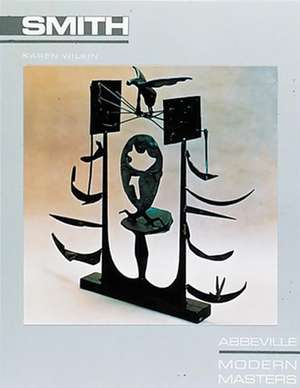

David Smith: Modern Masters Series

Autor Karen Wilkinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 1984

Having realized quite early that he had to be an artist, Smith made his way to New York and the Art Students League. There he experimented with variations on the revealing styles of Cubism and Surrealism, and slowly discovered his own technique, particularly the use of industrial methods such as welding to construct his sculptures. The results — though responsive to such varied influences as Picasso and pin-up girls — were imaginative, and often strikingly beautiful. Smith's art has inspired generations of followers, but his position as one of the masters of 20th-century sculpture remains unchallenged.

About the Modern Masters series:

With informative, enjoyable texts and over 100 illustrations — approximately 48 in full color — this innovative series offers a fresh look at the most creative and influential artists of the postwar era. The authors are highly respected art historians and critics chosen for their ability to think clearly and write well. Each handsomely designed volume presents a thorough survey of the artist's life and work, as well as statements by the artist, an illustrated chapter on technique, a chronology, lists of exhibitions and public collections, an annotated bibliography, and an index. Every art lover, from the casual museumgoer to the serious student, teacher, critic, or curator, will be eager to collect these Modern Masters. And with such a low price, they can afford to collect them all.

About the Modern Masters series:

With informative, enjoyable texts and over 100 illustrations — approximately 48 in full color — this innovative series offers a fresh look at the most creative and influential artists of the postwar era. The authors are highly respected art historians and critics chosen for their ability to think clearly and write well. Each handsomely designed volume presents a thorough survey of the artist's life and work, as well as statements by the artist, an illustrated chapter on technique, a chronology, lists of exhibitions and public collections, an annotated bibliography, and an index. Every art lover, from the casual museumgoer to the serious student, teacher, critic, or curator, will be eager to collect these Modern Masters. And with such a low price, they can afford to collect them all.

Preț: 100.28 lei

Preț vechi: 125.01 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 150

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.19€ • 20.09$ • 15.88£

19.19€ • 20.09$ • 15.88£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781558592568

ISBN-10: 1558592563

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 216 x 279 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.62 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Modern Masters Series

ISBN-10: 1558592563

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 216 x 279 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.62 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Modern Masters Series

Cuprins

Introduction 7

1. Early Life and Work 11

2. The 1940s 31

3. The 1950s 49

4. The 1960s 67

5. Sources and Successors 89

Artist's Statements 109

Notes on Technique 113

Chronology 117

Exhibitions 119

Public Collections 123

Selected Bibliography 124

Index 127

1. Early Life and Work 11

2. The 1940s 31

3. The 1950s 49

4. The 1960s 67

5. Sources and Successors 89

Artist's Statements 109

Notes on Technique 113

Chronology 117

Exhibitions 119

Public Collections 123

Selected Bibliography 124

Index 127

Recenzii

Praise for the Modern Masters series:

"Each author has thoroughly done his or her homework, knows the historical, critical and personal contexts intimately, and writes extraordinarily well." —Artnews

Notă biografică

Karen Wilkin—author of Abbeville's Stuart Davis and Georges Braque as well as many other monographs—is a free-lance curator and critic in New York.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

Every year David Smith's reputation grows a little. Every new showing of his work makes him loom larger, yet he remains an elusive artist. The idea of Smith is more present than the fact of his work. The full range of his achievement is still not widely known; his most familiar sculptures are not always his finest. Since about 1978, exhibitions ranging from drawings and paintings to little-known works have helped expand knowledge of Smith's art, but in spite of them, and in spite of a considerable body of writing on Smith, the myth of the larger-than-life American artist-hero seems to have been assimilated more fully than the work itself.

And yet, it is not altogether a myth. So much about Smith does seem larger than life: his genius, his protean energy, his gargantuan appetite for work, his ambition, his sheer physical size, even his premature death at a critical time in his career. Impressive, too, is the intensity of his sculpture, its undercurrents of violence and disguised sensuality. And the image of the fields surrounding his home at Bolton Landing, filled with rows of his challenging, potent sculpture, is unforgettable.

Smith himself could encourage misleading notions of his work and life, but many apparent contradictions are real. He earned his place in history of contemporary art as a sculptor in metal, yet he insisted that he "belonged with painters" and liked to point out that much of the best modern sculpture had been made by painters, citing Picasso, Matisse, and Degas. Smith's own formal training was as a painter; as a sculptor, he was virtually self-taught. Even after he had determined that he was primarily a sculptor, Smith never abandoned painting. His desire to fuse the two disciplines in colored structures that would, in his words, "beat either one," is well known, but perhaps more significantly, he drew and painted prodigiously throughout his working life. He concentrated on sculpture, and no one would deny that his most inventive and powerful efforts were in three dimensions, but there is also an enormous body of two-dimensional work in an impressive range of media. The same sort of omnivorous ambition led Smith to explore, at various times, the possibilities of cast bronze and aluminum, forged iron, ceramics, and, briefly, carved stone. He saw himself as a universal artist who transformed whatever he turned his hand to by the force of his individuality, yet he is generally thought to have been exclusively a sculptor in welded metal.

Generally, too, Smith is viewed as an anguished, lonely figure working in self-imposed exile, away from colleagues and contemporaries, in upstate New York. The anguish and loneliness were undoubtedly intense; they pervade Smith's writings and his friend's recollections of him, but so does an exuberant gregariousness. It is true that after 1940 Smith chose to live and work on a remote farm near Lake George, but he was hardly isolated. Friends and colleagues visited; he went to New York often. His work clearly demonstrates his awareness of current aesthetic concerns (just as it helped formulate what we now perceive as those concerns). It takes nothing away from Smith's originality to say that his sculpture obviously responds to and disputes with notions being promulgated at the time of its making. It is informed, sophisticated art, alert to its place in the history of sculpture, which gives the lie to the image of its maker as a reclusive autodidact.

Much of the writing on Smith emphasize his size and strength, the factory methods he used to make art, the sculpture's macho, heroic qualities. It's all true, of course, even if Smith was sometimes guilty of overemphasizing this side of his work. His own photographs of his sculptures that we have previously seen only in Smith's own images is often startling. The works are as notable for their delicacy and intimacy as for their power and size. The industrial antecedents of their methods and materials seem less important than the evidence of their maker's hand. Rather than the huge, declarative, flat sculpture that Smith's photographs have led us to expect, we are confronted by works of human scale, great subtlety, and remarkable spatial complexity.

If our ideas about Smith seem haunted by confusion, it is not always the fault of our perceptions. The work is astonishingly difficult. It is uningratiating and contradictory, resisting precise definitions. The best pieces are often at once radically abstract and uncannily anthropomorphic, aggressively robust and surprisingly sensitive. They seem to both exemplify and reinvent the vocabulary of Abstract Expressionism, to point back to Cubism and to anticipate concerns of the 1970s and '80s. Like their maker, they cannot easily be categorized.

Time and two generations of heirs to Smith's new tradition of sculpture have not lessened the impact of his work. It remains modern and challenging, even disturbing. Its evolution recapitulates the development of freestanding open construction from Cubist painting and collage, but two decades after Smith's death, his art still stakes out new territory for sculpture. Paradoxically, it seems to combine a tough-minded formal detachment with an overwhelming desire to achieve expressiveness, as though Smith worked with two contradictory attitudes. On the one hand, he appears to have been dispassionately alert to the possibilities that arose in the course of working, and on the other, intensely concerned with the invention—or discover—of personal metaphorical images.

Smith could be uncritical of his own production, not in the sense of being easily satisfied, but in insisting on the significance of everything he made as the declaration of a particular, special individual. In any case, he disliked critical distinctions: "The works you see are segments of my work life. If you prefer one work over another, it is your privilege, but it does not interest me. The work is a statement of identity, it comes from a stream, it is related to my past works, the three or four works in process and the work yet to come."

Every year David Smith's reputation grows a little. Every new showing of his work makes him loom larger, yet he remains an elusive artist. The idea of Smith is more present than the fact of his work. The full range of his achievement is still not widely known; his most familiar sculptures are not always his finest. Since about 1978, exhibitions ranging from drawings and paintings to little-known works have helped expand knowledge of Smith's art, but in spite of them, and in spite of a considerable body of writing on Smith, the myth of the larger-than-life American artist-hero seems to have been assimilated more fully than the work itself.

And yet, it is not altogether a myth. So much about Smith does seem larger than life: his genius, his protean energy, his gargantuan appetite for work, his ambition, his sheer physical size, even his premature death at a critical time in his career. Impressive, too, is the intensity of his sculpture, its undercurrents of violence and disguised sensuality. And the image of the fields surrounding his home at Bolton Landing, filled with rows of his challenging, potent sculpture, is unforgettable.

Smith himself could encourage misleading notions of his work and life, but many apparent contradictions are real. He earned his place in history of contemporary art as a sculptor in metal, yet he insisted that he "belonged with painters" and liked to point out that much of the best modern sculpture had been made by painters, citing Picasso, Matisse, and Degas. Smith's own formal training was as a painter; as a sculptor, he was virtually self-taught. Even after he had determined that he was primarily a sculptor, Smith never abandoned painting. His desire to fuse the two disciplines in colored structures that would, in his words, "beat either one," is well known, but perhaps more significantly, he drew and painted prodigiously throughout his working life. He concentrated on sculpture, and no one would deny that his most inventive and powerful efforts were in three dimensions, but there is also an enormous body of two-dimensional work in an impressive range of media. The same sort of omnivorous ambition led Smith to explore, at various times, the possibilities of cast bronze and aluminum, forged iron, ceramics, and, briefly, carved stone. He saw himself as a universal artist who transformed whatever he turned his hand to by the force of his individuality, yet he is generally thought to have been exclusively a sculptor in welded metal.

Generally, too, Smith is viewed as an anguished, lonely figure working in self-imposed exile, away from colleagues and contemporaries, in upstate New York. The anguish and loneliness were undoubtedly intense; they pervade Smith's writings and his friend's recollections of him, but so does an exuberant gregariousness. It is true that after 1940 Smith chose to live and work on a remote farm near Lake George, but he was hardly isolated. Friends and colleagues visited; he went to New York often. His work clearly demonstrates his awareness of current aesthetic concerns (just as it helped formulate what we now perceive as those concerns). It takes nothing away from Smith's originality to say that his sculpture obviously responds to and disputes with notions being promulgated at the time of its making. It is informed, sophisticated art, alert to its place in the history of sculpture, which gives the lie to the image of its maker as a reclusive autodidact.

Much of the writing on Smith emphasize his size and strength, the factory methods he used to make art, the sculpture's macho, heroic qualities. It's all true, of course, even if Smith was sometimes guilty of overemphasizing this side of his work. His own photographs of his sculptures that we have previously seen only in Smith's own images is often startling. The works are as notable for their delicacy and intimacy as for their power and size. The industrial antecedents of their methods and materials seem less important than the evidence of their maker's hand. Rather than the huge, declarative, flat sculpture that Smith's photographs have led us to expect, we are confronted by works of human scale, great subtlety, and remarkable spatial complexity.

If our ideas about Smith seem haunted by confusion, it is not always the fault of our perceptions. The work is astonishingly difficult. It is uningratiating and contradictory, resisting precise definitions. The best pieces are often at once radically abstract and uncannily anthropomorphic, aggressively robust and surprisingly sensitive. They seem to both exemplify and reinvent the vocabulary of Abstract Expressionism, to point back to Cubism and to anticipate concerns of the 1970s and '80s. Like their maker, they cannot easily be categorized.

Time and two generations of heirs to Smith's new tradition of sculpture have not lessened the impact of his work. It remains modern and challenging, even disturbing. Its evolution recapitulates the development of freestanding open construction from Cubist painting and collage, but two decades after Smith's death, his art still stakes out new territory for sculpture. Paradoxically, it seems to combine a tough-minded formal detachment with an overwhelming desire to achieve expressiveness, as though Smith worked with two contradictory attitudes. On the one hand, he appears to have been dispassionately alert to the possibilities that arose in the course of working, and on the other, intensely concerned with the invention—or discover—of personal metaphorical images.

Smith could be uncritical of his own production, not in the sense of being easily satisfied, but in insisting on the significance of everything he made as the declaration of a particular, special individual. In any case, he disliked critical distinctions: "The works you see are segments of my work life. If you prefer one work over another, it is your privilege, but it does not interest me. The work is a statement of identity, it comes from a stream, it is related to my past works, the three or four works in process and the work yet to come."