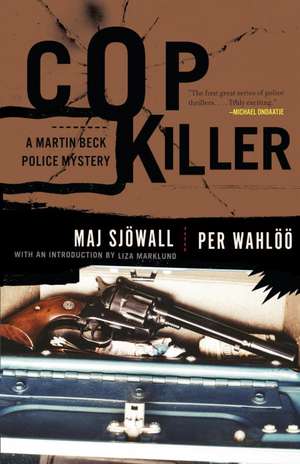

Cop Killer: A Martin Beck Mystery

Autor Maj Sjowall, Per Wahloo Traducere de Thomas Tealen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2010

In a country town, a woman is brutally murdered and left buried in a swamp. There are two main suspects: her closest neighbor and her ex-husband. Meanwhile, on a quiet suburban street a midnight shootout takes place between three cops and two teenage boys. Dead, one cop and one kid. Wounded, two cops. Escaped, one kid. Martin Beck and his partner Lenart Kollberg are called in to investigate. As Beck digs deeper into the murky waters of the young girl’s murder, Kollberg scours the town for the teenager, and together they are forced to examine the changing face of crime.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 63.96 lei 3-5 săpt. | +10.69 lei 4-10 zile |

| HarperCollins Publishers – 5 ian 2012 | 63.96 lei 3-5 săpt. | +10.69 lei 4-10 zile |

| Vintage Books USA – 30 iun 2010 | 107.27 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 107.27 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.53€ • 21.35$ • 16.95£

20.53€ • 21.35$ • 16.95£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307390899

ISBN-10: 0307390896

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 134 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307390896

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 134 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, her husband and coauthor, wrote ten Martin Beck mysteries. Mr Wahlöö, who died in 1975, was a reporter for several Swedish newspapers and magazines and wrote numerous radio and television plays, film scripts, short stories, and novels. Maj Sjöwall is also a poet.

Extras

Chapter 1

She reached the bus stop well ahead of the bus, which would not be along for half an hour yet. Thirty minutes of a person's life is not an especially long time. Besides, she was used to waiting and was always early. She thought about what she would make for dinner, and a little about what she looked like—her usual idle thoughts.

By the time the bus came, she would no longer have any thoughts at all. She had only twenty-seven minutes left to live.

It was a pretty day, clear and gusty, with a touch of early autumn chill in the wind, but her hair was too well processed to be affected by the weather.

What did she look like?

Standing there by the side of the road this way, she might have been in her forties, a rather tall, sturdy woman with straight legs and broad hips and a little secret fat that she was very much afraid might show. She dressed mostly according to fashion, often at the expense of comfort, and on this blustery fall day she was wearing a bright green 1930s coat, nylon stockings, and thin brown patent leather boots with platform soles. She was carrying a small square handbag with a large brass clasp slung over her left shoulder. This too was brown, as were her suede gloves. Her blond hair had been well sprayed, and she was carefully made up.

She didn't notice him until he stopped. He leaned over and threw open the passenger door.

"Want a lift?" he said.

"Yes," she said, a little flurried. "Sure. I didn't think . . ."

"What didn't you think?"

"Well, I didn't expect to get a ride. I was going to take the bus."

"I knew you'd be here," he said. "And it's not out of my way, as it happens. Jump in, now, look alive."

Look alive. How many seconds did it take her to climb in and sit down beside the driver? Look alive. He drove fast, and they were quickly out of town.

She was sitting with her handbag in her lap, slightly tense, flustered perhaps, or at least somewhat surprised. Whether happily or unhappily it was impossible to say. She didn't know herself.

She looked at him from the side, but the man's attention seemed wholly concentrated on the driving.

He swung off the main road to the right, but then turned again almost immediately. The same procedure was repeated, and the road grew steadily worse. It was questionable whether it could be called a road any more or not.

"What are you going to do?" she said, with a frightened little giggle.

"You'll find out."

"Where?"

"Here," he said and braked to a stop.

Ahead of him he could see his own wheeltracks in the moss. They were not many hours old.

"Over there," he said with a nod. "Behind the woodpile. That's a good place."

"Are you kidding?"

"I never kid about things like that."

He seemed hurt or upset by the question.

"But my coat," she said.

"Leave it here."

"But . . ."

"There's a blanket."

He climbed out, walked around, and held the door for her.

She accepted his help and took off the coat. Folded it neatly and placed it on the seat beside her handbag.

"There."

He seemed calm and collected, but he didn't take her hand as he walked slowly toward the woodpile. She followed along behind.

It was warm and sunny behind the woodpile and sheltered from the wind. The air was filled with the buzzing of flies and the fresh smell of greenery. It was still almost summer, and this summer had been the warmest in the weather bureau's history.

It wasn't actually an ordinary woodpile but rather a stack of beech logs, cut in sections and piled about six feet high.

"Take off your blouse."

"Yes," she said shyly.

He waited patiently while she undid the buttons.

Then he helped her off with the blouse, gingerly, without touching her body.

She was left standing with the garment in one hand, not knowing what to do with it.

He took it from her and placed it carefully over the edge of the pile of logs. An earwig zigzagged across the fabric.

She stood before him in her skirt, her breasts heavy in the skin-colored bra, her eyes on the ground, her back against the even surface of sawed timber.

The moment had come to act, and he did so with such speed and suddenness that she never had time to grasp what was happening. Her reactions had never been especially quick.

He grabbed the waistband at her navel with both hands and ripped open her skirt and her pantyhose in a single violent motion. He was strong, and the fabric gave instantly, with a rasping snarl like the sound of old canvas being torn. The skirt fell to her calves, and he jerked her pantyhose and panties down to her knees, then pulled up the left cup of her bra so that her breast flopped down, loose and heavy.

Only then did she raise her head and look into his eyes. Eyes that were filled with disgust, loathing, and savage delight.

The idea of screaming never had time to take shape in her mind. For that matter, it would have been pointless. The place had been chosen with care.

He raised his arms straight out and up, closed his powerful suntanned fingers around her throat, and strangled her.

The back of her head was pressed against the pile of logs, and she thought: My hair.

That was her last thought.

He held his grip on her throat a little longer than necessary.

Then he let go with his right hand and, holding her body upright with his left, he struck her as hard as he could in the groin with his right fist.

She fell to the ground and lay among the musk madder and last year's leaves. She was essentially naked.

A rattling sound came from her throat. He knew this was normal and that she was already dead.

Death is never very pretty. In addition, she had never been pretty during her lifetime, not even when she was young.

Lying there in the forest undergrowth, she was, at best, pathetic.

He waited a minute or so until his breathing had returned to normal and his heart had stopped racing.

And then he was himself again, calm and rational.

Beyond the pile of logs was a dense windfall from the big autumn storm of 1968, and beyond that, a dense planting of spruce trees about the height of a man.

He lifted her under the arms and was disgusted by the feel of the sticky, damp stubble in her armpits against the palms of his hands.

It took some time to drag her through the almost impassable terrain of sprawling tree trunks and uptorn roots, but he saw no need to hurry. Several yards into the spruce thicket there was a marshy depression filled with muddy yellow water. He shoved her into it and tramped her limp body down into the ooze. But first he looked at her for a moment. She was still tanned from the sunny summer, but the skin on her left breast was pale and flecked with light-brown spots. As pale as death, one might say.

He walked back to get the green coat and wondered for a moment what he should do with her handbag. Then he took the blouse from the timber pile, wrapped it around the purse, and carried everything back to the muddy pool. The color of the coat was rather striking, so he fetched a suitable stick and pushed the coat, the blouse, and the handbag as deep as he could down into the mud.

He spent the next quarter of an hour collecting spruce branches and chunks of moss. He covered the pool so thoroughly that no casual passerby would ever notice the mud hole existed.

He studied the result for a few minutes and made several corrections before he was satisfied.

Then he shrugged his shoulders and went back to where he was parked. He took a clean cotton rag from the floor and cleaned off his rubber boots. When he was done, he threw the rag on the ground. It lay there wet and muddy and clearly visible, but it didn't matter. A cotton rag can be anywhere. It proves nothing and can't be linked to anything in particular.

Then he turned the car around and drove away. As he drove, it occurred to him that everything had gone well, and that she had got precisely what she deserved.

She reached the bus stop well ahead of the bus, which would not be along for half an hour yet. Thirty minutes of a person's life is not an especially long time. Besides, she was used to waiting and was always early. She thought about what she would make for dinner, and a little about what she looked like—her usual idle thoughts.

By the time the bus came, she would no longer have any thoughts at all. She had only twenty-seven minutes left to live.

It was a pretty day, clear and gusty, with a touch of early autumn chill in the wind, but her hair was too well processed to be affected by the weather.

What did she look like?

Standing there by the side of the road this way, she might have been in her forties, a rather tall, sturdy woman with straight legs and broad hips and a little secret fat that she was very much afraid might show. She dressed mostly according to fashion, often at the expense of comfort, and on this blustery fall day she was wearing a bright green 1930s coat, nylon stockings, and thin brown patent leather boots with platform soles. She was carrying a small square handbag with a large brass clasp slung over her left shoulder. This too was brown, as were her suede gloves. Her blond hair had been well sprayed, and she was carefully made up.

She didn't notice him until he stopped. He leaned over and threw open the passenger door.

"Want a lift?" he said.

"Yes," she said, a little flurried. "Sure. I didn't think . . ."

"What didn't you think?"

"Well, I didn't expect to get a ride. I was going to take the bus."

"I knew you'd be here," he said. "And it's not out of my way, as it happens. Jump in, now, look alive."

Look alive. How many seconds did it take her to climb in and sit down beside the driver? Look alive. He drove fast, and they were quickly out of town.

She was sitting with her handbag in her lap, slightly tense, flustered perhaps, or at least somewhat surprised. Whether happily or unhappily it was impossible to say. She didn't know herself.

She looked at him from the side, but the man's attention seemed wholly concentrated on the driving.

He swung off the main road to the right, but then turned again almost immediately. The same procedure was repeated, and the road grew steadily worse. It was questionable whether it could be called a road any more or not.

"What are you going to do?" she said, with a frightened little giggle.

"You'll find out."

"Where?"

"Here," he said and braked to a stop.

Ahead of him he could see his own wheeltracks in the moss. They were not many hours old.

"Over there," he said with a nod. "Behind the woodpile. That's a good place."

"Are you kidding?"

"I never kid about things like that."

He seemed hurt or upset by the question.

"But my coat," she said.

"Leave it here."

"But . . ."

"There's a blanket."

He climbed out, walked around, and held the door for her.

She accepted his help and took off the coat. Folded it neatly and placed it on the seat beside her handbag.

"There."

He seemed calm and collected, but he didn't take her hand as he walked slowly toward the woodpile. She followed along behind.

It was warm and sunny behind the woodpile and sheltered from the wind. The air was filled with the buzzing of flies and the fresh smell of greenery. It was still almost summer, and this summer had been the warmest in the weather bureau's history.

It wasn't actually an ordinary woodpile but rather a stack of beech logs, cut in sections and piled about six feet high.

"Take off your blouse."

"Yes," she said shyly.

He waited patiently while she undid the buttons.

Then he helped her off with the blouse, gingerly, without touching her body.

She was left standing with the garment in one hand, not knowing what to do with it.

He took it from her and placed it carefully over the edge of the pile of logs. An earwig zigzagged across the fabric.

She stood before him in her skirt, her breasts heavy in the skin-colored bra, her eyes on the ground, her back against the even surface of sawed timber.

The moment had come to act, and he did so with such speed and suddenness that she never had time to grasp what was happening. Her reactions had never been especially quick.

He grabbed the waistband at her navel with both hands and ripped open her skirt and her pantyhose in a single violent motion. He was strong, and the fabric gave instantly, with a rasping snarl like the sound of old canvas being torn. The skirt fell to her calves, and he jerked her pantyhose and panties down to her knees, then pulled up the left cup of her bra so that her breast flopped down, loose and heavy.

Only then did she raise her head and look into his eyes. Eyes that were filled with disgust, loathing, and savage delight.

The idea of screaming never had time to take shape in her mind. For that matter, it would have been pointless. The place had been chosen with care.

He raised his arms straight out and up, closed his powerful suntanned fingers around her throat, and strangled her.

The back of her head was pressed against the pile of logs, and she thought: My hair.

That was her last thought.

He held his grip on her throat a little longer than necessary.

Then he let go with his right hand and, holding her body upright with his left, he struck her as hard as he could in the groin with his right fist.

She fell to the ground and lay among the musk madder and last year's leaves. She was essentially naked.

A rattling sound came from her throat. He knew this was normal and that she was already dead.

Death is never very pretty. In addition, she had never been pretty during her lifetime, not even when she was young.

Lying there in the forest undergrowth, she was, at best, pathetic.

He waited a minute or so until his breathing had returned to normal and his heart had stopped racing.

And then he was himself again, calm and rational.

Beyond the pile of logs was a dense windfall from the big autumn storm of 1968, and beyond that, a dense planting of spruce trees about the height of a man.

He lifted her under the arms and was disgusted by the feel of the sticky, damp stubble in her armpits against the palms of his hands.

It took some time to drag her through the almost impassable terrain of sprawling tree trunks and uptorn roots, but he saw no need to hurry. Several yards into the spruce thicket there was a marshy depression filled with muddy yellow water. He shoved her into it and tramped her limp body down into the ooze. But first he looked at her for a moment. She was still tanned from the sunny summer, but the skin on her left breast was pale and flecked with light-brown spots. As pale as death, one might say.

He walked back to get the green coat and wondered for a moment what he should do with her handbag. Then he took the blouse from the timber pile, wrapped it around the purse, and carried everything back to the muddy pool. The color of the coat was rather striking, so he fetched a suitable stick and pushed the coat, the blouse, and the handbag as deep as he could down into the mud.

He spent the next quarter of an hour collecting spruce branches and chunks of moss. He covered the pool so thoroughly that no casual passerby would ever notice the mud hole existed.

He studied the result for a few minutes and made several corrections before he was satisfied.

Then he shrugged his shoulders and went back to where he was parked. He took a clean cotton rag from the floor and cleaned off his rubber boots. When he was done, he threw the rag on the ground. It lay there wet and muddy and clearly visible, but it didn't matter. A cotton rag can be anywhere. It proves nothing and can't be linked to anything in particular.

Then he turned the car around and drove away. As he drove, it occurred to him that everything had gone well, and that she had got precisely what she deserved.

Recenzii

“The first great series of police thrillers. . . . Truly exciting.”—Michael Ondaatje

"The [Martin Beck] series has maintained such a degree of excellence that comparisons are near impossible."--Minneapolis Tribune

“It’s hard to think of any other thriller writers (apart from Simenon perhaps) who can capture so much of a society in a couple of hundred pages and yet still hold true to the thriller form.”—Sean and Nicci French

“Sjöwall and Wahlöö write unsparingly and unswervingly. . . . Their plots are second to none.”—Val McDermid

“Sjöwall and Wahlöö continue to be tops for discriminating crime book readers.”—Denver Post

“Ingenious. . . . Their mysteries don’t just read well; they reread even better. . . . The writing is lean, with mournful undertones.”—The New York Times

”Martin Beck is as always very believable: this, we feel, is what it must mean to be an honest and intelligent policeman in modern Sweden, or anywhere else.”—Times Literary Supplement

“In the hands of Wahlöö and Sjöwal . . . the police story ߝ with no loss of suspense or action ߝ [has been] brilliantly fashioned into a sharp instrument for social commentary.”—Washington Post

“Edge-of-the-seat suspense.”—San Francisco Examiner

"The [Martin Beck] series has maintained such a degree of excellence that comparisons are near impossible."--Minneapolis Tribune

“It’s hard to think of any other thriller writers (apart from Simenon perhaps) who can capture so much of a society in a couple of hundred pages and yet still hold true to the thriller form.”—Sean and Nicci French

“Sjöwall and Wahlöö write unsparingly and unswervingly. . . . Their plots are second to none.”—Val McDermid

“Sjöwall and Wahlöö continue to be tops for discriminating crime book readers.”—Denver Post

“Ingenious. . . . Their mysteries don’t just read well; they reread even better. . . . The writing is lean, with mournful undertones.”—The New York Times

”Martin Beck is as always very believable: this, we feel, is what it must mean to be an honest and intelligent policeman in modern Sweden, or anywhere else.”—Times Literary Supplement

“In the hands of Wahlöö and Sjöwal . . . the police story ߝ with no loss of suspense or action ߝ [has been] brilliantly fashioned into a sharp instrument for social commentary.”—Washington Post

“Edge-of-the-seat suspense.”—San Francisco Examiner

Descriere

The shocking penultimate novel in the Martin Beck mystery series by Sjwall and Wahl finds Beck investigating parallel cases that have shocked a small community. After a woman is brutally murdered and a shootout between three cops and two teenage boys occurs, Beck and his partner Lenart Kollberg are called in on the cases.