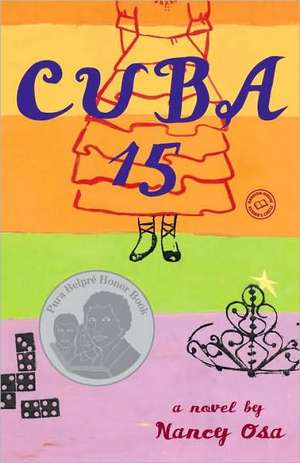

Cuba 15: Random House Reader's Circle

Autor Nancy Osaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2005 – vârsta de la 12 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Pura Belpre Award (2004), Delaware Diamonds Award (2008)

From the Hardcover edition.

Din seria Random House Reader's Circle

-

Preț: 107.68 lei

Preț: 107.68 lei -

Preț: 100.16 lei

Preț: 100.16 lei -

Preț: 74.62 lei

Preț: 74.62 lei -

Preț: 111.29 lei

Preț: 111.29 lei -

Preț: 108.72 lei

Preț: 108.72 lei -

Preț: 117.39 lei

Preț: 117.39 lei -

Preț: 139.68 lei

Preț: 139.68 lei -

Preț: 103.03 lei

Preț: 103.03 lei -

Preț: 65.10 lei

Preț: 65.10 lei -

Preț: 95.48 lei

Preț: 95.48 lei -

Preț: 98.78 lei

Preț: 98.78 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 128.86 lei

Preț: 128.86 lei -

Preț: 81.80 lei

Preț: 81.80 lei -

Preț: 128.64 lei

Preț: 128.64 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 120.71 lei

Preț: 120.71 lei -

Preț: 94.23 lei

Preț: 94.23 lei -

Preț: 125.84 lei

Preț: 125.84 lei -

Preț: 106.42 lei

Preț: 106.42 lei -

Preț: 100.83 lei

Preț: 100.83 lei -

Preț: 102.86 lei

Preț: 102.86 lei -

Preț: 128.33 lei

Preț: 128.33 lei -

Preț: 103.44 lei

Preț: 103.44 lei -

Preț: 115.49 lei

Preț: 115.49 lei -

Preț: 122.14 lei

Preț: 122.14 lei -

Preț: 105.22 lei

Preț: 105.22 lei -

Preț: 115.08 lei

Preț: 115.08 lei -

Preț: 119.55 lei

Preț: 119.55 lei -

Preț: 108.90 lei

Preț: 108.90 lei -

Preț: 115.34 lei

Preț: 115.34 lei -

Preț: 116.76 lei

Preț: 116.76 lei -

Preț: 124.72 lei

Preț: 124.72 lei -

Preț: 159.17 lei

Preț: 159.17 lei -

Preț: 91.55 lei

Preț: 91.55 lei -

Preț: 104.59 lei

Preț: 104.59 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 104.66 lei

Preț: 104.66 lei -

Preț: 117.80 lei

Preț: 117.80 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 104.81 lei

Preț: 104.81 lei -

Preț: 108.50 lei

Preț: 108.50 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 98.21 lei

Preț: 98.21 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 135.15 lei

Preț: 135.15 lei -

Preț: 122.45 lei

Preț: 122.45 lei -

Preț: 139.15 lei

Preț: 139.15 lei -

Preț: 98.12 lei

Preț: 98.12 lei

Preț: 57.77 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 87

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.06€ • 11.50$ • 9.13£

11.06€ • 11.50$ • 9.13£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Livrare express 11-15 martie pentru 20.45 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385732338

ISBN-10: 0385732333

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Ember

Seria Random House Reader's Circle

ISBN-10: 0385732333

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Ember

Seria Random House Reader's Circle

Extras

1

What can be funny about having to stand up in front of everyone you know, in a ruffly dress the color of Pepto-Bismol, and proclaim your womanhood? Nothing. Nada. Zip. Not when you’re fifteen—too young to drive, win the lottery, or vote for a president who might lower the driving and gambling ages. Nothing funny at all. At least that’s what I thought in September.

My—womanhoods—hadn’t even begun to grow; I wore a bra size so small they’d named it with lowercase letters: aaa. Guys avoided me like the feminine hygiene aisle at the grocery store. And I never wore dresses. Not since I’d left school uniforms behind. Not ever, no exceptions. You’d think my own grandmother would remember that.

She didn’t.

“Eh, Violet, m’ija. I want buy you a gown and make you a ’keen-say’ party,” my grandmother said early that September morning in her customized English, shrewdly springing her idea on me at breakfast.

“Sounds good, Abuela,” I said as I buttered my muffin. “Except for the dress.”

Just Abuela, my little brother, Mark, and I were up; Abuelo, tired from traveling, was sleeping in, and Mom never got up until after Mark and I had left for school. Thrift store worker’s hours. Mom ran the Rise & Walk Thrift Sanctuary, a used-clothing shop in the church basement that operates on donations. Their motto is “The Threads Shall Walk Again.” Dad was on the early shift at the twenty-four-hour pharmacy inside the Lincolnville Food Depot, a combination grocery store/bank/hairdresser/veterinary hospital/pharmacy/service station. All they needed now was a tattoo parlor.

“What’s ’keent-sy’?” Mark asked, adding, “I want one too!”

“The quince,” said Abuela, “this is short for quincea-ero, the fifteenth birthday in Cuba.” She pronounced it

“Coo-ba,” the Spanish way. “Is a ceremony only for the girls,” she added, shaking a finger at Mark, who tipped his cereal bowl toward his mouth to get the last of the sugary milk at the bottom.

He swallowed. “That’s sexist, Abuela. Only for girls.” He tried another pass at his cereal bowl, but it was empty. “I know, because last year in my school on Take Your Daughters to Work Day, Father Leone said sons got to go to work too. So I got out of school!”

Abuela, looking starched somehow in one of Mom’s old terry cloth robes, her silver hair in a bun, raised an eyebrow and gave a wry smile. “This is equality, yes?”

She often says yes when she means no, and vice versa.

“The quincea-ero, m’ijo, this is the time when the girl becomes the woman.”

Mark, who was eleven then, shied away from any discussion that even hinted at having to do with body parts or workings. He turned corpuscle red, a nice counterpoint to his royal blue Cubs baseball cap, which he wore all day every day during the pro season, except in school and church, until the end of the last game of the World Series. The fringe of his dark hair stuck out in a ragged halo around his face. He immediately lost interest in the quince party. “Nevermind, countmeout,” he mumbled.

Abuela didn’t notice. “The quince is the time when all the resto del mundo ass-cepts your dear sister as an adult in the eyes of God and family. And she, in turn, promises to ass-cept responsabilidad for all the wonders in the world of adults.”

Responsabilidad. This sank in as deeply as the Country Crock into the nooks and crannies of my half-eaten English muffin, and raised a red flag. This quince party could be some sort of trap. “What if I don’t want to—ass-cept more responsibilities?” I asked, mindlessly mimicking Abuela’s pronunciation.

Mark slipped away, leaving his empty cereal bowl and milk glass on the table.

Abuela sat down with a tiny cup of sweet, black coffee. “Responsabilidades—how do you say? These come with the territory, chiquitica.” She downed her coffee in one shot.

I pointed to Mark’s dirty bowl. “How about his responsibilities?”

She shrugged and motioned for me to clear his place.

“Now that’s sexist,” I grumbled, stomping off to the sink with Mark’s dishes and my own.

Abuela said something that rhymed in Spanish, then translated: “The bull cannot make the milk, and the cow alone cannot make the bull.”

I kissed her, shaking my head, and left for school. There’s no sense arguing with the fundamentals.

Leda Lundquist stood waiting for me outside Spanish class. My friend Leda is as slim as a sunflower and admirably as tall, though not quite as seedy. She has long, straight, pale-pale blond hair and white-white skin with just the faintest glow to indicate that blood does run through her veins.

“Yo, Paz,” she said to me at the door, with her usual lack of finesse. “Come away with me this weekend.”

“Don’t you have a boyfriend for that, Leed?” I asked, sweeping past her and into the last row of seats.

Leda set down her gym duffel and books and sat beside me, braiding her hair into an orderly rope. She wore a giant turquoise tie-dyed T-shirt as a dress, belted with a rolled-up bandana. Rubber flip-flops and a pink plastic Slinky on one arm for a bracelet completed her back-to-school look. “I have got the perfect fund-raiser for you—for us—to go to Saturday afternoon.”

I groaned. “No way,” I said, before she had a chance to state her case.

“C-U-B-A” was all she said, and she waited for my reaction.

I raised my eyebrows in a let-me-have-it look.

“The Cuba Caravan’s coming through town. Isn’t your dad going? There’s gonna be a dance, and a send-off, and—”

I shook my head no, and harder for no way. I didn’t want to stir up that kettle of Caribbean fish. The subject of Cuba was best left unmentioned around Dad. “Forget it, Leda,” I said, wondering how many times I’d been caught up in this constant refusal of invitations since we’d first met. With the Lundquists’ raft of causes, most weekends offered at least one political demonstration for the family to enjoy.

“—and even a raffle, Paz, what could be better than that? Besides . . .”

She paused.

“Besides what?”

“Well . . . if we stand around long enough, you might meet some hunky Cuban guys at the salsa dance . . . and I could top a thousand bucks in the walkabout fund.”

Aha. The true motive. Leda was speaking of the European adventure fund that her parents pay into every time she goes to some activist thing with them—double if she brings a friend. By the time she turns eighteen, Leda plans to have enough money to traipse across Europe and several other continents, solo.

Which was why we, lofty sophomore creatures that we were, presently found ourselves in the back row of Se-ora Wong’s freshman Spanish class, trying not to be noticed. It had been Leda’s idea to take the first year of each language offered at Tri-District High so she’d be able to speak a little of the native tongue no matter where she roamed. Last year, merci beaucoup, it had been French. I didn’t care which language I learned, so I tagged along for the fun of it.

Se-ora Wong, diminutive but not fragile, ruled with an ironic fist. “Leona, Violeta, could you find it in your hearts to join the rest of us?” she asked, calling us by our Spanish-class names, hitting just the right note of sarcasm. She went on to show the class the same list of easy nouns that Leda and I learned last year at this time: casa, sombrero, estudiante—only last year it was in French.

From the Hardcover edition.

What can be funny about having to stand up in front of everyone you know, in a ruffly dress the color of Pepto-Bismol, and proclaim your womanhood? Nothing. Nada. Zip. Not when you’re fifteen—too young to drive, win the lottery, or vote for a president who might lower the driving and gambling ages. Nothing funny at all. At least that’s what I thought in September.

My—womanhoods—hadn’t even begun to grow; I wore a bra size so small they’d named it with lowercase letters: aaa. Guys avoided me like the feminine hygiene aisle at the grocery store. And I never wore dresses. Not since I’d left school uniforms behind. Not ever, no exceptions. You’d think my own grandmother would remember that.

She didn’t.

“Eh, Violet, m’ija. I want buy you a gown and make you a ’keen-say’ party,” my grandmother said early that September morning in her customized English, shrewdly springing her idea on me at breakfast.

“Sounds good, Abuela,” I said as I buttered my muffin. “Except for the dress.”

Just Abuela, my little brother, Mark, and I were up; Abuelo, tired from traveling, was sleeping in, and Mom never got up until after Mark and I had left for school. Thrift store worker’s hours. Mom ran the Rise & Walk Thrift Sanctuary, a used-clothing shop in the church basement that operates on donations. Their motto is “The Threads Shall Walk Again.” Dad was on the early shift at the twenty-four-hour pharmacy inside the Lincolnville Food Depot, a combination grocery store/bank/hairdresser/veterinary hospital/pharmacy/service station. All they needed now was a tattoo parlor.

“What’s ’keent-sy’?” Mark asked, adding, “I want one too!”

“The quince,” said Abuela, “this is short for quincea-ero, the fifteenth birthday in Cuba.” She pronounced it

“Coo-ba,” the Spanish way. “Is a ceremony only for the girls,” she added, shaking a finger at Mark, who tipped his cereal bowl toward his mouth to get the last of the sugary milk at the bottom.

He swallowed. “That’s sexist, Abuela. Only for girls.” He tried another pass at his cereal bowl, but it was empty. “I know, because last year in my school on Take Your Daughters to Work Day, Father Leone said sons got to go to work too. So I got out of school!”

Abuela, looking starched somehow in one of Mom’s old terry cloth robes, her silver hair in a bun, raised an eyebrow and gave a wry smile. “This is equality, yes?”

She often says yes when she means no, and vice versa.

“The quincea-ero, m’ijo, this is the time when the girl becomes the woman.”

Mark, who was eleven then, shied away from any discussion that even hinted at having to do with body parts or workings. He turned corpuscle red, a nice counterpoint to his royal blue Cubs baseball cap, which he wore all day every day during the pro season, except in school and church, until the end of the last game of the World Series. The fringe of his dark hair stuck out in a ragged halo around his face. He immediately lost interest in the quince party. “Nevermind, countmeout,” he mumbled.

Abuela didn’t notice. “The quince is the time when all the resto del mundo ass-cepts your dear sister as an adult in the eyes of God and family. And she, in turn, promises to ass-cept responsabilidad for all the wonders in the world of adults.”

Responsabilidad. This sank in as deeply as the Country Crock into the nooks and crannies of my half-eaten English muffin, and raised a red flag. This quince party could be some sort of trap. “What if I don’t want to—ass-cept more responsibilities?” I asked, mindlessly mimicking Abuela’s pronunciation.

Mark slipped away, leaving his empty cereal bowl and milk glass on the table.

Abuela sat down with a tiny cup of sweet, black coffee. “Responsabilidades—how do you say? These come with the territory, chiquitica.” She downed her coffee in one shot.

I pointed to Mark’s dirty bowl. “How about his responsibilities?”

She shrugged and motioned for me to clear his place.

“Now that’s sexist,” I grumbled, stomping off to the sink with Mark’s dishes and my own.

Abuela said something that rhymed in Spanish, then translated: “The bull cannot make the milk, and the cow alone cannot make the bull.”

I kissed her, shaking my head, and left for school. There’s no sense arguing with the fundamentals.

Leda Lundquist stood waiting for me outside Spanish class. My friend Leda is as slim as a sunflower and admirably as tall, though not quite as seedy. She has long, straight, pale-pale blond hair and white-white skin with just the faintest glow to indicate that blood does run through her veins.

“Yo, Paz,” she said to me at the door, with her usual lack of finesse. “Come away with me this weekend.”

“Don’t you have a boyfriend for that, Leed?” I asked, sweeping past her and into the last row of seats.

Leda set down her gym duffel and books and sat beside me, braiding her hair into an orderly rope. She wore a giant turquoise tie-dyed T-shirt as a dress, belted with a rolled-up bandana. Rubber flip-flops and a pink plastic Slinky on one arm for a bracelet completed her back-to-school look. “I have got the perfect fund-raiser for you—for us—to go to Saturday afternoon.”

I groaned. “No way,” I said, before she had a chance to state her case.

“C-U-B-A” was all she said, and she waited for my reaction.

I raised my eyebrows in a let-me-have-it look.

“The Cuba Caravan’s coming through town. Isn’t your dad going? There’s gonna be a dance, and a send-off, and—”

I shook my head no, and harder for no way. I didn’t want to stir up that kettle of Caribbean fish. The subject of Cuba was best left unmentioned around Dad. “Forget it, Leda,” I said, wondering how many times I’d been caught up in this constant refusal of invitations since we’d first met. With the Lundquists’ raft of causes, most weekends offered at least one political demonstration for the family to enjoy.

“—and even a raffle, Paz, what could be better than that? Besides . . .”

She paused.

“Besides what?”

“Well . . . if we stand around long enough, you might meet some hunky Cuban guys at the salsa dance . . . and I could top a thousand bucks in the walkabout fund.”

Aha. The true motive. Leda was speaking of the European adventure fund that her parents pay into every time she goes to some activist thing with them—double if she brings a friend. By the time she turns eighteen, Leda plans to have enough money to traipse across Europe and several other continents, solo.

Which was why we, lofty sophomore creatures that we were, presently found ourselves in the back row of Se-ora Wong’s freshman Spanish class, trying not to be noticed. It had been Leda’s idea to take the first year of each language offered at Tri-District High so she’d be able to speak a little of the native tongue no matter where she roamed. Last year, merci beaucoup, it had been French. I didn’t care which language I learned, so I tagged along for the fun of it.

Se-ora Wong, diminutive but not fragile, ruled with an ironic fist. “Leona, Violeta, could you find it in your hearts to join the rest of us?” she asked, calling us by our Spanish-class names, hitting just the right note of sarcasm. She went on to show the class the same list of easy nouns that Leda and I learned last year at this time: casa, sombrero, estudiante—only last year it was in French.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Violet’s hilarious cool first-person narrative veers between farce and tenderness, denial and truth . . .”—Booklist, Starred

“Cuba 15 will make readers laugh, whether or not their families are as loco as Violet’s.”—The Horn Book Magazine

A Pura Belpré Honor Book

An ALA Notable Book

An ALA Best Book for Young Adults

A Booklist Top Ten Youth First Novels

“Cuba 15 will make readers laugh, whether or not their families are as loco as Violet’s.”—The Horn Book Magazine

A Pura Belpré Honor Book

An ALA Notable Book

An ALA Best Book for Young Adults

A Booklist Top Ten Youth First Novels

Descriere

The 2001 winner of the Delacorte Press Prize for a First Young Adult Novel tells the story of a girl who while preparing for her 15th year celebration--her "quince"--probes into her Cuban roots and unwittingly unleashes a hotbed of conflicted feelings about Cuba within her family. Young Adult.

Notă biografică

Nancy Osa

Premii

- Pura Belpre Award Honor Book, 2004

- Delaware Diamonds Award Nominee, 2008