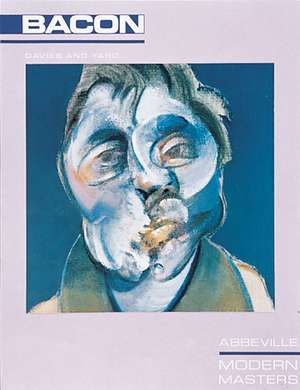

Francis Bacon: Modern Masters Series

Autor Hugh Marlais Davies Contribuţii de Sally Yarden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 1986

With their searing colors and compelling images, the paintings of Francis Bacon are among the most powerful, and the most poignant, to be made in the twentieth century.

During his sixty-odd years as a painter Francis Bacon fearlessly tackled the unruly imagery of life, remaining defiantly committed to giving "this purposeless existence a meaning." His insistence on depicting the mysteries of human experience had been rare in an age dominated by abstraction. Now, with the international resurgence of figurative imagery, the pivotal importance of his work has become more obvious than ever before.

The power and magnitude of his life's work are vividly conveyed by this thorough evaluation written by Hugh Davies and Sally Yard. Born in Dublin, as a teenager Bacon moved to London, where he worked as an interior designer and taught himself to paint. Responding to influences as diverse as Michelangelo and the photographer Muybridge, he has created a motion-filled style uniquely his own. Fascinated by the challenge of capturing what he calls "the mysteries of appearance," Bacon confronts us with emotional images that demand an emotional response.

About Abbeville's Modern Masters series:

With informative, enjoyable texts and over 100 illustrations—approximately 48 in full color—this innovative series offers a fresh look at the most creative and influential artists of the postwar era. The authors are highly respected art historians and critics chosen for their ability to think clearly and write well. Each handsomely designed volume presents a thorough survey of the artists life and work, as well as statements by the artist, an illustrated chapter on technique, a chronology, lists of exhibitions and public collections, an annotated bibliography, and an index. Every art lover, from the casual museum goer to the serious student, teacher, critic, or curator, will be eager to collect these Modern Masters. And with such a low price, they can afford to collect them all.

During his sixty-odd years as a painter Francis Bacon fearlessly tackled the unruly imagery of life, remaining defiantly committed to giving "this purposeless existence a meaning." His insistence on depicting the mysteries of human experience had been rare in an age dominated by abstraction. Now, with the international resurgence of figurative imagery, the pivotal importance of his work has become more obvious than ever before.

The power and magnitude of his life's work are vividly conveyed by this thorough evaluation written by Hugh Davies and Sally Yard. Born in Dublin, as a teenager Bacon moved to London, where he worked as an interior designer and taught himself to paint. Responding to influences as diverse as Michelangelo and the photographer Muybridge, he has created a motion-filled style uniquely his own. Fascinated by the challenge of capturing what he calls "the mysteries of appearance," Bacon confronts us with emotional images that demand an emotional response.

About Abbeville's Modern Masters series:

With informative, enjoyable texts and over 100 illustrations—approximately 48 in full color—this innovative series offers a fresh look at the most creative and influential artists of the postwar era. The authors are highly respected art historians and critics chosen for their ability to think clearly and write well. Each handsomely designed volume presents a thorough survey of the artists life and work, as well as statements by the artist, an illustrated chapter on technique, a chronology, lists of exhibitions and public collections, an annotated bibliography, and an index. Every art lover, from the casual museum goer to the serious student, teacher, critic, or curator, will be eager to collect these Modern Masters. And with such a low price, they can afford to collect them all.

Preț: 101.33 lei

Preț vechi: 125.63 lei

-19% Nou

Puncte Express: 152

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.39€ • 20.17$ • 16.01£

19.39€ • 20.17$ • 16.01£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781558592452

ISBN-10: 1558592458

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 218 x 282 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.67 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Modern Masters Series

ISBN-10: 1558592458

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 218 x 282 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.67 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Modern Masters Series

Cuprins

Table of Contents from: Francis Bacon

Introduction

Images after Art

Images from Life

Images of Mortality

Artists Statements

Notes on Technique

Chronology

Exhibitions

Public Collections

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Images after Art

Images from Life

Images of Mortality

Artists Statements

Notes on Technique

Chronology

Exhibitions

Public Collections

Selected Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

Praise for Abbeville's Modern Masters series:

"Each author has thoroughly done his or her homework, knows the historical, critical and personal contexts intimately, and writes extraordinarily well." — Artnews

"Concise, well-produced, and well-written." — New York Times Book Review

"Brief, affordable, well illustrated, and packed with information." — Art in America

"Each author has thoroughly done his or her homework, knows the historical, critical and personal contexts intimately, and writes extraordinarily well." — Artnews

"Concise, well-produced, and well-written." — New York Times Book Review

"Brief, affordable, well illustrated, and packed with information." — Art in America

Notă biografică

Hugh Davies and Sally Yard, both of whom have doctorates in art history from Princeton University, live in La Jolla, California, where Dr. Davies is director of the Museum of Contemporary Art. They have both published extensively on modern art, particularly of the postwar period.

Extras

Excerpt from: Francis Bacon

Introduction

Francis Bacon has steadfastly focused on figurative subject matter throughout his career. Dissatisfied with abstractions lack of human content, he has distorted the inhabitants of his painterly world in order to "unlock the valves of feeling and therefore return the onlooker to life more violently." The murky settings that engulfed his figures for more than a decade after World War II were banished by the brightly illuminated clarity of subsequent work, but the contours that described the figures remained tortuous as the blurring of earlier images gave way to the smearing of paint in later ones: "The mystery lies in the irrationality by which you make appearance—if it is not irrational, you make illustration."

While the vigor of Bacon's paintings parallels that of the Abstract Expressionism of the late 1940s and early 50s, his work has nonetheless remained firmly based in the figuration that also sustained the art of Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland. But Moore's benign family groups and the traditional religious imagery of Sutherland's Crucifixions of the immediate postwar period are remote from the raging figures who dominate Bacon's painterly world of those years. And how strident his paintings must have seemed during the 1950s and 60s next to the spare abstractions of Ben Nicholson, the veils of Morris Louis, the geometric permutations of Frank Stella. At a moment when artists such as Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer in America and Richard Long in Britain were moving out-of-doors to create vast environmental works known to most viewers only in photographic documentation, Bacon's work moved inward, probing the private realms of the psyche. In the vehemence of his attack on the human figure Bacon's work aligns with that of the French artist Jean Dubuffet, although Dubuffet's crude surfaces and primitively hewn forms are farm from the sumptuous facture and mesmerizing distortions of Bacon.

Bacon has in fact stayed resolutely aloof from the successive regroupings of recent art, unmoved by the abstraction that became internationally dominant by the close of World War II. While his paintings have consistently referred to contemporary life, he has also consciously rivaled the old masters. Pointing to the gestural, nonrational marks that "coagulate" in Rembrandt's work to convey the "mystery of fact," Bacon observes:

"And abstract expressionism has all been done in Rembrandt's marks. But in Rembrandt it has been done with the added thing that it was an attempt to record a fact and to me therefore must be much more exciting and much more profound. One of the reasons why I don't like abstract painting, or why it doesn't interest me, is that I think painting is a duality, and that abstract painting is an entirely aesthetic thing…There's never any tension in it."

For his subject matter, Bacon has turned to a world in which he sees no inherent nobility or grand design. "I think of life as meaningless; but we give it meaning during our own existence. We create certain attitudes which give it a meaning while we exist, though they in themselves are meaningless, really." Bacon's works are records of his own subjectivity, inflected with what he calls "exhilarated despair." Yet throughout Bacon's oeuvre there has also been a recollection of myth. He has returned several times to the themes of the Crucifixion and the fate of Prometheus, and he has repeatedly invoked the Furies of Aeschyluss Oresteia. But his is a modern outlook, formed at a time when the ancient dramas of Oedipus and Orestes have assumed fresh pertinence in light of Freudian theories. The Furies have haunted Bacon's work since their appearance in Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944); they reappeared thirty years later in Seated Figure, calling to mind the Eumenides who pursue Harry to Wishwood in The Family Reunion (1939), Bacon's favorite T. S. Eliot play. Harry echoes the cry of Orestes, which had served as an epigraph for Eliot's earlier "Sweeney Agonistes:" "You don't see them, you don't—but I see them: they are hunting me down, I must move on." The themes of pursuit and of the predatory observer became central to Bacon's work from the 1960s onward, as figures poised at doorways look back uneasily and voyeurs intrude into the bedrooms of embracing couples.

In seeking to trap the likeness of life Bacon has been receptive to the promptings of chance. "I think that accident, which I would call luck, is one of the most important and fertile aspects of it.…" But the artists mediation is crucial. "It's really a continuous question of the fight between accident and criticism. Because what I call accident may give you some mark that seems to be more real, truer to the image than another one, but its only your critical sense that can select it." Bacon has cultivated the potent collisions of imagery that he had encountered early on in Surrealism and, perhaps more important, in the tragedies of Aeschylus. He continues to be fascinated by William Bedell Stanford's book Aeschylus in His Style, with its vivid translations of such synaesthetic metaphors as "the reek of human blood smiles out at me."

If Bacon has remained committed to exploring the dark corners of human existence, he has never been interested in straight realism and has stayed far from the Superrealist and Photorealist tendencies of the 1960s and 70s. Dismissing simple representation as essentially illustrational, Bacon cites van Gogh's declaration that "my great longing is to learn to make those very incorrectnesses, those deviations, remodelings, changes in reality, so that they may become, yes, lies if you like—but truer than the literal truth." Along with a very few other artists—among them Frank Auerbach in England, Leon Golub in America, and Karel Appel in Holland—Bacon has amplified the expressive resources of figuration. With the resurgence of figurative imagery and the international emergence of Neo-Expressionism during the past decade, the pivotal importance of his work has become emphatically clear. Although Bacon taught only briefly, at the Royal College of Art in London in 1950, his influence can be discerned in the work of painters ranging from Richard Hamilton and David Hockney to R. B. Kitaj and Malcolm Morley, and his art has commanded the attention of such contemporaries as Willem de Kooning. The fragmented figures of Hockney's recent work, pieced together from multiple photographs, mirror strikingly the dislocations of Bacon's work. Bacon's importance has also extended to such filmmakers as Bernardo Bertolucci, which is especially appropriate since photography and film have proved so inspirational to the artist: "I think ones sense of appearance is assaulted all the time by photography and by the film…I've always been haunted by them…I think it's the slight remove from fact, which returns me onto the fact more violently." The spaces and action of Last Tango in Paris owe much to Bacon's art, an allusion acknowledged by Bertolucci in his use of two of Bacon's paintings during the opening credits.

That Bacon's work has been a force unto itself for nearly half a century has not deterred museums and galleries from lavishing attention on him. Major retrospectives assembled by the Tate Gallery in 1962 and the Guggenheim Museum in 1963 confirmed his position in Europe and America. Important exhibitions of his paintings in Paris, Düsseldorf, and New York during the 1970s were timely, as such artists as Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Jörg Immendorff in Germany; Sandro Chia and Francesco Clemente in Italy; and Eric Fischl, Susan Rothenberg, and David Salle in America were challenging the twenty-year hegemony of nonobjective art with bold figurative images. In 1985, after nearly a quarter of a century, the Tate Gallery organized a second major retrospective.

From a distance of forty years, Bacon's clamorous appearance on the London art scene in the 1940s seems a crucial moment in modern art. As artists in England sought to restore the wholeness of humanity and painters in America pressed toward increasing abstraction, Bacon aggressively confronted the blunt realities of existence. Nearly two decades would elapse before the figure would regain a central position in Western art and before such dissimilar German artists as Immendorff and Joseph Beuys would take as their subject the human evil revealed during the first half of our century. By then the magisterial thugs of Bacon's earlier paintings had been supplanted by the friends who haunt the more recent work. Tackling the unruly imagery of life, Bacon has been guided by mentors past and present. Alerted by Freud and the Surrealists to the startling insights of the subconscious and impressed by the blunt potency of news photographs, he has been no less dazzled by the formal rhythms of the art of earlier centuries.

Introduction

Francis Bacon has steadfastly focused on figurative subject matter throughout his career. Dissatisfied with abstractions lack of human content, he has distorted the inhabitants of his painterly world in order to "unlock the valves of feeling and therefore return the onlooker to life more violently." The murky settings that engulfed his figures for more than a decade after World War II were banished by the brightly illuminated clarity of subsequent work, but the contours that described the figures remained tortuous as the blurring of earlier images gave way to the smearing of paint in later ones: "The mystery lies in the irrationality by which you make appearance—if it is not irrational, you make illustration."

While the vigor of Bacon's paintings parallels that of the Abstract Expressionism of the late 1940s and early 50s, his work has nonetheless remained firmly based in the figuration that also sustained the art of Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland. But Moore's benign family groups and the traditional religious imagery of Sutherland's Crucifixions of the immediate postwar period are remote from the raging figures who dominate Bacon's painterly world of those years. And how strident his paintings must have seemed during the 1950s and 60s next to the spare abstractions of Ben Nicholson, the veils of Morris Louis, the geometric permutations of Frank Stella. At a moment when artists such as Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer in America and Richard Long in Britain were moving out-of-doors to create vast environmental works known to most viewers only in photographic documentation, Bacon's work moved inward, probing the private realms of the psyche. In the vehemence of his attack on the human figure Bacon's work aligns with that of the French artist Jean Dubuffet, although Dubuffet's crude surfaces and primitively hewn forms are farm from the sumptuous facture and mesmerizing distortions of Bacon.

Bacon has in fact stayed resolutely aloof from the successive regroupings of recent art, unmoved by the abstraction that became internationally dominant by the close of World War II. While his paintings have consistently referred to contemporary life, he has also consciously rivaled the old masters. Pointing to the gestural, nonrational marks that "coagulate" in Rembrandt's work to convey the "mystery of fact," Bacon observes:

"And abstract expressionism has all been done in Rembrandt's marks. But in Rembrandt it has been done with the added thing that it was an attempt to record a fact and to me therefore must be much more exciting and much more profound. One of the reasons why I don't like abstract painting, or why it doesn't interest me, is that I think painting is a duality, and that abstract painting is an entirely aesthetic thing…There's never any tension in it."

For his subject matter, Bacon has turned to a world in which he sees no inherent nobility or grand design. "I think of life as meaningless; but we give it meaning during our own existence. We create certain attitudes which give it a meaning while we exist, though they in themselves are meaningless, really." Bacon's works are records of his own subjectivity, inflected with what he calls "exhilarated despair." Yet throughout Bacon's oeuvre there has also been a recollection of myth. He has returned several times to the themes of the Crucifixion and the fate of Prometheus, and he has repeatedly invoked the Furies of Aeschyluss Oresteia. But his is a modern outlook, formed at a time when the ancient dramas of Oedipus and Orestes have assumed fresh pertinence in light of Freudian theories. The Furies have haunted Bacon's work since their appearance in Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944); they reappeared thirty years later in Seated Figure, calling to mind the Eumenides who pursue Harry to Wishwood in The Family Reunion (1939), Bacon's favorite T. S. Eliot play. Harry echoes the cry of Orestes, which had served as an epigraph for Eliot's earlier "Sweeney Agonistes:" "You don't see them, you don't—but I see them: they are hunting me down, I must move on." The themes of pursuit and of the predatory observer became central to Bacon's work from the 1960s onward, as figures poised at doorways look back uneasily and voyeurs intrude into the bedrooms of embracing couples.

In seeking to trap the likeness of life Bacon has been receptive to the promptings of chance. "I think that accident, which I would call luck, is one of the most important and fertile aspects of it.…" But the artists mediation is crucial. "It's really a continuous question of the fight between accident and criticism. Because what I call accident may give you some mark that seems to be more real, truer to the image than another one, but its only your critical sense that can select it." Bacon has cultivated the potent collisions of imagery that he had encountered early on in Surrealism and, perhaps more important, in the tragedies of Aeschylus. He continues to be fascinated by William Bedell Stanford's book Aeschylus in His Style, with its vivid translations of such synaesthetic metaphors as "the reek of human blood smiles out at me."

If Bacon has remained committed to exploring the dark corners of human existence, he has never been interested in straight realism and has stayed far from the Superrealist and Photorealist tendencies of the 1960s and 70s. Dismissing simple representation as essentially illustrational, Bacon cites van Gogh's declaration that "my great longing is to learn to make those very incorrectnesses, those deviations, remodelings, changes in reality, so that they may become, yes, lies if you like—but truer than the literal truth." Along with a very few other artists—among them Frank Auerbach in England, Leon Golub in America, and Karel Appel in Holland—Bacon has amplified the expressive resources of figuration. With the resurgence of figurative imagery and the international emergence of Neo-Expressionism during the past decade, the pivotal importance of his work has become emphatically clear. Although Bacon taught only briefly, at the Royal College of Art in London in 1950, his influence can be discerned in the work of painters ranging from Richard Hamilton and David Hockney to R. B. Kitaj and Malcolm Morley, and his art has commanded the attention of such contemporaries as Willem de Kooning. The fragmented figures of Hockney's recent work, pieced together from multiple photographs, mirror strikingly the dislocations of Bacon's work. Bacon's importance has also extended to such filmmakers as Bernardo Bertolucci, which is especially appropriate since photography and film have proved so inspirational to the artist: "I think ones sense of appearance is assaulted all the time by photography and by the film…I've always been haunted by them…I think it's the slight remove from fact, which returns me onto the fact more violently." The spaces and action of Last Tango in Paris owe much to Bacon's art, an allusion acknowledged by Bertolucci in his use of two of Bacon's paintings during the opening credits.

That Bacon's work has been a force unto itself for nearly half a century has not deterred museums and galleries from lavishing attention on him. Major retrospectives assembled by the Tate Gallery in 1962 and the Guggenheim Museum in 1963 confirmed his position in Europe and America. Important exhibitions of his paintings in Paris, Düsseldorf, and New York during the 1970s were timely, as such artists as Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Jörg Immendorff in Germany; Sandro Chia and Francesco Clemente in Italy; and Eric Fischl, Susan Rothenberg, and David Salle in America were challenging the twenty-year hegemony of nonobjective art with bold figurative images. In 1985, after nearly a quarter of a century, the Tate Gallery organized a second major retrospective.

From a distance of forty years, Bacon's clamorous appearance on the London art scene in the 1940s seems a crucial moment in modern art. As artists in England sought to restore the wholeness of humanity and painters in America pressed toward increasing abstraction, Bacon aggressively confronted the blunt realities of existence. Nearly two decades would elapse before the figure would regain a central position in Western art and before such dissimilar German artists as Immendorff and Joseph Beuys would take as their subject the human evil revealed during the first half of our century. By then the magisterial thugs of Bacon's earlier paintings had been supplanted by the friends who haunt the more recent work. Tackling the unruly imagery of life, Bacon has been guided by mentors past and present. Alerted by Freud and the Surrealists to the startling insights of the subconscious and impressed by the blunt potency of news photographs, he has been no less dazzled by the formal rhythms of the art of earlier centuries.