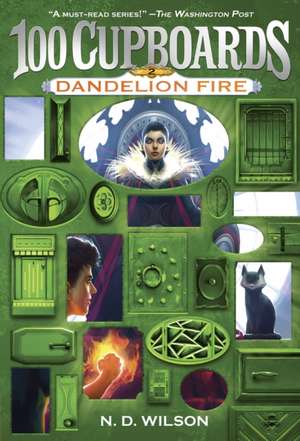

Dandelion Fire: 100 Cupboards, cartea 02

Autor N. D. Wilsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 1899 – vârsta de la 8 până la 12 ani

N. D. Wilson and his wife live in Idaho. Also visit www.ndwilson.com.

From the Hardcover edition.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 50.56 lei 3-4 săpt. | +21.72 lei 7-11 zile |

| Yearling Books – 31 dec 1899 | 50.56 lei 3-4 săpt. | +21.72 lei 7-11 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 143.67 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| TURTLEBACK BOOKS – 30 noi 2009 | 143.67 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 50.56 lei

Preț vechi: 58.65 lei

-14% Nou

Puncte Express: 76

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.68€ • 9.100$ • 8.05£

9.68€ • 9.100$ • 8.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-11 martie

Livrare express 18-22 februarie pentru 31.71 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375838842

ISBN-10: 0375838848

Pagini: 466

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 133 x 194 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

Seria 100 Cupboards

ISBN-10: 0375838848

Pagini: 466

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 133 x 194 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

Seria 100 Cupboards

Notă biografică

N. D. WILSON lives and writes in the top of a tall, skinny house only one block from where he was born. But his bestselling novels, including the highly acclaimed 100 Cupboards series, have traveled far and wide and have been translated into dozens of languages. He and his wife have five young storytellers of their own, along with an unreasonable number of pets. You can visit him online at ndwilson.com.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

Kansas is not easily impressed. It has seen houses fly and cattle soar. When funnel clouds walk through the wheat, big hail falls behind. As the biggest stones melt, turtles and mice and fish and even men can be seen frozen inside. And Kansas is not surprised.

Henry York had seen things in Kansas, things he didn’t think belonged in this world. Things that didn’t. Kansas hadn’t flinched.

The soles of Henry’s shoes were twenty feet off the ground. He had managed to slide open the heavy door in the barn loft, and after brushing the rust and flakes of red paint off his hands, he’d seated himself on the dust-covered planks and looked out over the ripening fields. Henry’s feet dangled, but Kansas sprawled.

Henry had changed in the short weeks since he’d stepped off the bus from Boston, been smothered by Aunt Dotty and taken to the old farmhouse, to the attic—to a new existence. He looked different, too, and it wasn’t just the cut across the backs of his fingers. That was scarring worse than it needed to only because he couldn’t stop himself from picking at it. The burns on his jaw were a lot more noticeable and had begun scarring as well. He didn’t like touching them. But he had to. Especially the one below his ear. It was turning into a divot as wide as his fingertip.

What had changed most about Henry York was inside his head. Things he had always known no longer seemed true. A world that had always felt like a slow and stable and even boring machine had suddenly come to life. And it was far from tame. He’d uncovered a wall of doors in his attic room, and now he didn’t know who he was. He didn’t know who his real parents were or whether he was even in the right world. He didn’t really know anything. Strangely, that was more comfortable than thinking that he did.

One month before, fresh off the bus from Boston, he would have been nervous sitting where he was, slowly bouncing his heels on the wall of the barn. One month before, he wouldn’t have believed that he could hit a baseball. Something wheezed beside him, and Henry turned. One month before, the world was still normal, and creatures like this one didn’t exist.

The raggant sniffed loudly and settled onto his haunches. His wings were tucked back against his rough charcoal skin and his blunt horn was, as always, lifted in the air.

Henry smiled. He always did when he looked at the animal. It was so proud and so very unaware of how it looked. At least Henry thought it had to be. Shaped like a small basset hound but wearing wings and a rhino’s face and skin, it was far from beautiful, but that didn’t stop it from being as proud and stubborn as a peacock. Like an otherworldly bloodhound, it had found Henry, cracking the plaster in the attic wall from inside a cupboard. The raggant had started everything. Whoever it was that had sent the raggant had started everything. Henry couldn’t even imagine who that might be.

“Do you know how strange you look?” Henry asked, and he reached over and grabbed the loose skin on the creature’s neck. It felt like sand-based dough, and as he squeezed, the raggant closed its black eyes and a low moan sputtered in its chest.

“I want to see you fly,” Henry said. “You know I will.” He glanced down at the ground and then back at the raggant. He could push it. Then it would have to fly. But it just might be proud enough not to, proud enough to tuck its wings tight and bounce in the tall grass. “Sometime,” Henry said.

The afternoon sun was falling, and Henry knew it wouldn’t be long before the barn’s shadow stretched across acres. Worse, it wouldn’t be long before the fields and the barn and all of Kansas became part of his past. His parents had been back from their ill-fated bicycle trip for a while, and he still hadn’t heard from them. That wasn’t too unusual. When they were just getting back from their photographed adventures, he rarely ever heard from them. The fact that they’d actually managed to get kidnapped this time would make their return crazier, would keep him safely off their minds for that much longer. But it couldn’t last. If they’d had any say in the matter, he never would have been sent to stay with his cousins at all. Now that they’d returned, they wouldn’t leave him in Kansas for school or even through the summer. He’d be back in Boston, on some new vitamin diet and meeting a new nanny, and then back to boarding school. Maybe a new one. His third.

Parents. He still thought of them that way. Would they ever have told him that Grandfather had found him in the attic? Not likely. Henry didn’t care that he’d been adopted. But it was hard not to care that his parents had never really been parents—not like Uncle Frank and Aunt Dotty were to his cousins. Henry had always known exactly where he was on his parents’ list of priorities.

Yesterday, he’d seen his parents on television. He’d been stirring his cereal and listening to his youngest cousin, Anastasia, complain about Richard when Uncle Frank called him. He’d hurried, and when he stepped into the room, Frank pointed. There, on a stiff couch in a television studio somewhere, sat Phillip and Ursula, smiling and nodding. They each had hands crossed on their knees. Ursula kept glancing at the camera. She looked like Henry’s aunt Dotty, but with all her edges hardened. The two of them talked about their amazing endurance, the difficulty of bicycling through the Andes, how they had never given up hope of finishing their trek even after being abducted in Colombia, the size of their book deal, and their discussions with film agents.

In a general way, Henry remembered all they had said. But there were two things that sat in the front of his mind, every syllable in concrete.

“Are you closer now?” the woman had asked them. “After going through all of this together?”

Ursula had leaned forward. Phillip had leaned back. “You know,” Ursula had said. “We’ve both changed a great deal during this whole process. We really need to get to know each other again. But first we need to get to know ourselves.”

Phillip had nodded.

Henry was pretty sure he knew what that meant.

And then the woman had asked about him.

From the Hardcover edition.

Kansas is not easily impressed. It has seen houses fly and cattle soar. When funnel clouds walk through the wheat, big hail falls behind. As the biggest stones melt, turtles and mice and fish and even men can be seen frozen inside. And Kansas is not surprised.

Henry York had seen things in Kansas, things he didn’t think belonged in this world. Things that didn’t. Kansas hadn’t flinched.

The soles of Henry’s shoes were twenty feet off the ground. He had managed to slide open the heavy door in the barn loft, and after brushing the rust and flakes of red paint off his hands, he’d seated himself on the dust-covered planks and looked out over the ripening fields. Henry’s feet dangled, but Kansas sprawled.

Henry had changed in the short weeks since he’d stepped off the bus from Boston, been smothered by Aunt Dotty and taken to the old farmhouse, to the attic—to a new existence. He looked different, too, and it wasn’t just the cut across the backs of his fingers. That was scarring worse than it needed to only because he couldn’t stop himself from picking at it. The burns on his jaw were a lot more noticeable and had begun scarring as well. He didn’t like touching them. But he had to. Especially the one below his ear. It was turning into a divot as wide as his fingertip.

What had changed most about Henry York was inside his head. Things he had always known no longer seemed true. A world that had always felt like a slow and stable and even boring machine had suddenly come to life. And it was far from tame. He’d uncovered a wall of doors in his attic room, and now he didn’t know who he was. He didn’t know who his real parents were or whether he was even in the right world. He didn’t really know anything. Strangely, that was more comfortable than thinking that he did.

One month before, fresh off the bus from Boston, he would have been nervous sitting where he was, slowly bouncing his heels on the wall of the barn. One month before, he wouldn’t have believed that he could hit a baseball. Something wheezed beside him, and Henry turned. One month before, the world was still normal, and creatures like this one didn’t exist.

The raggant sniffed loudly and settled onto his haunches. His wings were tucked back against his rough charcoal skin and his blunt horn was, as always, lifted in the air.

Henry smiled. He always did when he looked at the animal. It was so proud and so very unaware of how it looked. At least Henry thought it had to be. Shaped like a small basset hound but wearing wings and a rhino’s face and skin, it was far from beautiful, but that didn’t stop it from being as proud and stubborn as a peacock. Like an otherworldly bloodhound, it had found Henry, cracking the plaster in the attic wall from inside a cupboard. The raggant had started everything. Whoever it was that had sent the raggant had started everything. Henry couldn’t even imagine who that might be.

“Do you know how strange you look?” Henry asked, and he reached over and grabbed the loose skin on the creature’s neck. It felt like sand-based dough, and as he squeezed, the raggant closed its black eyes and a low moan sputtered in its chest.

“I want to see you fly,” Henry said. “You know I will.” He glanced down at the ground and then back at the raggant. He could push it. Then it would have to fly. But it just might be proud enough not to, proud enough to tuck its wings tight and bounce in the tall grass. “Sometime,” Henry said.

The afternoon sun was falling, and Henry knew it wouldn’t be long before the barn’s shadow stretched across acres. Worse, it wouldn’t be long before the fields and the barn and all of Kansas became part of his past. His parents had been back from their ill-fated bicycle trip for a while, and he still hadn’t heard from them. That wasn’t too unusual. When they were just getting back from their photographed adventures, he rarely ever heard from them. The fact that they’d actually managed to get kidnapped this time would make their return crazier, would keep him safely off their minds for that much longer. But it couldn’t last. If they’d had any say in the matter, he never would have been sent to stay with his cousins at all. Now that they’d returned, they wouldn’t leave him in Kansas for school or even through the summer. He’d be back in Boston, on some new vitamin diet and meeting a new nanny, and then back to boarding school. Maybe a new one. His third.

Parents. He still thought of them that way. Would they ever have told him that Grandfather had found him in the attic? Not likely. Henry didn’t care that he’d been adopted. But it was hard not to care that his parents had never really been parents—not like Uncle Frank and Aunt Dotty were to his cousins. Henry had always known exactly where he was on his parents’ list of priorities.

Yesterday, he’d seen his parents on television. He’d been stirring his cereal and listening to his youngest cousin, Anastasia, complain about Richard when Uncle Frank called him. He’d hurried, and when he stepped into the room, Frank pointed. There, on a stiff couch in a television studio somewhere, sat Phillip and Ursula, smiling and nodding. They each had hands crossed on their knees. Ursula kept glancing at the camera. She looked like Henry’s aunt Dotty, but with all her edges hardened. The two of them talked about their amazing endurance, the difficulty of bicycling through the Andes, how they had never given up hope of finishing their trek even after being abducted in Colombia, the size of their book deal, and their discussions with film agents.

In a general way, Henry remembered all they had said. But there were two things that sat in the front of his mind, every syllable in concrete.

“Are you closer now?” the woman had asked them. “After going through all of this together?”

Ursula had leaned forward. Phillip had leaned back. “You know,” Ursula had said. “We’ve both changed a great deal during this whole process. We really need to get to know each other again. But first we need to get to know ourselves.”

Phillip had nodded.

Henry was pretty sure he knew what that meant.

And then the woman had asked about him.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Henry York never dreamed his time in Kansas would open a door to adventure--much less a hundred doors. Now Henry must follow the trail through the cupboards to find the truth about who he really is.