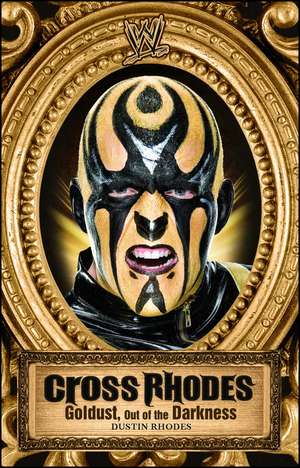

Cross Rhodes: Goldust, Out of the Darkness: WWE

Autor Dustin Rhodes Cu Mark Vancilen Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 ian 2011

As a young boy, Dustin tried to find himself while growing up in his father's shadow. Dusty wanted his son to play football, mostly to avoid the brutal business that was making him famous. But Dustin wanted nothing more than to follow his father into the world of professional wrestling.

It wasn't until the middle of a painful five-year estrangement between father and son that Dustin finally stepped out of his father's boots - literally - and made a name for himself as Goldust. But for Dustin, the dark edges of the controversial character became a matter of art imitating life, and despite an emotional reunion with his father, redemption and rehabilitation were still well down the line…

Preț: 93.15 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 140

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.83€ • 18.54$ • 14.72£

17.83€ • 18.54$ • 14.72£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781439195161

ISBN-10: 1439195161

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: b-w photos throughout

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Original.

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Seria WWE

ISBN-10: 1439195161

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: b-w photos throughout

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Original.

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Seria WWE

Notă biografică

Mark Vancil is president of Rare Air Media, a publishing and communications company based in Winnetka, Illinois, that has produced dozens of award-winning books and custom publishing programs for sports, publishing and entertainment clients.

Extras

ONE

THE FEVER

I got the fever as a young boy growing up in the long shadows of a big man in Austin, Texas.

The American Dream, Dusty Rhodes, is my dad. As a young boy, all I knew was that my dad was gone all the time. For the most part, my mother, my sister Kristin, and I were left to fend for ourselves. I can remember being five or six years old and seeing my dad come home after a long trip. I was like any other small boy. I wanted to crawl all over my dad when he finally walked through the front door. But he was too tired and his body too sore.

Back then, wrestlers worked territories, and they were gone for months at a time. He might spend two or three weeks in one place, come home, then head off to Japan for a month or more. He would take us places and we would get time with him, but it was always cut short by his schedule. My dad was naturally charismatic and very smart. I certainly didn’t understand how smart he was about his career then, but as a little boy all I wanted was more time with him. He was larger than life to me.

Then, one day, he was gone for good. My parents divorced right around the time I entered first grade at a private Christian school in Austin. I didn’t get the chance to know him the way a young boy wants to know his father. I was seven years old when my parents divorced. I remember crying for hours at a time during the days, weeks, and months that followed his departure. Even though he was gone a lot before the divorce, I always knew he’d come walking into the house in his cowboy boots and hat. Divorce meant the exact opposite. My father was gone and he wasn’t ever coming back. In those days, his life was rolling along at one hundred miles an hour, and being home with family was the slowest part of his existence.

As his stature grew in the business, the shadow became larger and more difficult for me. I don’t know if I have ever wanted anything as much as I wanted to leave Austin and go live with my dad. My mother married three times over the next eight years. Like everyone else, she made some bad decisions. The first two stepfathers beat the hell out of my mother. Kristin and I would crouch in the hallway just off the living room. I wasn’t old enough to do anything to them physically. We’d just sit there with our backs against the wall listening to the violence. No child should have to live through that. We watched one man after another come into her life, and each one of them did the same thing.

My mother protected herself as best she could. Incredibly, she took care of us and made sure we never endured what she did. In every other way, my mom took care of us and never complained. She worked as many as three jobs and held together what little we had. She was a great mom, but sometimes stuff happens. Everybody makes bad decisions here and there. That’s life. My mom was a hairdresser and she’d put in as many hours as possible, sometimes working at two different salons. When she wasn’t doing hair, my mom cleaned houses and did whatever it took to make ends meet.

I’m sure all those men beating up my mother contributed to my desire to leave, but all I remember is crying a lot. It was just one incident after another. I don’t know how we became so dysfunctional that we allowed bad people into our lives. Maybe we attracted them in some way we didn’t realize. Maybe my mother had so much guilt about one thing or another that she felt like she didn’t deserve anything better. I remember one time, my mom and second stepdad came home, and both of them were getting out of the truck fighting. Jack and my mother were screaming and yelling at each other. She swung at him and he was shoving my mother into the cab of the truck. She got out and took a swing at him and he grabbed her hand and yanked it backward and broke her finger. Her wedding ring flew off her finger out into the grass near the front of the house. She came inside the house crying. Her finger was bent to one side. It’s hard for a child to process that kind of scene. But as soon as he left I went outside. I must have spent four or five hours combing through the grass looking for that ring. Finally around nine or ten o’clock at night, I found the ring. I walked back inside and gave it to her. I was probably eight or nine years old, and the only comfort I could provide my mother was to find that ring.

Looking back, it seems strange that I was trying to find a symbol of a busted marriage that had just led to a broken finger. I didn’t know what else to do or how else to help. I don’t know whether my father knew what was happening to my mother. I don’t know whether he cared one way or another at the time. My father never failed to send us child support, but he was young and I really don’t know whether he gave a damn. Like I said, his life was rolling and on the upswing. He was hell-bent on making a name in the business, which he most certainly did.

After they divorced, my dad would roll into town from time to time and we would go to the events. Still, it wasn’t until I was eleven or twelve that I really understood he was famous, or that he did something different from all the other dads. That’s about the time I started watching the World Class Championship Wrestling out of Texas with the Von Erichs. Kerry Von Erich, the Modern Day Warrior, was big at that time. The Freebirds were big, too. I remember going to the Coliseum in downtown Austin to see my dad wrestle. I was probably about nine years old, and it was the first time I saw my dad perform live. I was running around the floor as the show was going on. I was so excited to see my dad, and there were all these people jumping up and down cheering for him. It was really cool seeing people react to my dad that way. It was the way I felt about him, too.

After the show ended, I walked up to the ring. I jumped up onto the apron and grabbed the ropes. That’s when I heard my dad’s booming voice. He was in the back behind the curtain. He came running out into the arena and started yelling. “Don’t you ever get into that wrestling ring again.” He was mad, and it was scary for a young boy. I mean, that was my dad. He scared me so much that I didn’t get back into a ring until I got my start a decade later. To this day I don’t know whether he was concerned about my safety, or he just didn’t want me ever to become comfortable with the idea of one day being in the business. I know one thing: I’ve never forgotten that experience. All I wanted was to be with my dad. It was as if all these people, all the fans in that arena and in cities all over the territories he worked, had more of him than I did. He was always good to us, but I wanted to be a larger part of his life. Many years later my daughter, Dakota, would come with her mother and me on the road. I always let her climb into the ring and bounce around with Hunter and Edge and just have fun.

As the years rolled on, my sister and I didn’t see a whole lot of our father. During Christmas, he would fly us to Tampa on Braniff Airlines. In the summer, we’d make the same trip again, this time staying for a month. That’s all we really saw of him. Even then he was gone working all the time. Once in a while we talked to him on the phone, but otherwise he was somewhere out in the world. When we did see him, the time passed so quickly that it seemed like within moments of our arrival it was time to turn around and go home. At Christmas we’d open our presents and, boom, a couple days would pass and we were headed back to the airport. He was never really there for us. Then again, this lifestyle comes with the territory. It’s more demanding than most people can imagine. He was a father when it came to child support and generally doing the right thing in terms of his responsibilities to us, but it was more of a formality. His life was so much bigger, and there wasn’t a whole lot of room left for us.

I don’t know why my dad chose his path, but he knew how to make just about everyone love him. It is awesome to see. As soon as I became conscious of it, I wanted to be a part of it all. I didn’t recognize the fact that sometimes the life is far from glamorous, or that the travel and physical toll can wear you down. Dusty Rhodes was my dad, and I was drawn to him in the same way a fan is. Meanwhile, his career just kept rising. It was like he could do no wrong, and all I saw was the wonder of it all. Everything was going for him and I wanted a life just like his. I wanted that experience. In some ways we were growing up together, though we remained far apart. It seemed like the older I got the bigger he became.

After my sophomore year at Lanier High School in Austin, my mother finally agreed to let me go live with my father. I’m sure she thought, “Okay, go find out for yourself what it’s really all about.” I was a tight end on my high school football team and I had a lot of friends, but I never stopped wanting to be with my dad.

He had a new family by then, and they were living in Charlotte, North Carolina. I had started to come into my own as a football player around that time, though football was more of my father’s idea than my own. I became a pretty good defensive tackle at East Mecklenburg High School, where I was known as Dusty Runnels. Everyone knew who my dad was, in part because longtime professional wrestler Gene Anderson’s son, Brad, was in the same school and played football, too. Both of us were far more passionate about wrestling than football or pretty much anything else outside of girls.

Prior to our junior season, we shaved our heads like the Road Warriors, Hawk and Animal. Every chance we had, Brad and I would do trampoline wrestling. We’d put on an entire show from start to finish. My girlfriend would videotape me pulling up to the house in my dad’s Mercedes as if I were arriving at the arena. I’d wear my dad’s robes. We’d have his replica title belts. We took time to create these elaborate setups, making the whole experience as real as possible. We each had our music playing as we came toward the trampoline, which was our ring.

I liked playing football, but I loved wrestling. I’m sure it had something to do with the idea of wanting to be with my dad. But he tried to keep me away from it, that’s for sure. I probably should have taken a football scholarship, gone to college, and earned a degree, because then I would have had something to fall back on if wrestling didn’t work out. Maybe that was my dad’s thinking. All I know is that I was blinded by the desire to be a part of his life. The fact that it’s such a hard life never entered my mind. All I know is that I had the fever.

Transitionwise, it wasn’t a big deal for me to move from Austin to Charlotte. I was a big kid and an athlete, so I didn’t have much trouble adjusting to a new school. But it was not what I expected. My dad was still gone much of the time. He is a great loving father and both of us have changed in so many ways over the years. But at the time, I wanted and needed him to be the nurturing kind of father. I thought everything was going to be exactly how I had pictured it all those years when I was living in Austin. I thought there would be more father-son time, more time to build a deeper relationship with him. Instead, he always seemed grumpy and grouchy, which I understand now. He was working a lot inside and outside the ring. He was doing double duty as the boss working with Jim Crockett Promotions at National Wrestling Alliance before it became World Championship Wrestling. He was booking the talent and pushing himself, which meant there were always guys pissed off at him for one reason or another. Some guys were unhappy because they weren’t working enough. Other guys were mad that someone else was getting pushed ahead of them. He had to hire and fire guys. That’s the way it worked. He had the heat coming down from the wrestlers, but he couldn’t cater to every person because he was pushing himself, too. He also was a huge star at the time. He was the American Dream, Dusty Rhodes. He was as big as anyone in professional wrestling. My dad had to be creative and tough at the same time because he knew how to draw crowds and make money. If a guy wasn’t on the same page, then he had to get rid of him. I’m sure he created enemies along the way. As hard as it had to be physically, the mental stress of working both ends of the business had to be exhausting.

I didn’t mind playing football, because he wanted me to play. Besides, I thought I’d be playing in front of my father every week. As it turned out, I hardly got to see him. When I did see him he was riding me about homework, girls, grades, or something else. It was a letdown, but I had my buddies, so life moved on.

Although I wanted nothing more than to follow my father into wrestling, he hadn’t yet smartened me up. I played football and wrestled during my last two years in high school, and I did very well. Despite poor grades, I had a bunch of scholarship offers. Tennessee, Utah, and Louisville were among the schools that recruited me. I decided on the University of Louisville, where Howard Schnellenberger had taken over the program. But my heart wasn’t in the game. I had my mind oriented in one direction. I wanted to follow in my dad’s footsteps.

Back then professional wrestlers were very serious about keeping everything a secret. It was like a religion. There were a couple bosses I had early on who told us that if we went out drinking and got into a fight, we’d better not lose or we’d be fired. In my dad’s time if you wrestled somebody, you couldn’t be seen out partying with that guy later on. They would show up in separate cars and they never gave away their secrets. There were always people who thought they knew a little bit about what happened in the ring, though. I’d hear kids at school say, “Aw, wrestling’s fake. Your father isn’t really doing anything. It’s all just fake.” I hated that word then, and I still hate it today. It really annoys me when somebody calls what we do fake. And I kicked more than a little butt as I got older because of that word. But my dad kept it so quiet. All those guys at the time used to speak their own language. They called it “carny,” and my dad and mother, then later my stepmother would discuss a match or something going on in the business in this language that only they and other wrestlers could understand. That’s how protective they were of the business. They were serious about it in a way that’s hard to imagine today. Over time I picked up the language and figured out what they were saying. Little by little I learned how to speak it as well. Now it’s a lost art.

Rappers sing or perform in a kind of carny language of their own. I still talk in carny with some of the veterans because I love it. I don’t know where it went, though. You talk carny to some of the young guys and they’re like, “What is he talking about?” These young guys should know this stuff because it’s part of the history of our business. That’s the way we were raised, using carny language to communicate inside and outside the ring. It was like our own secret society and everyone followed the rules. It was great. Some of the bosses back then, if you got caught riding with a guy you were doing an angle with, they’d fire you on the spot. I kayfabed all the time. That is the art of keeping it all real for the fans by staying in character at all times. If I was driving with a guy I was wrestling that night, I’d jump out of the car down the road from the arena so we could keep the angle pure. I couldn’t see doing it any other way. We took it very seriously. When Steve Austin and I had our run in the early 1990s, we were very cautious about being seen together. Today, guys who just wrestled on television are out having a beer together and no one thinks twice about it.

To this day I don’t really know why my father was against me getting into professional wrestling. Obviously he knew how hard the life could be and maybe he wanted something different, something better for his son. I think that’s why he pushed football so hard. But I didn’t want to do anything else. Midway through my senior year in high school, my father moved back to Dallas. My little brother, Cody, was only a baby when they left, so I stayed behind and finished up my school year. Then I packed up what little I had and drove to Dallas.

By then my father knew I wasn’t going to go to college to play football. He called me up one day and said, “Pick me up at the airport in Dallas. We have something to talk about.” The airport was about a forty-five-minute drive from our new house in Texas. He got into my truck and launched into a forty-five-minute crash course on professional wrestling. He not only smartened me up about the way everything operates, but he covered the business outside the ring and beyond the arena. I took it all in. I probably knew by that point that the outcomes were set up in advance, but he explained how angles were developed. I remember being so impressed by his business sense and creativity. He understood every corner of it. He clued me in to some of the private verbiage wrestlers used, the carny language, between themselves in the ring so fans wouldn’t understand.

“Tomorrow night I want you to be in Amarillo,” he said. “First, go to a sporting goods store and buy yourself a referee shirt and some black cotton pants. You are going to referee two matches.”

This was 1988 and I was nineteen years old. I did exactly as my father asked, stopping by the store, then driving 350 miles to Amarillo in my used red Jeep Comanche pickup. Everyone else, including my father, took a private jet. My dad wanted me to pay my dues, so I hit the road. He laid it all out in that speech. He told me that I had to work hard for anything I got. It was the first and only time he smartened me up about the business. He went through the whole deal and I just did what I was told.

In the second match I refereed, my pants split from the top of the front all the way around the back when I went down for the three-count. And there was nothing under there. I was holding up Rock-n-Roll Express’s hands and my privates were hanging out. All the boys were at the curtain watching to see how I would do. I thought I did a pretty good job, but then I saw Tommy Young, the head referee at that time, pointing down at my crotch. There I was, holding up Rock-n-Roll Express’s hands, and everything was just hanging out. I remember thinking, “Oh my God.” I came back through the curtain and it was like I parted the Red Sea. Everyone was lying on the floor laughing like crazy. That was how I got my start. I had never even been in a wrestling ring before that night.

That night I took my dad to the airport so he could fly back to Dallas. He gave me a few bucks for gas and I drove the 365 miles back home.

I made $20 that night.

© 2010 World Wrestling Entertainment

THE FEVER

I got the fever as a young boy growing up in the long shadows of a big man in Austin, Texas.

The American Dream, Dusty Rhodes, is my dad. As a young boy, all I knew was that my dad was gone all the time. For the most part, my mother, my sister Kristin, and I were left to fend for ourselves. I can remember being five or six years old and seeing my dad come home after a long trip. I was like any other small boy. I wanted to crawl all over my dad when he finally walked through the front door. But he was too tired and his body too sore.

Back then, wrestlers worked territories, and they were gone for months at a time. He might spend two or three weeks in one place, come home, then head off to Japan for a month or more. He would take us places and we would get time with him, but it was always cut short by his schedule. My dad was naturally charismatic and very smart. I certainly didn’t understand how smart he was about his career then, but as a little boy all I wanted was more time with him. He was larger than life to me.

Then, one day, he was gone for good. My parents divorced right around the time I entered first grade at a private Christian school in Austin. I didn’t get the chance to know him the way a young boy wants to know his father. I was seven years old when my parents divorced. I remember crying for hours at a time during the days, weeks, and months that followed his departure. Even though he was gone a lot before the divorce, I always knew he’d come walking into the house in his cowboy boots and hat. Divorce meant the exact opposite. My father was gone and he wasn’t ever coming back. In those days, his life was rolling along at one hundred miles an hour, and being home with family was the slowest part of his existence.

As his stature grew in the business, the shadow became larger and more difficult for me. I don’t know if I have ever wanted anything as much as I wanted to leave Austin and go live with my dad. My mother married three times over the next eight years. Like everyone else, she made some bad decisions. The first two stepfathers beat the hell out of my mother. Kristin and I would crouch in the hallway just off the living room. I wasn’t old enough to do anything to them physically. We’d just sit there with our backs against the wall listening to the violence. No child should have to live through that. We watched one man after another come into her life, and each one of them did the same thing.

My mother protected herself as best she could. Incredibly, she took care of us and made sure we never endured what she did. In every other way, my mom took care of us and never complained. She worked as many as three jobs and held together what little we had. She was a great mom, but sometimes stuff happens. Everybody makes bad decisions here and there. That’s life. My mom was a hairdresser and she’d put in as many hours as possible, sometimes working at two different salons. When she wasn’t doing hair, my mom cleaned houses and did whatever it took to make ends meet.

I’m sure all those men beating up my mother contributed to my desire to leave, but all I remember is crying a lot. It was just one incident after another. I don’t know how we became so dysfunctional that we allowed bad people into our lives. Maybe we attracted them in some way we didn’t realize. Maybe my mother had so much guilt about one thing or another that she felt like she didn’t deserve anything better. I remember one time, my mom and second stepdad came home, and both of them were getting out of the truck fighting. Jack and my mother were screaming and yelling at each other. She swung at him and he was shoving my mother into the cab of the truck. She got out and took a swing at him and he grabbed her hand and yanked it backward and broke her finger. Her wedding ring flew off her finger out into the grass near the front of the house. She came inside the house crying. Her finger was bent to one side. It’s hard for a child to process that kind of scene. But as soon as he left I went outside. I must have spent four or five hours combing through the grass looking for that ring. Finally around nine or ten o’clock at night, I found the ring. I walked back inside and gave it to her. I was probably eight or nine years old, and the only comfort I could provide my mother was to find that ring.

Looking back, it seems strange that I was trying to find a symbol of a busted marriage that had just led to a broken finger. I didn’t know what else to do or how else to help. I don’t know whether my father knew what was happening to my mother. I don’t know whether he cared one way or another at the time. My father never failed to send us child support, but he was young and I really don’t know whether he gave a damn. Like I said, his life was rolling and on the upswing. He was hell-bent on making a name in the business, which he most certainly did.

After they divorced, my dad would roll into town from time to time and we would go to the events. Still, it wasn’t until I was eleven or twelve that I really understood he was famous, or that he did something different from all the other dads. That’s about the time I started watching the World Class Championship Wrestling out of Texas with the Von Erichs. Kerry Von Erich, the Modern Day Warrior, was big at that time. The Freebirds were big, too. I remember going to the Coliseum in downtown Austin to see my dad wrestle. I was probably about nine years old, and it was the first time I saw my dad perform live. I was running around the floor as the show was going on. I was so excited to see my dad, and there were all these people jumping up and down cheering for him. It was really cool seeing people react to my dad that way. It was the way I felt about him, too.

After the show ended, I walked up to the ring. I jumped up onto the apron and grabbed the ropes. That’s when I heard my dad’s booming voice. He was in the back behind the curtain. He came running out into the arena and started yelling. “Don’t you ever get into that wrestling ring again.” He was mad, and it was scary for a young boy. I mean, that was my dad. He scared me so much that I didn’t get back into a ring until I got my start a decade later. To this day I don’t know whether he was concerned about my safety, or he just didn’t want me ever to become comfortable with the idea of one day being in the business. I know one thing: I’ve never forgotten that experience. All I wanted was to be with my dad. It was as if all these people, all the fans in that arena and in cities all over the territories he worked, had more of him than I did. He was always good to us, but I wanted to be a larger part of his life. Many years later my daughter, Dakota, would come with her mother and me on the road. I always let her climb into the ring and bounce around with Hunter and Edge and just have fun.

As the years rolled on, my sister and I didn’t see a whole lot of our father. During Christmas, he would fly us to Tampa on Braniff Airlines. In the summer, we’d make the same trip again, this time staying for a month. That’s all we really saw of him. Even then he was gone working all the time. Once in a while we talked to him on the phone, but otherwise he was somewhere out in the world. When we did see him, the time passed so quickly that it seemed like within moments of our arrival it was time to turn around and go home. At Christmas we’d open our presents and, boom, a couple days would pass and we were headed back to the airport. He was never really there for us. Then again, this lifestyle comes with the territory. It’s more demanding than most people can imagine. He was a father when it came to child support and generally doing the right thing in terms of his responsibilities to us, but it was more of a formality. His life was so much bigger, and there wasn’t a whole lot of room left for us.

I don’t know why my dad chose his path, but he knew how to make just about everyone love him. It is awesome to see. As soon as I became conscious of it, I wanted to be a part of it all. I didn’t recognize the fact that sometimes the life is far from glamorous, or that the travel and physical toll can wear you down. Dusty Rhodes was my dad, and I was drawn to him in the same way a fan is. Meanwhile, his career just kept rising. It was like he could do no wrong, and all I saw was the wonder of it all. Everything was going for him and I wanted a life just like his. I wanted that experience. In some ways we were growing up together, though we remained far apart. It seemed like the older I got the bigger he became.

After my sophomore year at Lanier High School in Austin, my mother finally agreed to let me go live with my father. I’m sure she thought, “Okay, go find out for yourself what it’s really all about.” I was a tight end on my high school football team and I had a lot of friends, but I never stopped wanting to be with my dad.

He had a new family by then, and they were living in Charlotte, North Carolina. I had started to come into my own as a football player around that time, though football was more of my father’s idea than my own. I became a pretty good defensive tackle at East Mecklenburg High School, where I was known as Dusty Runnels. Everyone knew who my dad was, in part because longtime professional wrestler Gene Anderson’s son, Brad, was in the same school and played football, too. Both of us were far more passionate about wrestling than football or pretty much anything else outside of girls.

Prior to our junior season, we shaved our heads like the Road Warriors, Hawk and Animal. Every chance we had, Brad and I would do trampoline wrestling. We’d put on an entire show from start to finish. My girlfriend would videotape me pulling up to the house in my dad’s Mercedes as if I were arriving at the arena. I’d wear my dad’s robes. We’d have his replica title belts. We took time to create these elaborate setups, making the whole experience as real as possible. We each had our music playing as we came toward the trampoline, which was our ring.

I liked playing football, but I loved wrestling. I’m sure it had something to do with the idea of wanting to be with my dad. But he tried to keep me away from it, that’s for sure. I probably should have taken a football scholarship, gone to college, and earned a degree, because then I would have had something to fall back on if wrestling didn’t work out. Maybe that was my dad’s thinking. All I know is that I was blinded by the desire to be a part of his life. The fact that it’s such a hard life never entered my mind. All I know is that I had the fever.

Transitionwise, it wasn’t a big deal for me to move from Austin to Charlotte. I was a big kid and an athlete, so I didn’t have much trouble adjusting to a new school. But it was not what I expected. My dad was still gone much of the time. He is a great loving father and both of us have changed in so many ways over the years. But at the time, I wanted and needed him to be the nurturing kind of father. I thought everything was going to be exactly how I had pictured it all those years when I was living in Austin. I thought there would be more father-son time, more time to build a deeper relationship with him. Instead, he always seemed grumpy and grouchy, which I understand now. He was working a lot inside and outside the ring. He was doing double duty as the boss working with Jim Crockett Promotions at National Wrestling Alliance before it became World Championship Wrestling. He was booking the talent and pushing himself, which meant there were always guys pissed off at him for one reason or another. Some guys were unhappy because they weren’t working enough. Other guys were mad that someone else was getting pushed ahead of them. He had to hire and fire guys. That’s the way it worked. He had the heat coming down from the wrestlers, but he couldn’t cater to every person because he was pushing himself, too. He also was a huge star at the time. He was the American Dream, Dusty Rhodes. He was as big as anyone in professional wrestling. My dad had to be creative and tough at the same time because he knew how to draw crowds and make money. If a guy wasn’t on the same page, then he had to get rid of him. I’m sure he created enemies along the way. As hard as it had to be physically, the mental stress of working both ends of the business had to be exhausting.

I didn’t mind playing football, because he wanted me to play. Besides, I thought I’d be playing in front of my father every week. As it turned out, I hardly got to see him. When I did see him he was riding me about homework, girls, grades, or something else. It was a letdown, but I had my buddies, so life moved on.

Although I wanted nothing more than to follow my father into wrestling, he hadn’t yet smartened me up. I played football and wrestled during my last two years in high school, and I did very well. Despite poor grades, I had a bunch of scholarship offers. Tennessee, Utah, and Louisville were among the schools that recruited me. I decided on the University of Louisville, where Howard Schnellenberger had taken over the program. But my heart wasn’t in the game. I had my mind oriented in one direction. I wanted to follow in my dad’s footsteps.

Back then professional wrestlers were very serious about keeping everything a secret. It was like a religion. There were a couple bosses I had early on who told us that if we went out drinking and got into a fight, we’d better not lose or we’d be fired. In my dad’s time if you wrestled somebody, you couldn’t be seen out partying with that guy later on. They would show up in separate cars and they never gave away their secrets. There were always people who thought they knew a little bit about what happened in the ring, though. I’d hear kids at school say, “Aw, wrestling’s fake. Your father isn’t really doing anything. It’s all just fake.” I hated that word then, and I still hate it today. It really annoys me when somebody calls what we do fake. And I kicked more than a little butt as I got older because of that word. But my dad kept it so quiet. All those guys at the time used to speak their own language. They called it “carny,” and my dad and mother, then later my stepmother would discuss a match or something going on in the business in this language that only they and other wrestlers could understand. That’s how protective they were of the business. They were serious about it in a way that’s hard to imagine today. Over time I picked up the language and figured out what they were saying. Little by little I learned how to speak it as well. Now it’s a lost art.

Rappers sing or perform in a kind of carny language of their own. I still talk in carny with some of the veterans because I love it. I don’t know where it went, though. You talk carny to some of the young guys and they’re like, “What is he talking about?” These young guys should know this stuff because it’s part of the history of our business. That’s the way we were raised, using carny language to communicate inside and outside the ring. It was like our own secret society and everyone followed the rules. It was great. Some of the bosses back then, if you got caught riding with a guy you were doing an angle with, they’d fire you on the spot. I kayfabed all the time. That is the art of keeping it all real for the fans by staying in character at all times. If I was driving with a guy I was wrestling that night, I’d jump out of the car down the road from the arena so we could keep the angle pure. I couldn’t see doing it any other way. We took it very seriously. When Steve Austin and I had our run in the early 1990s, we were very cautious about being seen together. Today, guys who just wrestled on television are out having a beer together and no one thinks twice about it.

To this day I don’t really know why my father was against me getting into professional wrestling. Obviously he knew how hard the life could be and maybe he wanted something different, something better for his son. I think that’s why he pushed football so hard. But I didn’t want to do anything else. Midway through my senior year in high school, my father moved back to Dallas. My little brother, Cody, was only a baby when they left, so I stayed behind and finished up my school year. Then I packed up what little I had and drove to Dallas.

By then my father knew I wasn’t going to go to college to play football. He called me up one day and said, “Pick me up at the airport in Dallas. We have something to talk about.” The airport was about a forty-five-minute drive from our new house in Texas. He got into my truck and launched into a forty-five-minute crash course on professional wrestling. He not only smartened me up about the way everything operates, but he covered the business outside the ring and beyond the arena. I took it all in. I probably knew by that point that the outcomes were set up in advance, but he explained how angles were developed. I remember being so impressed by his business sense and creativity. He understood every corner of it. He clued me in to some of the private verbiage wrestlers used, the carny language, between themselves in the ring so fans wouldn’t understand.

“Tomorrow night I want you to be in Amarillo,” he said. “First, go to a sporting goods store and buy yourself a referee shirt and some black cotton pants. You are going to referee two matches.”

This was 1988 and I was nineteen years old. I did exactly as my father asked, stopping by the store, then driving 350 miles to Amarillo in my used red Jeep Comanche pickup. Everyone else, including my father, took a private jet. My dad wanted me to pay my dues, so I hit the road. He laid it all out in that speech. He told me that I had to work hard for anything I got. It was the first and only time he smartened me up about the business. He went through the whole deal and I just did what I was told.

In the second match I refereed, my pants split from the top of the front all the way around the back when I went down for the three-count. And there was nothing under there. I was holding up Rock-n-Roll Express’s hands and my privates were hanging out. All the boys were at the curtain watching to see how I would do. I thought I did a pretty good job, but then I saw Tommy Young, the head referee at that time, pointing down at my crotch. There I was, holding up Rock-n-Roll Express’s hands, and everything was just hanging out. I remember thinking, “Oh my God.” I came back through the curtain and it was like I parted the Red Sea. Everyone was lying on the floor laughing like crazy. That was how I got my start. I had never even been in a wrestling ring before that night.

That night I took my dad to the airport so he could fly back to Dallas. He gave me a few bucks for gas and I drove the 365 miles back home.

I made $20 that night.

© 2010 World Wrestling Entertainment

Descriere

A compelling insight into one of the most famous families in the history of the WWE as told by Dustin Rhodes, first son of the legendary Dusty Rhodes