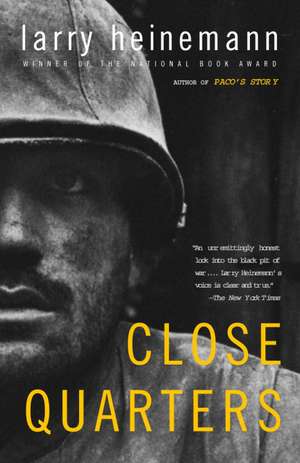

Close Quarters: Vintage Contemporaries

Autor Larry Heinemannen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2005

In the stripped-down, unsullied patois of an ordinary soldier, draftee Philip Dosier tells the story of his war. Straight from high school, too young to vote or buy himself a drink, he enters a world of mud and heat, blood and body counts, ambushes and firefights. It is here that he embarks on the brutal downward path to wisdom that awaits every soldier. In the tradition of Naked and the Dead and The Thin Red Line, Close Quarters is the harrowing story of how a decent kid from Chicago endures an extraordinary trial-- and returns profoundly altered to a world on the threshold of change.

Din seria Vintage Contemporaries

-

Preț: 109.95 lei

Preț: 109.95 lei -

Preț: 101.80 lei

Preț: 101.80 lei -

Preț: 96.52 lei

Preț: 96.52 lei -

Preț: 107.46 lei

Preț: 107.46 lei -

Preț: 91.77 lei

Preț: 91.77 lei -

Preț: 100.35 lei

Preț: 100.35 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 96.11 lei

Preț: 96.11 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 97.34 lei

Preț: 97.34 lei -

Preț: 111.92 lei

Preț: 111.92 lei -

Preț: 117.87 lei

Preț: 117.87 lei -

Preț: 95.92 lei

Preț: 95.92 lei -

Preț: 113.56 lei

Preț: 113.56 lei -

Preț: 101.88 lei

Preț: 101.88 lei -

Preț: 108.09 lei

Preț: 108.09 lei -

Preț: 115.42 lei

Preț: 115.42 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 119.87 lei

Preț: 119.87 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 87.84 lei

Preț: 87.84 lei -

Preț: 99.51 lei

Preț: 99.51 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 99.30 lei

Preț: 99.30 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 103.74 lei

Preț: 103.74 lei -

Preț: 100.98 lei

Preț: 100.98 lei -

Preț: 100.76 lei

Preț: 100.76 lei -

Preț: 89.19 lei

Preț: 89.19 lei -

Preț: 115.94 lei

Preț: 115.94 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 125.13 lei

Preț: 125.13 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 132.88 lei

Preț: 132.88 lei -

Preț: 139.63 lei

Preț: 139.63 lei -

Preț: 93.85 lei

Preț: 93.85 lei -

Preț: 106.45 lei

Preț: 106.45 lei -

Preț: 89.91 lei

Preț: 89.91 lei -

Preț: 107.92 lei

Preț: 107.92 lei -

Preț: 77.02 lei

Preț: 77.02 lei -

Preț: 125.21 lei

Preț: 125.21 lei -

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 99.75 lei -

Preț: 112.11 lei

Preț: 112.11 lei -

Preț: 83.94 lei

Preț: 83.94 lei -

Preț: 97.15 lei

Preț: 97.15 lei -

Preț: 105.82 lei

Preț: 105.82 lei -

Preț: 87.13 lei

Preț: 87.13 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 129.78 lei

Preț: 129.78 lei -

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 94.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.07€ • 19.33$ • 15.07£

18.07€ • 19.33$ • 15.07£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400076840

ISBN-10: 1400076846

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 160 x 209 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

ISBN-10: 1400076846

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 160 x 209 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

Notă biografică

Larry Heinemann’s novel Paco’s Story won the National Book Award in 1987. He lives in Chicago, Illinois.

Extras

UGLY

DEADLY

MUSIC

I stood stiffly with my feet well apart, parade-rest fashion, at the break in the barbed-wire fence between the officers' country tents and the battalion motor pool. My feet and legs itched with sweat. My shirt clung to my back. My shaving cuts burned. I watched, astonished, as the battalion Reconnaissance Platoon, thirty-some men and ten boxy squat-looking armored personnel carriers--tracks, we called them--cranked in from two months in the field, trailing a rank stink and stirring a cloud of dust that left a tingle in the air. One man slowly dismounted from each track and led it up the sloped path from the perimeter road, ground-guiding it, walking with a stumbling hangdog gait. Each man wore a sleeveless flak jacket hung with grenades, and baggy jungle trousers, the ones with large thigh pockets and drawstrings at the cuffs. The tracks followed behind like stupid, obedient draft horses, creaking and clacking along, and scraping over rocks hidden in the dust. There were sharp squeaks and irritating scratching noises, slow slack grindings, and the throttled rap of straight-pipe mufflers, all at once. And the talk, what there was, came shouted and snappy--easy obscenities and shit laughs. It was an ugly deadly music, the jerky bitter echoes of machines out of sync. A shudder went through me, as if someone were scratching his nails on a blackboard.

The men walking and the men mounted passed not fifteen feet in front of me. A moult, a smudge of dirt, and a sweat and grit and grease stink covered everything and everyone--the smell of a junkyard in a driving rainstorm. Each man looked over, looked down at me with the blandest, blankest sort of glance--almost painful to watch--neither welcome nor distance. This one or that one did signify with a slow nod of the head or an arch of the brows or a close-mouthed sigh, and I nodded or smiled back, but most glanced over dreamily and blinked a puff-eyed blink and glanced forward again.

The tracks, flat-decked affairs with sharply slanted fronts and armor-shielded machine guns (one fifty-caliber and two smaller M-60s), were painted o.d.--olive drab, a dark tallow shade of green--with large dun-colored numerals, faint and scratched but plain. The smooth straight sides and some of the curved gun shields bore thin bright gouges from Chicom claymore hits and deflected small arms. The confusion of scratches and scrapes was as wonderful and brutal as fingernails dragged across the nap of velvet. Some of the tracks had nicknames: "Lucky Louie" and "Stone Pony" and "White Hunter" and "One Bad Cat" and "The Kiss-off" and "Scratch ||||\ ||||\ |" Body count.

That summer the number would become fifteen and later twenty-six, and later still we would lose count and give up the counting, saying among ourselves, "Who fucken cares?"

The last track, the seven-seven, pulled into the motor pool, towing the very last, the seven-six. The seven-seven left the seven-six near the mechanics' quonset and pulled up and parked with the rest. A pathetic, odd moment of stillness settled over us as it finally shut down. Thick waves of engine heat rose through all the chicken-wire grillwork. The ground guides stood in front of the tracks, motionless and stoop-shouldered in ankle-deep ocher silt. The men still mounted, the drivers and gunners and TCs--track commanders--gazed at their hands or wiped dusted faces with dusted arms or stared down the broad slope at the rubbertree woodline across from the perimeter wire, squinting darkened, puffy eyes.

With the tracks facing me on line I saw that all the machine guns--ten fifty-calibers and twenty M-60s--were still loaded and pointing down. It was the frankest kind of gesture. Down where the terror would be, pointing always at the closest trees, the likeliest part of a hedgerow, the nearest rice-paddy dikes, which everyone called berms. The driver of the downed track, wearing a football-helmet-looking thing, a CVC, roused himself. He pulled himself out of his hatch and stood on the seat, sloughing off his dark glasses and bulky flak jacket and CVC, leaving them where they fell. He wore a pistol holster clipped to his trouser belt and two leather cartridge belts buckled round his waist, studded with rounds. A thick dust, almost crusted, covered his short curly hair, the razor rash on his face and neck, and the sparse hair of his arms. A glistening sweat smeared the sides of his chest and back where his flak jacket had clung to his body in folds, and his eyes shone a glassy pink against his gritty black face. The sweat soaked through in patches and dripped in runnels from his chin and fingertips and belly. He worked his jaw and cheeks, hawking up phlegm, then spit a gob of white foamy spit to leeward at the woodline down the way. It disappeared into the dust. He heaved his chest, catching his breath, all the while working his hands open and closed until he reached his fists to his eyes, leaning his head back.

"Geeee-ahhh damn!" he bellowed. Everyone in the motor pool jerked their heads, then looked away or turned their backs completely, but still listened. The man swooped down, landing in a dry puff of dust, but caught himself from falling over with his fists. He turned quickly and drew a long-handled spade out of its strap among the other pioneer tools--shovels and tanker bars and other long-handled junk. He brought the spade back over his head and began beating on the front of the track with the blade end, like it was an ax.

"You goddamned half-stepping fuck-up track!" He said it low and slow and mean. "I'm gonna tear you apart with my bare fucken hands. I'm gonna pour mo-gas on your asshole and burn you down to fucken nickels, you short-time pissant mo-gas-guzzling motherfucker!" The blade end of the handle cracked and flew off on the upswing but he kept beating on the headlight mounts and the engine-hood catch and so forth, shouting and cursing, the sweat flying from his forehead in an arc and his back rippling under the dirt. Then suddenly he stood mute, his arms hanging limp, his gaze fixed upon his boots and the dirt and the cracked and splintered tip of the spade handle. He let it slide from his fingers, then climbed the tread next to his hatch. He reached in for his shirt and steel pot and walked stiff-legged toward the mess hall and did not look back. I did not see him until later that night when he was drunk and incoherent, lying on his cot smoking dope and blowing large billowing smoke rings. The next morning he packed his duffel, sold his pistol and cartridge belts, said his goodbyes around, and went home.

The rest of the platoon, singly and by twos and threes, slowly went to work dismounting the guns for cleaning, and after a moment only one man was visible. He leaned against the sloped front of his track, stripped to the waist with a stub of cigar between his teeth. His trousers, soaked through around the belt, were covered with dirt and grease, stiff and puckered at the knees. He wore a faded web belt low on his hips; a knife on the right, a green plastic canteen on his left, and a forty-five-caliber automatic pistol in a black holster hung in front of his crotch. He told me later he wore the pistol for protection the way some people kept something thick in their breast pocket, "like a Bible or a fuck book, ya know?" He walked toward me with a slow ambling gait, smiled to himself as he passed, and went over to a fifty-five-gallon drum sunk in the ground, the Enlisted Men's Club piss tube. His hair shone with sweat, was matted and wild-looking. He had brown teeth and dark wrinkles around his mouth, gray watery eyes, and tiny inflamed scars across his stomach, like the deep and sweeping scratches of cats. His whole face seemed pulled together around the eyes, as though someone had squeezed it. He stood with his feet well apart, looking straight down at the stream of piss. There was a rich humus smell about him, not plain dirt or soft crumbling chunks, but powdery and damp, a thing that clings to everything it touches.

"Excuse me," I said. "Could you tell me where I can find the platoon leader?"

"Say? The El-tee?" His words came easy and weary and dry. "See that track on the end there?" He pumped his thumb over his shoulder without looking up. "He's aroun' back some fucken place. Ya can't miss him. He's the dude with the silver spoon in his mouth. You new, huh? M' name's Cross."

"l'm Philip Dosier. Well, I'll see you later."

"I don't doubt."

I walked around the side of the six-niner, making sure all my buttons were buttoned, pulling the slack out of my rifle sling, and adjusting my steel pot down over my eyes, garrison style, then walked around to the back. All the activity was there, all the way down the line. The ramp of each track was open, some swung all the way to the ground, some held level to the floors inside with water cans or wooden boxes. Everyone was stripped to the waist and bareheaded, going about his work with slow languid motions because of the heat; shaking out blankets and poncho liners in a cloud of dust and chaff and lint, or cleaning the stripped-down machine guns in cans of gasoline, or policing up brass cartridges by the armfuls and tossing the cartridges, cans, and all into fifty-five-gallon drums set out for junk. The gas truck, a deuce-and-a-half with two fuel tanks on the back marked "Mo-gas," had begun moving up the line, refueling. I thought gas-powered tracks were obsolete. I had never seen any before, except the two on display at the Patton Museum at Fort Knox.

Lieutenant Greer sat in the shade inside the back of his track on one of the low metal benches, folding a map. He was a husky, meaty-looking dude with short, shaggy, filthy hair and freckles and red wrinkle marks from his CVC across the forehead and under the ears. He wore back-in-the-world fatigues covered with dust; a brass armor insignia on one collar, his silver lieutenant's bar on the other, and a pair of amber-tinted driving goggles around his neck.

The first time I came down with heat exhaustion a couple months later, May or June it might have been, Lieutenant Greer called the dust-off chopper himself. He laid me out on the litter and held me up, leaning me against his thigh, and poured canteen after canteen of tepid water over my head. He held his canteen cup while I washed down half a handful of salt tablets, spilling mouthfuls of water down my chin and chest. I vomited twice, finally dry-heaving on my hands and knees while he soaked compresses on the back of my neck with more water. When the chopper came, the Colonel's command chopper because the dust-offs were busy with Bravo and Charlie companies, the Lieutenant walked me over to it and gave me a hand up, saying thanks to the Colonel. I sat among the racks of the Colonel's radios until he landed me at the battalion aid station, and late that afternoon the Lieutenant came over to fetch me back to the platoon. Toward the end of summer when Greer went home we threw a party for him at the platoon tents, everybody getting ripped and red-eyed drinking quarts, drinking his health. He shook everybody's hand and wished us good luck and left, staggering out into the moonlight, and I never saw him again.

The inside of his track was very neat, much neater than any of the rest. There was a collapsed litter strapped close under the armor deck, three radios, ammunition cans neatly stacked on the floor under the TC hatch, waterproof duffel bags full of clothes along one wall, and boxes of fragmentation grenades and claymores, command-detonated antipersonnel mines about the size of the top of a shoe box and curved outward. The Lieutenant's M-1 carbine and a sandbag filled with magazines hung on a hook behind his head.

I saluted and nervously introduced myself. After a moment of silly questions and silly answers and that same stupid lecture about bringing him my personal problems, the Lieutenant called on the radio for Seven-zero, Staff Sergeant Surtees, the Platoon Sergeant.

Surtees was a heavyset Negro who wore the only shoulder-holster forty-five in the platoon and the only man, other than the Lieutenant, wearing a shirt, the sleeves rolled in precise folds with all his insignia and rank patches: E-6 chevrons and 25th Division patch and name patch.

He smoked big cheap cigars which he rolled in his fingers as he talked to the platoon in formation, and would pause to spit tobacco for emphasis, but he could never get the hang of it and so always had spittle dribbled on his shirts. He loved to say, "E'ery swingin' dick," and here he would take pause to spit on his shirt, "in this platoon is chicken shit," and then would bug his eyes, trying to flash fire. When he had an announcement for the whole platoon, that the mail was in or chow was ready or the water trailer had arrived he would call us on the radio and say, "Rom-e-o, Romeo. This is Seven--ze-ro!" and then say whatever it was he wanted to say.

In the fall when his 1049 came, his transfer to Division, it took him fifteen minutes to gather his gear and sign out of the company. Word came down to the tents that Surtees was shipping out and a bunch of old-timers went down to see him go. When he slid into the jeep for the ride up to the airport, Quinn, a dude who transferred into the platoon that summer, walked up beside him, dropped a small package in his lap, and said, "It's a special belt, see? Ya take yer dick an' strap it to yer leg, get it stretched out good an' long, say 'bout fifteen or twenty feet. Then some night when yer good and fucked up on that NCO Club booze, just real down home fucked up and horny, why just whip it out, rub it up, an' shove it up yer fat nigger ass." Then everybody laughed, even the driver, who hardly knew him.

Sergeant Surtees stood in front of the Lieutenant at mock attention and gave me the "Teamwork, fight like hell, and sleep on your own time" speech that he would give every new replacement. "Falling asleep on guard duty is a court-martial offense; incorrect radio procedure will not be tolerated, the FCC monitors all frequencies; and you will at all times address me as Platoon Sergeant Surtees. Is that clear, Pfc?"

DEADLY

MUSIC

I stood stiffly with my feet well apart, parade-rest fashion, at the break in the barbed-wire fence between the officers' country tents and the battalion motor pool. My feet and legs itched with sweat. My shirt clung to my back. My shaving cuts burned. I watched, astonished, as the battalion Reconnaissance Platoon, thirty-some men and ten boxy squat-looking armored personnel carriers--tracks, we called them--cranked in from two months in the field, trailing a rank stink and stirring a cloud of dust that left a tingle in the air. One man slowly dismounted from each track and led it up the sloped path from the perimeter road, ground-guiding it, walking with a stumbling hangdog gait. Each man wore a sleeveless flak jacket hung with grenades, and baggy jungle trousers, the ones with large thigh pockets and drawstrings at the cuffs. The tracks followed behind like stupid, obedient draft horses, creaking and clacking along, and scraping over rocks hidden in the dust. There were sharp squeaks and irritating scratching noises, slow slack grindings, and the throttled rap of straight-pipe mufflers, all at once. And the talk, what there was, came shouted and snappy--easy obscenities and shit laughs. It was an ugly deadly music, the jerky bitter echoes of machines out of sync. A shudder went through me, as if someone were scratching his nails on a blackboard.

The men walking and the men mounted passed not fifteen feet in front of me. A moult, a smudge of dirt, and a sweat and grit and grease stink covered everything and everyone--the smell of a junkyard in a driving rainstorm. Each man looked over, looked down at me with the blandest, blankest sort of glance--almost painful to watch--neither welcome nor distance. This one or that one did signify with a slow nod of the head or an arch of the brows or a close-mouthed sigh, and I nodded or smiled back, but most glanced over dreamily and blinked a puff-eyed blink and glanced forward again.

The tracks, flat-decked affairs with sharply slanted fronts and armor-shielded machine guns (one fifty-caliber and two smaller M-60s), were painted o.d.--olive drab, a dark tallow shade of green--with large dun-colored numerals, faint and scratched but plain. The smooth straight sides and some of the curved gun shields bore thin bright gouges from Chicom claymore hits and deflected small arms. The confusion of scratches and scrapes was as wonderful and brutal as fingernails dragged across the nap of velvet. Some of the tracks had nicknames: "Lucky Louie" and "Stone Pony" and "White Hunter" and "One Bad Cat" and "The Kiss-off" and "Scratch ||||\ ||||\ |" Body count.

That summer the number would become fifteen and later twenty-six, and later still we would lose count and give up the counting, saying among ourselves, "Who fucken cares?"

The last track, the seven-seven, pulled into the motor pool, towing the very last, the seven-six. The seven-seven left the seven-six near the mechanics' quonset and pulled up and parked with the rest. A pathetic, odd moment of stillness settled over us as it finally shut down. Thick waves of engine heat rose through all the chicken-wire grillwork. The ground guides stood in front of the tracks, motionless and stoop-shouldered in ankle-deep ocher silt. The men still mounted, the drivers and gunners and TCs--track commanders--gazed at their hands or wiped dusted faces with dusted arms or stared down the broad slope at the rubbertree woodline across from the perimeter wire, squinting darkened, puffy eyes.

With the tracks facing me on line I saw that all the machine guns--ten fifty-calibers and twenty M-60s--were still loaded and pointing down. It was the frankest kind of gesture. Down where the terror would be, pointing always at the closest trees, the likeliest part of a hedgerow, the nearest rice-paddy dikes, which everyone called berms. The driver of the downed track, wearing a football-helmet-looking thing, a CVC, roused himself. He pulled himself out of his hatch and stood on the seat, sloughing off his dark glasses and bulky flak jacket and CVC, leaving them where they fell. He wore a pistol holster clipped to his trouser belt and two leather cartridge belts buckled round his waist, studded with rounds. A thick dust, almost crusted, covered his short curly hair, the razor rash on his face and neck, and the sparse hair of his arms. A glistening sweat smeared the sides of his chest and back where his flak jacket had clung to his body in folds, and his eyes shone a glassy pink against his gritty black face. The sweat soaked through in patches and dripped in runnels from his chin and fingertips and belly. He worked his jaw and cheeks, hawking up phlegm, then spit a gob of white foamy spit to leeward at the woodline down the way. It disappeared into the dust. He heaved his chest, catching his breath, all the while working his hands open and closed until he reached his fists to his eyes, leaning his head back.

"Geeee-ahhh damn!" he bellowed. Everyone in the motor pool jerked their heads, then looked away or turned their backs completely, but still listened. The man swooped down, landing in a dry puff of dust, but caught himself from falling over with his fists. He turned quickly and drew a long-handled spade out of its strap among the other pioneer tools--shovels and tanker bars and other long-handled junk. He brought the spade back over his head and began beating on the front of the track with the blade end, like it was an ax.

"You goddamned half-stepping fuck-up track!" He said it low and slow and mean. "I'm gonna tear you apart with my bare fucken hands. I'm gonna pour mo-gas on your asshole and burn you down to fucken nickels, you short-time pissant mo-gas-guzzling motherfucker!" The blade end of the handle cracked and flew off on the upswing but he kept beating on the headlight mounts and the engine-hood catch and so forth, shouting and cursing, the sweat flying from his forehead in an arc and his back rippling under the dirt. Then suddenly he stood mute, his arms hanging limp, his gaze fixed upon his boots and the dirt and the cracked and splintered tip of the spade handle. He let it slide from his fingers, then climbed the tread next to his hatch. He reached in for his shirt and steel pot and walked stiff-legged toward the mess hall and did not look back. I did not see him until later that night when he was drunk and incoherent, lying on his cot smoking dope and blowing large billowing smoke rings. The next morning he packed his duffel, sold his pistol and cartridge belts, said his goodbyes around, and went home.

The rest of the platoon, singly and by twos and threes, slowly went to work dismounting the guns for cleaning, and after a moment only one man was visible. He leaned against the sloped front of his track, stripped to the waist with a stub of cigar between his teeth. His trousers, soaked through around the belt, were covered with dirt and grease, stiff and puckered at the knees. He wore a faded web belt low on his hips; a knife on the right, a green plastic canteen on his left, and a forty-five-caliber automatic pistol in a black holster hung in front of his crotch. He told me later he wore the pistol for protection the way some people kept something thick in their breast pocket, "like a Bible or a fuck book, ya know?" He walked toward me with a slow ambling gait, smiled to himself as he passed, and went over to a fifty-five-gallon drum sunk in the ground, the Enlisted Men's Club piss tube. His hair shone with sweat, was matted and wild-looking. He had brown teeth and dark wrinkles around his mouth, gray watery eyes, and tiny inflamed scars across his stomach, like the deep and sweeping scratches of cats. His whole face seemed pulled together around the eyes, as though someone had squeezed it. He stood with his feet well apart, looking straight down at the stream of piss. There was a rich humus smell about him, not plain dirt or soft crumbling chunks, but powdery and damp, a thing that clings to everything it touches.

"Excuse me," I said. "Could you tell me where I can find the platoon leader?"

"Say? The El-tee?" His words came easy and weary and dry. "See that track on the end there?" He pumped his thumb over his shoulder without looking up. "He's aroun' back some fucken place. Ya can't miss him. He's the dude with the silver spoon in his mouth. You new, huh? M' name's Cross."

"l'm Philip Dosier. Well, I'll see you later."

"I don't doubt."

I walked around the side of the six-niner, making sure all my buttons were buttoned, pulling the slack out of my rifle sling, and adjusting my steel pot down over my eyes, garrison style, then walked around to the back. All the activity was there, all the way down the line. The ramp of each track was open, some swung all the way to the ground, some held level to the floors inside with water cans or wooden boxes. Everyone was stripped to the waist and bareheaded, going about his work with slow languid motions because of the heat; shaking out blankets and poncho liners in a cloud of dust and chaff and lint, or cleaning the stripped-down machine guns in cans of gasoline, or policing up brass cartridges by the armfuls and tossing the cartridges, cans, and all into fifty-five-gallon drums set out for junk. The gas truck, a deuce-and-a-half with two fuel tanks on the back marked "Mo-gas," had begun moving up the line, refueling. I thought gas-powered tracks were obsolete. I had never seen any before, except the two on display at the Patton Museum at Fort Knox.

Lieutenant Greer sat in the shade inside the back of his track on one of the low metal benches, folding a map. He was a husky, meaty-looking dude with short, shaggy, filthy hair and freckles and red wrinkle marks from his CVC across the forehead and under the ears. He wore back-in-the-world fatigues covered with dust; a brass armor insignia on one collar, his silver lieutenant's bar on the other, and a pair of amber-tinted driving goggles around his neck.

The first time I came down with heat exhaustion a couple months later, May or June it might have been, Lieutenant Greer called the dust-off chopper himself. He laid me out on the litter and held me up, leaning me against his thigh, and poured canteen after canteen of tepid water over my head. He held his canteen cup while I washed down half a handful of salt tablets, spilling mouthfuls of water down my chin and chest. I vomited twice, finally dry-heaving on my hands and knees while he soaked compresses on the back of my neck with more water. When the chopper came, the Colonel's command chopper because the dust-offs were busy with Bravo and Charlie companies, the Lieutenant walked me over to it and gave me a hand up, saying thanks to the Colonel. I sat among the racks of the Colonel's radios until he landed me at the battalion aid station, and late that afternoon the Lieutenant came over to fetch me back to the platoon. Toward the end of summer when Greer went home we threw a party for him at the platoon tents, everybody getting ripped and red-eyed drinking quarts, drinking his health. He shook everybody's hand and wished us good luck and left, staggering out into the moonlight, and I never saw him again.

The inside of his track was very neat, much neater than any of the rest. There was a collapsed litter strapped close under the armor deck, three radios, ammunition cans neatly stacked on the floor under the TC hatch, waterproof duffel bags full of clothes along one wall, and boxes of fragmentation grenades and claymores, command-detonated antipersonnel mines about the size of the top of a shoe box and curved outward. The Lieutenant's M-1 carbine and a sandbag filled with magazines hung on a hook behind his head.

I saluted and nervously introduced myself. After a moment of silly questions and silly answers and that same stupid lecture about bringing him my personal problems, the Lieutenant called on the radio for Seven-zero, Staff Sergeant Surtees, the Platoon Sergeant.

Surtees was a heavyset Negro who wore the only shoulder-holster forty-five in the platoon and the only man, other than the Lieutenant, wearing a shirt, the sleeves rolled in precise folds with all his insignia and rank patches: E-6 chevrons and 25th Division patch and name patch.

He smoked big cheap cigars which he rolled in his fingers as he talked to the platoon in formation, and would pause to spit tobacco for emphasis, but he could never get the hang of it and so always had spittle dribbled on his shirts. He loved to say, "E'ery swingin' dick," and here he would take pause to spit on his shirt, "in this platoon is chicken shit," and then would bug his eyes, trying to flash fire. When he had an announcement for the whole platoon, that the mail was in or chow was ready or the water trailer had arrived he would call us on the radio and say, "Rom-e-o, Romeo. This is Seven--ze-ro!" and then say whatever it was he wanted to say.

In the fall when his 1049 came, his transfer to Division, it took him fifteen minutes to gather his gear and sign out of the company. Word came down to the tents that Surtees was shipping out and a bunch of old-timers went down to see him go. When he slid into the jeep for the ride up to the airport, Quinn, a dude who transferred into the platoon that summer, walked up beside him, dropped a small package in his lap, and said, "It's a special belt, see? Ya take yer dick an' strap it to yer leg, get it stretched out good an' long, say 'bout fifteen or twenty feet. Then some night when yer good and fucked up on that NCO Club booze, just real down home fucked up and horny, why just whip it out, rub it up, an' shove it up yer fat nigger ass." Then everybody laughed, even the driver, who hardly knew him.

Sergeant Surtees stood in front of the Lieutenant at mock attention and gave me the "Teamwork, fight like hell, and sleep on your own time" speech that he would give every new replacement. "Falling asleep on guard duty is a court-martial offense; incorrect radio procedure will not be tolerated, the FCC monitors all frequencies; and you will at all times address me as Platoon Sergeant Surtees. Is that clear, Pfc?"

Recenzii

"An unremittingly honest look into the black pit of war....Larry Heinemann's voice is clear and true." -The New York Time

"The best work of fiction to come out of the Vietnam War." -The Houston Chronicle

"Close Quarters can stand with the finest Vietnam writing, fact or fiction." --Chicago Tribune

“The most ambitious and substantial novel about the war in Vietnam . . . . the first one that people can read 75 years from now and gain an insight into how the war was truly fought . . . following the talk of the soldiers, you feel more like an eavesdropper than a reader.” —Kansas City Star

"The best work of fiction to come out of the Vietnam War." -The Houston Chronicle

"Close Quarters can stand with the finest Vietnam writing, fact or fiction." --Chicago Tribune

“The most ambitious and substantial novel about the war in Vietnam . . . . the first one that people can read 75 years from now and gain an insight into how the war was truly fought . . . following the talk of the soldiers, you feel more like an eavesdropper than a reader.” —Kansas City Star