was named Eric, but Ric was what they all called me.

Rose was petite with dark hair and sharp, delicate features, with a characteristic pointed nose, “the Mitchell nose,” as it was known in the family and which was inherited from her father, Jack Mitchell. Photographs of her as a young woman show her to have been very pretty, quite the beauty among her sisters. But at some point at the outset of the war, when she had just turned thirty, she underwent surgery for a serious problem with her palate. During the operation there was a power cut that resulted in the surgery having to be abandoned, leaving her with a massive scar underneath her left cheekbone that gave the impression that a piece of her cheek had been hollowed out. This left her with a certain amount of self-consciousness. In his song “Not Dark Yet,” Dylan wrote, “Behind every beautiful face there’s been some kind of pain.” Her suffering made her a very warm person with a deep compassion for other people's dilemmas. She was the focus of my life for much of my upbringing.

Jack, her second husband and the love of her life, was four years younger than Rose. A shy, handsome man, over six feet tall with strong features and very well built, he had a look of Lee Marvin about him and used to smoke his own roll–ups, made from a strong, dark tobacco called Black Beauty. He was authoritarian, as fathers were in those days, but he was kind, and very affectionate to me in his way, especially in my infant years. We didn’t have a very tactile relationship, as all the men in our family found it hard to express feelings of affection or warmth. Perhaps it was considered a sign of weakness. Jack made his living as a master plasterer, working for a local building contractor. He was a master carpenter and a master bricklayer, too, so he could actually build an entire house on his own.

An extremely conscientious man with a very strong work ethic, he brought in a very steady wage, which didn’t ever fluctuate for the whole time I was growing up, so although we could have been considered poor, we rarely had a shortage of money. When things occasionally did get tight, Rose would go out and clean other people’s houses, or work part–time at Stansfield’s, a bottling company with a factory on the outskirts of the village that produced fizzy drinks such as lemonade, orangeade, and cream soda. When I was older I used to do holiday jobs there, sticking on labels and helping with deliveries, to earn pocket money. The factory was like something out of Dickens, reminiscent of a workhouse, with rats running around and a fierce bull terrier that they kept locked up so it wouldn’t attack visitors.

Ripley, which is more like a suburb today, was deep in the country when I was born. It was a typical small rural community, with most of the residents being agricultural workers, and if you weren’t careful about what you said, then everybody knew your business. So it was important to be polite. Guildford was the main shopping town, which you could get to by bus, but Ripley had its own shops, too. There were two butchers, Conisbee’s and Russ’s, and two bakeries, Weller’s and Collins’s, a grocer’s, Jack Richardson’s, Green’s the paper shop, Noakes the ironmonger, a fish–and–chip shop, and five pubs. King and Olliers was the haberdashers where I got my first pair of long trousers, and it doubled as a post office, and we had a blacksmith where all the local farm horses came in for shoes.

Every village had a sweet shop; ours was run by two old-fashioned sisters, the Miss Farrs. We would go in there and the bell would go ding–a–ling–a–ling, and one of them would take so long to come out from the back of the shop that we could fill our pockets up before a movement of the curtain told us she was about to appear. I would buy two Sherbert Dabs or a few Flying Saucers, using the family ration book, and walk out with a pocketful of Horlicks or Ovaltine tablets, which had become my first addiction.

In spite of the fact that Ripley was, all in all, a happy place to grow up in, life was soured by what I had found out about my origins. The result was that I began to withdraw into myself. There seemed to have been some definite choices made within my family regarding how to deal with my circumstances, and I was not made privy to any of them. I observed the code of secrecy that existed in the house—“We don’t talk about what went on”—and there was also a strong disciplinarian authority in the household, which made me nervous about asking any questions. On reflection, it occurs to me that the family had no real idea of how to explain my own existence to me, and that the guilt attached to that made them very aware of their own shortcomings, which would go a long way in explaining the anger and awkwardness that my presence aroused in almost everybody. As a result I attached myself to the family dog, a black Labrador called Prince, and created a character for myself, whose name was “Johnny Malingo.” Johnny was a suave, devil–may–care man/boy of the world who rode roughshod over anyone who got in his way. I would escape into Johnny when things got too much for me, and stay there until the storm had passed. I also invented a fantasy friend called Bushbranch, a small horse who went with me everywhere. Sometimes Johnny would magically become a cowboy and climb onto Bushbranch, and together they would ride off into the sunset. At the same time, I started to draw quite obsessively. My first fascination was with pies. A man used to come to the village Green pushing a barrow, which was his container for hot pies. I had always loved pies—Rose was an excellent cook—and I produced hundreds of drawings of them and of the pie man. Then I turned to copying from comics.

Because I was illegitimate, Rose and Jack tended to spoil me. Jack actually made my toys for me. I remember, for example, a beautiful sword and shield that he made me by hand. It was the envy of all the other kids. Rose bought me all the comics I wanted. I seemed to get a different one every day, always The Topper, The Dandy, The Eagle, and The Beano. I particularly loved the Bash Street Kids, and I always used to notice when the artists would change and Lord Snooty’s top hat would be different in some way. Over the years I copied countless drawings from these comics—cowboys and Indians, Romans, gladiators, and knights in armor. Sometimes at school I did no classwork at all, and it became quite normal to see all of my textbooks full of nothing but drawings.

School for me began when I was five, at Ripley Church of England Primary School, which was situated in a flint building next to the village church. Opposite was the village hall, where I attended Sunday school, and where I first heard a lot of the old, beautiful English hymns, my favorite of which was “Jesus Bids Us Shine.” At first I was quite happy going to school. Most of the kids who lived on the Green next to us started at the same time, but as the months went by, and it dawned on me that this was it for the long haul, I began to panic. The feelings of insecurity I had about my home life made me hate school. All I wanted to be was anonymous, which kept me out of entering any kind of competitive event. I hated anything that would single me out and get me unwanted attention.

I also felt that sending me to school was just a way of getting me out of the house, and I became very resentful. One master, quite young, a Mr. Porter, seemed to have a real interest in unearthing the children's gifts or skills, and becoming acquainted with us in general. Whenever he tried this with me, I would become extremely resentful. I would stare at him with as much hatred as I could muster, until he eventually caned me for what he called “dumb insolence.” I don’t blame him now; anyone in a position of authority got that kind of treatment from me. Art was the only subject that I really enjoyed, though I did win an award for playing “Greensleeves” on the recorder, which was the first instrument I ever learned to play.

The headmaster, Mr. Dickson, was a Scotsman with a shock of red hair. I had very little to do with him until I was nine years old, when I was called up before him for making a lewd suggestion to one of the girls in my class. While playing on the Green, I had come across a piece of homemade pornography lying in the grass. It was a kind of book, made of pieces of paper crudely stapled together with rather amateurish drawings of genitalia and a typed text full of words I had never heard of. My curiosity was aroused because I hadn’t had any kind of sex education, and I had certainly never seen a woman’s genitalia. In fact, I wasn't even certain if boys were different from girls until I saw this book.

Once I recovered from the shock of seeing these drawings, I was determined to find out about girls. I was too shy to ask any of the girls I knew at school, but there was this new girl in class, and because she was new, it was open season on her. As luck would have it, she was put at the desk directly in front of me in the classroom, so one morning I plucked up courage and asked her, without any idea of what the words meant, “Do you fancy a shag?” She looked at me with a bemused expression, because she obviously didn’t have a clue what I was talking about, but at playtime she went and told another girl what I’d said, and asked what it meant. After lunch I was summoned to the headmaster’s office, where, after being quizzed as to exactly what I had said to her and being made to promise to apologize, I was bent over and given six of the best. I left in tears, and the whole episode had a dreadful effect on me, as from that point on I tended to associate sex with punishment, shame, and embarrassment, feelings that colored my sexual life for years.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Like the bluesmen who inspired him, Clapton has his share of scars . . . his compelling memoir is . . . a soulful performance.”

—People

“An absorbing tale of artistry, decadence, and redemption.”

—Los Angeles Times

“One of the very best rock autobiographies ever.”

— Houston Chronicle

“A glorious rock history.”

—New York Post

“This book does what many rock historians couldn’t: It debunks the legend . . . puts a lie to the glamour of what it means to be a rock star.”

—Greg Kot, Chicago Tribune

“Strong stuff. Clapton reveals its author’s journey to self-acceptance and manhood. Anyone who cares about the man and his music will want to take the trip with him.”

—Anthony DeCurtis, Rolling Stone

“Clapton is honest . . . even searing and often witty, with a hard-won survivor’s humor . . . an honorable badge of a book.”

—Stephen King, New York Times Book Review

“Riveting”

—Boston Herald

“An even, unblinking sensibility defines the author’s voice.”

—New York Times

“An unsparing self-portrait.”

—USA Today

—People

“An absorbing tale of artistry, decadence, and redemption.”

—Los Angeles Times

“One of the very best rock autobiographies ever.”

— Houston Chronicle

“A glorious rock history.”

—New York Post

“This book does what many rock historians couldn’t: It debunks the legend . . . puts a lie to the glamour of what it means to be a rock star.”

—Greg Kot, Chicago Tribune

“Strong stuff. Clapton reveals its author’s journey to self-acceptance and manhood. Anyone who cares about the man and his music will want to take the trip with him.”

—Anthony DeCurtis, Rolling Stone

“Clapton is honest . . . even searing and often witty, with a hard-won survivor’s humor . . . an honorable badge of a book.”

—Stephen King, New York Times Book Review

“Riveting”

—Boston Herald

“An even, unblinking sensibility defines the author’s voice.”

—New York Times

“An unsparing self-portrait.”

—USA Today

![The History of the Highland Clearances. [2d Ed., Altered and Rev.] with a New Introd. by Ian MacPherson](https://i3.books-express.ro/bt/9780649604685/the-history-of-the-highland-clearances-2d-ed-altered-and-rev-with-a-new-introd-by-ian-macpherson.jpg)