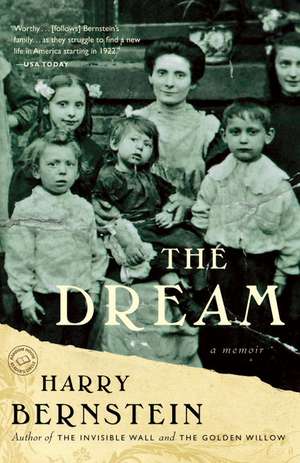

The Dream: A Memoir: Random House Reader's Circle

Autor Harry Bernsteinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2009

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 100.30 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| BALLANTINE BOOKS – 31 mar 2009 | 111.29 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| CORNERSTONE – 30 apr 2008 | 100.30 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Din seria Random House Reader's Circle

-

Preț: 107.68 lei

Preț: 107.68 lei -

Preț: 100.16 lei

Preț: 100.16 lei -

Preț: 74.62 lei

Preț: 74.62 lei -

Preț: 108.72 lei

Preț: 108.72 lei -

Preț: 117.39 lei

Preț: 117.39 lei -

Preț: 139.68 lei

Preț: 139.68 lei -

Preț: 103.03 lei

Preț: 103.03 lei -

Preț: 65.10 lei

Preț: 65.10 lei -

Preț: 57.77 lei

Preț: 57.77 lei -

Preț: 95.48 lei

Preț: 95.48 lei -

Preț: 98.78 lei

Preț: 98.78 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 128.86 lei

Preț: 128.86 lei -

Preț: 81.80 lei

Preț: 81.80 lei -

Preț: 128.64 lei

Preț: 128.64 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 120.71 lei

Preț: 120.71 lei -

Preț: 94.23 lei

Preț: 94.23 lei -

Preț: 125.84 lei

Preț: 125.84 lei -

Preț: 106.42 lei

Preț: 106.42 lei -

Preț: 100.83 lei

Preț: 100.83 lei -

Preț: 102.86 lei

Preț: 102.86 lei -

Preț: 128.33 lei

Preț: 128.33 lei -

Preț: 103.44 lei

Preț: 103.44 lei -

Preț: 115.49 lei

Preț: 115.49 lei -

Preț: 122.14 lei

Preț: 122.14 lei -

Preț: 105.22 lei

Preț: 105.22 lei -

Preț: 115.08 lei

Preț: 115.08 lei -

Preț: 119.55 lei

Preț: 119.55 lei -

Preț: 108.90 lei

Preț: 108.90 lei -

Preț: 115.34 lei

Preț: 115.34 lei -

Preț: 116.76 lei

Preț: 116.76 lei -

Preț: 124.72 lei

Preț: 124.72 lei -

Preț: 159.17 lei

Preț: 159.17 lei -

Preț: 91.55 lei

Preț: 91.55 lei -

Preț: 104.59 lei

Preț: 104.59 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 104.66 lei

Preț: 104.66 lei -

Preț: 117.80 lei

Preț: 117.80 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 104.81 lei

Preț: 104.81 lei -

Preț: 108.50 lei

Preț: 108.50 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 98.21 lei

Preț: 98.21 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 135.15 lei

Preț: 135.15 lei -

Preț: 122.45 lei

Preț: 122.45 lei -

Preț: 139.15 lei

Preț: 139.15 lei -

Preț: 98.12 lei

Preț: 98.12 lei

Preț: 111.29 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 167

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.30€ • 22.15$ • 17.58£

21.30€ • 22.15$ • 17.58£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345503893

ISBN-10: 0345503899

Pagini: 279

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Random House Reader's Circle

ISBN-10: 0345503899

Pagini: 279

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Random House Reader's Circle

Notă biografică

Ninety-eight-year-old Harry Bernstein emigrated to the United States with his family after World War I. He began writing his acclaimed first book, The Invisible Wall, after the death of his wife, Ruby. He has also been published in “My Turn” in Newsweek. Bernstein lives in Brick, New Jersey, where he is working on another book.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Dreams played an important part in our lives in those early days in England. Our mother invented them for us to make up for all the things we lacked and to give us some hope for the future. Perhaps, also, it was for herself, to escape the miseries she had to endure, which were caused chiefly by my father, who cared little about his family.

The dreams were always there to brighten our lives a little. Only they came and went, beautiful while they lasted, but fragile and quick to vanish. They were like the soap bubbles we used to blow out of a clay pipe, sending them floating in the air above us in a gay, colorful procession, each one tantalizing but elusive. When we reached up to seize one and hold it in our hand, it burst at the slightest touch and disappeared. That is how our dreams were.

Take, for instance, the front parlor. For years and years, as long as we had lived in the house, the front room, intended to be a parlor, had remained empty, completely without furniture of any sort, simply because we could not afford to buy any. The fireplace had never been lit, and stood there cold and gray. But that wasn’t how it appeared in the dream my mother conjured up for us. It would, she promised, be warm and cozy, with red plush furniture, a luxurious divan, and big, comfortable chairs. It would have a red plush carpet on the floor too, and on top of all that there would be a piano. Yes, a piano with black and white keys that we could all play on.

Oh, it was a wonderful dream, and we used to pretend it had already happened and we were lounging on the chairs, with my sister Rose stretched out on the divan. She, more than any of us, gave vent to a vivid imagination, playing the part of a duchess and giving commands to servants in a haughty tone, with an imaginary lorgnette held to her eyes.

Then what happened? My mother must have done a lot of soul searching, and it must have cost her many a sleepless night before she reached her decision to do what Rose afterward, in her bitterness, called treachery. But what else could my poor mother have done? She was struggling desperately to keep us all alive with the little money my father doled out to her every week from his pay as a tailor, keeping the bulk of it for his drinking and gambling. She had to do something to keep us from starving, so she turned the front room into a small shop, where she sold faded fruits and vegetables, which she scavenged from underneath the stalls in the market.

A common shop, no less, to break that beautiful bubble. My sister Rose never forgave her, and indeed the bitterness and resentment lasted a lifetime, and she hardly ever talked to my mother again.

But that’s how our dreams were, and it didn’t seem as if the really big one my mother had would be any different. This was the dream of going to America. This was the one my mother would never give up. It was the panacea for all her ills, the only hope she had left of a better life.

We had relatives there–not hers; she had none of her own, having been orphaned as a child in Poland, then passed from one unwilling and often unkind household to another until she was sixteen and able to make her way to England. They were my father’s relatives, his father and mother, and about ten brothers and sisters, a large brood of which he was the oldest.

At one time they too had lived in England, and in the very same house where we now lived, that whole family crowded into a house that was scarcely big enough for ours with only six children. No wonder they fought so often among themselves; it was for space, probably, they fought, although they fought with their neighbors as well. They were a noisy, unruly lot, I am told, and my father was the worst of them all when it came to battling. In fact, he terrorized his entire family with his loud voice and ready fists; even my grandmother may have been afraid of him, and she was pretty tough herself.

As for my grandfather, he played no part in any of this. He let my grandmother rule the house, which she did with an iron fist except when it came to my father. But my grandfather managed to keep pretty much to himself. He was a roofer by trade and he was away often, mending slate roofs in distant towns and enjoying himself immensely. He would sing while he worked, songs of all nationalities, Jewish, Irish, English, Polish, often drawing a large, appreciative audience below.

In an old cardboard box where my mother used to keep an assortment of family photographs I once found a sepia photo of my father’s entire family, all of them arranged in three rows one behind the other, all dressed in their best clothes, smiling and looking like well-behaved, perfectly respectable children, far from the ruffians that they were. In the center sat the two parents, my grandmother heavy and double-chinned with a massive bosom and the glower on her face that was always there. Beside her sat my grandfather, a bearded and quite distinguished-looking gentleman holding a silver-knobbed cane between his legs, wearing a frock coat.

My father was not in that photograph, and for a very good reason: He was still in Poland.

The story, I have always felt, was somewhat apocryphal, yet older members of the family swear to its truth. At seven years of age my father had been put to work in a slaughterhouse, where he cleared up the remains of the animals that had been slaughtered for butchering. He worked twelve and sometimes more hours a day. At nine he started to drink. At ten he was defying my grandmother and a terror to all of them. He could not be handled. So one day while he was at work my grandmother gathered up the rest of her children and together with my grandfather they all fled to England, leaving my father to fend for himself. When he got home and found them gone, he almost went mad with rage. He followed them, however, and after many difficult weeks of travel finally got to England. He arrived at our street in the middle of the night, having learned from other Jewish people where they lived, and he banged on the door and demanded to be let in.

My grandmother was awakened along with the rest of the household. Peering down from her bedroom window and seeing who it was, she went to get the bucket that stood on the landing and was used as a toilet for the night. It was full to the brim. She carried it to the open window and poured it down on his head. He let out a yell of rage, but refused to give up and kept banging on the door until she was forced to let him in.

So now it was the same thing all over again, except that he was vengeful and more dangerous than ever, and my grandmother racked her brain for another means of getting rid of him. It was at this time, so the story goes, that my mother arrived in England and straight into the hands of my grandmother, who immediately saw the solution to her problem in this sweet, innocent young orphaned girl, who had no friends, no relatives, nobody in the world to turn to. It was not hard to promote the match between her and my father, so my mother, knowing nothing about him, fell into the trap of a marriage that brought her nothing but misery for the rest of her life.

That wasn’t the end of the story. No sooner had this marriage taken place than my grandmother lost no time in putting as much distance as she could between her and her oldest son. Once again she packed her things, gathered her brood together, and took them off to America, and out of the goodness of her heart she arranged with the landlord for the newly married couple to take over her house.

In view of all this it would seem utterly useless for my mother to appeal to my father’s family–my grandmother, especially–for help in coming to America. Twice they had fled from my father. What chance was there that they would spend their money to buy the steamship tickets that she always asked for and that would bring him back into their lives?

Yet, knowing this, knowing the terrible story of how they had abandoned him in Poland and the suspicion that it had been something similar when they went to America, my mother wrote to all of them just the same. By this time the children were grown up, and most of them were married and out of my grandmother’s house, so there were many letters to write.

She could not write herself, since she had never gone to school; she dictated them to one of us. Through all the years this had been going on, the job was handed down from one to the other as we grew up, until finally it came to me, and I was the one who sat down opposite her at the table in the kitchen and dipped my pen in the ink bottle and waited while she thought of what to say.

At last she began: “My dear–––,” naming whomever this was being written to. “Just a few lines to let you know we are all well and hoping to hear the same from you.”

Her letters always began this way, and eventually, after a few words of gossip about the old street–how Mrs. Cohen had had another baby, how this one across the street had been sick, how that one had lost a job–she would finally launch into her plea for the tickets. She never said the word money. She could not bear the thought of taking money from anyone. But tickets, steamship tickets, seemed better, and she would always reassure them that they would be paid for once we got to America and started working there.

They did not always answer. Sometimes weeks would go by and no letter came from America. The postman knew all about us and what we were expecting. Well, the whole street knew, but the postman especially. He was an elderly man with white hair sticking out from under his peaked hat, and he limped from a wounded leg he had got in the Boer War. He’d see me waiting at the front door while he limped his way down the street with his bag slung over one shoulder, and shake his head before he got to me and say, “Not today, lad. Better luck tomorrow.”

We did get a letter from Uncle Abe. And it was an excited, jubilant letter. He wrote telling us how well he was doing, that he had three suits of clothing hanging in his closet. In his excitement his words got twisted a little, and one sentence came out as “I have a beautiful home and a wife with electric lights and a bathtub.”

It was good for a laugh, but what about the tickets we’d asked him for? Nor did any of the others mention them. And as for my grandmother, the one letter she wrote in several years had a caustic touch. “What do you think I am,” she asked, “the Bank of England? Or do you think I took the crown jewels with me when I left England?”

With all this you’d think my mother would get discouraged and give up writing letters. But that did not happen, and I don’t know how many letters I wrote over the years, starting when I was about nine or ten. And then one morning when I was twelve, while we were all seated round the table at breakfast, there was a loud knocking at the front door.

“Go and see who it is,” my mother said, addressing no one in particular. She was too busy serving the breakfast and trying to feed the baby, who was propped up in an improvised high chair made from an ordinary chair plus a wooden box and a strap.

For a while none of us seemed to have heard her. It was probably a Jewish holiday of some sort, for we were all home and my father was still upstairs sleeping. We were busy not only eating but also reading, with our books and magazines propped up in front of us against the sugar bowl, the milk jug, the loaf of bread, or whatever other support we could find. This was a regular practice of ours at mealtimes. But the lack of response to my mother’s request could have been due to something else. Despite the absorption in our reading, it could have been the thought that the knock might be from a customer, and that would have been a good reason to ignore it. We hated customers along with the shop, still not realizing that it represented our very lifeblood.

And then my eyes lifted from the copy of Treasure Island that I was reading, and my mother’s gaze caught mine and she said, “You go, Harry.”

I got up reluctantly and went to the front door.

From the Hardcover edition.

Dreams played an important part in our lives in those early days in England. Our mother invented them for us to make up for all the things we lacked and to give us some hope for the future. Perhaps, also, it was for herself, to escape the miseries she had to endure, which were caused chiefly by my father, who cared little about his family.

The dreams were always there to brighten our lives a little. Only they came and went, beautiful while they lasted, but fragile and quick to vanish. They were like the soap bubbles we used to blow out of a clay pipe, sending them floating in the air above us in a gay, colorful procession, each one tantalizing but elusive. When we reached up to seize one and hold it in our hand, it burst at the slightest touch and disappeared. That is how our dreams were.

Take, for instance, the front parlor. For years and years, as long as we had lived in the house, the front room, intended to be a parlor, had remained empty, completely without furniture of any sort, simply because we could not afford to buy any. The fireplace had never been lit, and stood there cold and gray. But that wasn’t how it appeared in the dream my mother conjured up for us. It would, she promised, be warm and cozy, with red plush furniture, a luxurious divan, and big, comfortable chairs. It would have a red plush carpet on the floor too, and on top of all that there would be a piano. Yes, a piano with black and white keys that we could all play on.

Oh, it was a wonderful dream, and we used to pretend it had already happened and we were lounging on the chairs, with my sister Rose stretched out on the divan. She, more than any of us, gave vent to a vivid imagination, playing the part of a duchess and giving commands to servants in a haughty tone, with an imaginary lorgnette held to her eyes.

Then what happened? My mother must have done a lot of soul searching, and it must have cost her many a sleepless night before she reached her decision to do what Rose afterward, in her bitterness, called treachery. But what else could my poor mother have done? She was struggling desperately to keep us all alive with the little money my father doled out to her every week from his pay as a tailor, keeping the bulk of it for his drinking and gambling. She had to do something to keep us from starving, so she turned the front room into a small shop, where she sold faded fruits and vegetables, which she scavenged from underneath the stalls in the market.

A common shop, no less, to break that beautiful bubble. My sister Rose never forgave her, and indeed the bitterness and resentment lasted a lifetime, and she hardly ever talked to my mother again.

But that’s how our dreams were, and it didn’t seem as if the really big one my mother had would be any different. This was the dream of going to America. This was the one my mother would never give up. It was the panacea for all her ills, the only hope she had left of a better life.

We had relatives there–not hers; she had none of her own, having been orphaned as a child in Poland, then passed from one unwilling and often unkind household to another until she was sixteen and able to make her way to England. They were my father’s relatives, his father and mother, and about ten brothers and sisters, a large brood of which he was the oldest.

At one time they too had lived in England, and in the very same house where we now lived, that whole family crowded into a house that was scarcely big enough for ours with only six children. No wonder they fought so often among themselves; it was for space, probably, they fought, although they fought with their neighbors as well. They were a noisy, unruly lot, I am told, and my father was the worst of them all when it came to battling. In fact, he terrorized his entire family with his loud voice and ready fists; even my grandmother may have been afraid of him, and she was pretty tough herself.

As for my grandfather, he played no part in any of this. He let my grandmother rule the house, which she did with an iron fist except when it came to my father. But my grandfather managed to keep pretty much to himself. He was a roofer by trade and he was away often, mending slate roofs in distant towns and enjoying himself immensely. He would sing while he worked, songs of all nationalities, Jewish, Irish, English, Polish, often drawing a large, appreciative audience below.

In an old cardboard box where my mother used to keep an assortment of family photographs I once found a sepia photo of my father’s entire family, all of them arranged in three rows one behind the other, all dressed in their best clothes, smiling and looking like well-behaved, perfectly respectable children, far from the ruffians that they were. In the center sat the two parents, my grandmother heavy and double-chinned with a massive bosom and the glower on her face that was always there. Beside her sat my grandfather, a bearded and quite distinguished-looking gentleman holding a silver-knobbed cane between his legs, wearing a frock coat.

My father was not in that photograph, and for a very good reason: He was still in Poland.

The story, I have always felt, was somewhat apocryphal, yet older members of the family swear to its truth. At seven years of age my father had been put to work in a slaughterhouse, where he cleared up the remains of the animals that had been slaughtered for butchering. He worked twelve and sometimes more hours a day. At nine he started to drink. At ten he was defying my grandmother and a terror to all of them. He could not be handled. So one day while he was at work my grandmother gathered up the rest of her children and together with my grandfather they all fled to England, leaving my father to fend for himself. When he got home and found them gone, he almost went mad with rage. He followed them, however, and after many difficult weeks of travel finally got to England. He arrived at our street in the middle of the night, having learned from other Jewish people where they lived, and he banged on the door and demanded to be let in.

My grandmother was awakened along with the rest of the household. Peering down from her bedroom window and seeing who it was, she went to get the bucket that stood on the landing and was used as a toilet for the night. It was full to the brim. She carried it to the open window and poured it down on his head. He let out a yell of rage, but refused to give up and kept banging on the door until she was forced to let him in.

So now it was the same thing all over again, except that he was vengeful and more dangerous than ever, and my grandmother racked her brain for another means of getting rid of him. It was at this time, so the story goes, that my mother arrived in England and straight into the hands of my grandmother, who immediately saw the solution to her problem in this sweet, innocent young orphaned girl, who had no friends, no relatives, nobody in the world to turn to. It was not hard to promote the match between her and my father, so my mother, knowing nothing about him, fell into the trap of a marriage that brought her nothing but misery for the rest of her life.

That wasn’t the end of the story. No sooner had this marriage taken place than my grandmother lost no time in putting as much distance as she could between her and her oldest son. Once again she packed her things, gathered her brood together, and took them off to America, and out of the goodness of her heart she arranged with the landlord for the newly married couple to take over her house.

In view of all this it would seem utterly useless for my mother to appeal to my father’s family–my grandmother, especially–for help in coming to America. Twice they had fled from my father. What chance was there that they would spend their money to buy the steamship tickets that she always asked for and that would bring him back into their lives?

Yet, knowing this, knowing the terrible story of how they had abandoned him in Poland and the suspicion that it had been something similar when they went to America, my mother wrote to all of them just the same. By this time the children were grown up, and most of them were married and out of my grandmother’s house, so there were many letters to write.

She could not write herself, since she had never gone to school; she dictated them to one of us. Through all the years this had been going on, the job was handed down from one to the other as we grew up, until finally it came to me, and I was the one who sat down opposite her at the table in the kitchen and dipped my pen in the ink bottle and waited while she thought of what to say.

At last she began: “My dear–––,” naming whomever this was being written to. “Just a few lines to let you know we are all well and hoping to hear the same from you.”

Her letters always began this way, and eventually, after a few words of gossip about the old street–how Mrs. Cohen had had another baby, how this one across the street had been sick, how that one had lost a job–she would finally launch into her plea for the tickets. She never said the word money. She could not bear the thought of taking money from anyone. But tickets, steamship tickets, seemed better, and she would always reassure them that they would be paid for once we got to America and started working there.

They did not always answer. Sometimes weeks would go by and no letter came from America. The postman knew all about us and what we were expecting. Well, the whole street knew, but the postman especially. He was an elderly man with white hair sticking out from under his peaked hat, and he limped from a wounded leg he had got in the Boer War. He’d see me waiting at the front door while he limped his way down the street with his bag slung over one shoulder, and shake his head before he got to me and say, “Not today, lad. Better luck tomorrow.”

We did get a letter from Uncle Abe. And it was an excited, jubilant letter. He wrote telling us how well he was doing, that he had three suits of clothing hanging in his closet. In his excitement his words got twisted a little, and one sentence came out as “I have a beautiful home and a wife with electric lights and a bathtub.”

It was good for a laugh, but what about the tickets we’d asked him for? Nor did any of the others mention them. And as for my grandmother, the one letter she wrote in several years had a caustic touch. “What do you think I am,” she asked, “the Bank of England? Or do you think I took the crown jewels with me when I left England?”

With all this you’d think my mother would get discouraged and give up writing letters. But that did not happen, and I don’t know how many letters I wrote over the years, starting when I was about nine or ten. And then one morning when I was twelve, while we were all seated round the table at breakfast, there was a loud knocking at the front door.

“Go and see who it is,” my mother said, addressing no one in particular. She was too busy serving the breakfast and trying to feed the baby, who was propped up in an improvised high chair made from an ordinary chair plus a wooden box and a strap.

For a while none of us seemed to have heard her. It was probably a Jewish holiday of some sort, for we were all home and my father was still upstairs sleeping. We were busy not only eating but also reading, with our books and magazines propped up in front of us against the sugar bowl, the milk jug, the loaf of bread, or whatever other support we could find. This was a regular practice of ours at mealtimes. But the lack of response to my mother’s request could have been due to something else. Despite the absorption in our reading, it could have been the thought that the knock might be from a customer, and that would have been a good reason to ignore it. We hated customers along with the shop, still not realizing that it represented our very lifeblood.

And then my eyes lifted from the copy of Treasure Island that I was reading, and my mother’s gaze caught mine and she said, “You go, Harry.”

I got up reluctantly and went to the front door.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Worthy . . . [follows] Bernstein’s family . . . as they struggle to find a new life in America in 1922.”—USA Today

“Packed with carefully crafted dialogue and descriptions that transport us, with keen verisimilitude, from working-class England to Depression-era Chicago . . . Visceral, honest writing [makes] Bernstein’s memoir impossible to put down.”—Jewish News Weekly

“[A] wise, unsentimental memoir.”—New York Times

“Beneath the poignant descriptions of places and times past, beneath the rising and falling patterns of these characters’ lives, we hear what Wordsworth called ‘the still sad music of humanity.’ ”—Washington Post Book World

“Gripping . . . a powerful story of courage, sacrifice, determination, financial hardship and love.”—Jewish Chronicle

“This little book is a marvel, sparely written by a man with almost 100 years experience.”—Deseret Morning News

“Packed with carefully crafted dialogue and descriptions that transport us, with keen verisimilitude, from working-class England to Depression-era Chicago . . . Visceral, honest writing [makes] Bernstein’s memoir impossible to put down.”—Jewish News Weekly

“[A] wise, unsentimental memoir.”—New York Times

“Beneath the poignant descriptions of places and times past, beneath the rising and falling patterns of these characters’ lives, we hear what Wordsworth called ‘the still sad music of humanity.’ ”—Washington Post Book World

“Gripping . . . a powerful story of courage, sacrifice, determination, financial hardship and love.”—Jewish Chronicle

“This little book is a marvel, sparely written by a man with almost 100 years experience.”—Deseret Morning News

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

On a narrow cobbled street in a northern mill town young Harry Bernstein and his family face a daily struggle to make ends meet.

On a narrow cobbled street in a northern mill town young Harry Bernstein and his family face a daily struggle to make ends meet.